Scientists have discovered a single-celled organism in the hot springs of Lassen Volcanic National Park, which is not only the first eukaryote to grow at 63 degrees Celsius (approximately 145 degrees Fahrenheit) but also the highest temperature for any eukaryote.

Scientists had previously assumed that no eukaryotic life could survive temperatures above approximately 60 degrees Celsius; any higher temperature would cause the proteins and membranes necessary for life to break down. However, the discovery of this single-celled organism proves that there is a possible ceiling for the temperature at which eukaryotic life may survive.

H. Beryl Rappaport and Angela Oliverio of Syracuse University in New York told The Brighter Side of News, “Our findings challenge long-held temperature limits for eukaryotic cells and expand our view of where this kind of life can survive.”

The organism was isolated from geothermal springs found in tributaries of Hot Springs Creek, located in Northern California. The research team conducted research over a three-year period, sampling 20 separate sites where the water temperature was about 65 degrees Celsius.

The samples were found to contain filamentous or woolly-like groups of heat-adapted microbes, and upon further analysis of the samples for enhancing the growth of bacteria, the research team found a previously unknown species of amoeba that thrived in water at temperatures of 57 to 63 degrees Celsius.

In naming the species Incendiamoeba cascadensis, the research team indicated that the new species inhabits an environment associated with fire and it has its origins in an area of the Cascade Range of Mountains.

