Most of the time, you assume your brain is either “on” or “off,” awake or asleep. A new study shows something far more intricate. Deep inside the skull, entire networks of cells quietly hand off control across the day, like shifts of workers trading places on a factory floor.

An international team led by the University of Michigan has mapped which parts of the brain are active at different times of day, down to the level of single cells, in mice. Their work offers a rare, global view of how activity moves through the brain as animals wake, stay up, and finally sleep.

The project started with a deceptively simple goal: understand fatigue. Senior author Daniel Forger, a professor of mathematics at Michigan, and his colleagues wanted to see how the brain changes as wakefulness drags on and how sleep resets those changes.

“We’re seeing profound changes in the brain over the course of the day as we stay awake and they seem to be corrected as we go to sleep,” Forger said.

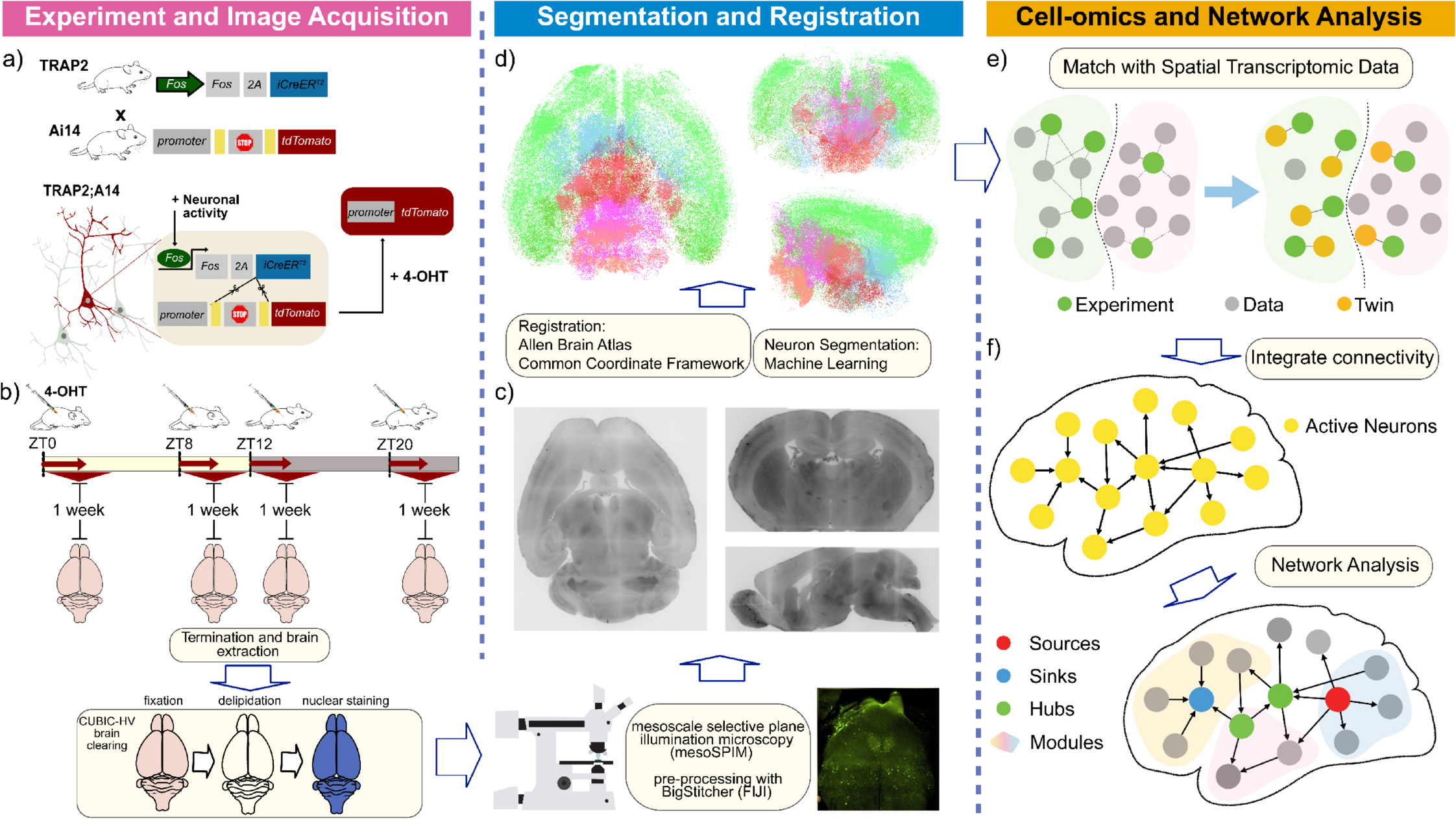

To capture those shifts, the team used mice as a stand-in for humans. Researchers in Japan and Switzerland developed an experimental system that makes active neurons glow. They used a genetic tagging method so that when a neuron fired, it produced a fluorescent signal that stayed behind as a marker.

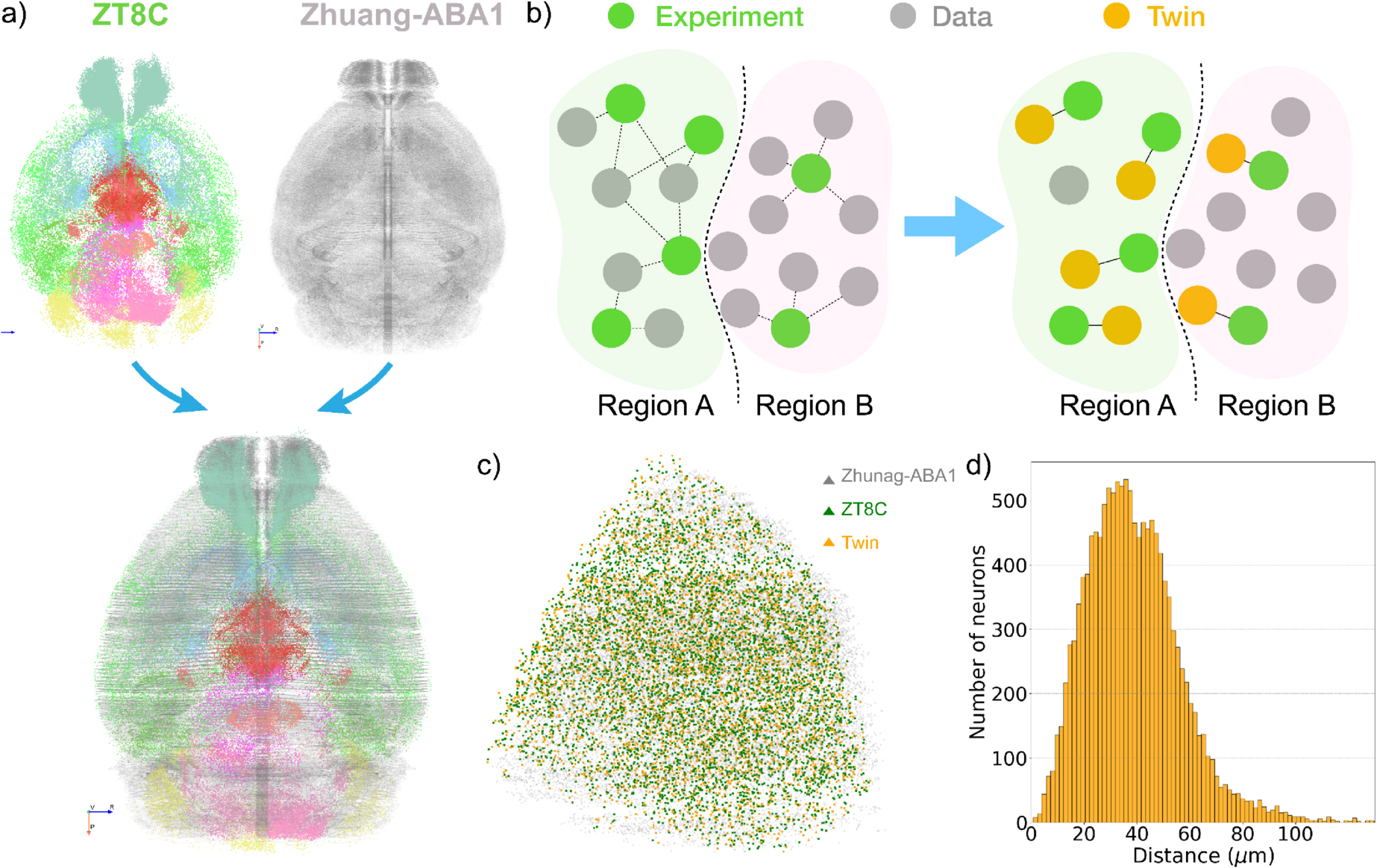

Then they turned to light sheet microscopy, a cutting-edge imaging technique. This method let them build three-dimensional images of whole mouse brains, with single glowing cells visible throughout. Instead of sampling a small slice of tissue, they could see which cells were active across the whole brain at different times of day.

