A tube of mud can look like nothing special at first. Pull it from half a kilometer under Antarctic ice, though, and every smear starts to read like a diary.

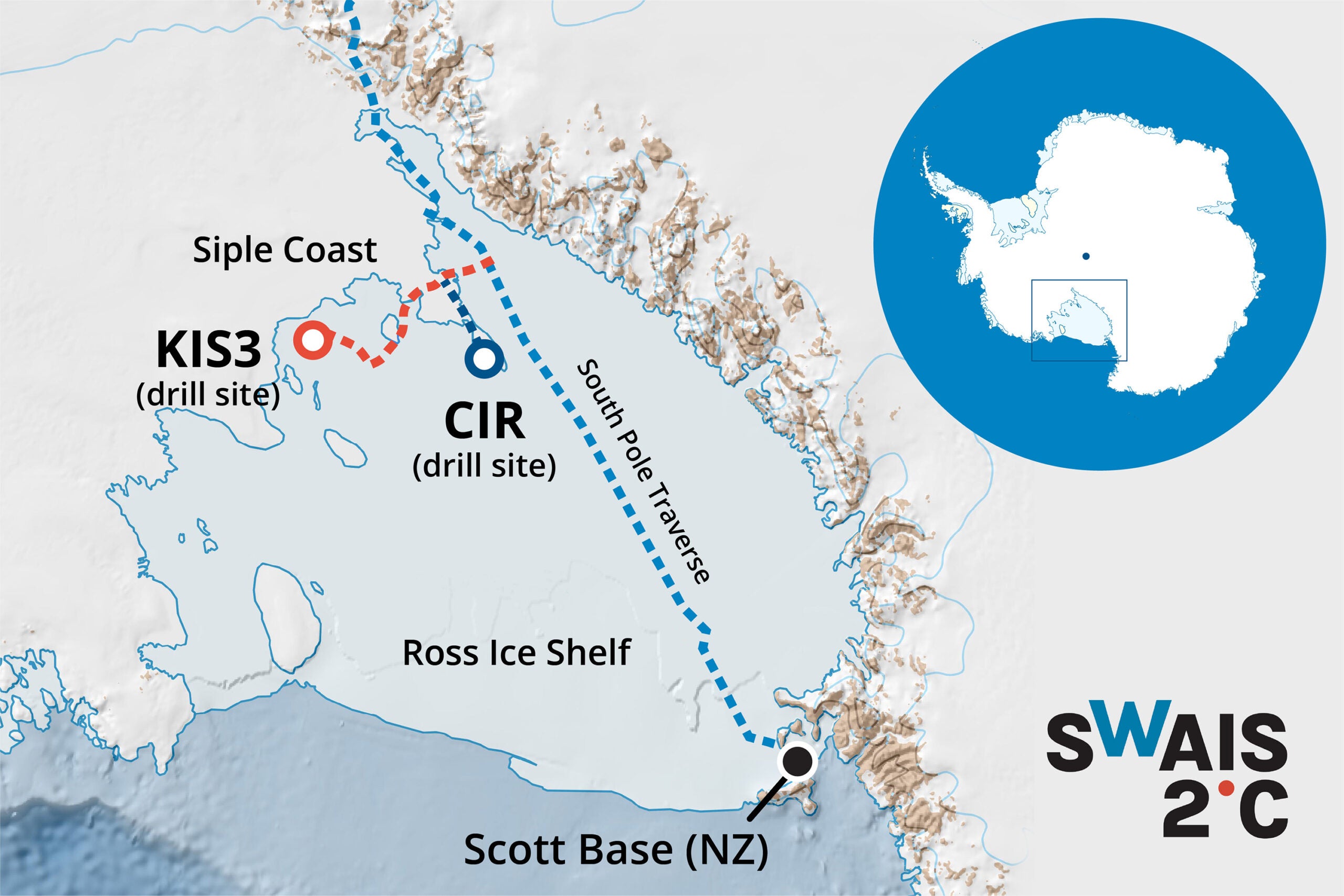

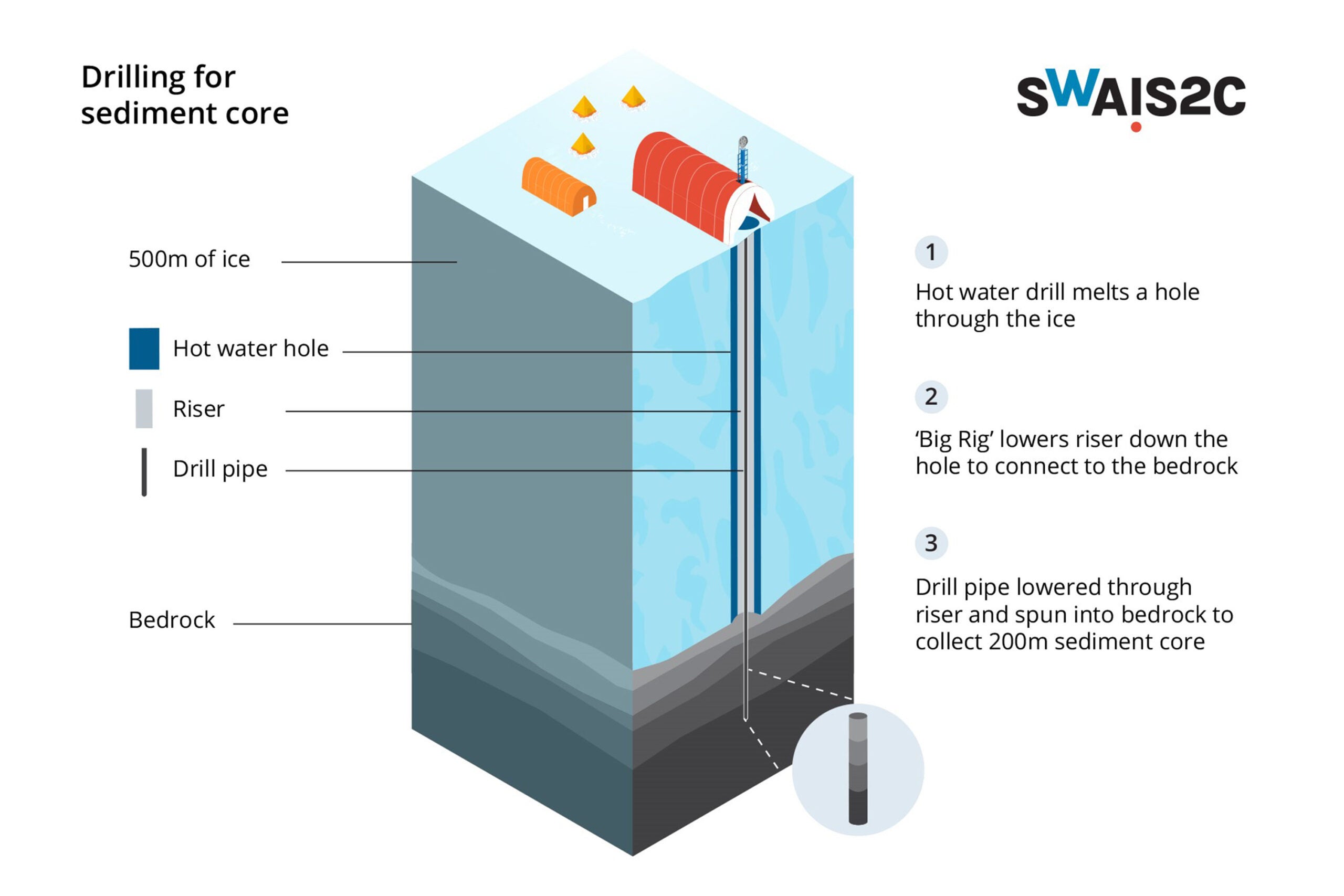

That is what an international team brought up at Crary Ice Rise, a grounded ice dome at the inner edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. After drilling through 523 meters of ice, the group recovered a sediment core 228 meters long, made of layered mud, gravel, and rock. By their account, it is far longer than any sediment core previously drilled from beneath an ice sheet, where earlier efforts were under 10 meters.

