Older adults lose their ability to hear concrete sounds first, and with this loss come the more difficult aspects of hearing: the fuzzy edges of speech. As your hearing deteriorates, you are likely to lose familiarity with most of the sounds you have heard most often, which creates a challenge. However, this is not necessarily because they are hard to hear or not loud enough. A more significant challenge is clarity, where you have to put in much more mental effort to process and understand what someone has said.

For many years, studies have indicated that older adults who experience hearing loss also display an increased risk of cognitive decline. However, no viable biological mechanism linking the two has been identified. This may finally change, as researchers from Tiangong University and Shandong Provincial Hospital, led by Ning Li, have published evidence that they have identified a potential pathway for this relationship.

The objective of the research was to assess the Functional-Structural Ratio (FSR), a ratio derived from two different methods of measuring an individual’s brain activity and tissue structure through MRI, as a way to observe a potential linkage for how hearing loss and cognitive impairment may be related.

Researchers focused on the ratio of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF), measured from a resting-state functional MRI, and gray matter volume (GMV), measured from a structural MRI. They determined that the FSR would serve as an indicator of “imbalance” in brain regions associated with speech and higher-order processing.

By comparing their FSR data from older adults who have presbycusis with those who did not, the researchers were able to demonstrate that FSR is correlated with hearing and cognitive deficits. More notably, the association occurred in brain areas of speech processing and higher-order thinking.

To conduct the research, 110 right-handed Mandarin-speaking adults aged 50 to 74 years who were either diagnosed with presbycusis or had normal hearing were recruited. According to previous literature, presbycusis is defined as having a Pure Tone Average (PTA) > 25 dB HL for the average across four frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz.

In the presbycusis group, a total of 35 cases were considered mild, 19 were considered moderate, and one was classified as severe. Those with presbycusis but having hearing loss due to other conditions, those who had undergone surgical procedures for treatment of their hearing difficulties, those who used hearing aids, those with neurodegenerative diseases, and those who could not undergo MRI were excluded from this study.

Using traditional methodologies, each participant received complete hearing assessments that included the measurement of pure tone thresholds (0.125–8 kHz) in both ears and a Speech Reception Threshold (SRT). Participants underwent neuropsychological evaluation using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT), and Trail Making Test (TMT), with TMT-A administering the encoding task and TMT-B administering executive function tests.

Subsequent to these evaluations, each participant had a structural MRI performed to estimate the volume of gray matter and an 8-minute resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) performed to compute ALFF. Results were compared between those with presbycusis and those who had normal hearing, controlling for age, sex, and education. Statistical analysis was corrected for multiple comparisons.

Regional Functional Structure Relationships (FSR) were computed using ALFF and GMV. The researchers were able to use these computations to identify localized FSR changes, which traditional methods alone may have overlooked.

