Sweat does more than burn calories. It also sparks chemistry that can quiet hunger, at least in mice. A new study from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, Stanford University School of Medicine and collaborating institutions shows how a small exercise-made compound can dial down appetite through a specific brain pathway. The work focuses on a molecule called Lac-Phe and explains, step by step, how it can lead to weight loss by changing how hunger neurons behave.

“Regular exercise is considered a powerful way to lose weight and to protect from obesity-associated diseases, such as diabetes or heart conditions,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yang He, assistant professor of pediatrics; neurology at Baylor College of Medicine and investigator at the Duncan NRI. “Exercise helps lose weight by increasing the amount of energy the body uses; however, it is likely that other mechanisms are also involved.”

This study leans into that “other mechanisms” idea. The researchers did not challenge the basics of weight loss. Instead, they asked why appetite often shifts after intense activity. They also asked how exercise might send a signal to the brain that says, “not now.”

Lac-Phe, short for N-lactoyl-phenylalanine, stood out for a reason. The team had previously found it spikes in the blood after intense exercise. That pattern appeared not only in mice, but also in humans and racehorses. In earlier work, when the researchers gave Lac-Phe to obese mice, the animals ate less and lost weight. The team also saw no negative side effects in those mice. Still, one key question remained: what does Lac-Phe actually do inside the brain?

To find the answer, the researchers looked where appetite decisions start. The hypothalamus acts like a control room for hunger, energy use, and body weight. Inside it, different neuron groups push and pull on feeding behavior.

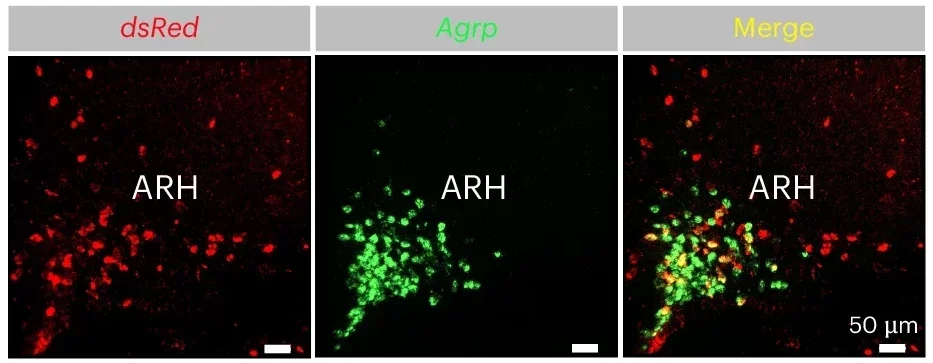

The team focused on two neuron types in mice. One group, called AgRP neurons, sits in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. These neurons drive hunger. When they fire, eating tends to rise. Another group, called PVH neurons, sits in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. These neurons help suppress hunger.

The wiring between them matters. AgRP neurons normally send signals that inhibit PVH neurons. That pattern supports hunger. When AgRP neurons quiet down, PVH neurons can ramp up. That shift supports reduced eating.

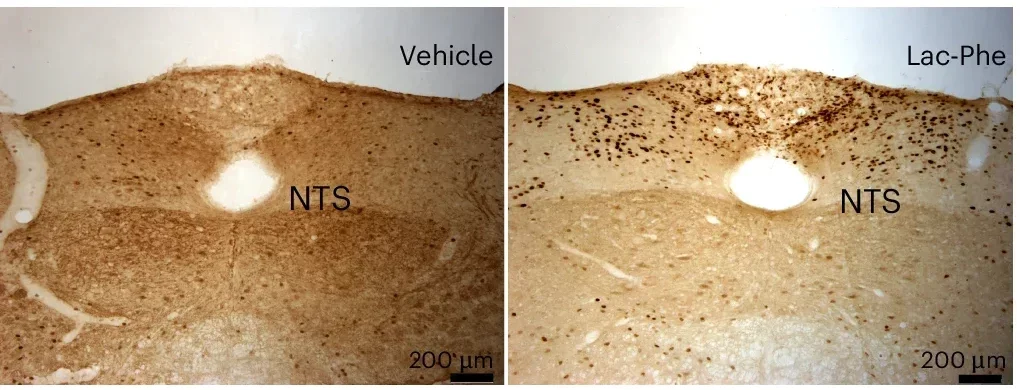

The researchers found that Lac-Phe plays directly into this circuit. They discovered that Lac-Phe inhibits AgRP neurons. As AgRP activity falls, PVH neurons become more active. Mice then eat less. The animals kept normal behavior, which supported the idea that Lac-Phe does not make them feel sick or distressed.

“Understanding how Lac-Phe works is important for developing it or similar compounds into treatments that may help people lose weight,” He said. “We looked into the brain as it regulates appetite and feeding behaviors.”

That line captures the study’s goal. It is not just about explaining a workout feeling. It is about mapping a clean biological pathway that could one day guide therapies.

A finding like this can sound simple, but the brain rarely is. The team had to show that Lac-Phe did not just correlate with eating less. They needed evidence of a cause-and-effect pathway.

