Penn State researchers think a key ingredient for life may have formed in deep freeze, not in a warm asteroid puddle.

Scientists at Penn State; led by geoscientist Allison Baczynski and postdoctoral researcher Ophélie McIntosh; studied amino acids in material from the asteroid Bennu. Their work appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission delivered the Bennu sample to Earth in 2023. Earlier tests found amino acids in that 4.6-billion-year-old dust. Amino acids are the small molecules that join up to make proteins.

The big question has been simple: Where did those amino acids form? Many scientists pictured mild, watery chemistry inside an asteroid. The Penn State team says Bennu’s chemistry points somewhere colder.

“Our results flip the script on how we have typically thought amino acids formed in asteroids,” said Baczynski, an assistant research professor of geosciences at Penn State and co-lead author on the paper. “It now looks like there are many conditions where these building blocks of life can form, not just when there’s warm liquid water. Our analysis showed that there’s much more diversity in the pathways and conditions in which these amino acids can be formed.”

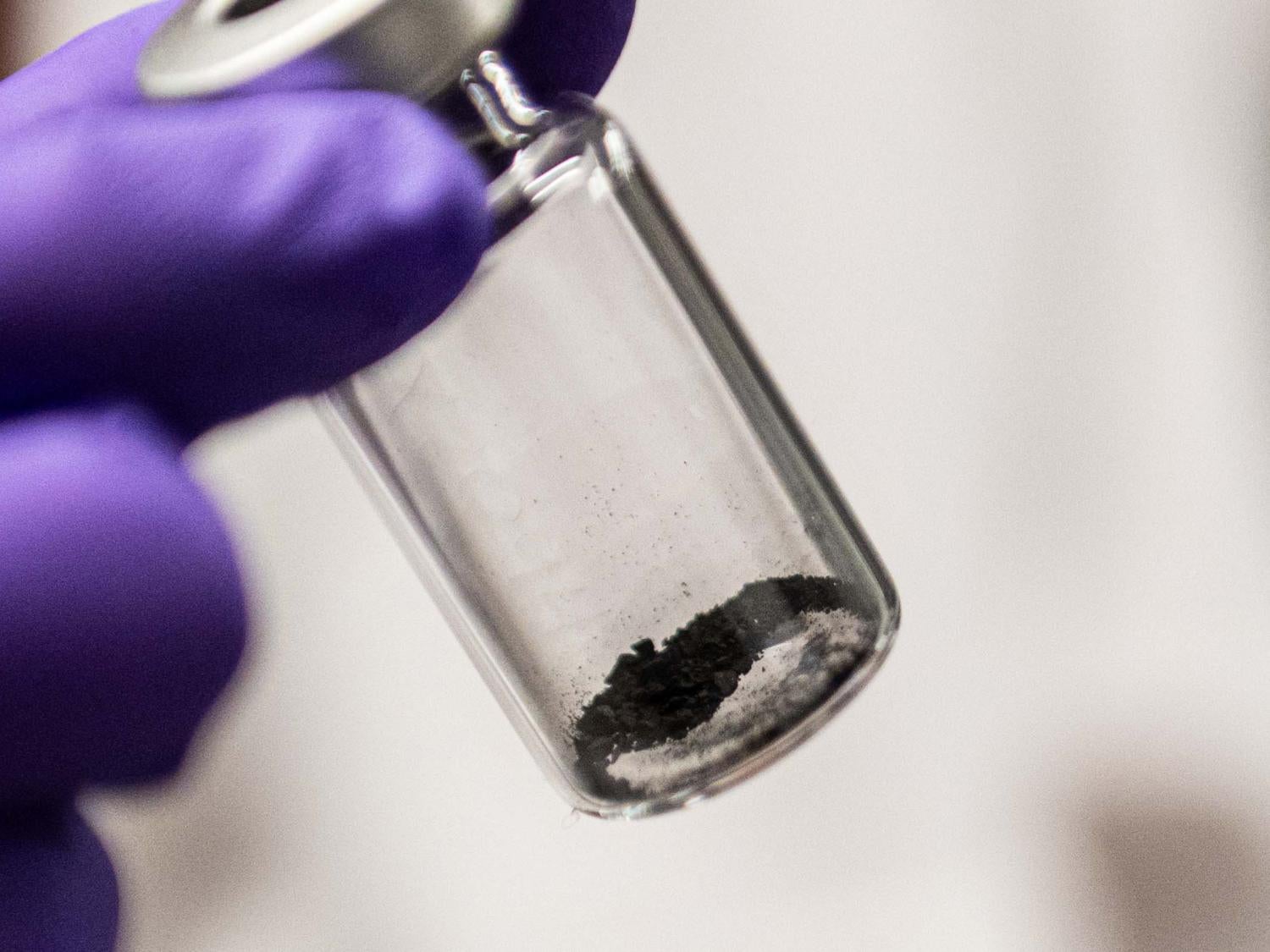

The team worked with a speck of asteroid material, about a teaspoon in size. They measured isotopes; tiny mass differences in atoms that act like chemical fingerprints.

They focused first on glycine, the simplest amino acid. It has just two carbon atoms. Even so, it matters. Glycine is often treated as a sign that early “pre-life” chemistry was happening.

