An elephant can lift a log, swing sand onto its back, and still pick up a peanut without crushing it. That mix of strength and delicacy has always looked a little mysterious, especially because elephants have thick skin and relatively poor eyesight.

A new study says part of the answer sits on the trunk itself. Along the dorsal and lateral surfaces, roughly 1000 whiskers act like a sensing array. Researchers report that these whiskers are built with “functional gradients” that make contact feel different depending on where it happens along each whisker.

The work, published in Science, comes from an interdisciplinary German collaboration led by the Haptic Intelligence Department at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS).

The research was led by postdoctoral researcher Dr. Andrew K. Schulz and Prof. Katherine J. Kuchenbecker at MPI-IS, working with neuroscientists from Humboldt University of Berlin and materials scientists from the University of Stuttgart. Schulz, the study’s lead author and an Alexander von Humboldt postdoctoral fellow, described how the project began: “I came to Germany as an elephant biomechanics expert who wanted to learn about robotics and sensing. My mentor, Prof. Kuchenbecker, is an expert on haptics and tactile robotics, so a natural bridge was for us to work together on touch sensing through the lens of elephant whiskers.”

To do that, the team imaged and characterized 5-cm-long whiskers from elephants and cats down to the length scale of one nanometer, which is 1 billionth of a meter.

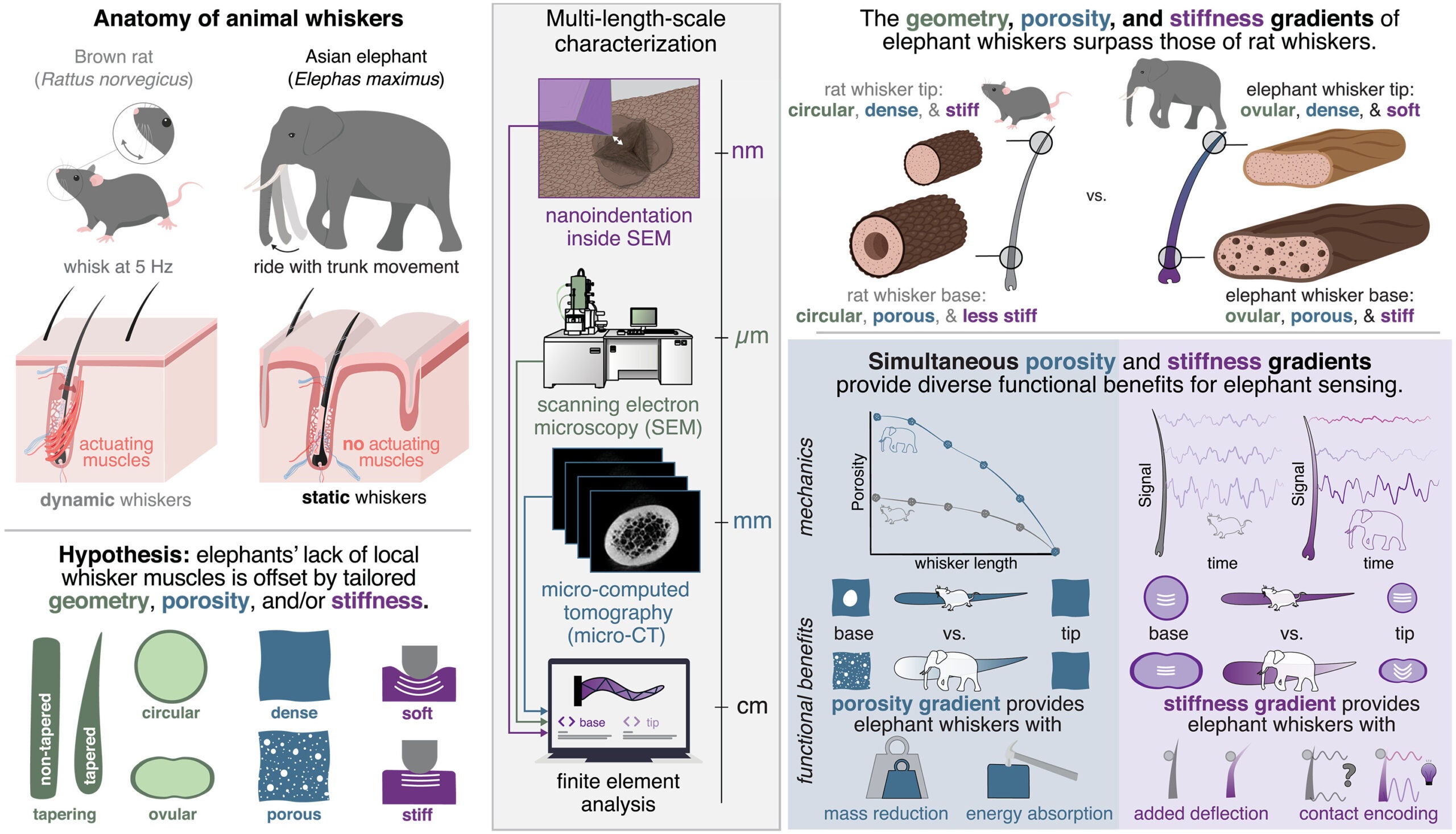

They focused on three basics that shape how a whisker behaves during contact: geometry, porosity, and stiffness.

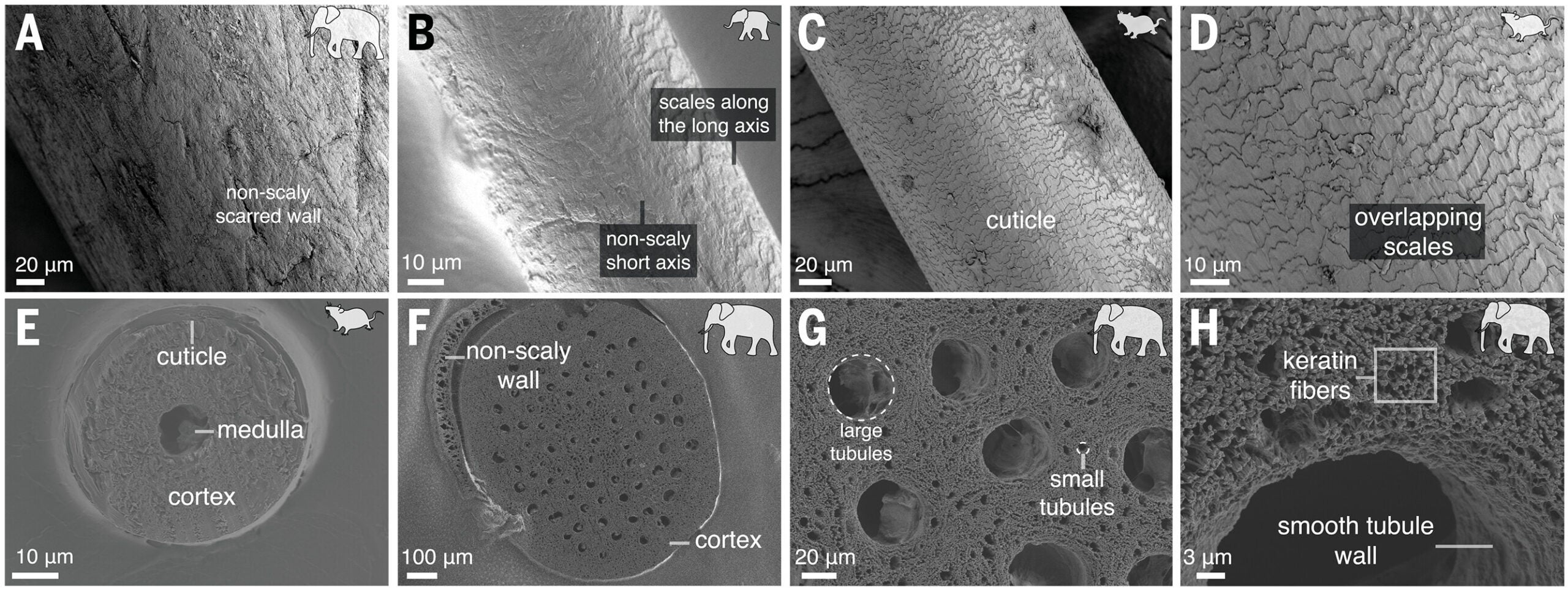

At first, the researchers expected elephant trunk whiskers to resemble those of mice and rats, which taper, have a circular cross-section, stay solid, and keep stiffness fairly uniform. Micro-CT showed something else.

