In the nearby Andromeda Galaxy, a massive star bright enough to stand out for years has gone dark. Not in a blaze of glory. Not in a supernova that would briefly outshine its entire galaxy. It just faded.

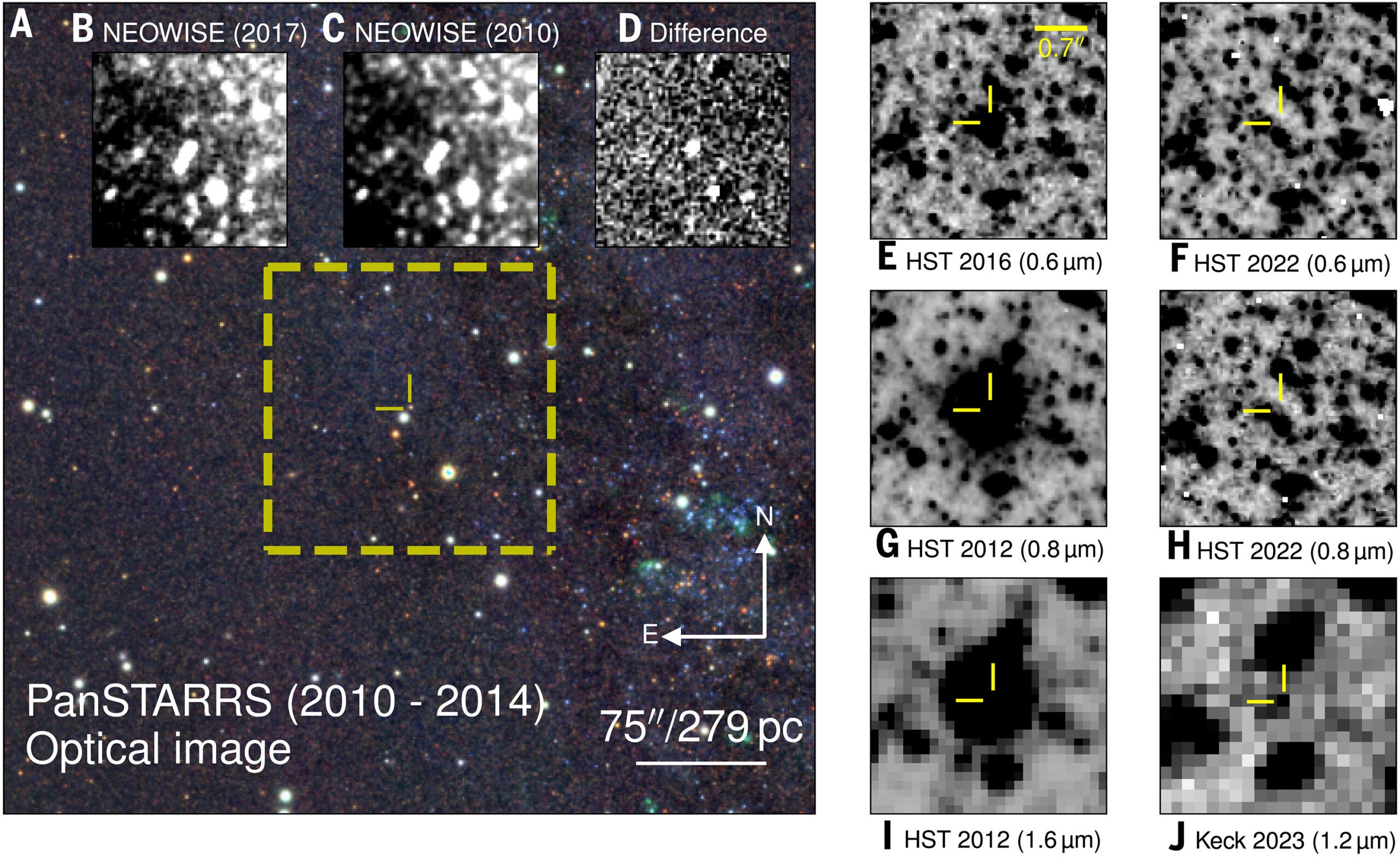

The object, known as M31-2014-DS1, sits about 2.5 million light-years away in M31. Kishalay De of the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute led the effort to track what happened. The team pulled together data from NASA’s NEOWISE mission and a long list of ground and space telescopes, combing through observations from 2005 to 2023. Their findings were published February 12 in Science.

