Talking to yourself feels deeply human. Inner speech helps you plan, reflect, and solve problems without saying a word. New research suggests that this habit may also help machines learn more like you do.

Scientists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan report that artificial intelligence systems perform better when they are trained to engage in a form of inner speech. The study, published in the journal Neural Computation, shows that AI models can learn faster and adapt to new tasks more easily when they combine short-term memory with self-directed internal language.

The work was led by Dr. Jeffrey Queißer, a staff scientist in OIST’s Cognitive Neurorobotics Research Unit. His team focuses on understanding how learning works in both brains and machines, then using those insights to improve artificial systems.

“This study highlights the importance of self-interactions in how we learn,” Queißer says. “By structuring training data in a way that teaches our system to talk to itself, we show that learning is shaped not only by the architecture of our AI systems, but by the interaction dynamics embedded within our training procedures.”

Humans switch tasks with ease. You can follow spoken directions, solve a puzzle, then cook dinner without retraining your brain. For AI systems, this kind of flexibility remains difficult.

“Most AI models excel only at tasks they have seen before. When conditions change, performance often drops. Our team studies what we call content-agnostic processing, which allows a system to apply learned rules across many situations,” Queißer told The Brighter Side of News.

“Rapid task switching and solving unfamiliar problems is something we humans do easily every day. But for AI, it’s much more challenging,” Queißer added.

To tackle this problem, the researchers drew ideas from developmental neuroscience, psychology, robotics, and machine learning. The goal was not just to improve performance, but to understand why certain designs work better.

The team first looked at working memory, the short-term system that lets you hold and manipulate information. You rely on it when doing mental math or recalling instructions.

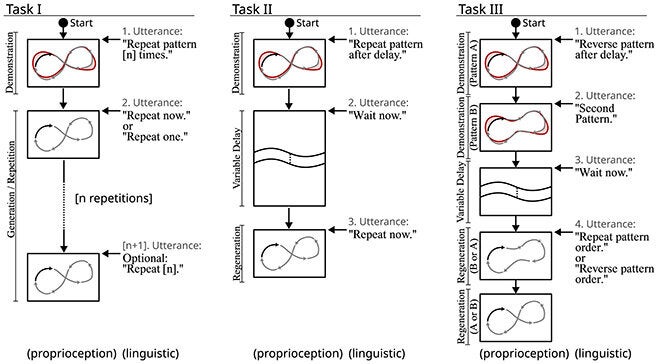

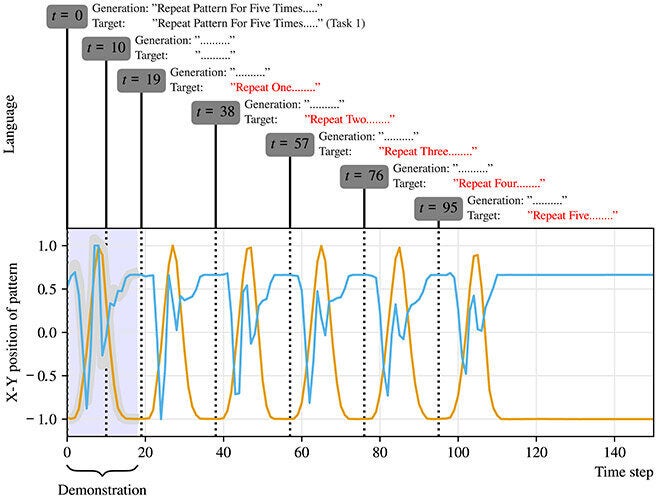

In their simulations, the researchers tested AI models on pattern-based tasks that required holding information briefly, then transforming it. Some tasks asked the system to reverse a sequence, while others required recreating a pattern after a delay.

