New insights are emerging into one of astronomy’s most perplexing signals. An international research team led in part by scientists from the University of Hong Kong has found strong evidence that at least some fast radio bursts come from stars locked in binary systems rather than single stars.

The work centers on a repeating fast radio burst called FRB 20220529, also known as FRB 220529A. Using China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, known as FAST, and Australia’s Parkes radio telescope, researchers tracked the source for nearly two years. Their results were published in the journal Science.

Professor Bing Zhang, an astrophysicist at the University of Hong Kong and founding director of the Hong Kong Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, served as a corresponding author on the study. He and his colleagues report what they describe as the first decisive evidence that a repeating fast radio burst source can orbit a companion star.

“This finding provides a definitive clue to the origin of at least some repeating FRBs,” Zhang said. “The evidence strongly supports a binary system containing a magnetar, a neutron star with an extremely strong magnetic field, and a star like our Sun.”

Fast radio bursts, or FRBs, are brief flashes of radio energy that last only milliseconds but shine brighter than entire galaxies at radio wavelengths. Most appear once and vanish. A small number repeat, which allows scientists to study how their signals change over time.

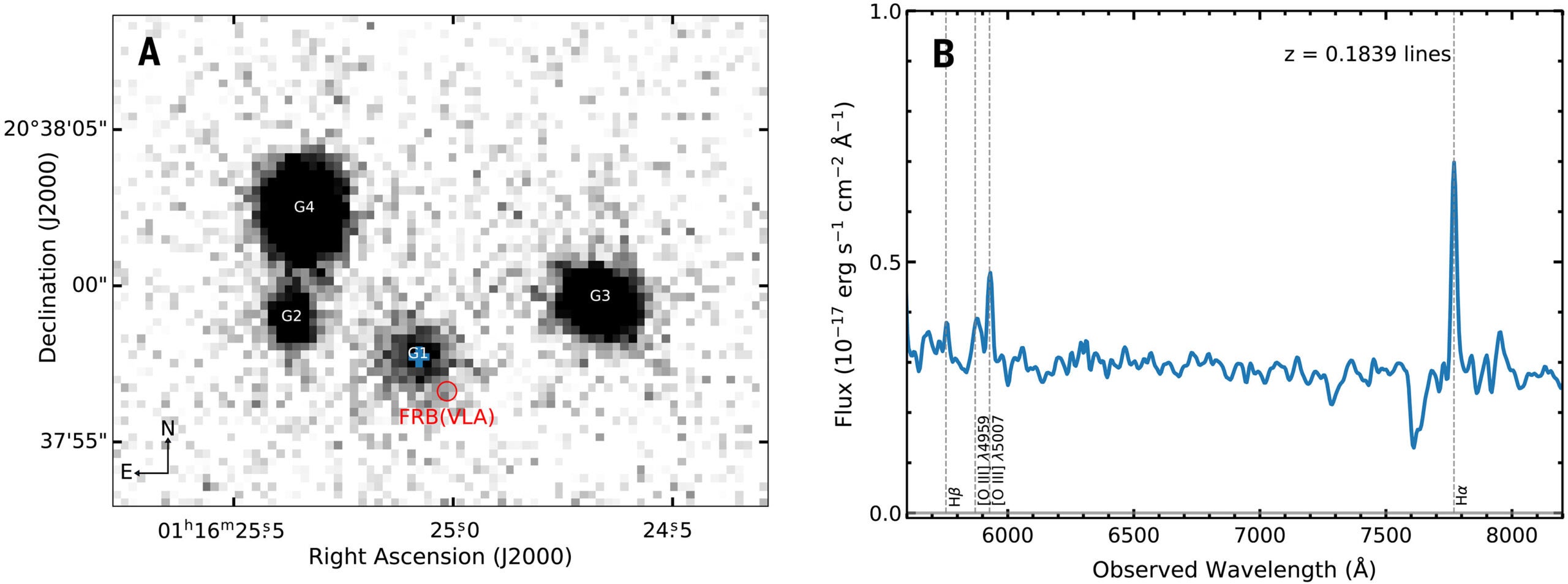

FRB 20220529 was first detected in May 2022 by the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment, or CHIME. Its signal showed that it came from far beyond the Milky Way, roughly 2.5 billion light-years away. Follow-up observations soon confirmed that the source repeats.

