Africa has long been known as the cradle of humanity. Fossils, tools and genetics all point there. Yet the deeper story of how the first modern humans lived, moved and mixed has stayed blurry. Too many later migrations layered over the past. Now, ancient DNA from southern Africa cuts through that noise and shows you a long, quiet chapter of human history that lasted for hundreds of thousands of years.

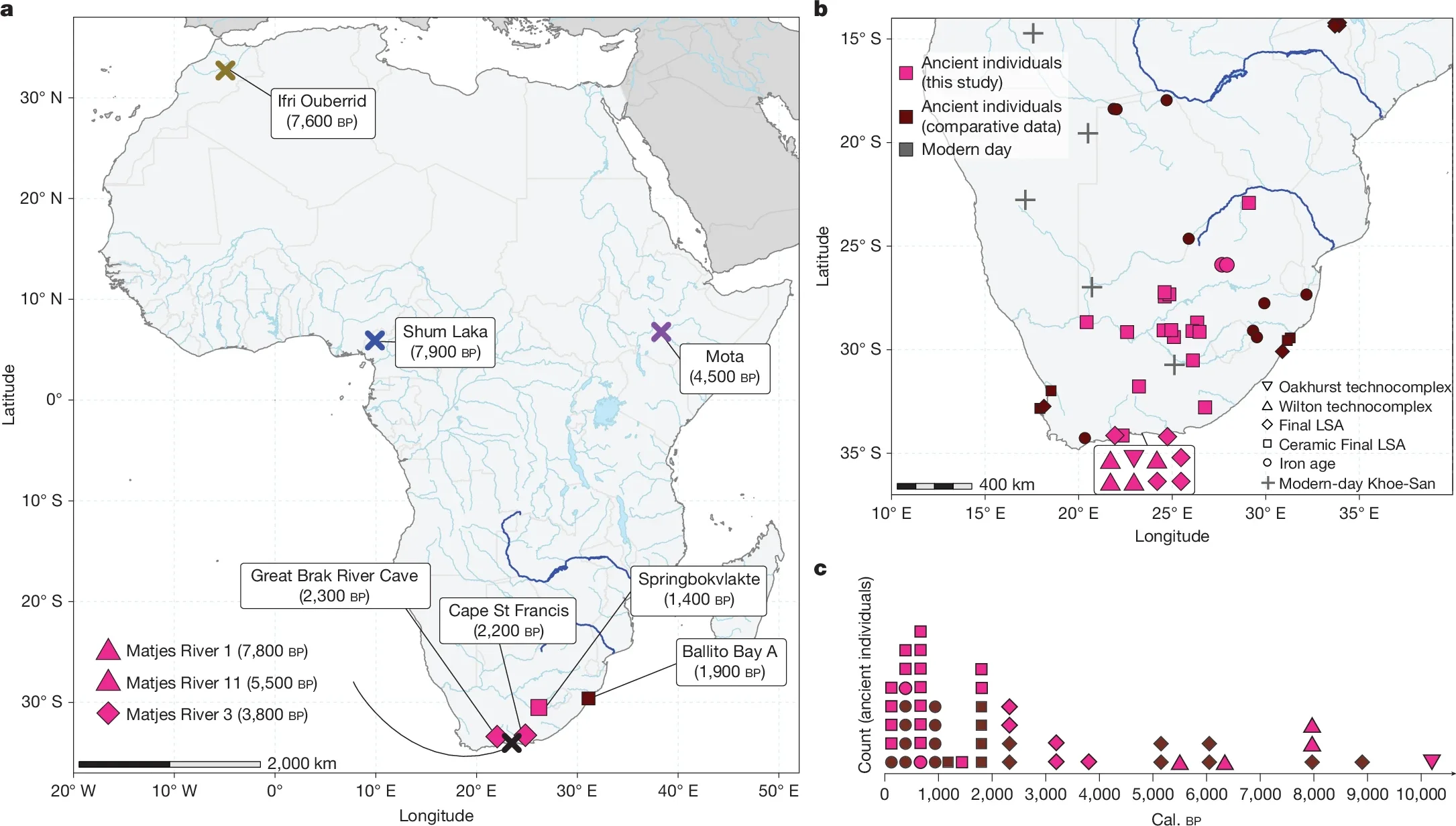

A new study in Nature reports DNA from 28 ancient people who lived south of the Limpopo River in present-day South Africa. Their lives stretch from about 10,200 years ago to roughly 150 years ago. They hunted, gathered, fished and later worked iron. Some were buried near rivers. Others lived along the coast. A large number came from Matjes River, a rocky shelter that held people for nearly 8,000 years.

Researchers sequenced genomes from bones and teeth, then dated them with radiocarbon tests and traced diets with chemical clues in the remains. The result is the largest set of ancient DNA from Africa to date. It opens a clear window onto a population that stayed apart for an astonishing length of time.

