Mass General Brigham researchers are betting that the next big leap in brain medicine will come from teaching artificial intelligence to “read” MRI scans in a more flexible way.

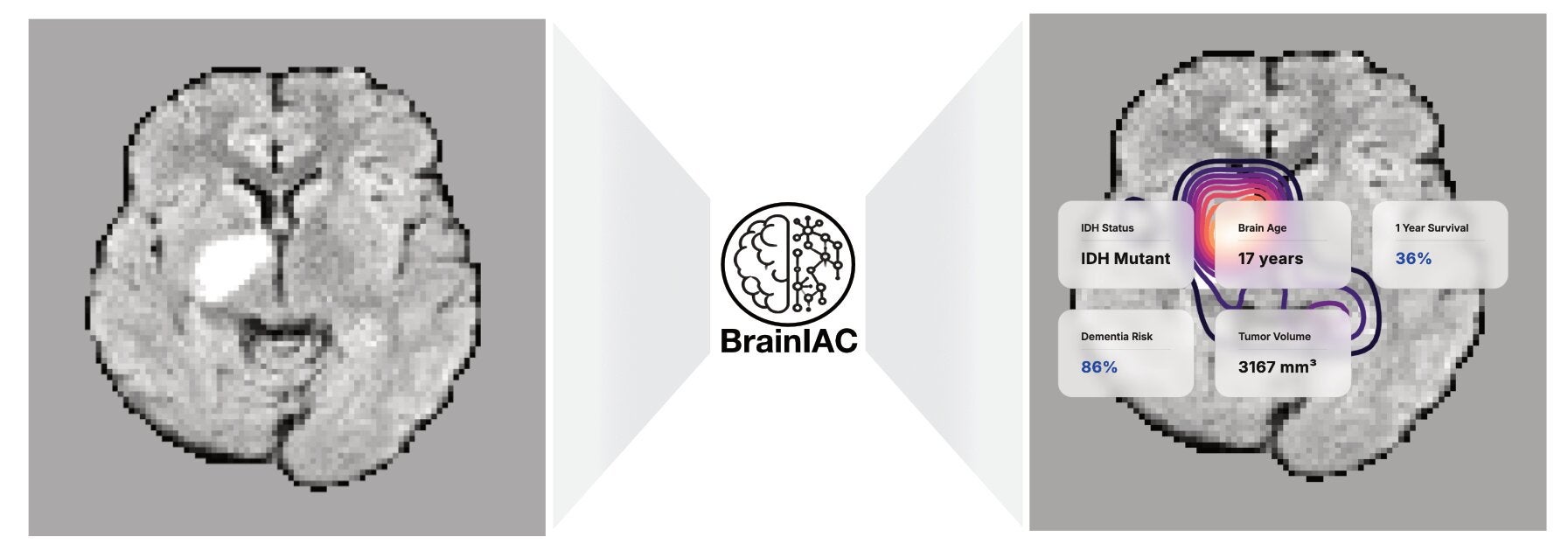

The team, led by Benjamin Kann, MD, in the Artificial Intelligence in Medicine (AIM) Program at Mass General Brigham, built a new AI foundation model called BrainIAC. In a study published in Nature Neuroscience, the model handled many brain MRI jobs at once, from estimating brain age to predicting dementia risk. It also looked for tumor gene changes and helped forecast survival in brain cancer.

“BrainIAC has the potential to accelerate biomarker discovery, enhance diagnostic tools and speed the adoption of AI in clinical practice,” Kann said. “Integrating BrainIAC into imaging protocols could help clinicians better personalize and improve patient care.”

If you follow medical AI news, you have seen a pattern. Many models do one thing well, then struggle outside their home hospital. Brain MRI makes that problem worse. Scans can look different across institutions, scanner brands, and settings. Even the same patient can have several MRI “sequences,” each showing tissue in a different way.

Common sequences include T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR, and T1-weighted with contrast enhancement (T1CE). Hospitals do not always collect the same set. Scanner strength can vary from 1.5T to 7T. Imaging settings also shift brightness and contrast. That mix can confuse models trained on narrow, labeled datasets.