Beautiful images alone were not enough. The Michigan group built mathematical and computational workflows to turn those glowing points into data that could be analyzed.

They registered each brain to a reference atlas, so the same region could be compared across animals and time points. Then they counted active neurons in many structures and asked how those patterns changed across the waking and sleeping cycle.

“The mathematics behind this problem are actually quite simple,” said co-author Guanhua Sun, who worked on the project as a doctoral student at Michigan and now teaches at New York University. The hard part, he said, was combining new data with older mouse brain datasets in a way that stayed faithful to known biology.

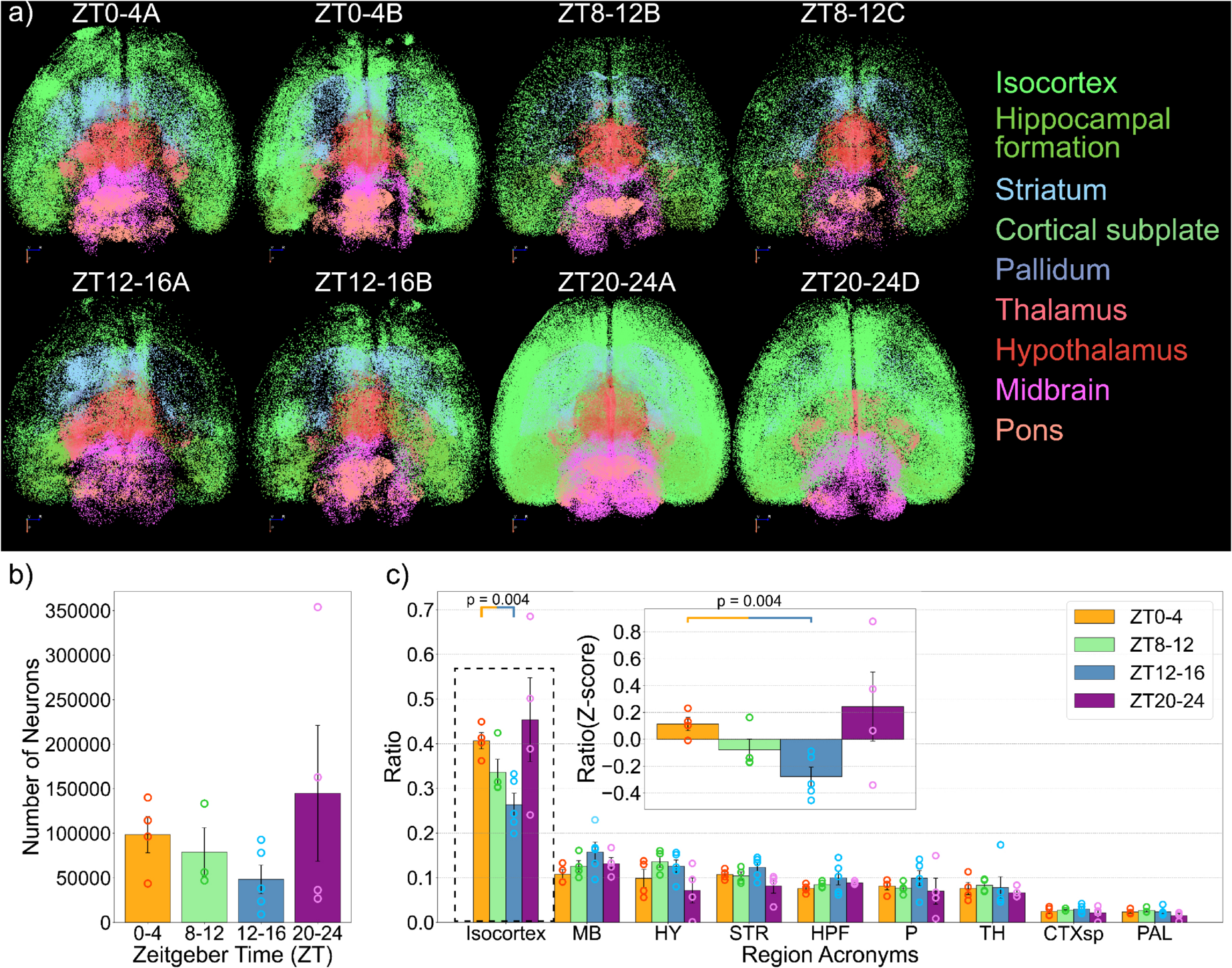

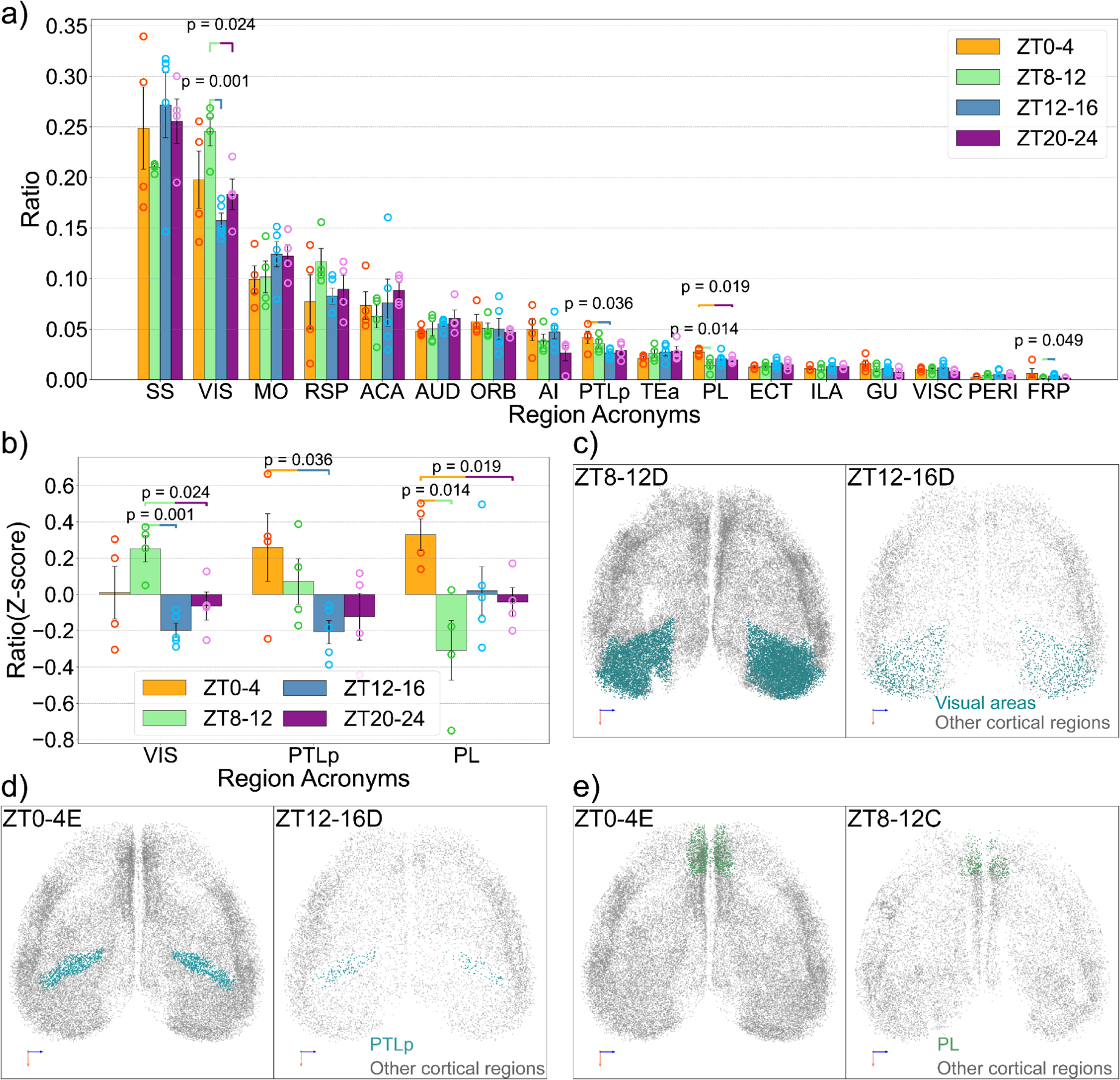

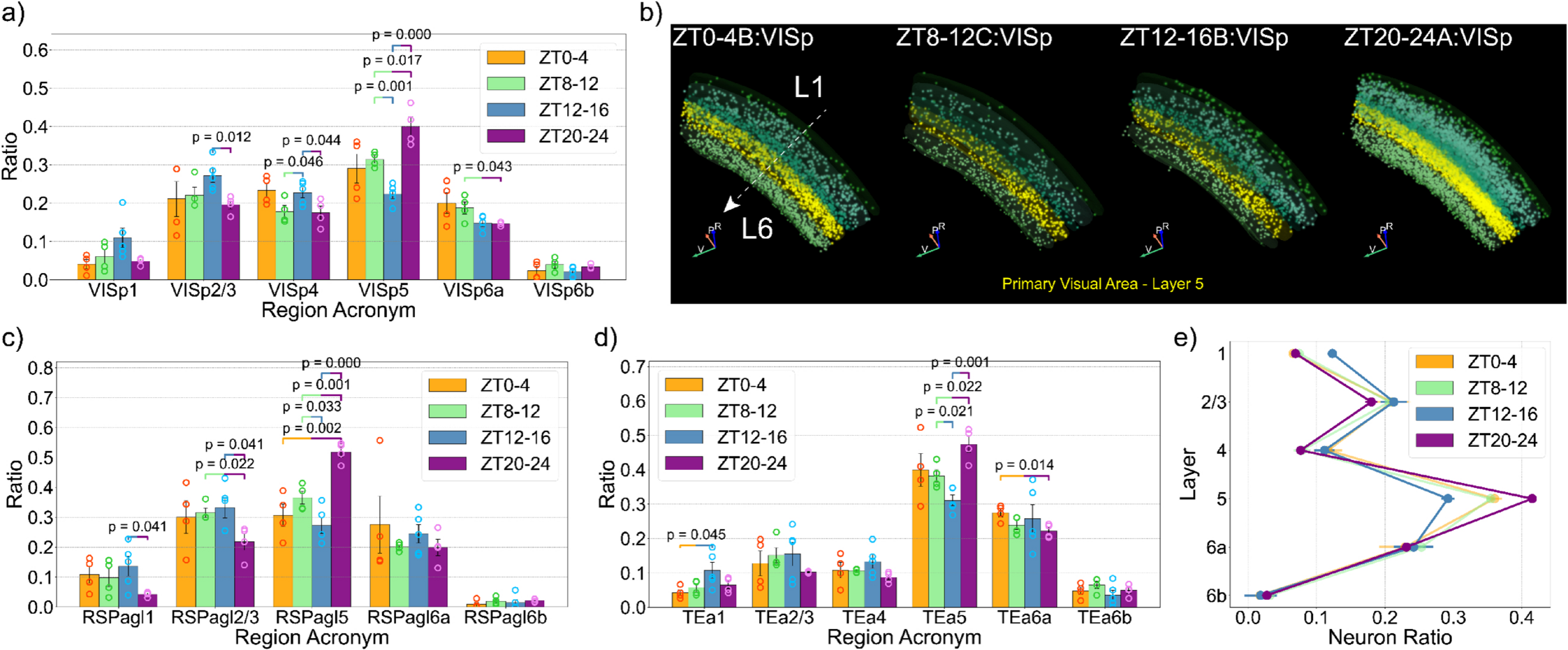

Once the pieces fit together, a clear pattern emerged: as mice woke up, activity first rose in inner, subcortical regions. As their active period continued, hubs of activity gradually shifted outward to the cortex, the folded surface layer linked to thought and planning.

The team did not only count cells. They also asked how different brain regions formed networks at each time of day. By looking at which active areas connect to which others, they could identify “hubs” that seemed to coordinate communication.

Study co-author Konstantinos Kompotis, a senior scientist at the Human Sleep Psychopharmacology Laboratory at the University of Zurich, compared it to changing traffic patterns.