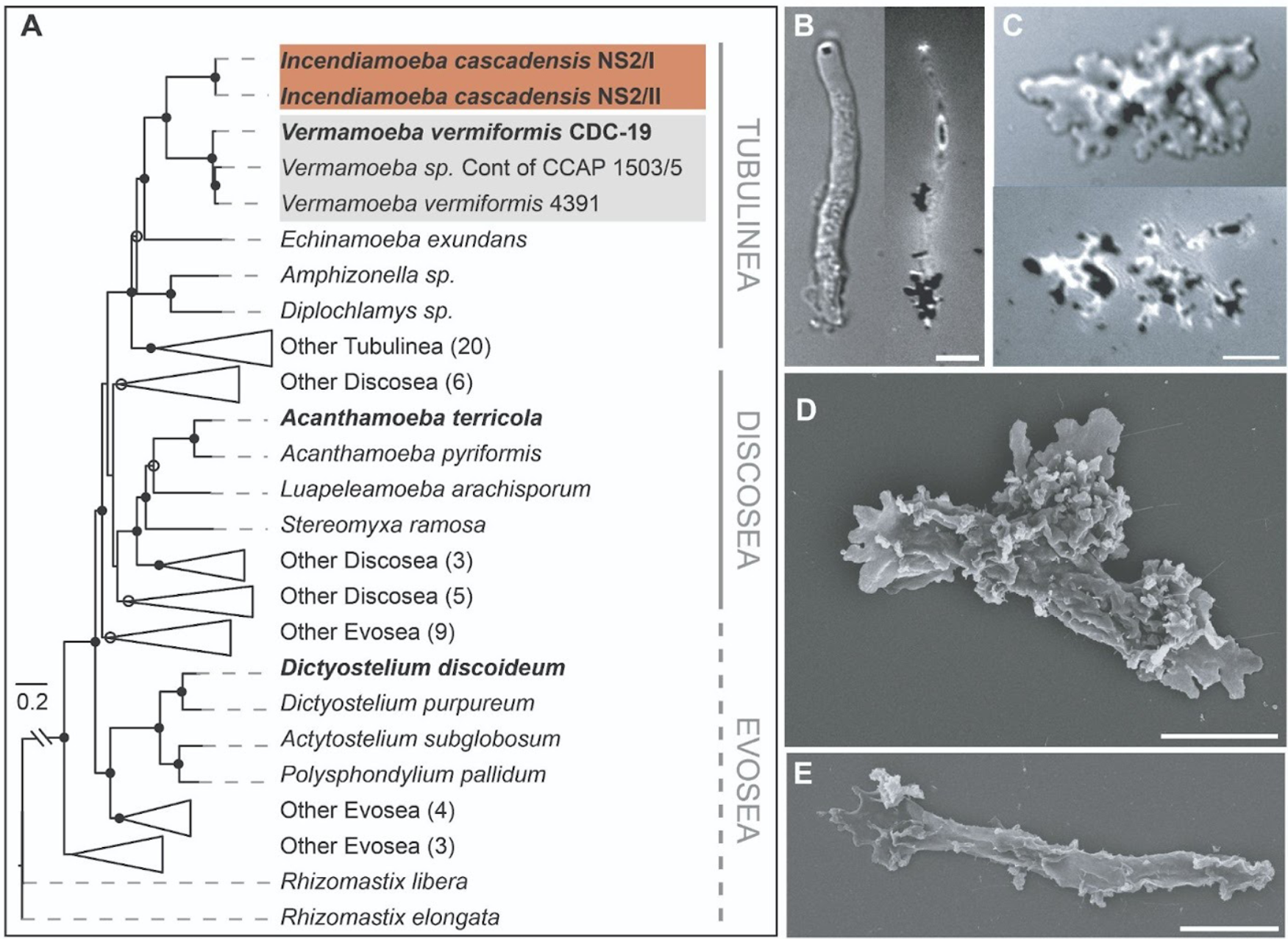

Based on genetic analysis, the organism belongs to a larger group of amoebas called Tubulinea, and it is genetically most closely related to the ameboid species known as Vermamoeba vermiformis, but it is quite distinct from it. This amoeba relies on high temperatures, while most of the organisms in its family (i.e., related amoebas) prefer the cooler room temperature range, and do not survive consistently over the range of 40-45 degrees Celsius.