You also run into a basic bottleneck. Many AI systems need lots of labeled images, meaning experts must mark findings by hand. For rare diseases or specialized scans, those labels can be hard to get.

To get around that, the Mass General Brigham team designed BrainIAC as a general-purpose “encoder” for full 3D MRI volumes. Instead of learning mainly from labeled examples, it used self-supervised learning. That method lets the model learn patterns from scans without annotations.

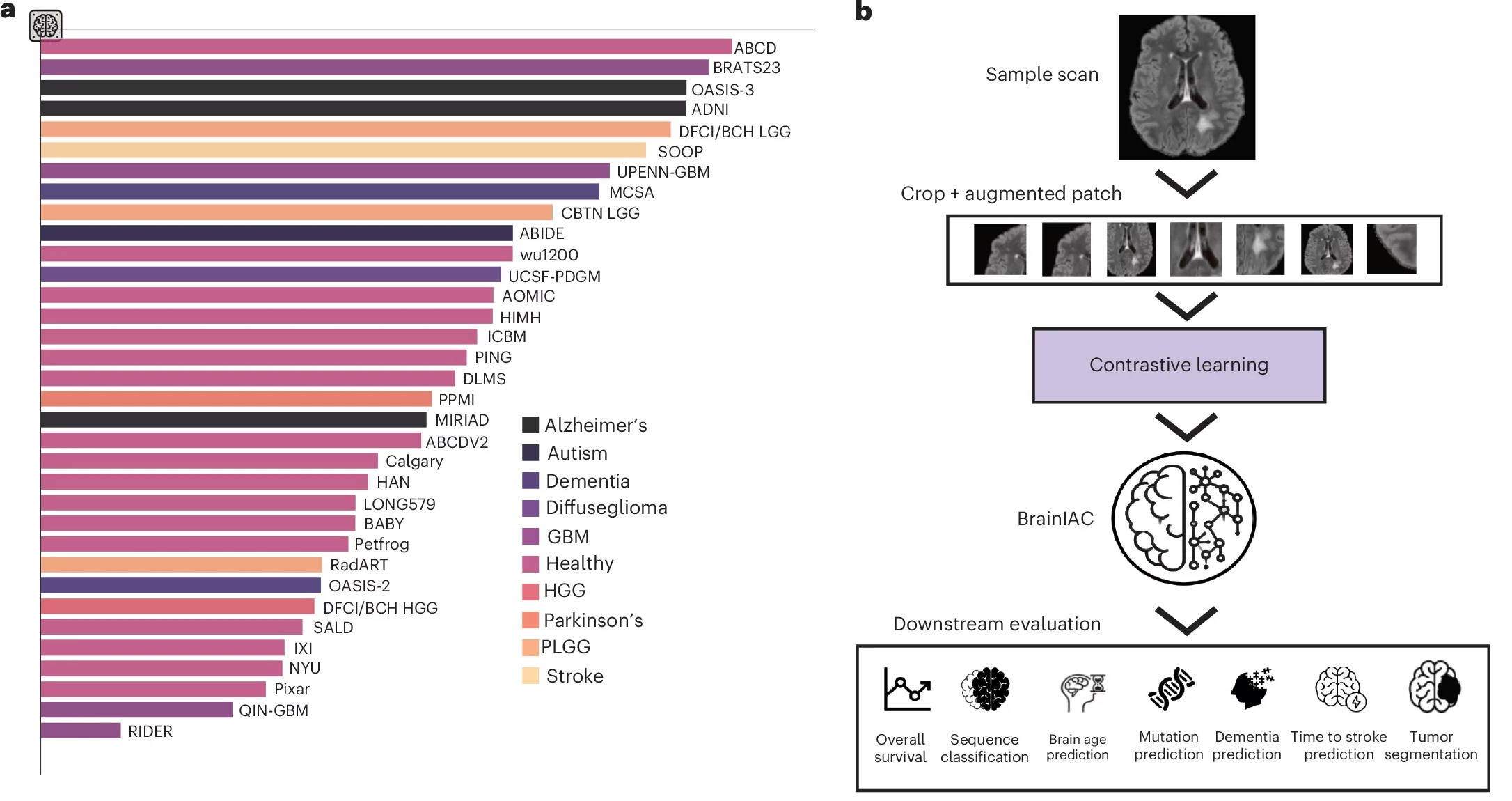

BrainIAC was pretrained on 32,015 multiparametric MRIs pulled from 16 datasets that covered 10 medical conditions. Across the full set of experiments, the researchers curated 48,965 scans from 34 datasets.

