A quiet problem has followed cancer immunotherapy for years. The immune system can be taught to fight, then it fades. T cells surge, then stall, then slip into exhaustion.

Researchers at Université de Montréal think they have found one reason why that stall happens, and it does not come from the tumor at all. In a Nature study led by Dr. André Veillette, the team points to a molecule on immune cells called SLAMF6, and they show a way to block it.

Veillette directs the molecular oncology research unit at the Montreal Clinical Research Institute (IRCM), which is affiliated with Université de Montréal. His group describes SLAMF6 as an internal brake on T cells, one that can activate on the T cell surface without needing to bind a tumor cell.

Most people hear about immunotherapy through the idea of “releasing the brakes.” Drugs that block PD-1 or PD-L1 try to stop tumors from shutting immune cells down. Yet many patients do not respond, and others stop responding over time.

SLAMF6 looks different in this work. The team argues it can “self-activate” through homotypic cis interactions, meaning SLAMF6 molecules interact with each other on the same cell, sending a stop signal from within the T cell itself.

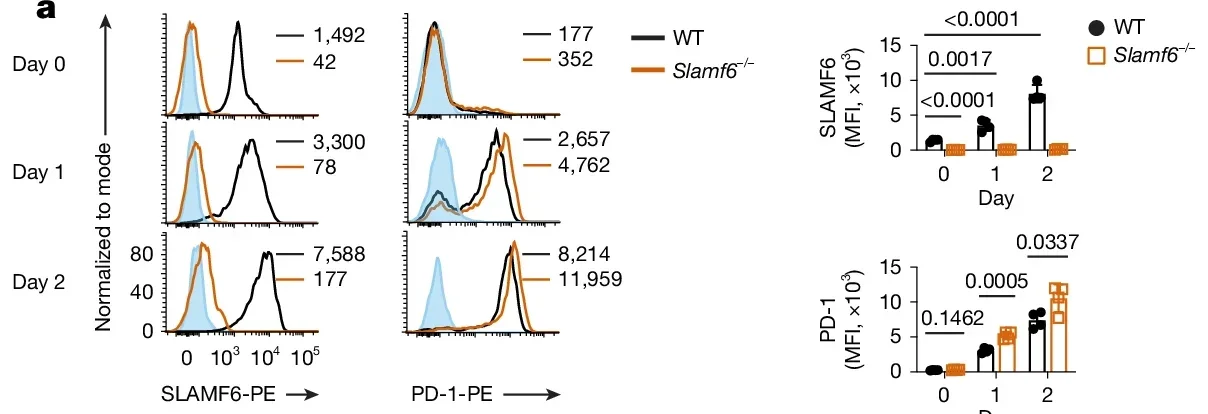

In mouse experiments, T cells lacking SLAMF6 (Slamf6−/−) were more active after certain types of stimulation. They proliferated more and produced more cytokines in response to CD3 stimulation, with or without CD28, though not after PMA and ionomycin, which bypass early T cell receptor signalling.

The paper also reports stronger tumor control in vivo in mouse tumor models. When OT-I CD8+ T cells from Slamf6−/− mice were transferred into tumor-bearing mice, tumor growth dropped compared with transfers using wild-type T cells. Those mice also had higher proportions of OT-I T cells and greater production of interferon-γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF).

That biology set up the therapeutic idea. If SLAMF6 can tamp down T cells through these cis interactions, then blocking those interactions might keep T cells functional longer.