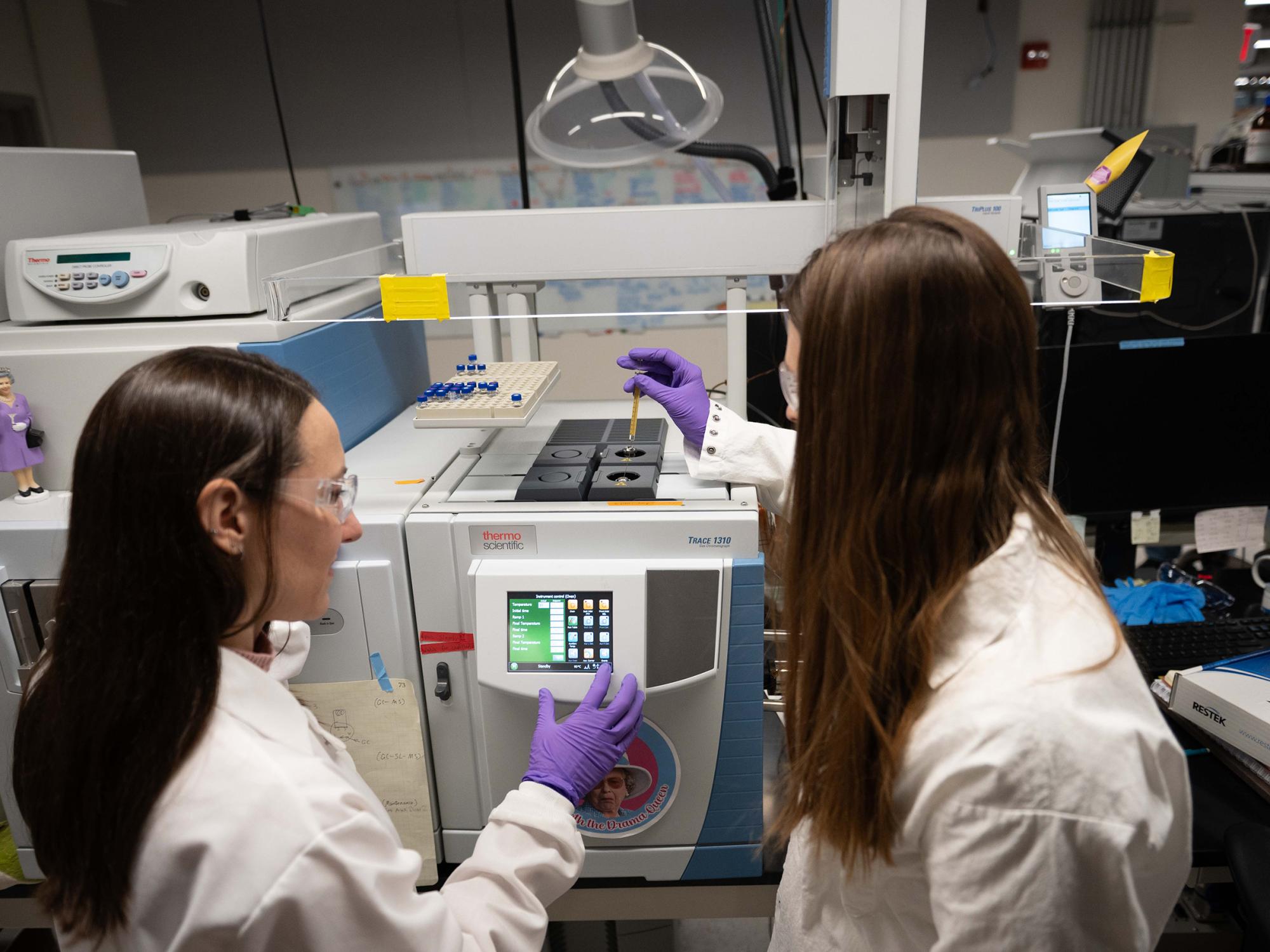

The researchers used highly sensitive tools to measure isotopes in extremely small amounts. They could detect molecules down to picomoles. Baczynski said the work depended on custom equipment at Penn State.

“Here at Penn State, we have modified instrumentation that allows us to make isotopic measurements on really low abundances of organic compounds like glycine,” Baczynski said. “Without advances in technology and investment in specialized instrumentation, we would have never made this discovery.”

Meteorite studies can be messy due to Earth contamination. Bennu’s sample avoided much of that risk. It came straight from space; then stayed sealed and controlled.

For decades, scientists have used carbon-rich meteorites as natural labs. One of the best known is the Murchison meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969. Murchison holds many amino acids; and it has been studied for years.

The Penn State group compared Bennu’s amino acids to Murchison’s. The contrast was sharp.

“One of the reasons why amino acids are so important is because we think that they played a big role in how life started on Earth,” said McIntosh, co-lead author and a postdoctoral researcher in Penn State’s Department of Geosciences. “What’s a real surprise is that the amino acids in Bennu show a much different isotopic pattern than those in Murchison, and these results suggest that Bennu and Murchison’s parent bodies likely originated in chemically distinct regions of the solar system.”

In Bennu, the team identified 19 amino acids in a powdered sample labeled OREX-800107-183. Several came in “left” and “right” mirror forms. Many had carbon and nitrogen isotope values above typical Earth values. That supports a space origin.