The pretraining approach was based on SimCLR, a contrastive learning method. The model saw many cropped patches from 3D scans. It learned to treat two altered views of the same brain region as related. It also learned that different patches should look less related in its internal “map” of features.

The researchers tested three options for the model’s backbone and chose SimCLR-ViT-B. That version performed most consistently when the team gave it only a few labeled examples.

After pretraining, the team evaluated BrainIAC on seven tasks that range from simple sorting to hard clinical prediction. Those tasks included MRI sequence classification, brain age prediction, early dementia prediction, time-to-stroke prediction, IDH mutation status prediction in glioma, survival prediction for glioblastoma, and adult glioma tumor segmentation.

They compared BrainIAC with three baselines. One model trained from scratch. Another used transfer learning from MedicalNet, a 3D medical imaging pretrained model. A third was a segmentation-focused foundation model called BrainSegFounder.

In MRI sequence classification, BrainIAC stood out when training data was limited. Using the BraTS 2023 dataset, BrainIAC hit 90.8% balanced accuracy with only 10% of the training data. With more data, it rose to 97.2%.

For brain age prediction, the team used 6,249 T1-weighted scans and measured error in years. On an external test set with 20% training availability, BrainIAC reached a mean absolute error of 6.55 years. Other models posted larger errors.

Some of the hardest tasks involve information you cannot easily spot on a scan. One example is predicting IDH mutation status in low-grade glioma. That gene change can shape treatment plans and outcomes. With just 10% training availability, BrainIAC reached an AUC of 0.68. With full training data, it reached 0.79.

The team also tested survival prediction for glioblastoma, using the UPENN-GBM dataset. The target was survival at one year post-treatment. At 10% training availability, BrainIAC reached an AUC of 0.62 and outperformed the comparison models. With full training data, it reached 0.72. The researchers also split patients into high- and low-risk groups. They reported significant separation in survival curves in several settings.

BrainIAC also performed well on early dementia-related prediction. Using OASIS-1, the task was mild cognitive impairment (MCI) versus healthy control classification. With full training data, BrainIAC reached an AUC of 0.88.

