The first clue sits in a museum drawer, not on a windswept Arctic shore. It is a whale bone, marked and shaped by human hands. Around it are more bones, more tools, and a coastal story that reaches back 5,000 years.

New research from the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Department of Prehistory of the UAB says Indigenous communities in southern Brazil hunted large whales far earlier than scholars once believed. The work places active whaling in Babitonga Bay, in Brazil’s Santa Catarina state, about a thousand years before the earliest documented evidence from Arctic and North Pacific societies.

If you have ever pictured early whaling as a Northern Hemisphere breakthrough, this study asks you to redraw the map. The researchers argue these coastal communities built specialized tools, planned strategies, and social systems that made large-whale hunting possible long before the timeline most textbooks imply.

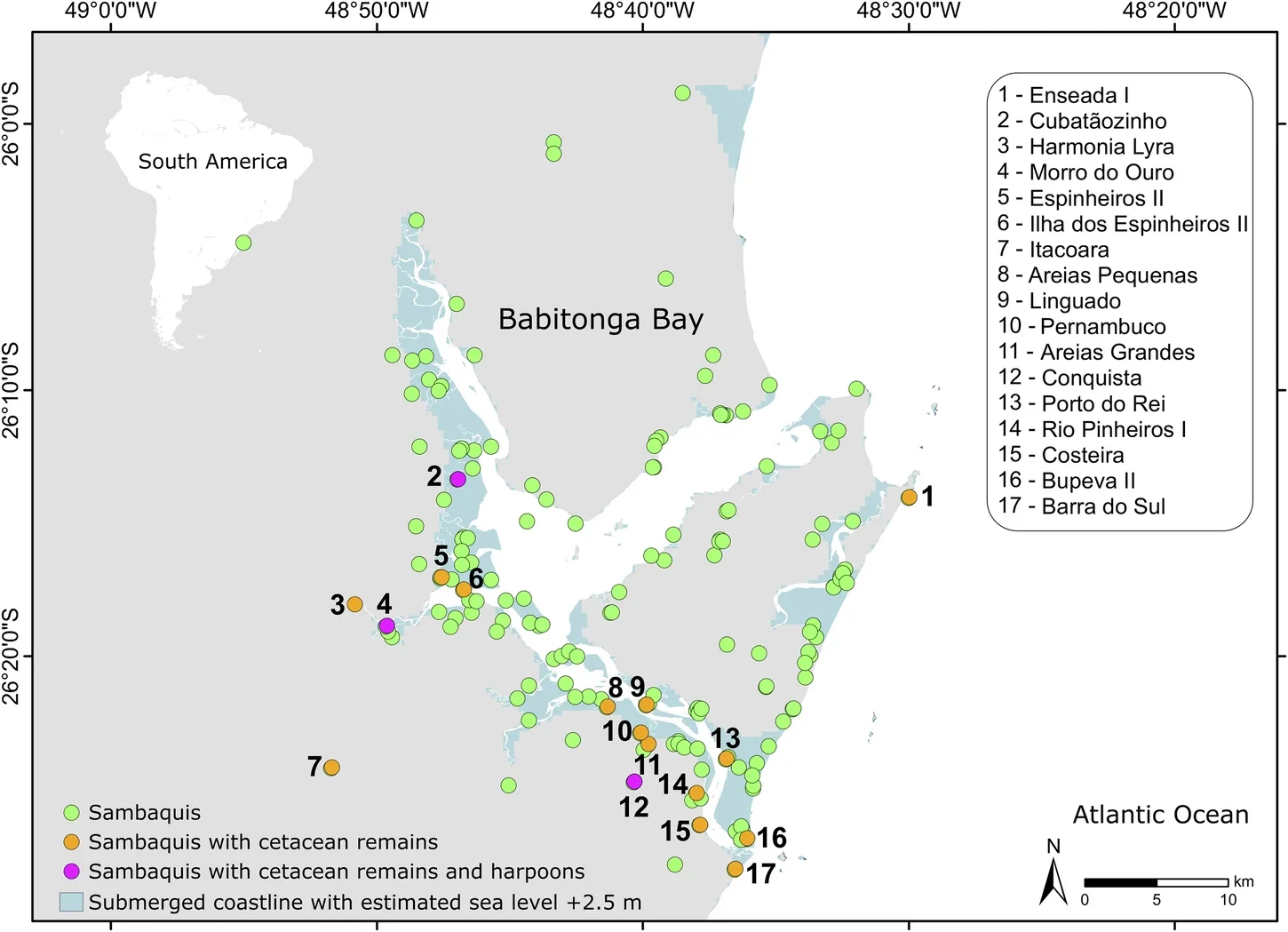

The evidence comes from sambaquis, monumental shell mounds built by Holocene societies along Brazil’s coast. These sites preserved bones, tools, and burials across long spans of time. Many sambaquis around Babitonga Bay no longer exist today. Urban growth erased parts of that record.

That loss makes the museum collections even more important. The team studied hundreds of cetacean bones and bone tools from the Babitonga region. The materials are housed at the Museu Arqueológico de Sambaqui de Joinville in Brazil. Researchers describe the collection as a rare archive, especially because so many original sites disappeared.

The study was led by ICTA-UAB researchers Krista McGrath and André Colonese, with an international team. Their work pulls together archaeology, lab science, and careful tool analysis to answer a basic question. Did people hunt whales, or only use stranded animals?