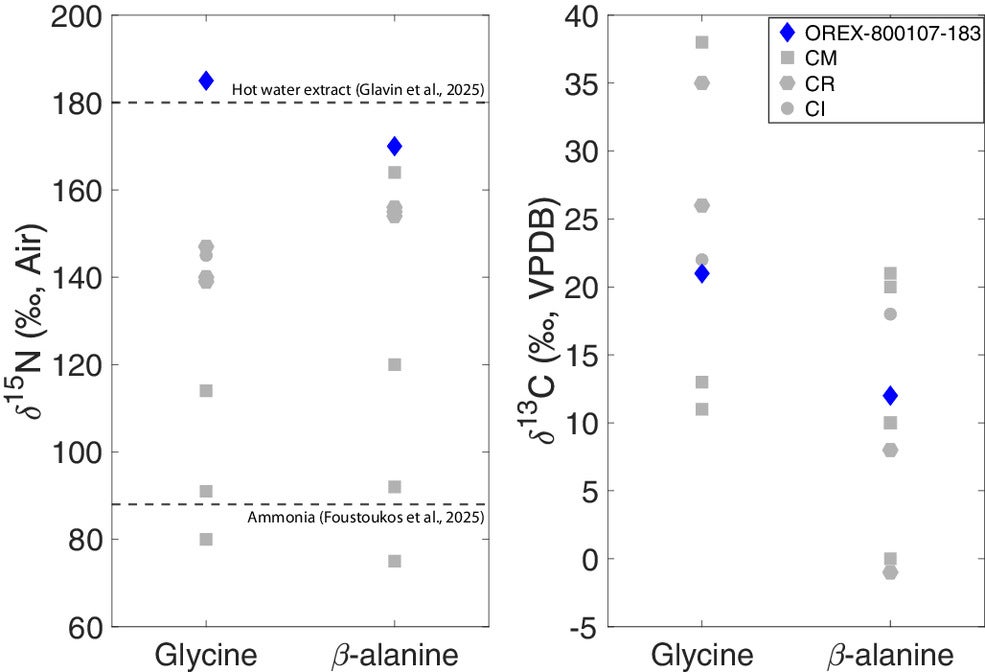

Bennu’s glycine showed a carbon isotope value of +21 ± 6‰. Its nitrogen isotope value was +185 ± 10‰. Bennu’s β-alanine measured +12 ± 6‰ for carbon; and +170 ± 4‰ for nitrogen.

When the team compared carbon values to Murchison, they looked similar within uncertainty. Nitrogen was the standout. Murchison’s glycine nitrogen value was +78 ± 6‰. Murchison’s β-alanine was +63 ± 4‰. Bennu’s were much higher.

For years, a popular idea for making glycine in space rocks has been Strecker synthesis. In that pathway, hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, and an aldehyde or ketone react in liquid water. It is a “wet” recipe.

Bennu’s glycine did not match that story cleanly. The team measured glycine’s two carbon positions separately. In Bennu, those two carbons looked similar within error. In Murchison, they looked very different.

They also measured certain aldehydes and ketones in another Bennu extract. Those compounds were more depleted in carbon-13 than Bennu’s glycine. That mismatch made a Strecker-only explanation less likely for Bennu.

So the researchers pointed to another route: chemistry in ice exposed to radiation. In that picture, ultraviolet light or other radiation hits frozen ices. It creates reactive fragments. Later, those fragments can become amino acids.

Baczynski summarized it as amino acids forming “in frozen ice exposed to radiation in the outer reaches of the early solar system.” The study says this kind of “ice photochemistry” could make nitrile precursors. Those precursors could later turn into amino acids.

The team noted one caveat. Bennu’s formaldehyde carbon isotope value has not been measured yet. If it turns out to be unusually enriched, Strecker chemistry could still play a role. More measurements are planned.

Bennu also brought a surprise about mirror-image molecules. Amino acids can come in left-handed and right-handed forms. Many scientists assume the pair should share the same isotope signature.

Bennu challenged that. The two mirror forms of glutamic acid had very different nitrogen values. D-glutamic acid measured +277 ± 7‰. L-glutamic acid measured +190 ± 32‰.

“We have more questions now than answers,” Baczynski said. “We hope that we can continue to analyze a range of different meteorites to look at their amino acids. We want to know if they continue to look like Murchison and Bennu, or maybe there is even more diversity in the conditions and pathways that can create the building blocks of life.”

Other Penn State co-authors are Mila Matney, a doctoral candidate in geosciences; Christopher House, professor of geosciences; and Katherine Freeman, Evan Pugh University Professor of Geosciences at Penn State.

This work widens the list of places where life’s raw materials might form. If amino acids can arise in cold, irradiated ice; then more worlds may have the right chemistry early on.

It also helps guide future sample-return missions. Isotope tests can point to where a body formed; and what it experienced. That can shape which targets scientists choose next.

Finally, the mirror-image glutamic acid result warns against easy assumptions. If paired molecules can record different nitrogen histories; then researchers may need new models for how organics interact with minerals and fluids in space.

Research findings are available online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The original story “Asteroid Bennu sample finds life’s building blocks formed in space ice” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Asteroid Bennu sample finds life’s building blocks formed in space ice appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.