A vaccine usually trains your immune system to recognize one target. Here, the target is basically “anything that doesn’t belong in the lungs.”

That is the surprising promise behind a new mouse study from Stanford Medicine researchers and collaborators. The team reports an intranasal vaccine formula that protected mice for months against several respiratory viruses, two bacteria that often cause hospital infections, and even an allergen linked to asthma. The findings are published in Science.

“I think what we have is a universal vaccine against diverse respiratory threats,” said Bali Pulendran, PhD, the Violetta L. Horton Professor II and a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford. Haibo Zhang, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Pulendran’s lab, is the study’s lead author.

For more than two centuries, vaccine design has leaned on one big idea: antigen specificity. You show the body a harmless version of a pathogen’s calling card, and the immune system learns to recognize it later.

“That’s been the paradigm of vaccinology for the last 230 years,” Pulendran said.

That approach can stumble when microbes change quickly. “It’s becoming increasingly clear that many pathogens are able to quickly mutate. Like the proverbial leopard that changes its spots, a virus can change the antigens on its surface,” Pulendran said.

Many “universal vaccine” efforts still stay within one family, like flu viruses or coronaviruses, by aiming at viral parts that mutate less. A truly broad, catch-all respiratory vaccine has sounded unrealistic, even to people who work on vaccines. “We were interested in this idea because it sounded a bit outrageous,” Pulendran said. “I think nobody was seriously entertaining that something like this could ever be possible.”

The new mouse vaccine takes a different route. It does not try to mimic a virus or bacterium. Instead, it mimics the signals immune cells use to coordinate during infection, trying to keep the lung in a ready state.

The immune system has two major branches. Adaptive immunity is the specialist. It makes antibodies and T cells tuned to a particular invader, and it can remember that invader for years.

Innate immunity is the fast responder. It mobilizes within minutes and uses general tools to attack many threats. Because innate responses often fade within days, they have not been the centerpiece of most vaccine strategies.

Pulendran’s group focused on the innate system’s range. “What’s remarkable about the innate system is that it can protect against a broad range of different microbes,” Pulendran said. In the study’s framing, innate immunity can look almost universal, but usually only briefly.

Hints of longer-lasting, broad protection exist. Epidemiological and clinical studies of live vaccines, including the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) tuberculosis vaccine, have suggested some non-specific protection against unrelated infections. But those effects have been variable, and the biology has been hard to pin down.

Pulendran’s team previously studied BCG in mice and found a lung-based feedback loop. T cells recruited as part of the adaptive response sent signals that kept innate cells active far longer than usual. “Those T cells were providing a critical signal to keep the activation of the innate system, which typically lasts for a few days or a week, but in this case, it could last for three months,” Pulendran said.

The new work tries to build that loop on purpose, using an intranasal vaccine.

The vaccine is described in the study as GLA-3M-052-LS + OVA. It combines two immune stimulants, a TLR4 agonist called GLA and a TLR7/8 agonist called 3M-052-LS, along with a harmless antigen, ovalbumin (OVA), an egg protein. In the paper’s logic, the TLR agonists act as a strong “danger” signal for innate cells, while the antigen helps recruit and anchor T cells in the lungs so the signal does not fade quickly.