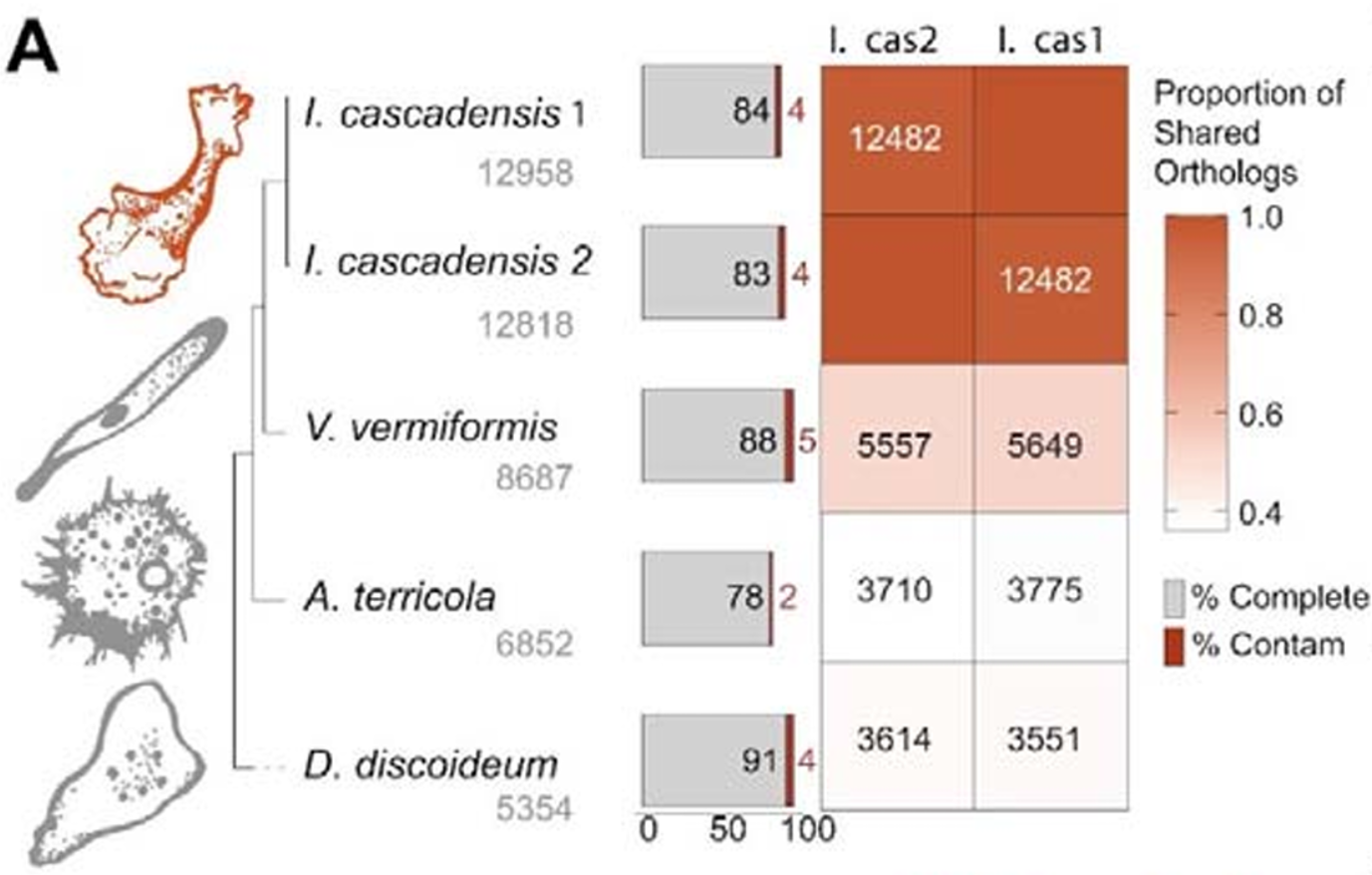

The researchers utilized two nearly complete genomes as a means to position this newly identified organism on the tree of life, comparing these genomes with other ameboid organisms. They found a unique lineage, or a unique branch as part of the greater tree of life, within the subgroup Echinamoebida.

It was determined that the Echinamoebida 18S rRNA gene had only a 94 percent similarity with that of the ameboid organism Vermamoeba vermiformis, which is considerably less than what would normally be expected for organisms of the same genus, indicating that both of these amoebas were likely to require separation into new genera and species.

During their investigation of more than 31,000 publicly available environmental DNA datasets, the investigators also found many matching sequences in geothermal microbial mats from New Zealand, and several closely related sequences from areas of Yellowstone National Park; all of the sequence matches came from geothermal environments.

Therefore, the investigators proposed that the new organism represented a genetically unique but highly specialized organism that exists in geothermal ecosystems, as opposed to the vast majority of eukaryotic organisms, and therefore is likely to have a global distribution. Thus, the investigators concluded that the new organism lives at the extreme or at the edges of boiling temperatures.

