For many years, the idea that “sleeping on it” would provide an individual with some time in which their subconscious mind would work through a problem or problems has generally been accepted as common sense. This does not mean that the scientific basis for the idea is unknown or unsupported by research.

Recent findings provide experimental evidence that dreaming during REM sleep may serve as an aid for creative problem-solving in the subsequent hours or days following dreaming.

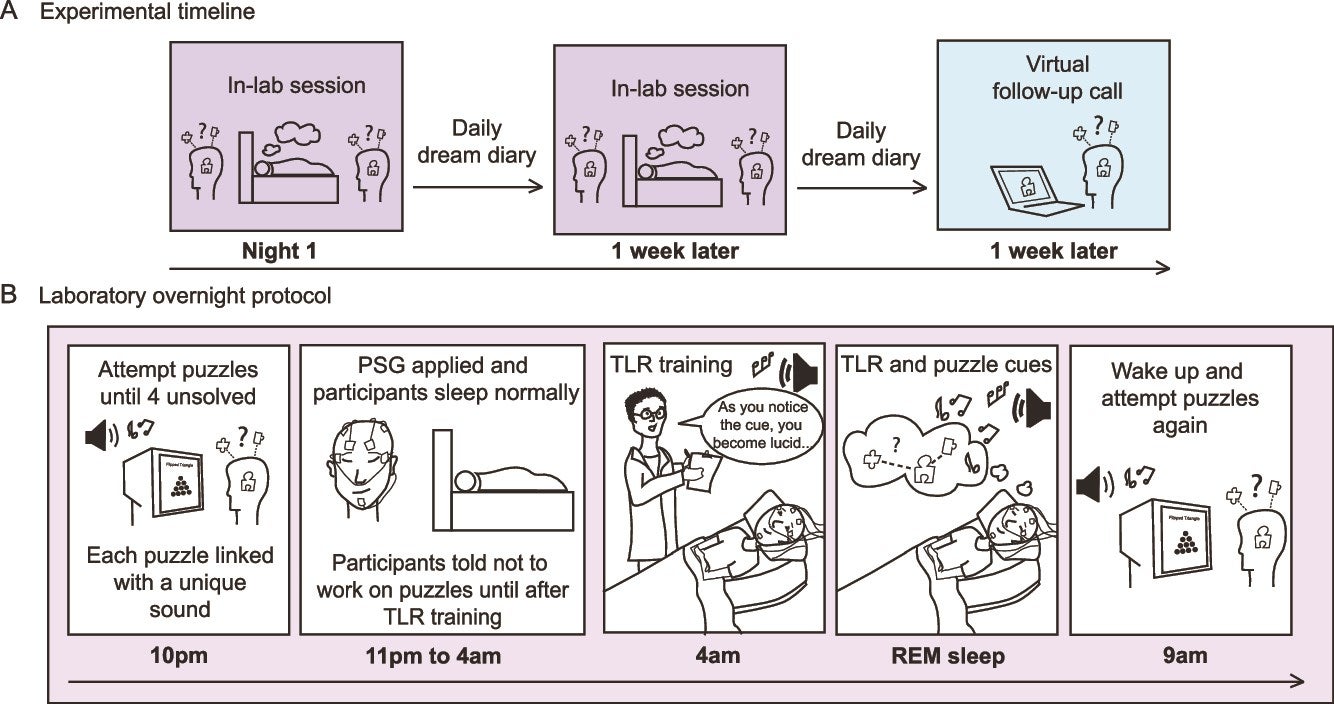

Using a method known as targeted memory reactivation, this study tested whether dreaming caused participants’ increased ability to solve puzzles, or whether dreaming simply reflected previously processed and tangible memories in the brain. The study was conducted by a team of neuroscientists at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, led by Karen Konkoly, the lead author on the paper, along with Ken Paller, James Padilla Professor of Psychology and Director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Program at Northwestern.

The findings were published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, which is a rarity for experimental data supporting the concept of dream “guidance” and bolstered creativity. As a result, the study furthered understanding of how dreams work while also providing additional insight into the importance of dreams as a cogent part of an individual’s cognitive processes.

For decades, scientists have established that sleep plays a beneficial role in memory and learning. However, demonstrating that dreams themselves play an integral role in solving problems has proven to be extremely daunting. The dream state is often viewed as unpredictable and difficult to control.

The current study attempted to overcome this obstacle by using targeted memory reactivation. In this approach, very low-volume audio cues were presented during sleep in order to gently nudge the brain toward specific memories.

Researchers involved in this study recruited 20 participants who had experience with lucid dreaming. This ability allowed participants to occasionally recognize that they were dreaming while still asleep. When placed in a laboratory setting, all participants were asked to attempt to solve a series of brain teaser puzzles, with a maximum of three minutes allowed for each puzzle-solving attempt.

Each puzzle had its own specific soundtrack. However, the vast majority of puzzles remained unsolved. Participants then spent the night in the laboratory while their brain activity was monitored by researchers.