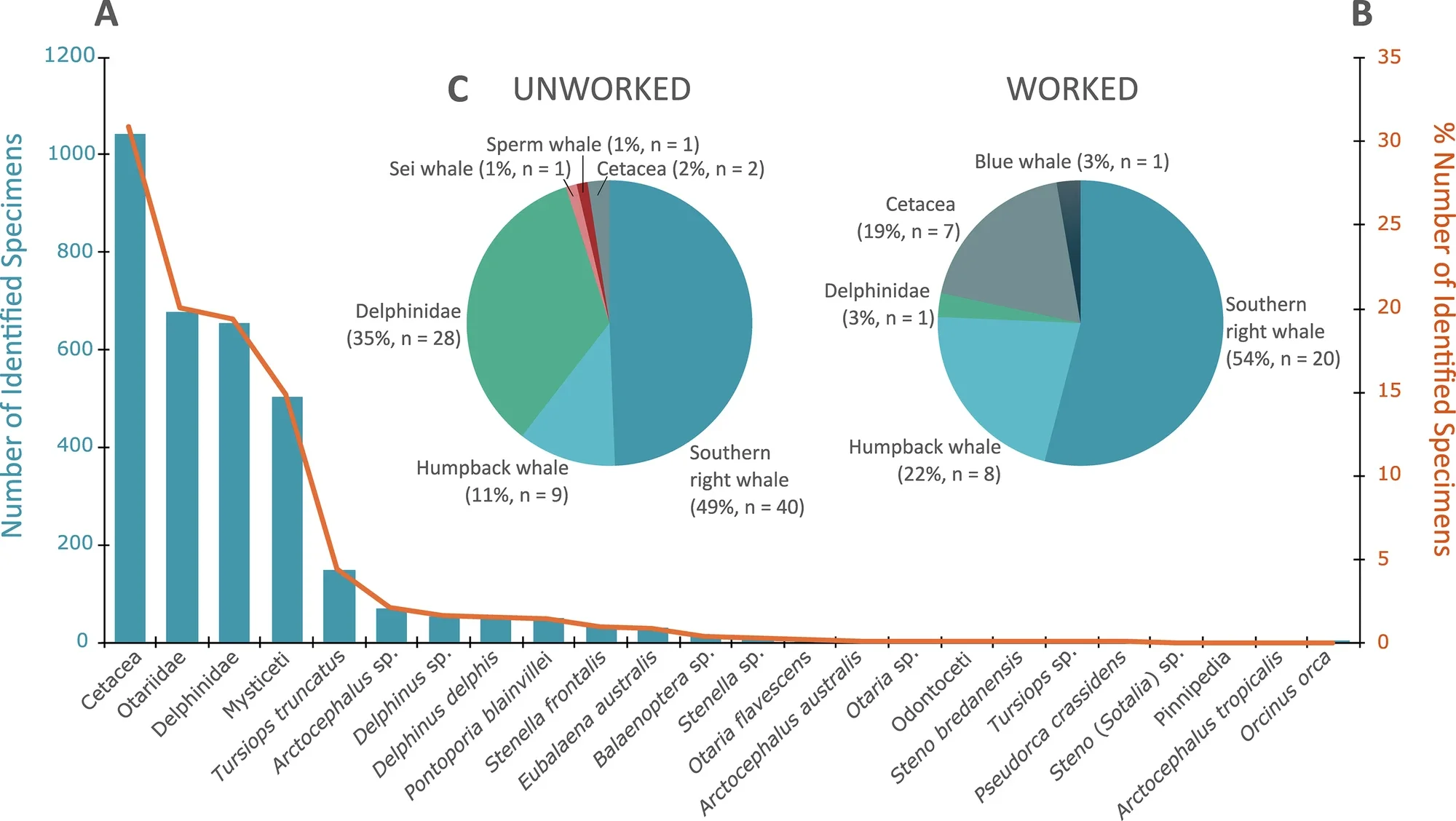

The team combined zooarchaeology, typological analysis, and molecular identification work called ZooMS. ZooMS helped identify cetacean remains even when bones were fragmented or reshaped into tools.

The results show a striking variety of marine life. The researchers identified remains of southern right whales, humpback whales, blue whales, sei whales, sperm whales, and dolphins. Many bones show clear cut marks linked to butchering.

