The social fabric of Iron Age Britain, spanning roughly from 800 BC to AD 100, has long puzzled historians and archaeologists. Recent breakthroughs in genetic analysis are now shedding light on the lives and social structures of these ancient communities.

A unique burial site in Dorset has revealed a society centered on matrilineal descent, a rarity in both ancient and modern contexts. This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about gender roles and societal organization in prehistoric Europe.

Iron Age burial customs in southern England offer a glimpse into a society where women held significant power. Genetic analysis of 57 ancient genomes from Dorset’s Durotriges tribe reveals a community predominantly organized around female-line descent.

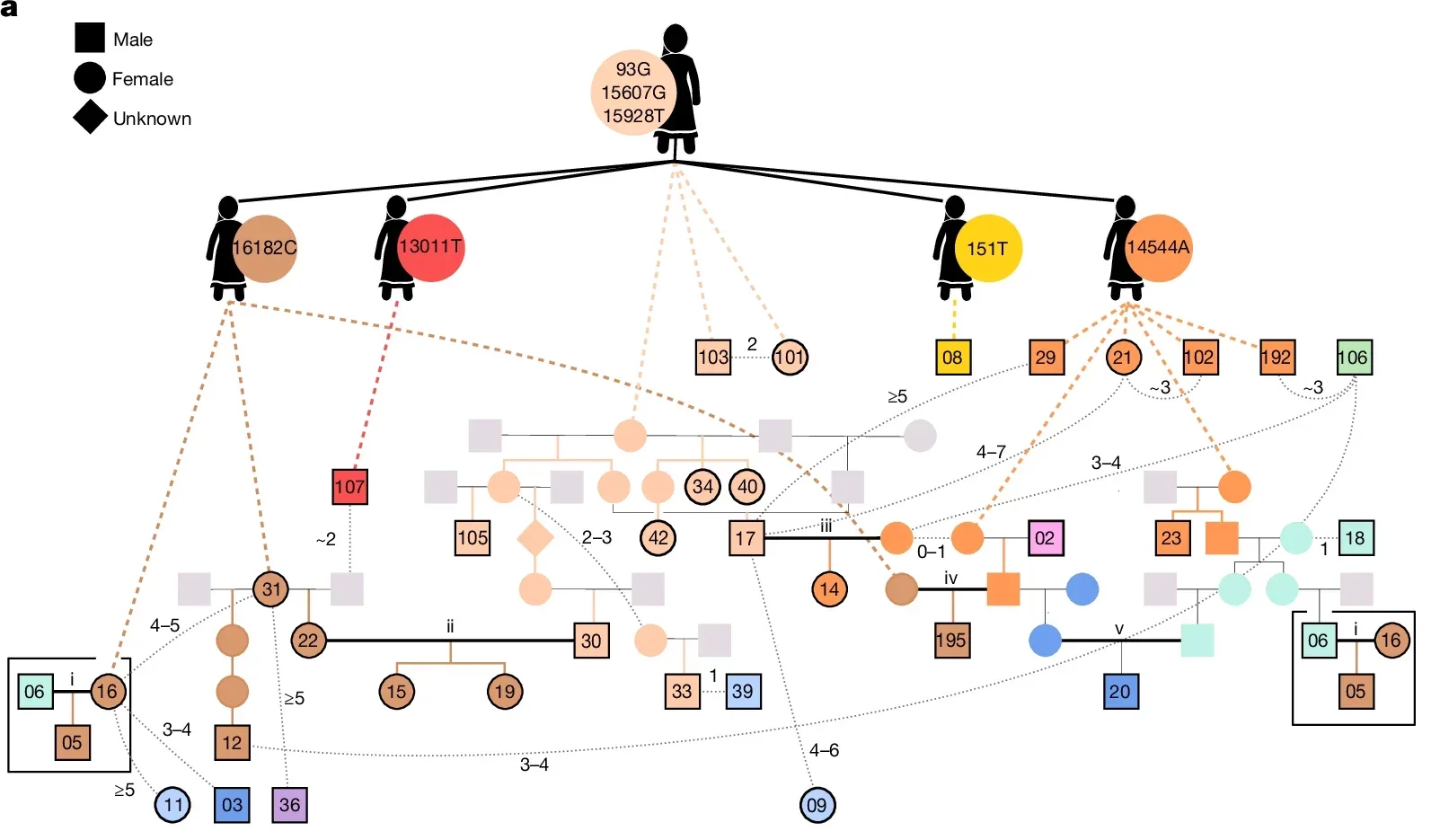

Researchers reconstructed a family tree with branches tracing back to a single maternal ancestor who lived centuries earlier. Astonishingly, paternal lineage connections were almost absent, suggesting that husbands moved to join their wives’ communities after marriage.