The aim is blunt and unsettling. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet were to melt completely, global sea level would rise about four to five meters. Scientists already track the region with satellites and with records taken near the ice sheet, under floating ice shelves, and in the Ross Sea and Southern Ocean. What has been missing is a direct, continuous archive from the ice-sheet margin itself during earlier warm climates, the kind that can show how the boundary between ice and ocean behaved when the planet ran hotter.

The drilling was part of SWAIS2C, short for Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to 2°C. The project is trying to pin down how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Ross Ice Shelf respond when global temperatures move above the 2°C threshold often used in climate planning.

“This record will give us critical insights about how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and Ross Ice Shelf is likely to respond to temperatures above 2°C,” said Huw Horgan, a co-chief scientist on the project affiliated with Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, ETH Zurich and the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL). He added that early indications suggest the core spans roughly the past 23 million years, including intervals when global average temperatures were well above 2°C higher than pre-industrial levels.

Those ages are not final. The team did preliminary dating in the field by identifying tiny fossils of marine organisms in some layers. A broader group of scientists from 10 countries will now refine and confirm the timing.

As the drill bit worked through sediment, the scientists say they saw a quick-changing mix of materials: fine muds, firmer gravels, and larger rocks embedded in the core.

“We saw a lot of variability,” said Molly Patterson, a co-chief scientist and professor of geology at Binghamton University. Some layers looked like what you would expect beneath an ice sheet like the one sitting on Crary Ice Rise today. Other sections resembled deposits formed in open ocean water, beneath a floating ice shelf, or near an ice-shelf margin where icebergs calve off into the sea.

Some of the most telling pieces were small. The core contained shell fragments and remains of marine organisms that require light to survive. That points to periods when at least part of the area was an ice-free ocean, not buried under thick grounded ice.

Scientists already suspect the region saw open water in the past, including episodes when the Ross Ice Shelf partly or completely retreated, and when the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have collapsed or pulled back significantly. The nagging uncertainty has been timing. Knowing when retreat happened, and what environmental changes lined up with it, is central to what SWAIS2C hopes to resolve, Patterson said.

The science depends on the core, and the core depended on logistics that were easy to describe and hard to execute.