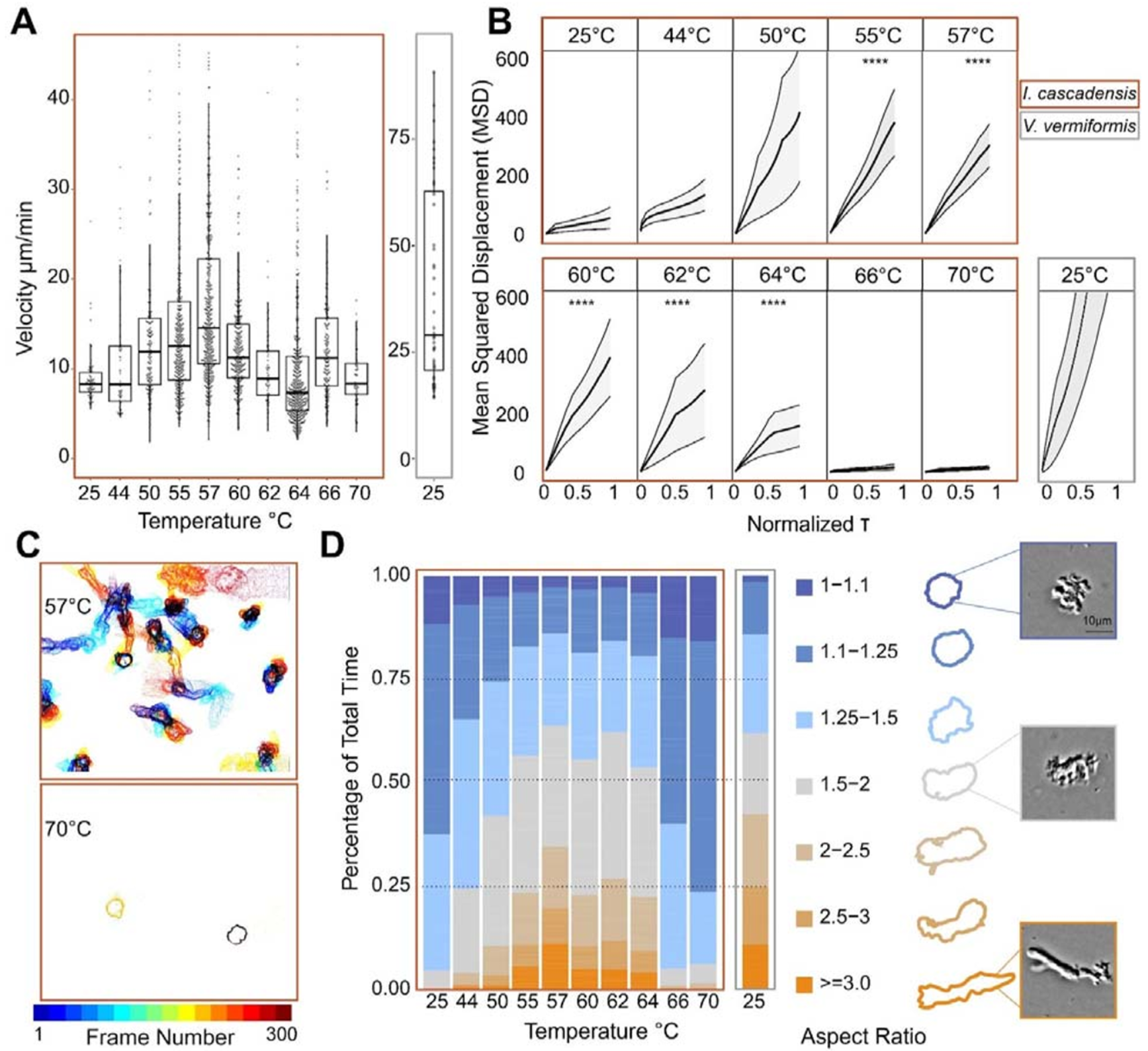

Under microscopic observation, Incendiamoeba cascadensis occurs in two primary morphologies: the elongated or worm-like form is adapted to moving quickly, while the rounded or short form is adapted to feeding and probing. As temperatures exceed approximately 64 degrees, the amoeba form a cyst or protective spherical shell that varies in diameter from 5 to 15 micrometers, which permits the organism to survive short-term exposure to temperatures that would otherwise be fatal.

