At the University of Sydney, a Ph.D. student has recreated a tiny slice of outer space and used it to make cosmic dust from scratch.

Linda Losurdo, a doctoral researcher in materials and plasma physics at the University of Sydney School of Physics, led the work alongside her supervisor, Professor David McKenzie. Their findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal, show how the chemical building blocks of life may have formed long before Earth even existed.

The experiment starts with a simple setup. A mix of common gases, including nitrogen and carbon-based compounds, is sealed inside glass tubes. When high electrical energy is applied, the gases break apart and recombine under harsh conditions that resemble space environments around stars and stellar explosions.

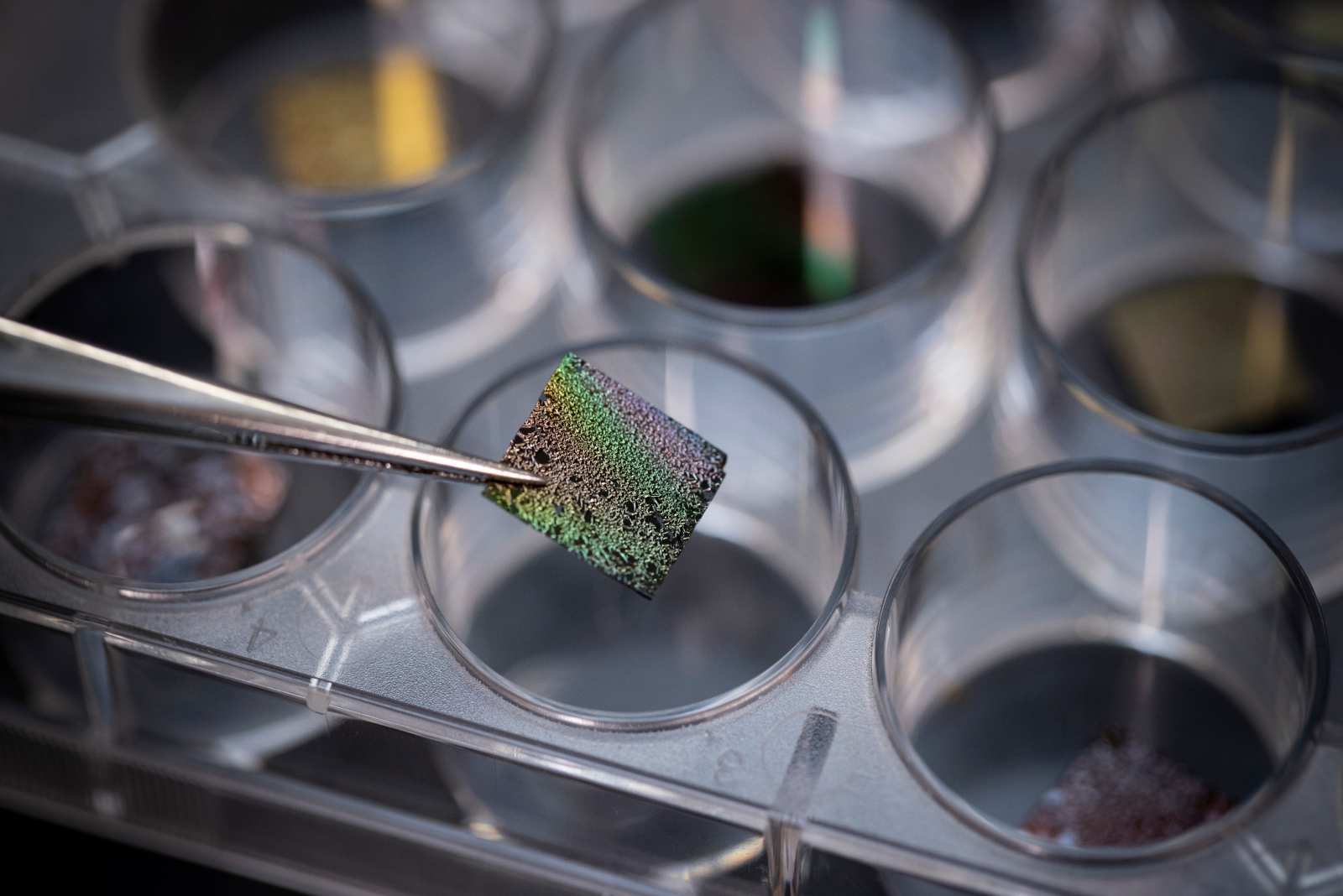

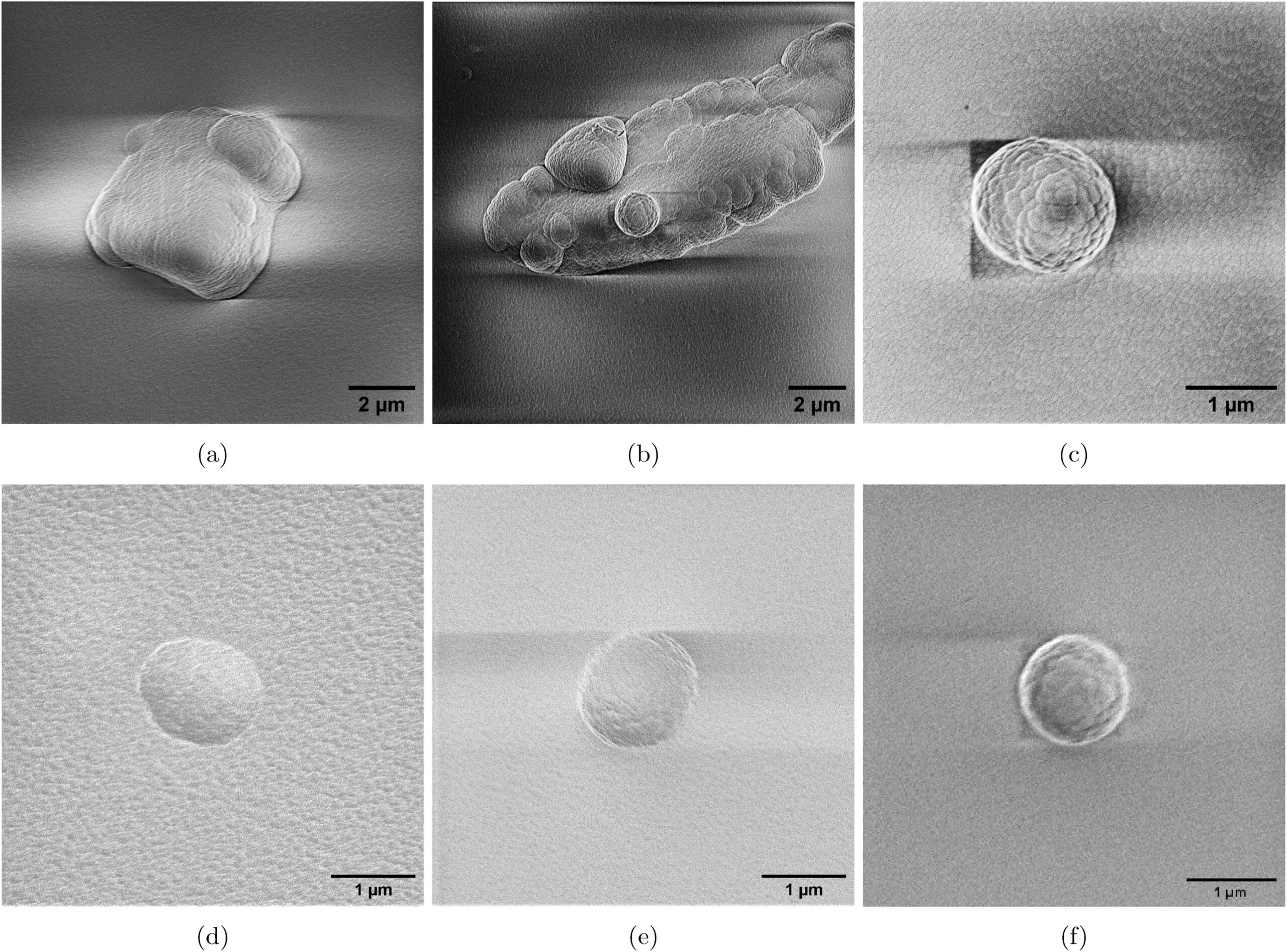

Over time, tiny particles form and settle onto small surfaces inside the tube. What you get is carbon-rich cosmic dust, the same kind of material that drifts between stars and later ends up inside comets, asteroids, and meteorites.

The dust contains carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, known together as CHON elements. These elements are central to many organic molecules linked to life.

“We no longer have to wait for an asteroid or comet to come to Earth to understand their histories,” Losurdo said. “You can build analog environments in the laboratory and reverse engineer their structure using infrared fingerprints.”

Those fingerprints are key. Cosmic dust glows in infrared light in ways that reveal its chemical makeup. When the team measured the dust created in the lab, its infrared signal closely matched what astronomers detect in space. That confirmed the process realistically mirrors how cosmic dust forms beyond Earth.

Cosmic dust may look insignificant, but it plays a major role in the story of life. Scientists have long debated where Earth’s earliest organic molecules came from. Some may have formed on the young planet itself. Others likely arrived from space.

Billions of years ago, Earth was bombarded by meteorites, micrometeorites, and fine dust from comets and asteroids. Many of those objects carried complex organic material. What remained unclear was how that material formed in the first place.

