High on a bluff above the Irtysh River in northeastern Kazakhstan, a ghost city lies just beneath the grass. From the surface you would only see low, rectangular earthen mounds. Yet under that quiet landscape, archaeologists have uncovered the remains of a vast Bronze Age settlement that reshapes how you think about life on the steppe.

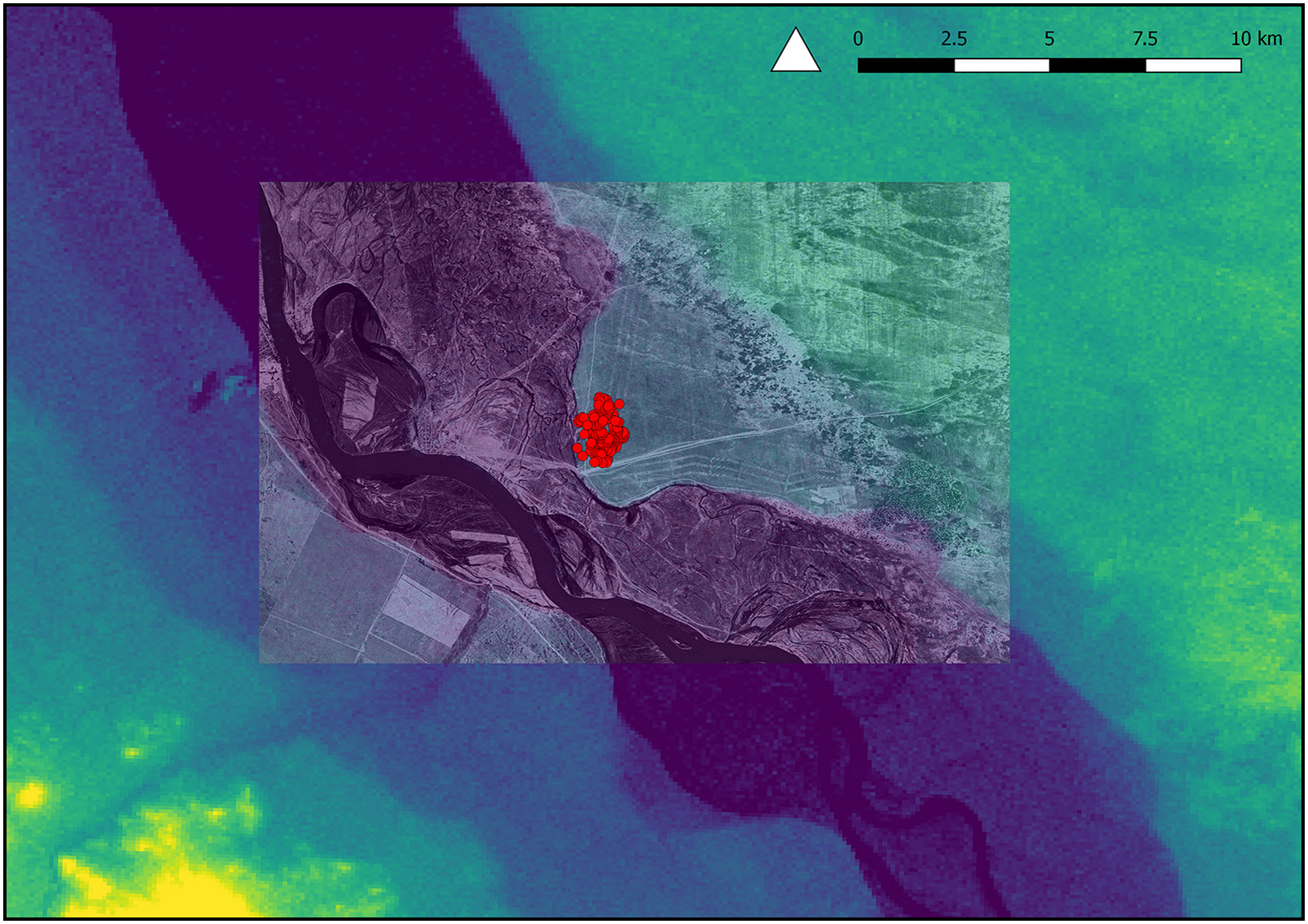

The ancient site, called Semiyarka, dates to around 1600 B.C. and spreads across about 140 hectares. An international team co-led by researchers from UCL, Durham University and Toraighyrov University has now produced the first detailed survey of the city. Their work shows that this was not a loose camp of roaming herders. It was a carefully laid out urban center that likely anchored a major metal industry more than 3,500 years ago.