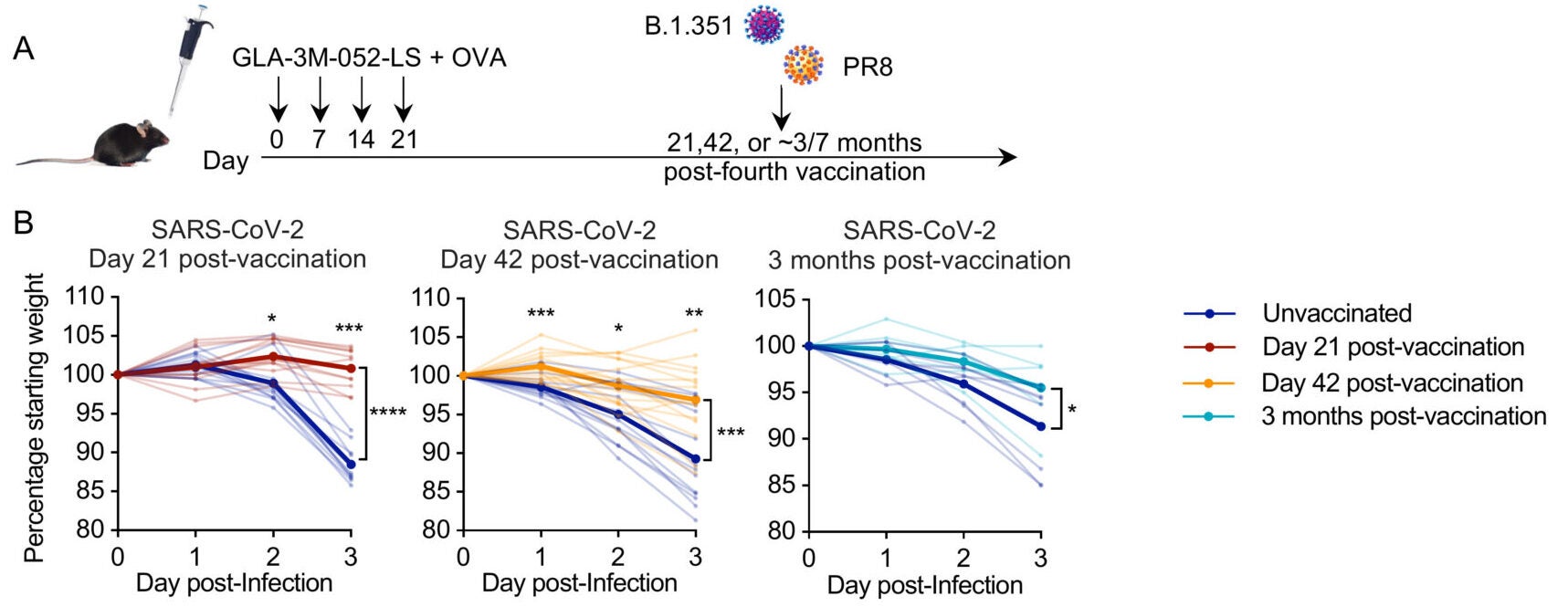

Mice received intranasal doses, with the study describing a four-dose schedule. The paper also reports that three to four immunizations were sufficient for protection in some challenges. After vaccination, researchers exposed mice to different respiratory threats at multiple time points, including weeks later and about three months later.

With SARS-CoV-2 challenge at 21 days, 42 days, and three months after vaccination, vaccinated mice showed much less weight loss than unvaccinated mice. The study also reports reduced viral measures in the lungs and less lung inflammation and damage in vaccinated animals. The team also reports cross-protection against SARS-CoV MA15 and SCH014 MA15.

The researchers broadened the test. Vaccinated mice showed durable protection against bacterial infection with Staphylococcus aureus and Acinetobacter baumannii, measured by lower lung bacterial loads, including at about three months post-vaccination. The study also assessed protection against an intravenous S. aureus infection and reported lower kidney bacterial load and less weight loss in immunized mice than in unvaccinated mice.

Then the question shifted from infections to irritants. “Then we thought, ‘What else could go in the lung?’” Pulendran said. “Allergens.” In a house dust mite asthma model, unvaccinated mice showed a strong Th2-type allergic response and mucus in the airways.

Vaccinated mice had reduced features of allergic inflammation, including lower serum IgE in the reported results, and clearer airways. Those effects persisted for at least three months in the study’s experiments.