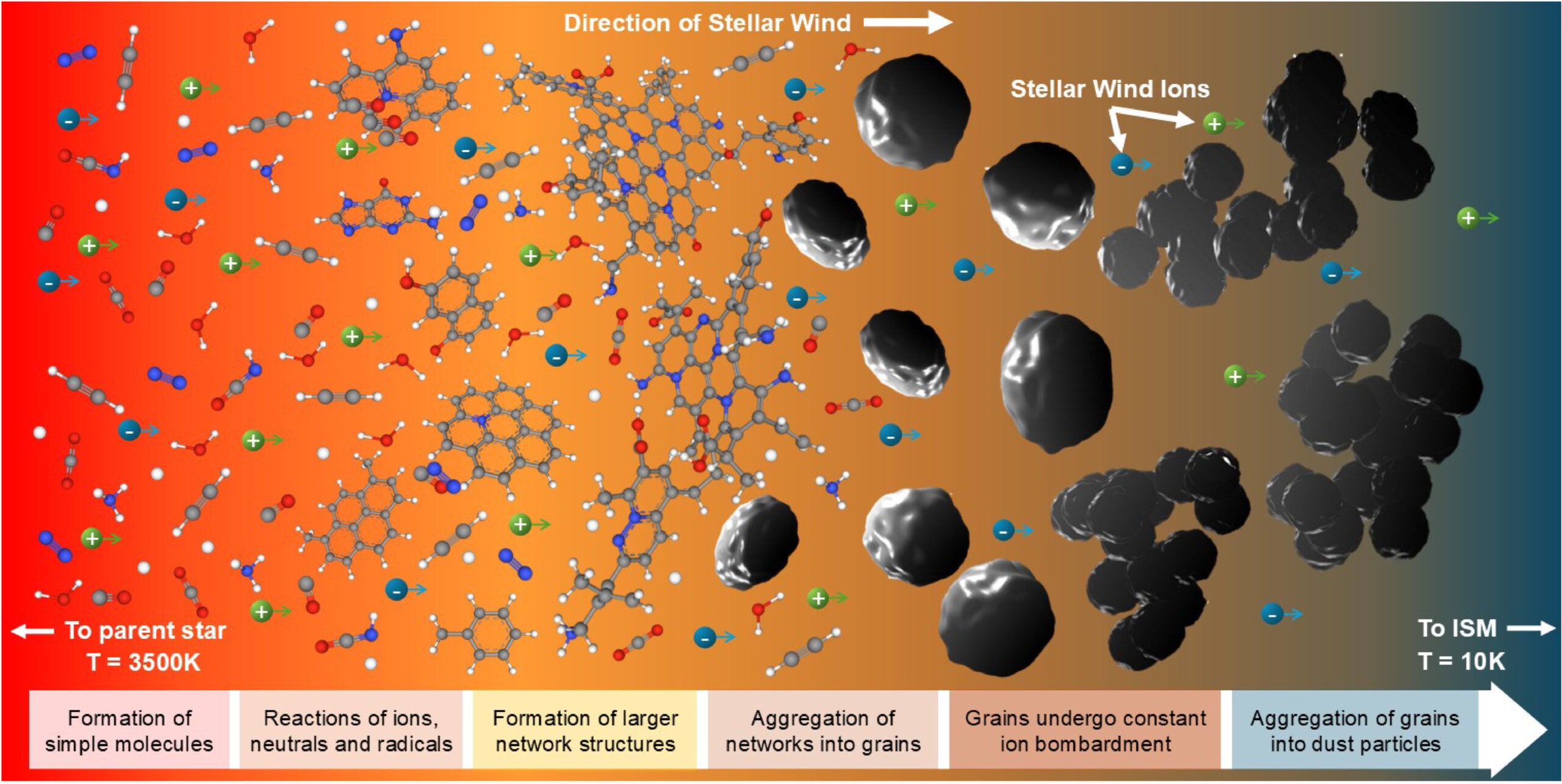

“Covalently bonded carbon and hydrogen in comet and asteroid material are believed to have formed in the outer envelopes of stars, in high-energy events like supernovae, and in interstellar environments,” Losurdo said.

The lab work helps fill in that missing chapter. By recreating space-like conditions, the researchers can test how simple molecules grow into more complex networks that survive long journeys through space.

Cosmic dust does not form in calm settings. In space, particles are constantly hit by charged particles and exposed to radiation and heat. Each of those experiences leaves a chemical mark.

In the lab, the Sydney team focused on two major influences: energetic impacts during formation and heating that occurs later. By controlling these factors separately, they were able to see how each one changes the dust’s structure.

Professor McKenzie said this approach opens new doors for space science.

“By making cosmic dust in the lab, we can explore the intensity of ion impacts and temperatures involved when dust forms in space,” he said. “That’s important if you want to understand the environments inside cosmic dust clouds, where life-relevant chemistry is thought to be happening.”

He added that these experiments also help scientists read the history stored inside meteorites and asteroid fragments.

“Its chemical signature holds a record of its journey, and experiments like this help us learn how to read that record,” McKenzie said.

One of the study’s long-term goals is to help astronomers interpret observations from powerful space telescopes. Instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope can detect infrared signals from distant dust clouds, but those signals are only useful if scientists know how to decode them.

By building a reference library of lab-made cosmic dust, researchers can compare telescope data to known chemical patterns. That makes it easier to identify regions in space where complex organic chemistry is active.

The work also supports future missions that return samples from asteroids and comets. When scientists examine those materials on Earth, they can compare them to lab-created dust to better understand what they experienced in space.

Research findings are available online in the Astrophysical Journal.

The original story “Student made cosmic dust in the lab revealing life’s early chemical origins” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Student made cosmic dust in the lab revealing life’s early chemical origins appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.