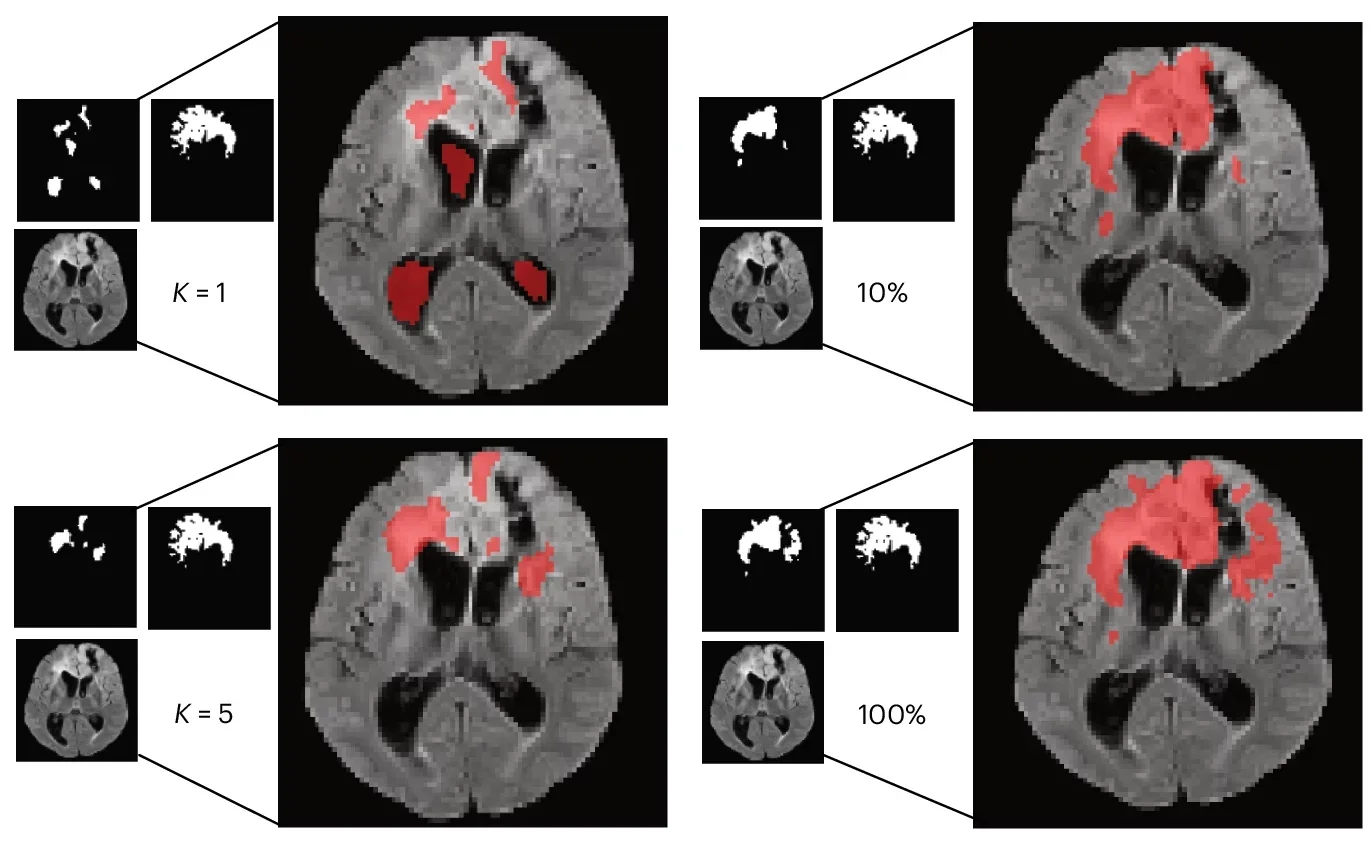

Real clinics do not always have big, labeled datasets waiting for a model. So the team ran few-shot tests. In these trials, the model learned from K = 1 or K = 5 labeled examples per class.

BrainIAC generally held up better than the alternatives. In sequence classification with K = 1, it reached 0.53 balanced accuracy. In IDH mutation prediction with K = 1, it reached an AUC of 0.64. In tumor segmentation, it reached a Dice score of 0.51 with only one sample.

The researchers also ran “linear probing,” where the core BrainIAC encoder stays frozen and only a small task head is trained. Across all seven tasks, the frozen BrainIAC features still supported strong results, which suggests the model learned broadly useful patterns.

The team tested robustness too. They added synthetic changes meant to mimic real MRI issues, like contrast shifts and imaging artifacts. BrainIAC stayed more stable than the other models, especially in low-data settings.

The researchers say the model still has limits. It focuses on standard structural sequences, including T1w, T2w, FLAIR, and T1CE. It did not include diffusion-weighted imaging or functional MRI. It also used skull-stripped images, which narrows use to intracranial analysis. The team says larger datasets and more imaging types could push performance further.

If BrainIAC or similar models move into wider testing, you could see faster progress in brain biomarkers, the measurable signs of disease that help guide care. A foundation model that works with fewer labels could help hospitals build tools even when expert annotations are scarce.

You could also see more consistent AI performance across sites. BrainIAC was designed to handle the messy reality of MRI variation. That may help reduce the gap between lab demos and real clinic use.

For patients, better prediction tools could support earlier risk estimates for dementia, sharper planning for brain cancer care, and stronger guidance when time matters, like after a stroke. For researchers, a reusable brain MRI model could speed studies by cutting the time needed to build new systems from scratch.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The original story “Brain MRIs and AI predict brain age, cancer survival, and other diseases” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Brain MRIs and AI predict brain age, cancer survival, and other diseases appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.