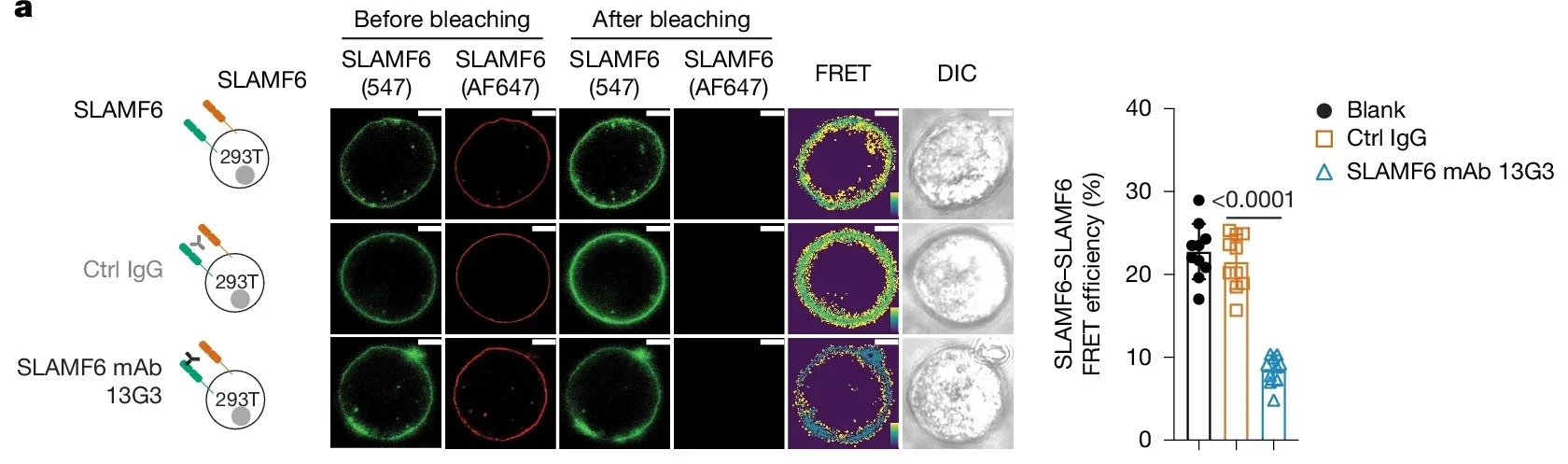

The researchers tested existing SLAMF6 antibodies first. A mouse antibody known as 13G3 had been described as an agonist in earlier work. In this study, it behaved more like a partial blocker, reducing energy transfer between SLAMF6 molecules in FRET assays by about 60%. It also boosted activation responses, but only partially compared with full SLAMF6 deficiency.