“This group seems to have been genetically separate for at least 200,000 years,” said Mattias Jakobsson, a geneticist at Uppsala University who led the project. “It’s only relatively late, around 1,400 years ago, that we see clear traces of gene flow.”

The findings upend the idea that early modern humans appeared in East Africa and only later drifted south. The evidence now says modern humans lived in southern Africa far earlier than many thought.

Most of the ancient people carried a maternal DNA line called L0d, common today among Khoe-San communities. Several men also had a rare Y chromosome linked to the same groups. Only two men from the past 500 years carried a different line tied to migrants from East Africa.

The seven clearest genomes tell another story. These people likely had dark skin and brown eyes. They could not digest milk as adults. They lacked genetic defenses against malaria and sleeping sickness that were already common in parts of West Africa centuries ago.

When scientists compared the ancient DNA to modern groups around the world, a striking pattern appeared. Human diversity formed a “V.” Non-Africans sat at one point. West and Central Africans sat at another. The ancient southern Africans stood at the third.

Many of the ancient people did not match any group alive today, including the Khoe-San. They marked one edge of human variation. When researchers modeled ancestry, the early southern group showed a single, unmixed genetic signature. That pattern held until about 1,400 years ago.

Nothing suggests outsiders moved into the far south for most of that long stretch. Yet people from the south did not remain locked in place. By about 8,000 years ago, traces of southern ancestry appeared in ancient people from what is now Malawi and Zambia.

Clear evidence of newcomers arriving in southern Africa arrives much later. Between 1,300 and 700 years ago, some people carried genes from East African herders. In the last 600 years, the picture grows more tangled. Some people still showed only the ancient southern line. Others carried small amounts of East African or European ancestry. A few had large West African contributions.

Modern Khoe-San people still hold much of this ancient legacy, about 79 percent on average in carefully chosen samples. Yet none are genetic copies of their ancestors. The distance between ancient southern Africans and today’s Juǀ’hoansi is about as wide as that between people in Finland and China.

Carina Schlebusch, a geneticist at Uppsala University, said the new work finally shows a clear outline. “We are now beginning, for the first time, to gain insights at a population level,” she said. “This gives us a much clearer basis for understanding how modern humans evolved.”

For generations, this population was neither tiny nor weak. Genetic diversity inside the group matches that of other ancient Africans. The team used a method that estimates past population size from DNA. It suggests this group stayed large for hundreds of thousands of years, then shrank during the last Ice Age.

The pattern points to southern Africa as a refugium, a safe zone where people endured hard climates while others struggled. At times, pulses of people may have traveled north during warmer periods. Those journeys may have helped spread tools, ideas and genes across the continent.

That idea fits archaeology. Stone tools at Matjes River change across layers. Methods evolve. Styles shift. Yet the DNA stays steady. “Despite this, the individuals are genetically virtually identical,” Jakobsson said. “There is no evidence of in-migration or population exchange.” In Europe, tool changes often arrive with new people. Here, culture shifted without population turnover.

The study also tackles a big question. What genetic changes made humans “modern”?

Researchers focused on protein-altering changes unique to Homo sapiens and missing in Neandertals and Denisovans. Past studies argued many of these changes were fixed in humans and might guide brain growth.

Ancient southern DNA complicates that view. Many supposedly fixed changes still vary. One famous example sits in a gene called TKTL1, once linked to extra neuron growth. The older form of the gene is common in both ancient and modern Khoe-San people. That makes it unlikely to be a simple key to modern thinking.

Overall, ancient southern people carried hundreds of protein-changing variants that were fixed in their group. Many involve the immune system. Others relate to kidney function and water balance. Seven of the universal human changes in this set point to kidney traits. Jakobsson suggests a reason. “One hypothesis is that these gene variants are linked to sweating,” he said, which depends on tight control of body fluids and may underlie human endurance.

Another surprise is how many unique changes this group carried. More than half of their human-only variants appear in no global sample. By contrast, ancient Eurasians show far fewer private changes. Modern San groups share some of that deep pool, but not all.

The pattern hints at a “mix and match” model of evolution. There may be no single genetic recipe for being human. Different groups carried different blends of changes and still became fully modern.

Marlize Lombard, an archaeologist at the University of Johannesburg, sees a local origin for deep behavior. “The complex behaviors and thinking seen in the southern African record from about 100,000 years ago likely arose locally,” she said, then spread north with people and ideas.

The ancient genomes say your species did not take a single path. It branched, waited, adapted and moved again. In southern Africa, part of your lineage kept its own rhythm for ages. Only recently did it rejoin the wider human story.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ancient DNA reveals southern Africa’s hidden role in the rise of modern humans appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.