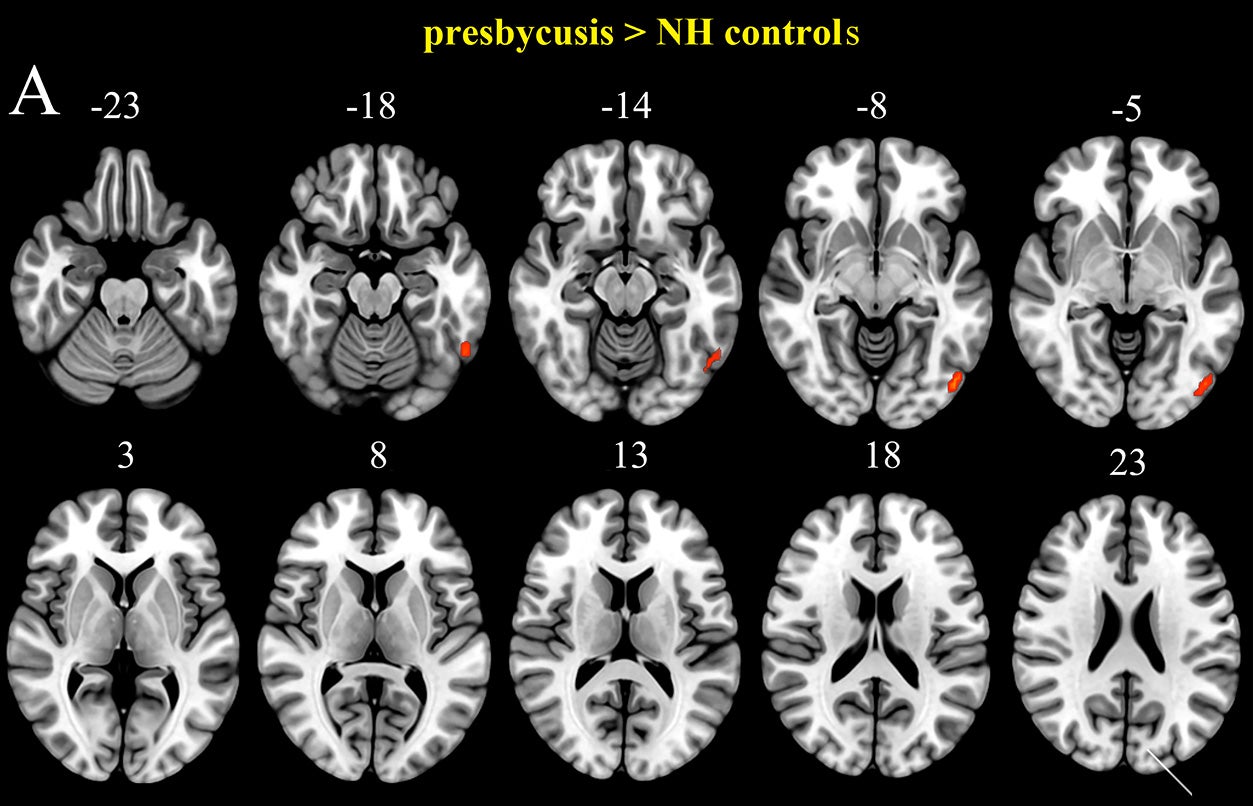

Methodological observations regarding GMV reductions observed in association with presbycusis across multiple brain regions were confirmed using anatomical comparison with those who had normal hearing. Included in these areas were the bilateral superior temporal gyrus and superior temporal pole, middle cingulate cortex, insula, Heschl’s gyrus, fusiform gyrus, and supplementary motor area. The right middle temporal gyrus, hippocampus, calcarine, precuneus, left putamen, medial superior frontal gyrus, and inferior parietal lobule also showed reductions in the presbycusis group compared to controls.

While some areas showed a reduction of ALFF for presbycusis relative to controls, the right inferior temporal gyrus, left calcarine, and inferior occipital gyrus all exhibited increased ALFF.

Overlapping areas of functional and structural changes were most pertinent when evaluating the research team’s central question. They found both ALFF and GMV alterations to overlap in four regions: the fusiform gyrus, precuneus, medial superior frontal gyrus, and putamen.

For example, some overlapping functional and structural regions in presbycusis had both ALFF and GMV change in unison, while other areas exhibited no correlation. There were significant negative correlations between ALFF and GMV for the left superior frontal gyrus (r = -0.320, p = 0.006) and right precuneus (r = -0.295, p = 0.009) for the presbycusis group. Meanwhile, the left fusiform gyrus (r = 0.280, p = 0.010) and left putamen (r = 0.321, p = 0.006) demonstrated significant positive correlations. These correlations were not found within the control group.

The major concentration of FSR discrepancies between the study groups was located in the same regions. When researchers compared people with presbycusis to participants with normal hearing, there were differences in the fusiform gyrus, medial superior frontal gyrus, putamen, and precuneus. The fusiform gyrus showed significantly reduced FSR in participants with presbycusis. The researchers then looked at the relationship between FSR and clinical measures for presbycusis participants only.

When comparing hearing threshold and speech recognition, the reported amount of FSR was the lowest in the right putamen. However, researchers reported significant negative correlations for both PTA (r = -0.274, p = 0.012) and SRT (r = -0.320, p = 0.003). On the left fusiform gyrus, both receptive speech threshold (r = -0.224, p = 0.042) and Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) scores (r = -0.299, p = 0.006) were significantly negatively correlated with FSR. In the right precuneus, MoCA scores (r = 0.221, p = 0.044) showed a positive correlation to FSR. In the right medial superior frontal gyrus, TMT-A scores (r = -0.248, p = 0.024) were negatively correlated with scores of FSR.

The relationship between FSR and clinical measures is evident. In this study, the relationship reported for hearing abilities is consistent with memory, as well as executive functioning, and occurs within regions of the brain where speech is processed and cognitive functioning occurs at higher levels.

In summarizing their work, Li stated: “The key point of clinical significance from our work is that protecting your hearing health may help to maintain your brain’s integrity.” Given the correlation of changes in the FSR (Function to Structure Ratio) with both hearing loss and cognitive decline, it may one day develop into a biomarker that provides doctors with a way of determining who is at greatest risk for dementia through brain scans.

This study presents a narrative around sensory deprivation, compensation, or both.

In developing their theory, the authors have relied upon the sensory deprivation hypothesis, which states that lower levels of auditory stimulation may initiate changes in the brain that may then contribute to cognitive decline. They state that their findings support the hypothesis. They also recognize the limitation of not being able to determine which occurred first. Was it the reduction of auditory stimulation that initiated the changes, or was the brain already changed prior to any reduction of auditory input?

This study is cross-sectional in nature, representing a single point in time. As indicated by the authors, the fact that the relationship between hearing loss and cognitive change identified in this study does not establish temporal order between the two variables. Thus, it is possible that hearing loss is an underlying factor for those changes in the brain, but likewise the changes in the brain may have already existed prior to any decrease in auditory input. Residual confounding and reverse causation cannot be ruled out.

Further, the authors cite several limitations. The limitation of sample size affected their ability to perform additional subgroup analyses. As such, they could not separate out the participants by their cognitive level of functioning. For example, the presbycusis group included individuals with intact cognitive ability, as well as those who were documented as having dementia, and a total of 26 had mild cognitive impairment. As a result, without separating out the groups, some of the differences in both structure and function attributable to presbycusis may, in fact, also be due to cognitive impairment.

As for the FSR itself, the authors point out that all ratio measures are inherently sensitive to measurement noise and scaling differences. They suggest validation of the FSR via regression modeling, multivariate fusion methodologies, and replication studies in larger independent datasets.

While this study does not provide concrete evidence of the causal links between hearing loss and dementia, it does provide an avenue for further studies. If the findings of FSR can be validated through additional studies, FSR can be incorporated into future studies investigating the impact of interventions on brain coupling measures over time and whether those changes correlate with cognitive performance.

Moreover, it may encourage clinicians to regard hearing health as a non-quality-of-life issue and instead recognize the relationship between structure and function in specific brain regions associated with auditory and speech processing, memory, and executive function.

Thus far, the clearest message from the authors is a cautious but concrete assertion: protecting hearing health may contribute to maintaining a healthy brain, and brain scans may ultimately provide an early warning of individuals who are most likely to have elevated risk of developing dementia.

Research findings are available online in the journal eNeuro.

The original story “Scientists reveal a link between hearing loss and cognitive decline” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists reveal a link between hearing loss and cognitive decline appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.