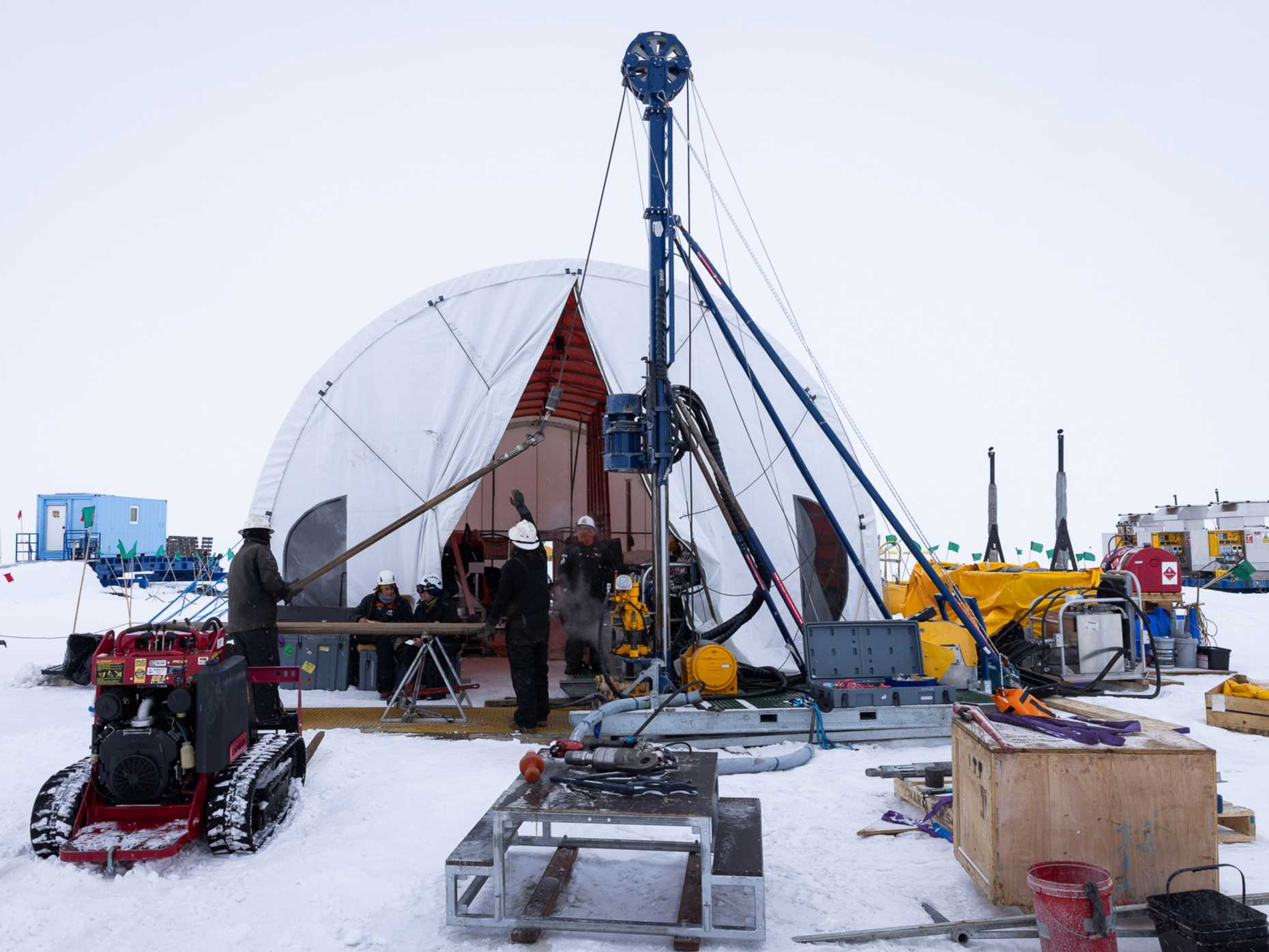

The drilling site sits roughly 700 kilometers from the nearest Antarctic stations. The field team included 29 people: scientists, drillers, engineers, and polar specialists. Two earlier attempts failed because of technical problems. The group expected trouble, in part because no one had tried to recover geological records from such depth under an ice sheet so far from major support bases.

“To our knowledge, the longest sediment cores previously drilled under an ice sheet are less than ten metres,” Patterson said. “We exceeded our target of 200 metres. This is Antarctic frontier science.”

The crew worked around the clock in shifts. They first used hot water to melt a hole through the ice, then lowered more than 1,300 meters of riser and drill string pipe. As each section of core came up, the team described it, photographed it, X-rayed the sediment tubes, and collected samples.

It is the kind of operation where relief comes in small, temporary bursts. “It was a great feeling when that first core came up, but then you start worrying about the next core and the next core after that,” Horgan said. “So, it’s stressful right up until the end.”

The project’s focus on 2°C is not abstract. Human activities are estimated to have increased average surface temperature by about 1.0°C above pre-industrial levels, and global temperatures are likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if warming continues at the current rate. Warming of 2°C could arrive as early as 2039 or as late as the mid-2060s, depending on emissions pathways.

Sea level has already risen about 22 centimeters since 1880, and the rise has been accelerating. One estimate in the material puts the current rate at about 3.6 millimeters per year. The IPCC has forecast a likely sea level rise range of 0.29 to 1.1 meters by 2100, but the source material stresses that uncertainty remains, and that some evidence suggests a substantially higher rise is possible, partly because Antarctica’s contribution is hard to pin down.

That uncertainty is one reason the West Antarctic Ice Sheet draws so much attention. Satellite observations show it is losing mass at an accelerating rate, and one estimate cited in the material puts its potential contribution to future sea level rise at about 4.3 meters. Much of the ice sheet sits on bedrock roughly 2,500 meters below sea level, and its floating ice shelves are exposed to warming ocean water, a setup that can make retreat difficult to stop once it starts.

Still, modern observations cover a short window. Past warm climates, captured in sediment, offer a longer view of how the system behaves when the planet pushes beyond recent experience.

Research findings are available online in the journal Scientific Drilling.

The original story “228-meter sediment core may predict future Antarctic ice sheet loss” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post 228-meter sediment core may predict future Antarctic ice sheet loss appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.