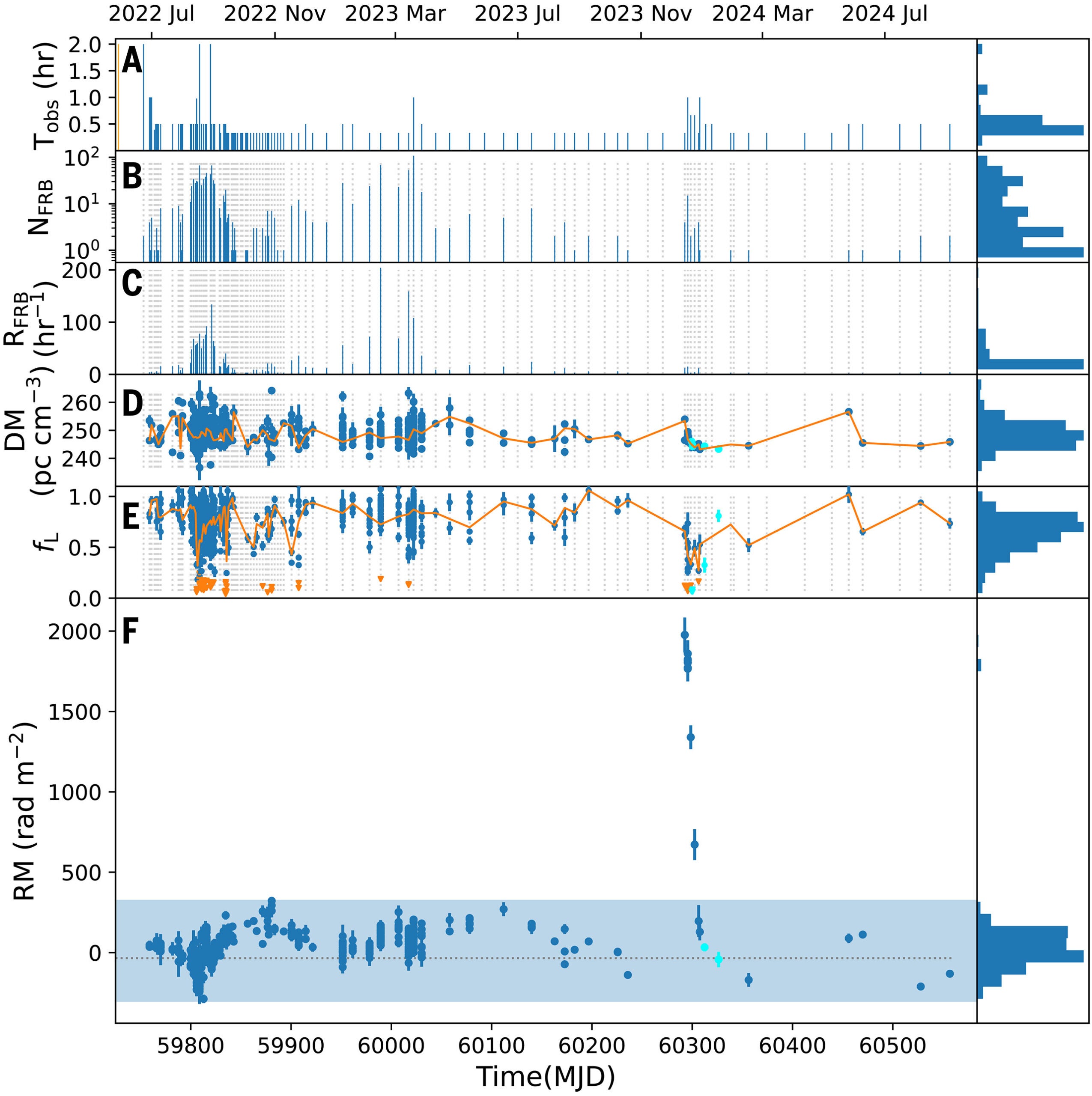

FAST began regular monitoring of the burst in 2022 as part of a long-term program co-led by Zhang. Over 2.2 years, FAST observed the source during 112 sessions, while Parkes contributed 59 sessions. FAST alone spent nearly 48 hours pointed directly at the burst location.