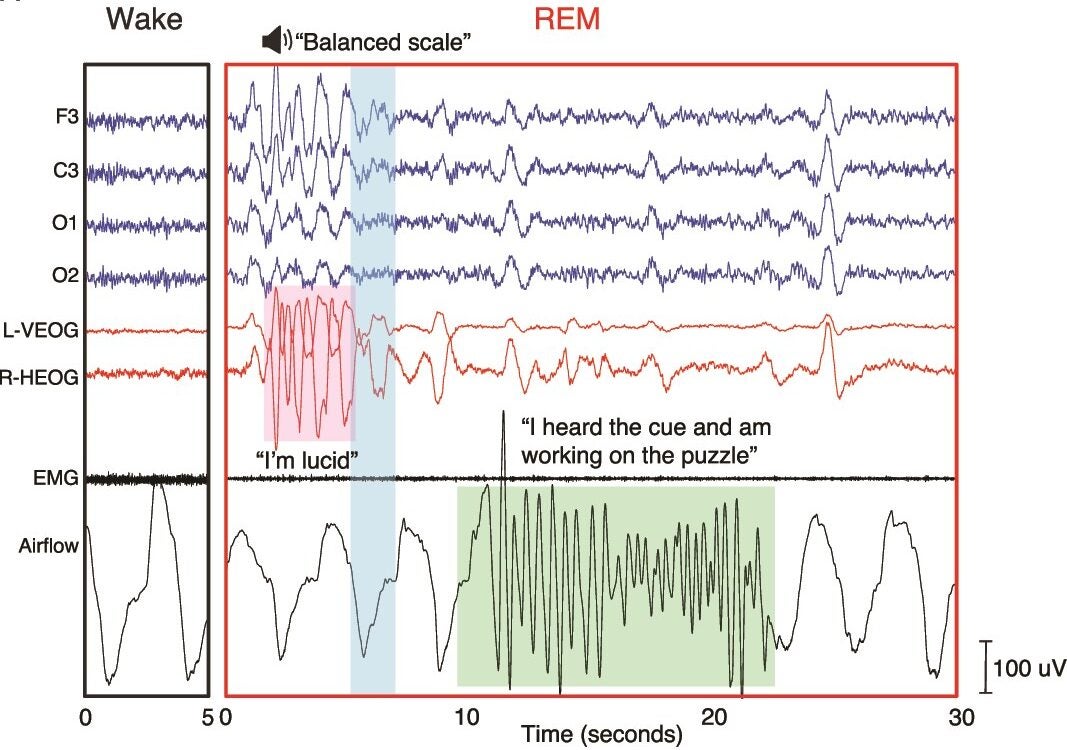

During REM sleep, when researchers confirmed through electrical brain signals that participants were asleep, the soundtracks associated with half of the unsolved puzzles were played back. REM sleep is the phase in which the brain generates vivid and complex dreams.

Some participants used pre-arranged signals, specifically a distinctive pattern of sniffing, to indicate when they had heard the sound and were actively thinking about the connected puzzle within a dream. Upon awakening, all participants provided detailed oral descriptions of their dreams.

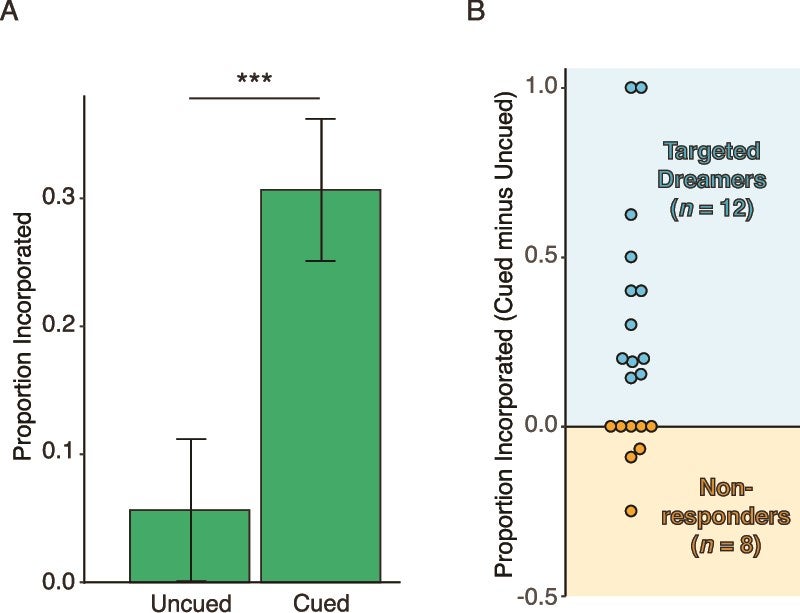

Findings from the study were unexpected. Approximately 75 percent of participants reported dream content connected with the unsolved puzzles. Twelve of the twenty participants described dream content that directly referenced puzzles that had been cued with sound, compared with puzzles that had not been cued.