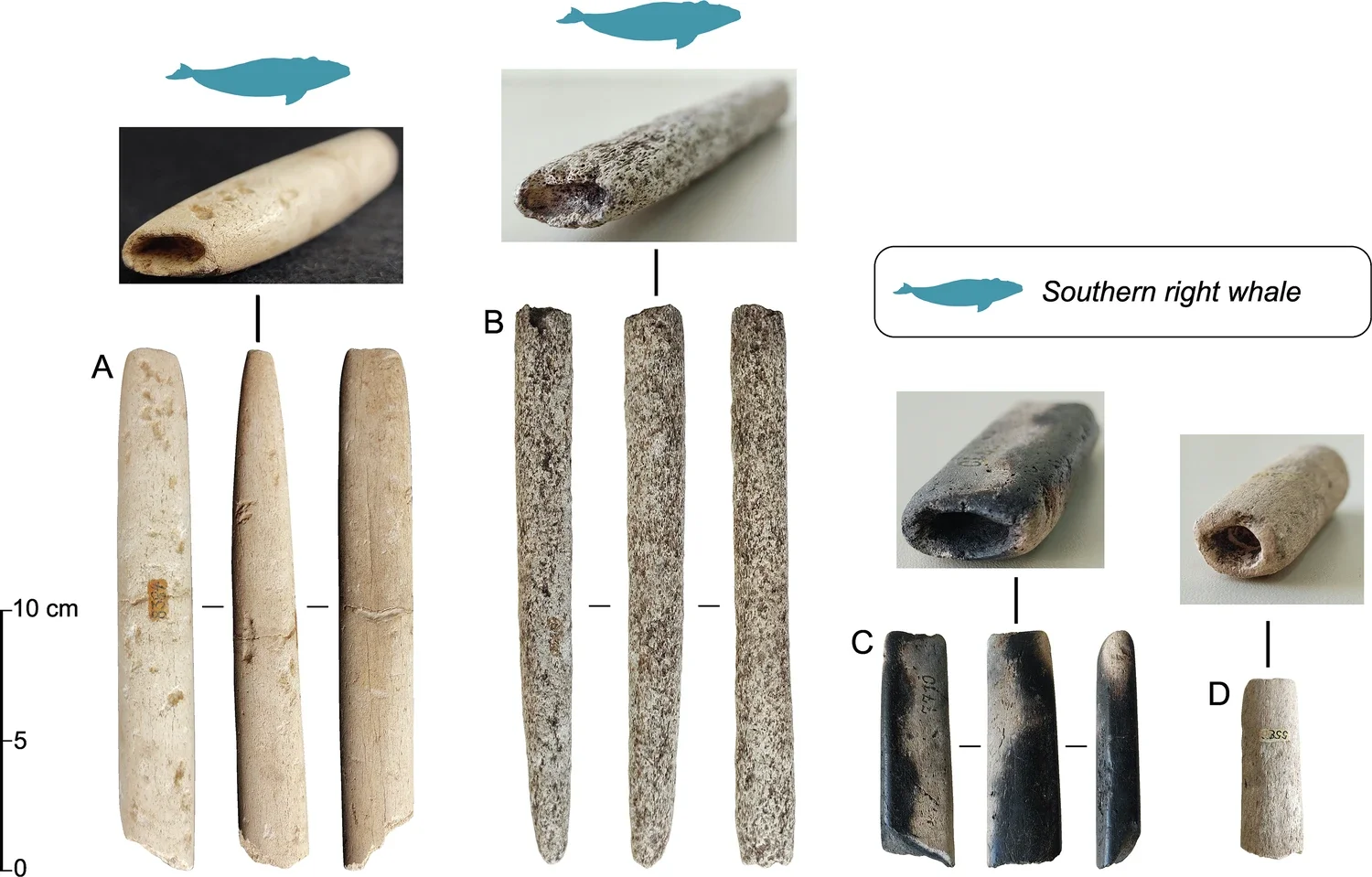

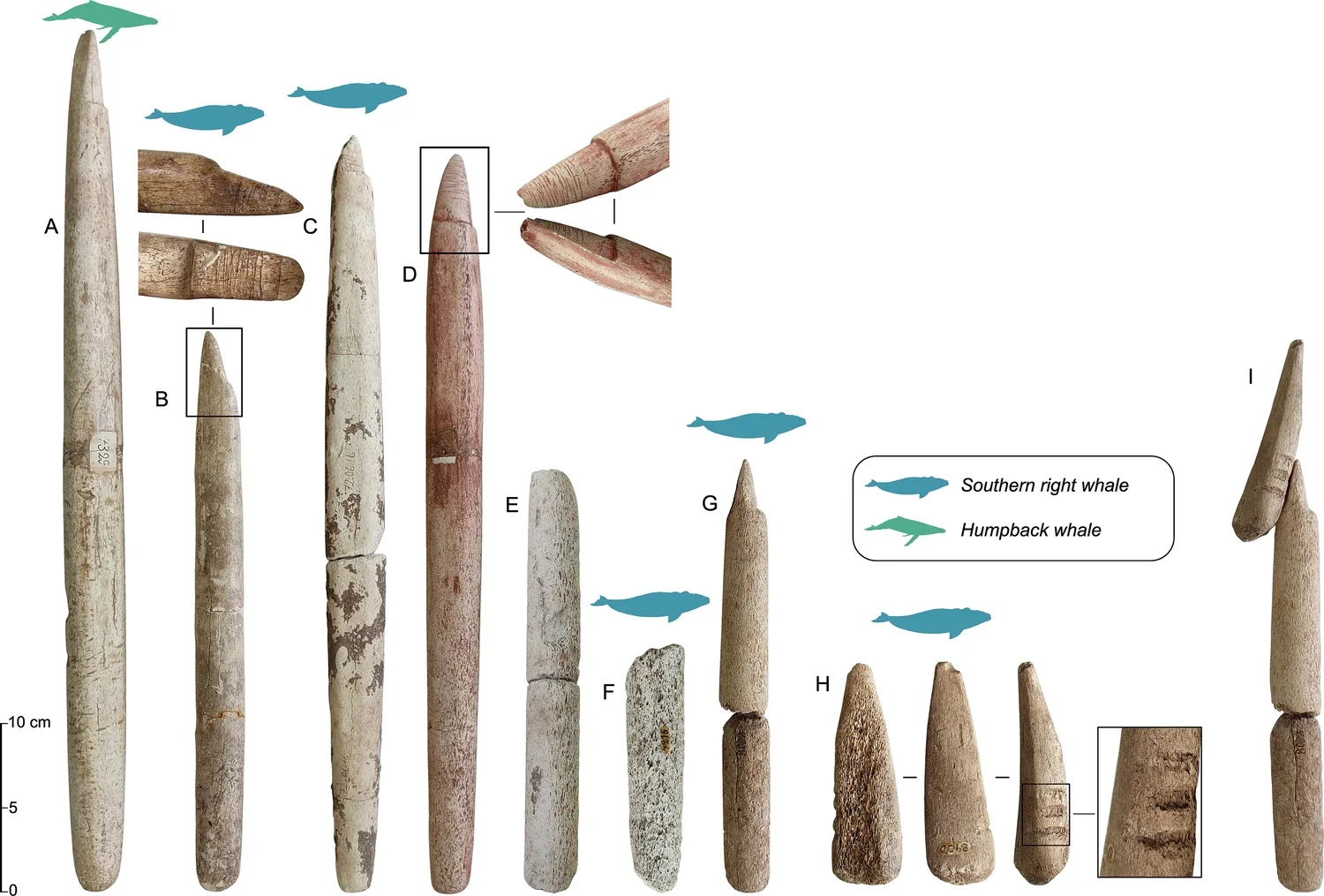

The study also documents large whale-bone harpoons. The researchers describe some of these as among the largest found in South America. Tool size matters here, because it signals intent. It is hard to explain massive harpoon parts as casual reuse.

The evidence stacks up across contexts. The team points to the abundance of whale bones, their presence in funerary settings, and the inclusion of inshore species. Together, these details support active hunting rather than simple scavenging.

“The data reveals that these communities had the knowledge, tools, and specialized strategies to hunt large whales thousands of years earlier than we had previously assumed,” says Krista McGrath, lead author of the study.

That quote lands with weight because it speaks to capability. It also speaks to coordination. Large-whale hunting is not a solo task. It requires planning, shared labor, and tools that work under pressure.

For years, it was common to describe sambaqui peoples mainly as shellfish collectors and fishers. This research argues that label is too small. The team says these coastal groups built a sophisticated maritime culture with specialized technology, collective cooperation, and ritual practices tied to large marine animals.

According to André Colonese, senior author of the study, “This research opens a new perspective on the social organization of the Sambaqui peoples. It represents a paradigm shift; we can now view these groups not only as shellfish collectors and fishers, but also as whalers.”