“The brain doesn’t just change how active it is throughout the day or during a specific behavior,” he said. “It actually reorganizes which networks or communicating regions are in charge, much like a city’s roads serve different traffic networks at different times.”

Early in the waking period, subcortical systems, which help control arousal and basic drives, took the lead. As time passed, control shifted toward cortical regions on the brain’s surface. By the end of the active phase, large-scale cortical networks dominated.

That kind of reorganization suggests that fatigue is not just a feeling of being tired. It reflects deep changes in which brain systems are carrying the load.

Forger’s group hopes that the patterns they see can eventually translate into tools for people whose performance matters in life-or-death situations.

“We’re actually terrible judges of our own fatigue. It’s based on our subjective tiredness,” Forger said. “Our hope is that we can develop ‘signatures’ that will tell us if people are particularly fatigued, and whether they can do their jobs safely.”

Right now, the experimental tagging and light sheet imaging work only in animal models. You cannot clear a human brain and place it under a microscope. But the analysis framework is flexible, Sun said.

The same mathematical ideas could be adapted to human data from EEG, PET or MRI scans, which measure activity more crudely but across the whole brain. With careful work, it might be possible to identify comparable network shifts in people as they stay awake, become exhausted, and then recover with sleep.

Kompotis has already started teaming up with industry partners to use the new techniques in drug research. By watching how experimental compounds change the glowing activity patterns in mouse brains, he hopes to see how candidate drugs affect sleep, alertness, or other brain states.

“The method opens the door for us to study conditions far beyond everyday tiredness. The patterns we found across regions may matter for understanding psychiatric disorders, though this study did not directly test that idea,” Forger told The Brighter Side of News.

Because the framework can be adapted to other animals and other kinds of data, researchers could apply it to models of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or other brain disorders. That flexibility, Sun said, is one of the most important strengths of the approach.

“The way we detect human brain activity is more coarse-grained than what we see in our study,” he said. “But the method we introduced in this paper can be modified in a way that applies to that human data. You could also adapt it for other animal models, for example, that are being used to study Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. I would say it’s quite transferable.”

The study depended on international collaboration supported by the Human Frontier Science Program, along with funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation and the U.S. Army Research Office. Teams in Michigan, Zurich, and Japan each contributed pieces that none could have built alone.

The Japanese group, led by Hiroki Ueda at the RIKEN Center for Biosystems and Dynamics Research, developed key parts of the experimental approach. The Zurich team helped connect the findings to sleep science and real-world questions of tiredness and performance.

The paper carries a dedication that reflects how personal scientific work can become. The team honors Steven Brown, a professor and section leader for chronobiology and sleep research at the University of Zurich, who died in a plane crash during the project.

“Steve was a perfect collaborator,” Forger said.

Kompotis echoed that feeling. “We learned how important one person can be in scientific research, be it in brainstorming or in bridging ideas and concepts. Steve was a core element of this collaboration,” he said. “It is yet another reason for us to be very proud of this story.”

In the end, the study offers something rare: a moving picture of the brain across a full day, at single-cell resolution. It shows a living organ that constantly hands off control from one set of networks to another, quietly adjusting to the demands of wakefulness and the reset of sleep.

This work lays the groundwork for objective measures of fatigue. By identifying “signatures” of brain activity that track how long an animal has been awake, researchers move closer to tools that can assess tiredness without asking people how they feel.

In high-risk jobs, such as aviation or surgery, those signatures could guide scheduling or safety checks. Instead of relying on self-report, employers might one day use brain-based measures, derived from EEG or MRI, to confirm that a pilot or surgeon is fit to perform.

The same framework can help test medicines that act on sleep and alertness. Industrial partners already work with the team to see how drug candidates reshape activity patterns. That could speed development of better treatments for sleep disorders or conditions that cause daytime fatigue.

Because the computational method is adaptable, it could also support research on neurodegenerative diseases or mental illness. By comparing healthy activity networks with those altered in disease models, scientists may pinpoint network-level changes that need to be targeted by new therapies.

At a broader level, the study shows the value of linking detailed cellular data with large-scale networks. That kind of approach will likely become more common as neuroscience moves toward whole-brain, whole-day views of function. It may change how clinicians think about brain health, shifting focus from static images to dynamic patterns that unfold over time.

Research findings are available online in the journal PLOS Biology.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post All day brain tracking helps scientists finally decode fatigue appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.