Elephant whiskers can be thick and blade-like, with a flattened cross-section. The base can be hollow, with long internal channels that resemble structures seen in sheep horns and horse hooves. That porous architecture reduces mass and provides impact resistance, which matters because elephants eat hundreds of kilograms of food every day and those whiskers never grow back.

The paper also separates whiskers from two trunk regions. Distal trunk whiskers are thin, highly tapered, and blade-like. Their elongated cross sections align with the trunk’s circumferential wrinkles, which affects how they bend.

Proximal trunk whiskers are thicker, only gently tapered, and nearly circular. They can also be wavy, with radius changes along the length.

The most surprising twist came from stiffness. Using nanoindentation, the researchers pushed into whisker walls with a diamond cube indenter the size of a single cell. Indentation at the base and tip of elephant and cat whiskers showed a shift from a stiff, plastic-like base to a soft, rubber-like tip.

Schulz compared trunk whiskers to elephant body hair and found a contrast. “The hairs on the head, body, and tail of Asian elephants are stiff from base to tip, which is what we were expecting when we found the surprising stiffness gradient of elephant trunk whiskers.”

The measurements put numbers on that gradient. In a 2-week-old Asian elephant, the distal whisker base modulus measured 0.57 ± 0.02 GPa and the tip measured 0.1013 ± 0.004 GPa at an indentation depth of 2500 nm. In adults, the base modulus rose to 2.99 ± 0.28 GPa while the tip measured 0.0706 ± 0.008 GPa at 2500 nm depth, spanning two orders of magnitude (P < 10−5).

Domestic cat whiskers showed a similar pattern, with a base modulus of 2.24 ± 0.05 GPa and a tip modulus of 0.01 ± 0.0005 GPa at 1500 nm depth (P < 10−5).

Material gradients can sound abstract until you feel them. To build intuition, Schulz and colleagues at MPI-IS 3D printed a scaled-up whisker with a stiff, dark base and a soft, transparent tip.

Then the project turned oddly ordinary. Kuchenbecker carried the prototype through the institute and tapped it on columns and railings. She recalled, “I noticed that tapping the railing with different parts of the whisker wand felt distinct – soft and gentle at the tip, and sharp and strong at the base. I didn’t need to look to know where the contact was happening; I could just feel it.”

That simple walk helped crystallize the idea: the stiffness gradient might encode contact location.

To test that idea, the researchers built computational modeling tools and ran finite element analysis (FEA). Their simulations suggest that shifting from a stiff base to a soft tip helps an animal sense where contact happens along a whisker.

Schulz put it this way: “It’s pretty amazing! The stiffness gradient provides a map to allow elephants to detect where contact occurs along each whisker. This property helps them know how close or how far their trunk is from an object…all baked into the geometry, porosity, and stiffness of the whisker. Engineers call this natural phenomenon embodied intelligence.”

In one set of results, whiskers with a tip-to-base modulus ratio of 10−2 showed dynamic differences compared with other designs. The first modal resonance peak was 3.5 times that of whiskers with the inverse ratio. The first natural frequency was 25% lower than that of homogeneous whiskers, though the porous base increased frequencies in another part of the analysis.

The study also reports a striking contact-location effect in simulations. Referenced to tip contact, signal power at the base increased by 2000% when a graded whisker was plucked at 60% of its length, which the paper describes as an additional 4 dB of signal power transmitted to the base.

For elephant biology, the work offers a concrete way to connect trunk behavior to a physical design: geometry, porosity, and stiffness may shape what mechanoreceptors at the whisker base feel during contact.

For robotics, the team is aiming at sensors that rely less on heavy computation. Schulz framed one direction clearly: “Bio-inspired sensors that have an artificial elephant-like stiffness gradient could give precise information with little computational cost purely by intelligent material design.” Lena V. Kaufmann, a co-author at Humboldt University of Berlin, added the neuroscience angle: “Our findings contribute to our understanding of the tactile perception of these fascinating animals and open up exciting opportunities to further study the relation of whisker material properties and neuronal computation.”

If those ideas translate, designers could build whisker-like probes that “tell” you where contact happened through their materials alone.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

The original story “Elephant whiskers act like touch sensors built into the trunk” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Elephant whiskers act like touch sensors built into the trunk appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.