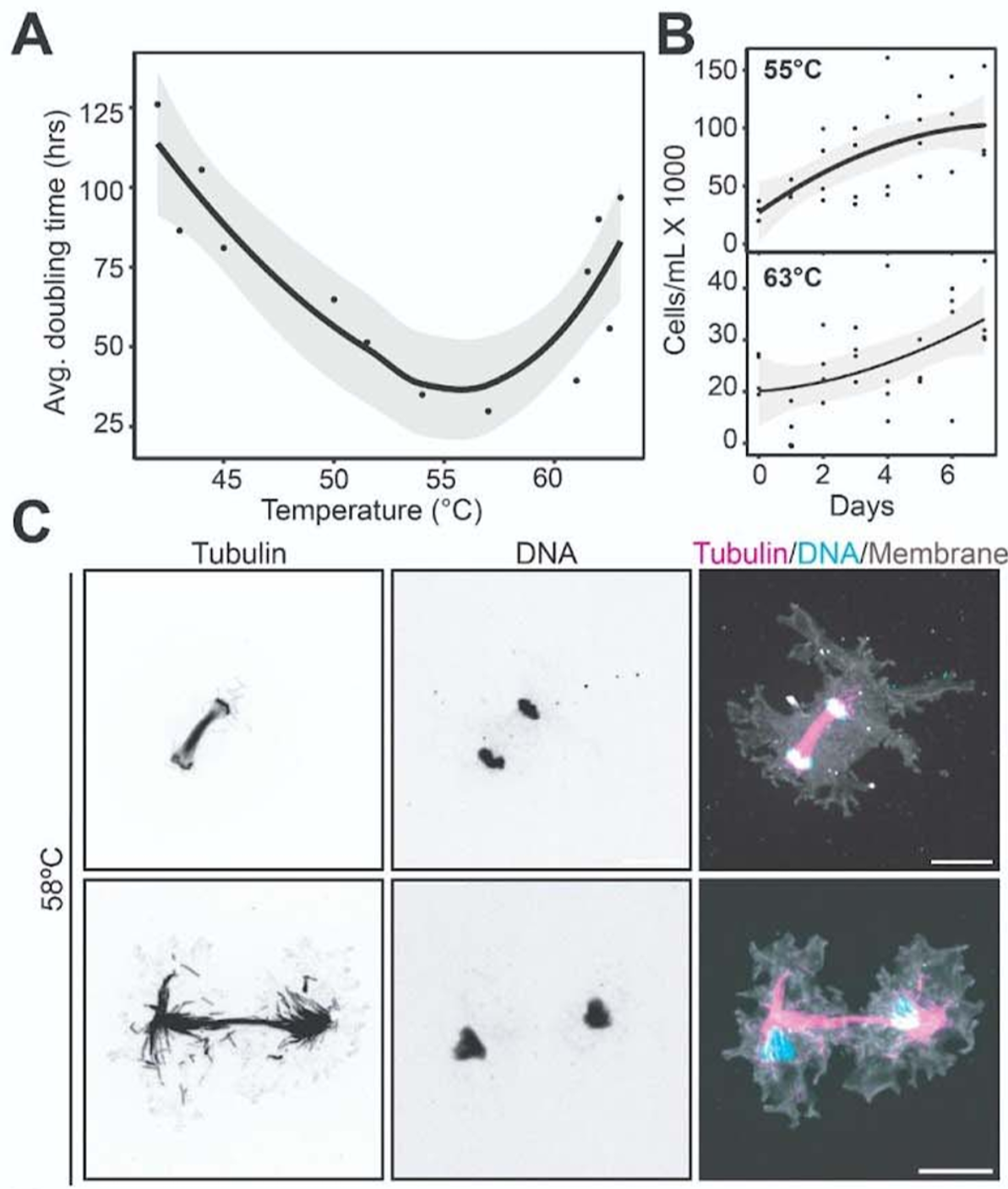

Growth experiments tested Incendiamoeba cascadensis at each of the 17 temperatures from 30-64 degrees Celsius. An Obligate Thermophile, Thermoplasma volcanium (T. volcanium) does not grow below the temperature of 42 degrees Celsius, but thrives at temperatures ranging between 55 and 57 degrees Celsius. The most remarkable characteristic of T. volcanium is that the growth rate at 63 degrees Celsius outpaces that of Echinamoeba thermarum (E. thermarum), which is the other record-holding eukaryote for growth at this extreme.