At first, nothing seemed catastrophic. In 2014, the star brightened in mid-infrared light by about 50 percent over two years. Then the trend reversed. By 2016 it had dimmed below its original level. The decline did not stop.

By 2023, it had effectively vanished in visible light.

Optical surveys showed the star faded by a factor of about 10,000 between 2016 and 2019. Follow-up imaging in 2023 with the MMT Observatory could not detect it at all in optical wavelengths. Hubble Space Telescope data from 2022 found no sign of the star in one optical filter and only a faint source in the near-infrared. Observations in 2023 with the Infrared Telescope Facility and the Keck telescopes confirmed a dim red remnant in near-infrared bands.

Today, the source is visible only in mid-infrared light, glowing at roughly one-tenth of its former brightness there.

“This star used to be one of the most luminous stars in the Andromeda Galaxy, and now it was nowhere to be seen,” De says. “Imagine if the star Betelgeuse suddenly disappeared. Everybody would lose their minds! The same kind of thing [was] happening with this star in the Andromeda Galaxy.”

The data point to a stark conclusion. The star’s core collapsed and formed a black hole. No successful supernova followed.

Massive stars usually end with an explosion. As they burn through fuel, gravity presses inward while fusion pushes outward. When fuel runs low, the core collapses. Neutrinos can drive a shock that blasts off the outer layers, producing a core-collapse supernova.

That did not happen here.