Lead author Dr. Miljana Radivojević of UCL Archaeology did not hold back her reaction. “This is one of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries in this region for decades,” she said. “Semiyarka changes the way we think about steppe societies. It shows that mobile communities could build and sustain permanent, organized settlements centered on a likely large-scale industry — a true ’urban hub’ of the steppe.”

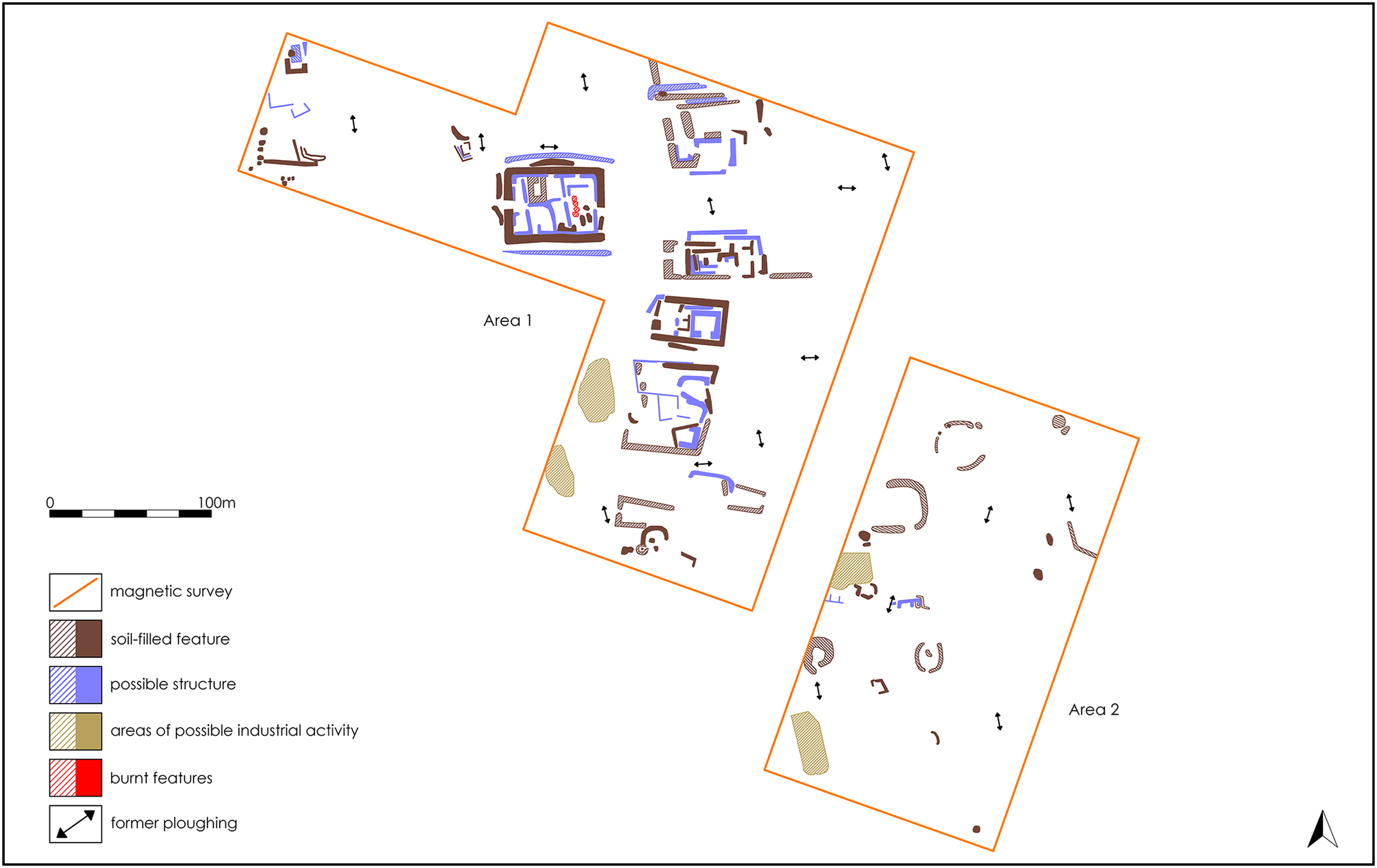

Archaeologists describe the settlement as a planned town rather than a cluster of huts. Two long rows of rectangular house platforms stretch across the promontory. Each platform once supported an enclosed dwelling with several rooms. The raised earthen outlines are only about a meter high today, but they trace a regular street pattern that speaks to careful design.