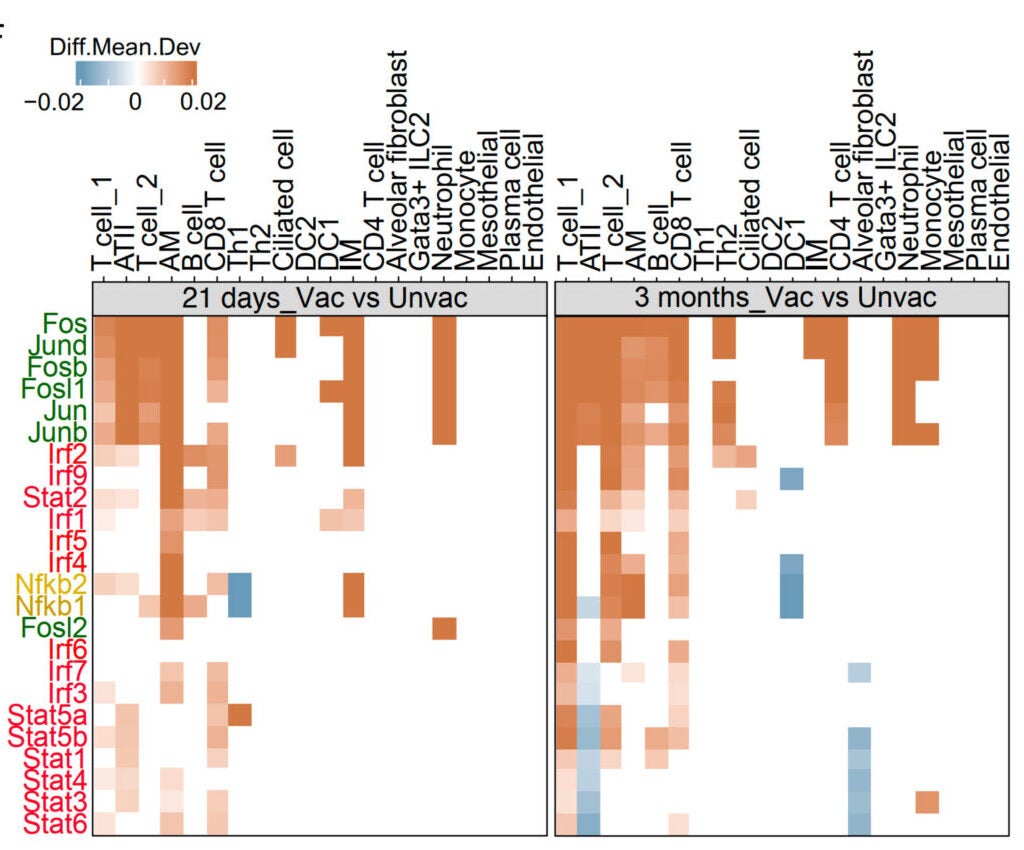

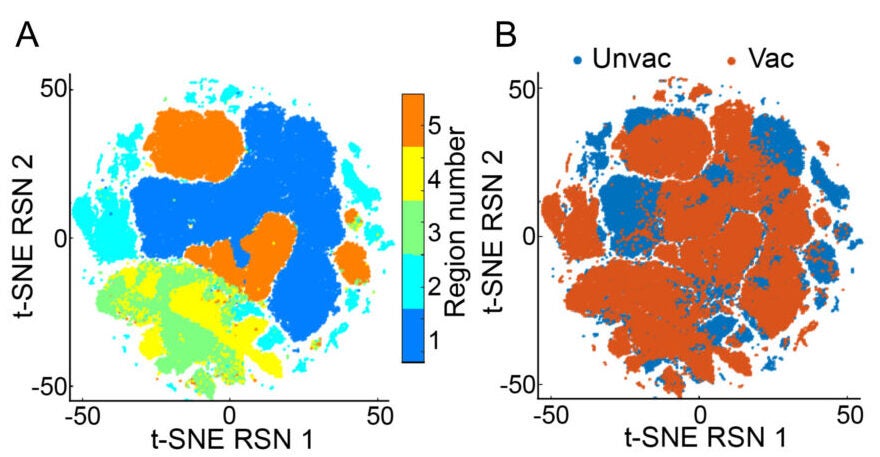

The paper describes long-lived, antigen-specific T cells in the lungs after vaccination, including tissue-resident memory T cells. It also reports sustained activation changes in alveolar macrophages, the lung’s resident “cleanup” immune cells, including signs of persistent reprogramming. The study links protection to a networked response in the lung, involving innate immune cells, T cells, and structural lung cells, a concept the authors call “integrated organ immunity.”

Mechanistically, the study tests dependencies. Removing both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during the immunization regimen eliminated protection against SARS-CoV-2 and against S. aureus bacterial burden in the reported experiments. The paper also reports that blocking RANKL during immunizations eliminated protection in the challenges they tested, while pharmacological inhibition of CD40L, IFN-γ, or TNF-α signaling did not.

The authors also flag open questions. They write that the relative contributions of circulating memory T cells versus tissue-resident memory T cells remain to be determined. They also highlight translation limits: the work is in mice, and human mucosal immunity is shaped by lifelong exposures. The discussion argues that controlled human infection studies would be essential to evaluate this approach in “immunologically experienced humans.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

The original story “New nasal vaccine protects lungs for months against viruses, bacteria, and allergens” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New nasal vaccine protects lungs for months against viruses, bacteria, and allergens appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.