They traced the chain: Lac-Phe directly inhibits AgRP neurons, which then allows PVH neurons to activate. That activation helps suppress hunger. The result shows up as lower food intake in mice.

The researchers also stress what did not happen. The mice did not show abnormal behavior. That detail matters because many appetite-suppressing approaches cause discomfort, stress, or sluggishness. The report describes normal behavior, which supports the idea that Lac-Phe works through a targeted hunger circuit rather than a broad “feel bad” effect.

The study also fits the team’s earlier work. Lac-Phe rose the most in blood after intense exercise, compared with other metabolites. It also reduced eating and weight in obese mice when given directly. Now the researchers can explain how the compound speaks to hunger neurons.

“This finding is important because it helps explain how a naturally produced molecule can influence appetite by interacting with a key brain region that regulates hunger and body weight,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Jonathan Long at Stanford University School of Medicine.

In plain terms, the study suggests that exercise can send a chemical message that lands in the brain’s hunger center and lowers the drive to eat.

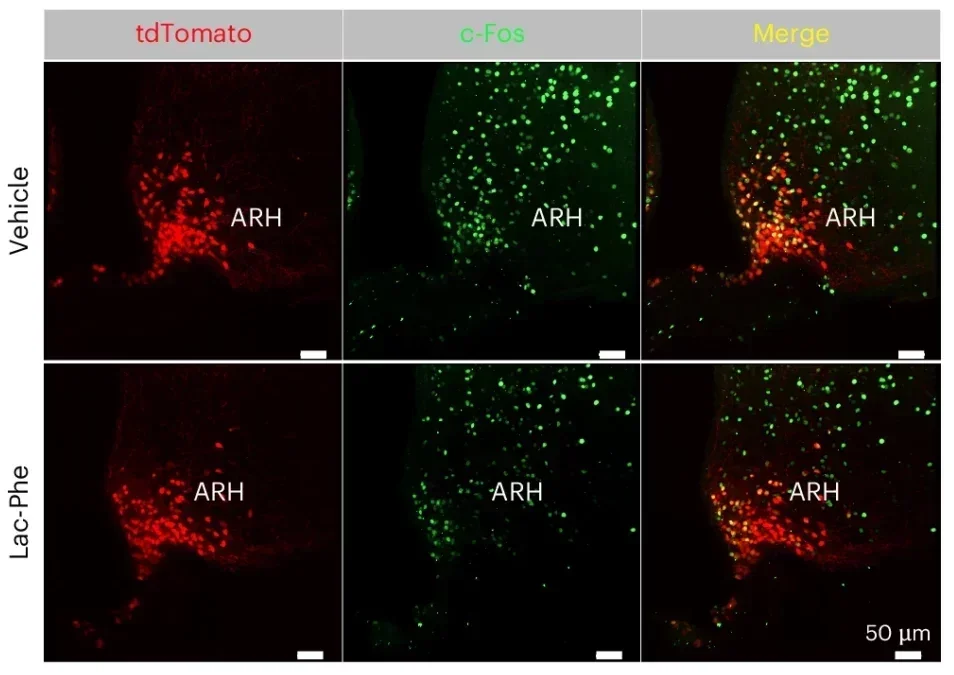

The team then dug deeper. They wanted to know how Lac-Phe shuts down AgRP neurons. They found the key player: a protein on AgRP neurons called the KATP channel.

KATP channels help regulate cell activity. When these channels activate, the neuron becomes less active. The researchers found Lac-Phe acts on these KATP channels in AgRP neurons. With the channels activated, AgRP neurons quiet down, which helps reduce appetite.

The team tested whether the KATP channel truly mattered. They blocked the channels using drugs or genetic tools. When they did, Lac-Phe no longer suppressed appetite. That result mattered because it identified an essential step in the mechanism. Without the KATP channel, Lac-Phe could not deliver its hunger-suppressing effect.

This kind of proof strengthens the story. It is not just a vague “exercise changes hormones” explanation. It names the neuron type, the brain region, and the molecular switch.

“The results also suggest the exciting possibility of targeting this newly discovered mechanism for weight management,” said co-corresponding author Dr. Yong Xu, currently at the University of South Florida.

That possibility comes with limits. The work focused on mice. The study does not claim a finished human therapy. But it does offer a roadmap for what to test next.

This research gives scientists a clearer picture of how exercise can shape appetite through the brain, not only through calorie burn. By identifying Lac-Phe as a key exercise-linked compound and showing it acts on AgRP neurons through the KATP channel, the study offers a precise target for future weight-management research.

In the long run, the work could help researchers design therapies that mimic a natural exercise signal. That might support people who struggle with obesity, overeating, or related metabolic risks.

The authors also point to important next steps, including studying how Lac-Phe works in different metabolic states, such as obesity versus leanness, learning how Lac-Phe travels to the brain, and testing whether it can be used safely and effectively as a therapy.

If those questions get answered, scientists could build more tailored approaches that support healthy weight loss and reduce the burden of obesity-linked disease.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Metabolism.

The original story “Sweating may naturally suppress hunger, scientists find” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Sweating may naturally suppress hunger, scientists find appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.