Dr. Lara Cassidy, a geneticist at Trinity College Dublin and lead author of the study published in Nature, noted, “This is the first time this type of system has been documented in European prehistory. It predicts female social and political empowerment, which is relatively rare in modern societies but might have been more common in the past.”

This matrilocal system was not confined to Dorset. Similar patterns emerged across Britain. In Yorkshire, for example, genetic data revealed that a dominant maternal lineage had been established by 400 BC. Dr. Dan Bradley, co-author of the study, remarked, “To our surprise, this phenomenon had deep roots on the island and was widespread.”

The Durotriges tribe’s burial customs further highlight the prominence of women. While Iron Age burials in Britain are generally rare due to practices like cremation and excarnation, the Durotriges used formal cemeteries. These burials, often richly furnished, included a diverse array of grave goods. Remarkably, women’s graves contained more prestigious items than those of men, hinting at a matrifocal society.

Related Stories

Archaeological findings align with Roman accounts of empowered British women. Julius Caesar, writing in the first century BC, noted that British women could have multiple husbands. Meanwhile, queens like Boudica and Cartimandua commanded armies and held significant political power.

Dr. Miles Russell, a co-author and archaeologist at Bournemouth University, commented, “The Romans’ descriptions of British women occupying positions of power align with our findings. Women likely played influential roles in many spheres of Iron Age life.”

The genomic data also provide clues about population movement and cultural exchanges. Genetic variation among Iron Age Britons shows that coastal southern England experienced substantial migration during the Iron Age.

This influx of people aligns with archaeological evidence of cross-channel trade and interaction. Such mobility could explain the introduction or reinforcement of Celtic languages in Britain, a topic of ongoing debate among linguists and historians.

Dr. Cassidy explained, “While migration into Britain during the Bronze Age has been previously documented, our findings highlight significant cross-channel mobility during the Iron Age as well. It’s possible Celtic languages were introduced on more than one occasion.”

The genetic revelations offer a new lens through which to view the lives of Iron Age communities. The burial grounds in Dorset, nicknamed “Duropolis,” have been excavated by Bournemouth University archaeologists since 2009. The site’s exceptional preservation provided a rare opportunity to analyze over 50 ancient genomes from a single community.

Dr. Martin Smith, an anthropologist and co-author, reflected, “These results give us a new way of understanding the burials. Beyond skeletons, we now see individuals as mothers, daughters, and husbands. This insight brings their identities to life and suggests these communities had a deep understanding of their ancestry.”

Intriguingly, multiple marriages occurred between distant branches of the same family, yet close inbreeding was avoided. This practice suggests a society that valued kinship networks while maintaining genetic diversity. The matrilineal focus of these communities likely shaped their identities and social structures, emphasizing the importance of female ancestry.

The discovery of widespread matrilocality in Iron Age Britain challenges the conventional view of ancient European societies as predominantly patrilineal.

Across Europe, patrilocal and patrilineal systems have been the norm in most Neolithic, Copper, and Bronze Age sites. The Durotriges’ matrilocal structure stands as a striking exception, offering insights into alternative social arrangements that might have existed elsewhere but left little trace.

These findings also contribute to the broader narrative of human migration and cultural exchange. The genetic data reveal fine-grained geographical clusters within Britain, with southern coastal regions showing stronger continental links. This pattern suggests a staged and geographically diverse absorption of influences, possibly including the acquisition of Celtic languages and other cultural elements.

The study underscores the value of integrating genetic analysis with archaeological and historical research. By combining these disciplines, researchers can uncover the hidden stories of ancient societies, offering a richer understanding of our shared past.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ancient DNA reveals Iron Age society led by women appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.