Advanced imaging allowed researchers to observe the process of mitotic cell division taking place at these extreme temperatures. Researchers discovered that during this process, all phases, including metaphase and anaphase, are completed at a temperature of 63 degrees Celsius.

Comparison of the mitotic mechanisms in T. volcanium and other amoebae revealed that even though there are similarities, it is possible that structural variations between the two groups of organisms allow T. volcanium to grow effectively in extreme heat conditions.

Advanced imaging was also used to visualize the crawling mechanism in T. volcanium. At optimum temperatures, T. volcanium has been observed to crawl at approximately 14.5 micrometers per minute. T. volcanium decreased crawling speeds as temperature decreased, but continued to be active until temperatures reached 64 degrees Celsius.

At 70 degrees Celsius, amoebae have been observed to cease movement and form cysts; however, many were able to be revived when temperatures returned to 60 degrees Celsius. Conversely, a temperature of 80 degrees Celsius was determined to be lethal.

Thermoplasma volcanium has the ability to change from one body shape to another with a frequency of approximately every ninety seconds at 57 degrees Celsius. The ability to alternate between body shapes quickly is advantageous because it allows T. volcanium to adapt to both fast-moving and slow-moving environments, given that temperature can change drastically over short distances (e.g., from one centimeter to another).

T. volcanium ingests filamentous bacteria found in environments with an approximate temperature of 60 degrees Celsius, such as Meiothermus ruber. Incendiamoeba cascadensis is an amoeba that encircles the bacterial threads, pulling them in and sometimes even contorting them into tight loops. By exploiting a food source that no other eukaryotes can access, it employs the strategy of abducting its prey at will.

“To understand how Incendiamoeba cascadensis withstands such extreme temperatures, we assembled its genome and compared it to related species. We found the genome to be approximately 48 million base pairs long, with a GC content of 36 percent. This makes it slightly larger and less GC-rich than that of Vermamoeba vermiformis,” Rappaport explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“In addition, our team was able to assemble the mitochondrial genome, which consists of approximately 53,000 base pairs,” she continued.

The genome contains a large number of enzymes and pathways associated with the rapid signaling of molecules, e.g., pathways such as calcium signaling, MAP kinase signaling, and Ras signaling. These enzymes aid in the detection and rapid response to rapid changes in the surrounding environment—crucial skills for survival in volatile geothermal streams. In addition, the amoeba has an expanded suite of genes involved in the maintenance of protein function (proteostasis).

The extensive repertoire includes heat shock proteins and chaperones (i.e., small heat shock proteins, HSPA5) that mitigate against protein misfolding (unraveled) due to damage caused under extreme temperatures. The amoeba has a much larger set of genes related to repairing and recycling damaged proteins and repairing damaged DNA.

Protein melting temperatures and average melting temperatures of proteins within Incendiamoeba cascadensis were predicted to be significantly higher than those of their relatives. The majority of proteins were predicted to remain stable above 60 degrees Celsius. Enhanced surface charges of these proteins likely help maintain structural integrity through enhanced interactions between internal portions of the proteins.

The discovery of Incendiamoeba cascadensis shows that amoebae, not just fungi and algae, are capable of colonizing habitats close to the boiling point of water. The discovery indicates the potential for the existence of other heat-tolerant eukaryotic organisms residing in extreme environments that have yet to be fully explored and understood.

The finding not only alters how we view the ability of complex cells to adapt to environmental change on Earth, but also serves as an invaluable resource in looking for life on other planets.

Understanding how Incendiamoeba cascadensis survives extreme temperatures may be instrumental in designing heat-stable proteins and enzymes for medical, industrial and biotechnological applications, ranging from developing detergents to enabling improvements in industrial chemical processes.

As well, the discovery potentially widens the spectrum of habitable environments, which in turn is likely to shape the search for extraterrestrial life and the field of astrobiology.

Research findings are available online in the journal bioRxiv.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post A heat-loving amoeba smashes the temperature record for complex life appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.