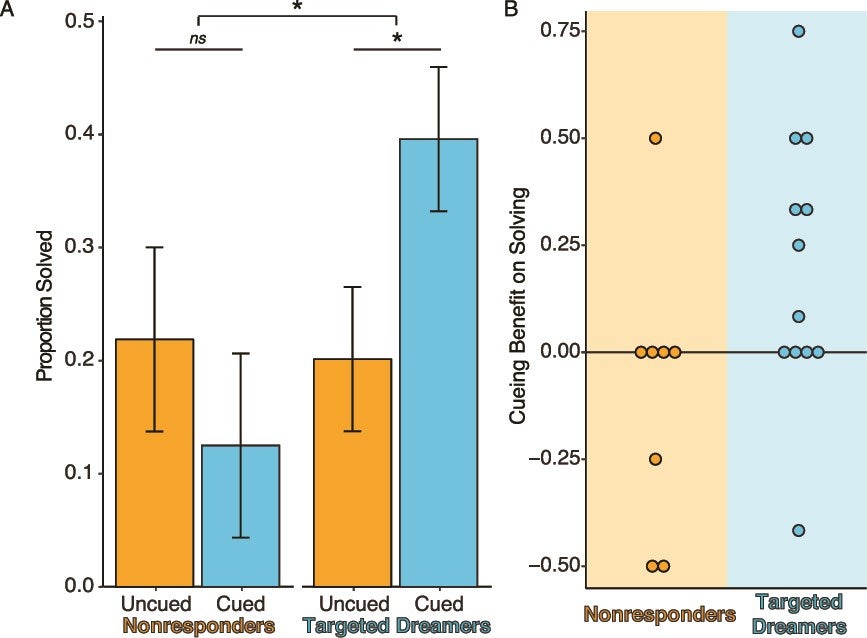

Participants whose dreams showed a response to the sound cues experienced an approximate doubling of problem-solving success. Success rates increased from about 20 percent to 40 percent after waking. The dream content appeared to influence creative problem-solving improvement.

However, there was no evidence from the study to suggest that the dreams themselves directly caused the solutions. Other variables, such as curiosity and motivation, may influence both the quality of dreams and the ability to guide dream themes or content. Still, the ability to direct a person’s dreams in any capacity represents an important milestone in investigating the relationship between sleep, dreaming, and creative problem-solving.

Konkoly noted that she was particularly surprised by how frequently participants responded to auditory stimuli within non-lucid dreams. She illustrated this by explaining that one participant asked a character in their dream for assistance in solving a puzzle that had been presented as an audio cue.

In another example, a participant was given a tree-related puzzle via an audio cue and later dreamt of walking through a forest. Other instances included participants who were cued with a jungle puzzle and subsequently dreamt of fishing in a jungle environment.

These examples suggest that the subconscious mind may adhere to instructions delivered through auditory stimuli, even when the individual is not consciously alert. Interestingly, puzzles introduced through non-lucid dream experiences were solved more frequently than those introduced during lucid dreaming.

This finding indicates that the brain’s natural, unconscious approach may provide more benefit than deliberate, effortful thinking while awake.

Creative approaches often require a break from standard logical reasoning, a phenomenon psychologists refer to as incubation. During dreaming, particularly in the rapid eye movement stage of sleep, the brain appears capable of forming loose or non-linear associations and producing ideas linked through memory rather than direct logical connections.

Previous studies have suggested that REM sleep allows the brain to remap distant or less familiar associations in ways that help overcome obstacles. The current research supports this idea. Viewing a problem from a different angle during a dream state may allow thoughts to reorganize in new ways.

This process may ultimately produce useful results for creative problem-solving through dream-based analysis.

“Today’s world requires creative answers to many problems faced by society,” Paller stated. “By continuing to learn how our brains can be creative and provide new solutions to current conditions, we may develop new methods for solving our most urgent challenges, and dream engineering is part of the way we are developing these methods.”

The findings from this research open several avenues for future scientific investigation. Researchers may further explore the role of sleep and dreaming in creativity, learning, and mental and emotional regulation.

In addition, scientists may examine whether the methodologies used to investigate the dream state could also apply to emotional regulation, general learning, and personal decision-making. If future research confirms that dreams can be accessed as a tool for problem-solving, sleep may come to be viewed as more valuable to mental and emotional health than it currently is.

Simple behaviors, such as ensuring sufficient REM sleep or reflecting on a problem before sleep, may eventually be paired with gentle, scientifically developed tools designed to support creativity. Konkoly expressed hope that the study would encourage a shift in how the scientific community views dreams.

“If scientists can demonstrate to theorists that dreams are instrumental in developing solutions to puzzles, creativity, and enhancing emotional regulation,” she said, “then the profession will likely view dreams as an essential priority in developing mental health and emotional wellbeing.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Neuroscience of Consciousness.

The original story “Guided dreams during REM sleep can boost problem solving” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Guided dreams during REM sleep can boost problem solving appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.