Near the middle of the site, the team identified a much larger structure, about twice the size of the surrounding homes. Its purpose is still a mystery. It may have served as a communal hall, a ritual space or the residence of an influential family. Whatever happened there, the building stands out as a focal point and hints at shared gatherings or local authority.

Until now, scholars thought that people in this part of the steppe lived mostly in small villages or mobile camps. The scale and permanence of Semiyarka came as a surprise.

Co-author Professor Dan Lawrence of Durham University underlined that shift. “The scale and structure of Semiyarka are unlike anything else we’ve seen in the steppe zone,” he said. “The rectilinear compounds and the potentially monumental building show that Bronze Age communities here were developing sophisticated, planned settlements similar to those of their contemporaries in more traditionally ‘urban’ parts of the ancient world.”

For you, that means rethinking the old picture of endless tents and herds. At least some steppe communities were investing in long-lasting homes and shared infrastructure.

The city was not only a place to live. Evidence points to Semiyarka as a major center for tin bronze production. That metal, an alloy of copper and tin, defined the Bronze Age and fueled weapons, tools and ornaments across Eurasia.

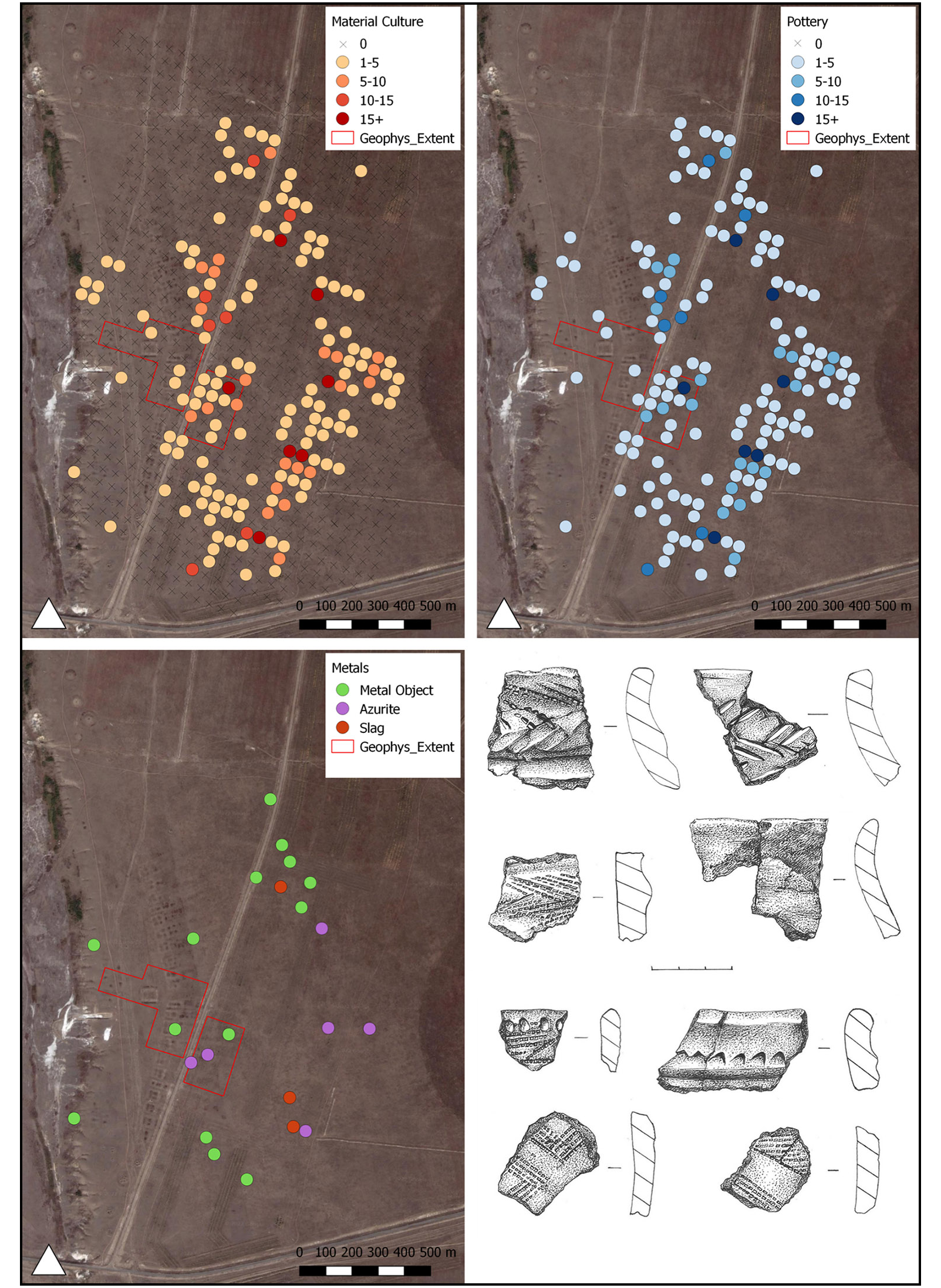

On the southeast edge of the settlement, researchers identified what they call an industrial zone. Excavations and geophysical surveys revealed crucibles used for smelting, chunks of slag from furnaces and finished tin bronze artifacts. Those finds show that craftspeople were not working in scattered backyard forges. They were running complex, concentrated production systems.

“That is rare for the Eurasian steppe. Hundreds of thousands of tin bronze objects from the region sit in museum collections, but only one other site, the Late Bronze Age mining complex of Askaraly in eastern Kazakhstan, has been clearly tied to making the alloy. Semiyarka adds a new piece: an entire district of a city devoted to turning ore into metal,” Professor Lawrence noted in comments to The Brighter Side of News.

Because the settlement lies close to copper and tin deposits in the Altai Mountains, it likely tapped those resources. Its strategic position above the Irtysh River and overlooking seven ravines, which give the site its name “Semiyarka” or “Seven Ravines,” suggests that it also served as a crossroads for trade and exchange.

Finds from homes and rubbish layers help you picture daily life there. Pottery fragments and metal pieces match the styles of the Alekseevka-Sargary culture, whose people were among the first in the region to build permanent houses. Other artefacts resemble items linked to the more mobile Cherkaskul groups, who moved widely across the steppe.

That mix hints at contact and trade between different communities, rather than isolation. Semiyarka may have drawn in workers, traders and visitors from across the region who came to exchange goods or raw materials. For a traveler at the time, the city rising above the river would have been a clear landmark of local power.