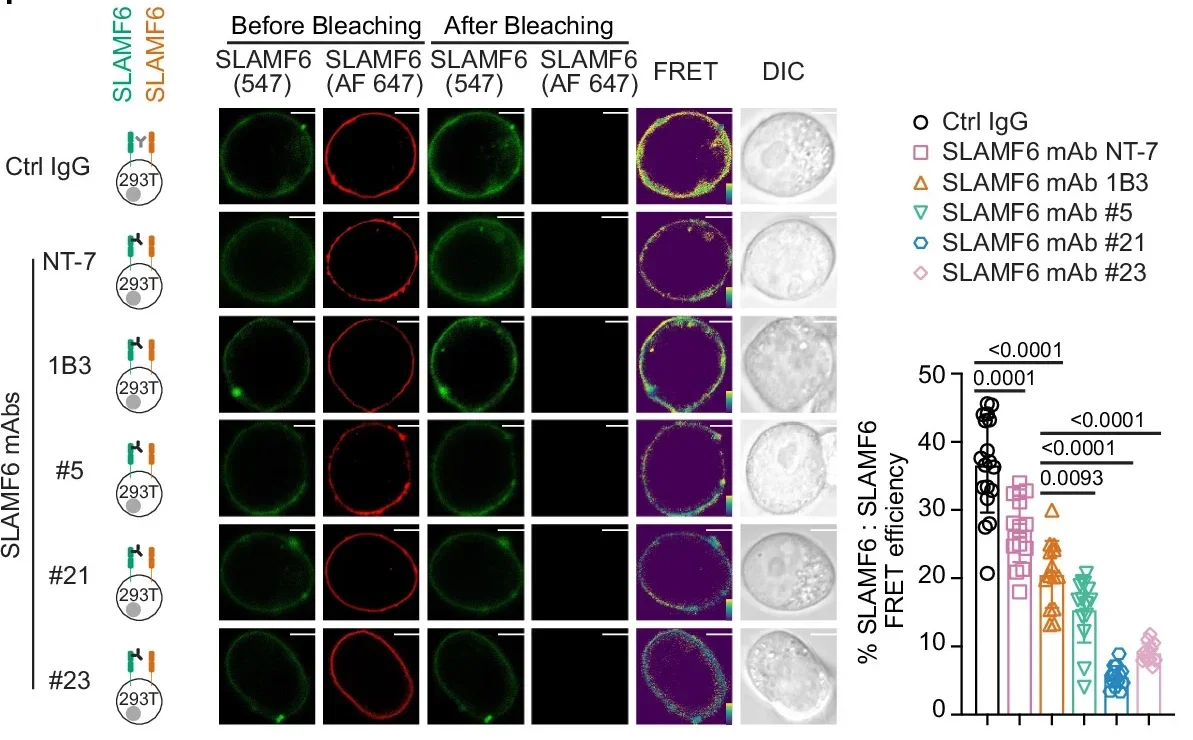

Then came the more direct approach. The group developed new monoclonal antibodies designed to prevent SLAMF6 from binding to itself. In the summary material provided, they describe effects such as more activation of human T cells, higher numbers of resilient immune cells, fewer exhausted T cells, and strong anti-tumor responses in mice.

The deeper sections of the source lay out how they screened human SLAMF6 antibodies for their ability to block SLAMF6–SLAMF6 cis interactions. In FRET assays, some antibodies were far more potent than others. SLAMF6 mAb 21 reduced energy transfer by about 90%, and mAb 23 by about 80%. Those same antibodies drove much larger increases in human T cell activation responses, while other antibodies had little effect.

A proximity ligation assay supported the idea that SLAMF6 molecules sit close together in human T cells, consistent with cis interactions. Blocking antibodies reduced that proximity signal without lowering surface expression of SLAMF6.

Blocking SLAMF6 mattered in living tumor models too. In mice inoculated with E.G7 tumors, treatment with a potent blocking antibody reduced tumor growth compared with control antibodies. Tumors from treated mice showed more tumor-infiltrating OT-I T cells and higher IFNγ and TNF.

The work also tracks exhaustion-associated markers in tumor-infiltrating T cells. Blocking SLAMF6 shifted the balance away from TCF-1−TIM-3+ cells and toward TCF-1+TIM-3− cells, alongside changes in markers like PD-1, TOX, TIGIT, LAG-3, and TIM-3. The authors frame this as compatible with fewer exhausted T cells, while noting that some markers can rise in activated cells too.

The study also explores combining SLAMF6 blockade with PD-L1 blockade in an MC-38 tumor model. Each treatment reduced tumor growth, and the combination produced the strongest effect in that setting.

There is a catch, and the paper does not hide it. When Slamf6−/− T cells were used in a graft-versus-host disease model, mice receiving those T cells had shorter survival and more weight loss. That result fits the larger concern with checkpoint-style approaches: pushing the immune system harder can raise the risk of collateral damage.

The authors also note unanswered questions. It is not known whether SLAMF6 blockade prevents exhaustion at the single-cell level. They also flag that T cells may become irreversibly exhausted at a terminal stage, limiting how much any blockade can reverse.

Still, the institutional summary points to a possible clinical path. Veillette’s team wants to test these antibodies in early-phase clinical trials for people with solid tumors or blood cancers, looking at safety and efficacy.

“The discovery made by Dr. Veillette’s team opens the door to a new chapter in immunotherapy,” said IRCM president and scientific director Dr. Jean-François Côté.

“By identifying an internal brake that had until now gone unrecognized and by developing antibodies capable of neutralizing it, our researchers are offering an innovative solution to the limitations of current treatments,” he said.

“Rooted in a strategic vision to develop precision therapeutics, this breakthrough brings real hope to many patients and stands as a strong example of the impact of the translational research conducted at the IRCM.”

If SLAMF6 blockade holds up beyond mice, it could widen the logic of immunotherapy. Instead of only interrupting signals imposed by tumors, it could target a self-contained brake on T cells. That matters most for patients who do not respond to PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors, or who respond and then lose that benefit.

The study also underlines a familiar tradeoff. Stronger T cell activity can improve tumor control, but it can also increase the risk of harmful immune responses.

The paper reports no evidence of cytokine storm in the tumor experiments described, yet the graft-versus-host disease results keep the safety question front and center as the researchers consider early-phase trials.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

The original story “Scientists discover why some cancer treatments stop working” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists discover why some cancer treatments stop working appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.