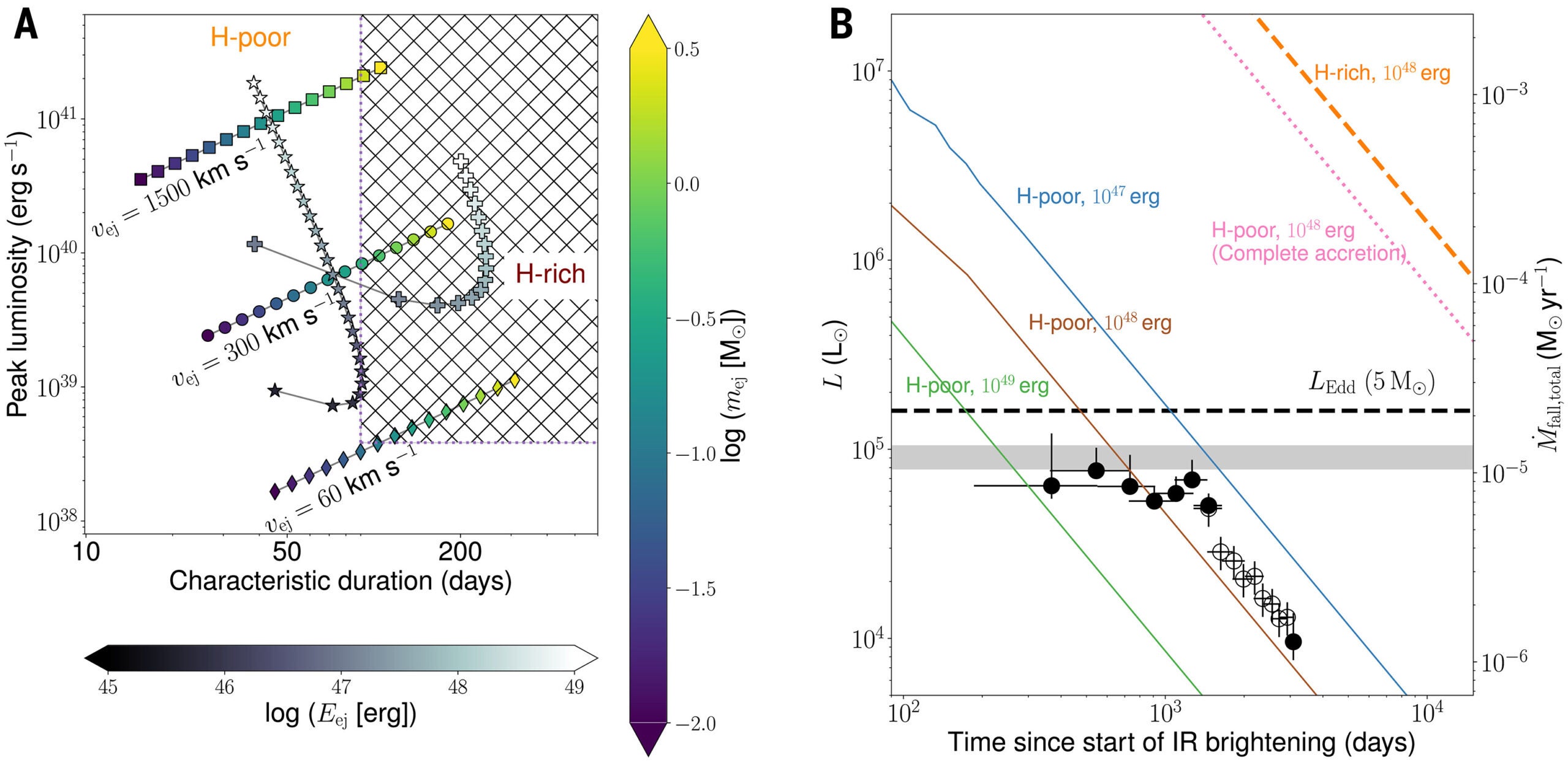

The team found no evidence of a supernova bright enough to have been seen. Instead, the star’s total energy output dropped and kept dropping. The bolometric luminosity stayed roughly constant for about 1,000 days after the mid-infrared brightening began. Then it declined over the next 1,000 days.

If dust alone were blocking the light, the infrared emission would have increased to compensate. It did not. The total radiated energy fell. Nuclear fusion had ceased.

The researchers interpret M31-2014-DS1 as a failed supernova. Most of the roughly 5 solar masses of the final star collapsed, exceeding the maximum mass of a neutron star and forming a black hole.

“We’ve known for almost 50 years now that black holes exist,” De says, “yet we are barely scratching the surface of understanding which stars turn into black holes and how they do it.”

Archival data show the star was a supergiant with a luminosity of about 10^5 times that of the Sun and an effective temperature near 4,500 kelvin. Although once classified as a red supergiant candidate, modeling suggests it was hotter, more like a yellow supergiant. It was surrounded by a dusty shell about 110 astronomical units from the star, with dust near 870 kelvin.

After the collapse, only a small fraction of the outer envelope was ejected. The team set limits on how much mass could have been thrown off, finding that most of the star fell back inward. Weak shock energies between 10^47 and 10^48 ergs best match the fading pattern. Those values are far below the roughly 10^51 ergs typical of supernova explosions.

Material that did escape cooled and formed dust. Models suggest about 0.1 solar masses of gas were ejected, with a dust-to-gas ratio near 0.01. The hot dust mass in the shell is around 10^−4 solar masses, consistent with what the spectral energy distribution shows.

Convection inside the star likely shaped this outcome. Turbulent motion in the outer layers carried angular momentum. Instead of plunging straight into the newborn black hole, some material orbited first, slowing the infall. Only a small fraction accreted directly.

Andrea Antoni, a Flatiron Research Fellow and co-author, helped develop the theoretical framework for this process. “The accretion rate — the rate of material falling in — is much slower than if the star imploded directly in,” she says. “This convective material has angular momentum, so it circularizes around the black hole. Instead of taking months or a year to fall in, it’s taking decades. And because of all this, it becomes a brighter source than it would be otherwise, and we observe a long delay in the dimming of the original star.”

The lingering mid-infrared glow may persist for decades.

The team revisited another disappearing star, NGC 6946-BH1, first identified years ago. That object showed an optical outburst and then faded over about 3,000 days. By constructing models with enhanced late-stage mass loss, the researchers found a similar story: a hydrogen-depleted massive star collapsing into a black hole.

M31-2014-DS1 had more archival coverage, allowing tighter limits on any missed outburst. In both cases, the evidence favors core collapse without a successful supernova.

Using prior estimates for the fraction of failed supernovae, the team calculated only a 1 to 20 percent chance of finding at least one such event in their survey. Yet they did.

“It’s only with these individual jewels of discovery that we start putting together a picture like this,” De says.

This work sharpens the view of how black holes form from massive stars. Not every giant ends in a bright explosion. Some simply fade, leaving behind a black hole and a faint dust glow.

Understanding which stars explode and which collapse quietly affects how astronomers estimate black hole populations across galaxies. It also shapes models of chemical enrichment, since failed supernovae return less material to space.

Long-term infrared monitoring, especially with sensitive telescopes, could reveal more of these silent endings. Each case adds another piece to a puzzle that has remained incomplete for decades.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

The original story “Astronomers observe a massive star vanish and turn into a black hole” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers observe a massive star vanish and turn into a black hole appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.