Co-author Dr. Viktor Merz of Toraighyrov University first recorded the site in the early 2000s and has spent years surveying it. “I have been surveying Semiyarka for many years with the support of Kazakh national research funding, but this collaboration has truly elevated our understanding of the site,” he said. “Working with colleagues from UCL and Durham has brought new methods and perspectives, and I look forward to what the next phase of excavation will reveal now that we can draw on their specialist expertise in archaeometallurgy and landscape archaeology.”

Nearby, the team has spotted several burial grounds and smaller, temporary settlements from the same era. Those sites may show how people moved between mobile herding, seasonal camps and this more permanent urban center.

When you learn about early cities, you often hear about Mesopotamia, Egypt or the Indus Valley. The grassy plains of Kazakhstan rarely appear in that list. Semiyarka challenges that silence.

The site shows that urban style life did not belong only to river valleys and walled capitals. Steppe communities could also build organized, long-lived settlements tied to industry and trade. They were not just passing through the landscape. They were reshaping it.

In coming years, the research team hopes to dig deeper into how production was organized, who controlled access to metal and how far Semiyarka’s influence spread. They also want to gauge the environmental cost of large scale bronze working, from fuel use to impacts on local vegetation.

As those answers emerge, the story of the Bronze Age steppe will likely become more complex and more human. Instead of a flat zone of wandering herders, you see a mosaic of camps, villages and cities, each with its own role and rhythm.

This work does more than fill in a blank on an ancient map. It pushes archaeologists to look for other large, planned settlements in places long seen as purely nomadic. That shift could spark new surveys across the steppe and other grassland regions and may reveal more hidden centers of industry and trade.

Understanding how Semiyarka organized metal production and exchange can also help trace the routes by which bronze goods and ideas spread across Eurasia. For you as a reader, that changes how you see early globalization. The steppe was not just a corridor between “real” civilizations. It held its own urban hubs that took part in shaping the Bronze Age world.

The study also underscores the value of international collaboration. By combining local experience with advanced methods like geophysical mapping and metallurgical analysis, researchers can rescue fragile sites from erosion, farming and modern development. That protects cultural heritage and gives nearby communities a stronger sense of their deep past.

Finally, insights into how early societies managed resources, built industry and dealt with environmental limits can inform modern debates. When you look at Semiyarka, you see a community that thrived by harnessing local ores and trade routes. You also see the risks of tying a whole landscape to a single, intense industry. Those lessons still matter in a world wrestling with how to balance growth, inequality and environmental change.

Research findings are available online in the journal Antiquity.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Archeologists find the lost Bronze Age city of Seven Ravines appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.