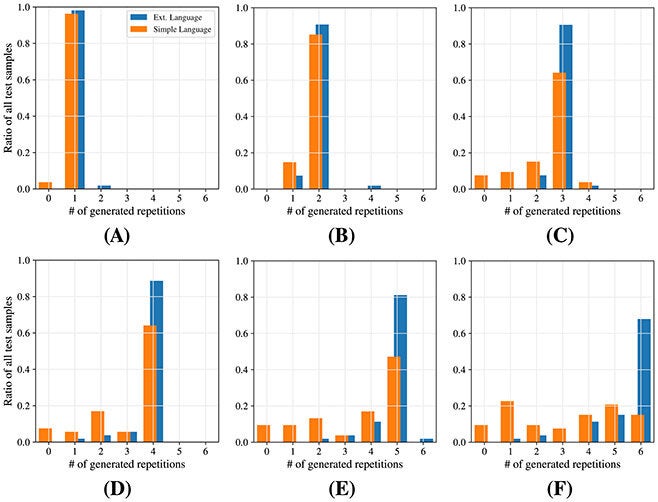

Models that used multiple working memory slots performed better than those with only one or none. These slots acted as temporary containers for information, allowing the system to separate what it was storing from how it used that information.

This design helped the AI handle more complex tasks, but the biggest gains came when another feature was added.

The researchers introduced what they call self-directed inner speech. During training, the AI was encouraged to generate internal language-like signals, described by the team as “mumbling,” while it worked through tasks.

These internal signals did not communicate with users. Instead, they allowed the system to guide its own behavior step by step.

When combined with multiple working memory modules, inner speech led to stronger performance, especially during multitasking and long sequences of actions. The AI also showed improved ability to generalize when faced with new task combinations.

“Our combined system is particularly exciting because it can work with sparse data instead of the extensive data sets usually required to train such models for generalization,” Queißer says. “It provides a complementary, lightweight alternative.”

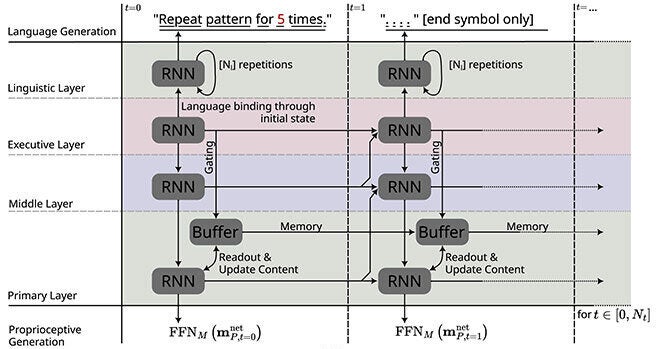

The simulations relied on a stacked recurrent neural network paired with several working memory modules. Tasks were presented as temporal patterns followed by language-based goals.

Training used a supervised approach that minimized free energy, while task execution followed the active inference framework. Under optimal conditions, a clear hierarchy emerged inside the network, with different layers handling timing, memory, and control.

The researchers found that inner speech helped separate content from control. Memory modules stored information, while self-generated language guided how that information was used. This structure supported learning across tasks that the system had never seen before.

The current study took place in a controlled simulation environment. The next step involves adding more realism.

“In the real world, we’re making decisions and solving problems in complex, noisy, dynamic environments,” Queißer says. “To better mirror human developmental learning, we need to account for these external factors.”

Understanding how inner speech supports learning may also shed light on human cognition. By modeling these processes in machines, researchers can test theories about how the brain organizes thought and action.

“We gain fundamental new insights into human biology and behavior,” Queißer says. “We can also apply this knowledge, for example in developing household or agricultural robots which can function in our complex, dynamic worlds.”

This work points toward AI systems that learn with less data and adapt more flexibly. Such systems could reduce the cost and energy demands of training large models. Robots guided by internal language and memory may handle unpredictable environments more safely and efficiently.

The findings may also influence neuroscience by offering testable models of inner speech and working memory. Over time, this cross-talk between biology and engineering could lead to smarter machines and a deeper understanding of how people learn.

Research findings are available online in the journal Neural Computation.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post AI systems learn better when trained with inner speech like humans appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.