During that time, FAST detected 1,156 individual bursts, while Parkes recorded 56. The source proved unusually active. At its peak, it produced more than 200 bursts per hour. Even during quieter periods, it averaged about 7.5 bursts per hour, far longer than most known repeaters.

“FRB 220529A was monitored for months and initially appeared unremarkable,” Zhang explained to The Brighter Side of News. “Then, after a long-term observation for 17 months, something truly exciting happened.”

The key clue came from polarization, which describes the orientation of radio waves. Fast radio bursts are often highly polarized, meaning their waves line up in a consistent direction. As those waves pass through magnetized plasma, their polarization angle rotates in a process called Faraday rotation. Scientists measure this effect using a quantity called rotation measure, or RM.

For more than a year, the RM of FRB 20220529 fluctuated modestly, sometimes changing sign. That behavior pointed to a turbulent environment near the source. Then, late in 2023, everything changed.

“Near the end of 2023, we detected an abrupt RM increase by more than a factor of a hundred,” said Dr. Ye Li of Purple Mountain Observatory and the University of Science and Technology of China, the study’s first author.

The RM jumped to nearly 2,000 radians per square meter and then fell back to normal levels within about two weeks. The team calls this short-lived event an “RM flare.”

“The RM then rapidly declined over two weeks, returning to its previous level,” Li said. “We call this an RM flare.”

During the same period, the bursts briefly lost much of their strong linear polarization, dropping from about 80 percent to roughly 27 percent before recovering. The timing tied both changes to the same physical event.

The researchers considered several possible causes for the RM flare. A sudden outflow from the magnetar itself seemed unlikely, since similar changes have not been seen in known magnetars in the Milky Way. Turbulence in a supernova remnant also failed to match the sharp rise and fall of the signal.

The most convincing explanation involves a nearby companion star. In this scenario, the companion released a dense cloud of magnetized plasma, similar to a coronal mass ejection from the Sun. As that cloud crossed the narrow line of sight between Earth and the magnetar, it temporarily altered the radio signal.

“One natural explanation is that a nearby companion star ejected this plasma,” Zhang said.

Professor Yuanpei Yang of Yunnan University, a co-first author, said models based on stellar eruptions fit the data well. “The required plasma clump is consistent with CMEs launched by the Sun and other stars in the Milky Way,” he said.

Although the companion star cannot be seen directly at such distances, its presence was revealed through the changing radio signal. The work relied on persistent monitoring by FAST and Parkes.

“This discovery was made possible by the persevering observations using the world’s best telescopes and the tireless work of our dedicated research team,” said Professor Xuefeng Wu of Purple Mountain Observatory, the lead corresponding author.

Earlier studies had already linked some fast radio bursts to magnetars, especially young ones in star-forming galaxies. This new result strengthens a growing view that interactions within binary systems may shape how repeating bursts behave.

The team also supports a broader model proposed by Zhang and collaborators in which all fast radio bursts come from magnetars. In that picture, binary companions can create favorable conditions that allow bursts to repeat and be detected more often.

Only one RM flare was seen during more than two years of observation, suggesting such events are rare. Still, researchers expect more examples to emerge as monitoring continues.

This discovery changes how you understand fast radio bursts and their origins. By showing that at least some repeating bursts come from binary systems, the study gives researchers a clearer framework for interpreting these signals. It helps explain why some sources repeat for years while others appear only once.

In the future, astronomers can search for similar polarization changes in other repeaters to identify hidden companion stars. That approach may reveal how common binary systems are among fast radio burst sources. Beyond that, the work offers a new way to study stellar eruptions and magnetic environments in distant galaxies, using fast radio bursts as natural probes of space billions of light-years away.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers discover the binary origin of fast radio bursts appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.