Dione Bandeira, a Brazilian archaeologist with more than 20 years of experience working on sambaquis, links the practice to long-term stability on the coast. “the results reveal a practice that made a significant contribution to the long-term and dense presence of these societies along the Brazilian coast.”

In other words, whaling was not a side note. The study frames it as a meaningful part of economy and identity. It also frames it as part of how communities stayed rooted in place.

The museum itself becomes part of this story. Ana Paula, director of the Museu Arqueológico de Sambaqui de Joinville, stresses the value of what has been protected. “the collections safeguarded at the Sambaqui Archaeological Museum in Joinville, especially the Guilherme Tibúrtius Collection, highlight the richness and vast potential of information on ancestral peoples that can still be explored in depth.”

The researchers say the findings also carry ecological value. The abundance of humpback whale remains suggests a broader historical distribution than the current main breeding areas off Brazil.

That matters when you look at the present coastline and modern sightings. “The recent increase in sightings in Southern Brazil may therefore reflect a historical recolonization process, with implications for conservation. Reconstructing whale distributions before the impact of industrial whaling is essential to understanding their recovery dynamics,” says Marta Cremer, a co-author of the paper.

The study does not treat the past as a sealed box. It treats it as a baseline. If you want to understand recovery, you need a clearer sense of where whales lived before major disruption. Museum bones can offer that kind of reference.

This study reshapes how researchers search for the roots of complex maritime life. It pushes scientists to look beyond the Northern Hemisphere when tracing early high-skill ocean hunting. That shift can change where future fieldwork happens and which collections become priorities. It also highlights the value of revisiting older museum archives with newer techniques, especially when original sites have been lost.

The work also supports conservation planning by offering a longer view of whale distribution. The researchers link humpback remains to a wider historical range, and they connect modern sightings to a possible recolonization process. That kind of long-term context can help experts set more realistic expectations for recovery. It can also guide questions about what “normal” looked like before industrial-scale impacts, even when direct records do not exist.

Finally, the findings strengthen public understanding of Indigenous history along Brazil’s coast. You see communities not only as shoreline residents, but as organized maritime specialists with technology, cooperation, and ritual life tied to the ocean. That fuller picture can influence how heritage is protected, how museum collections are supported, and how coastal development weighs what could be lost.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

The original story “Indigenous communities in southern Brazil hunted large whales 5,000 years ago” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Indigenous communities in southern Brazil hunted large whales 5,000 years ago appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.