Researchers at the University of British Columbia and Dalhousie University have found a young galaxy cluster that appears far hotter than theory allows. The international team, working with the National Research Council of Canada and using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, reported the discovery in the journal Nature.

The study was led by Dazhi Zhou, a doctoral student in the UBC department of physics and astronomy. The work also involved Dr. Scott Chapman, a professor at Dalhousie University and an affiliate professor at UBC, who carried out much of the research while at the National Research Council of Canada.

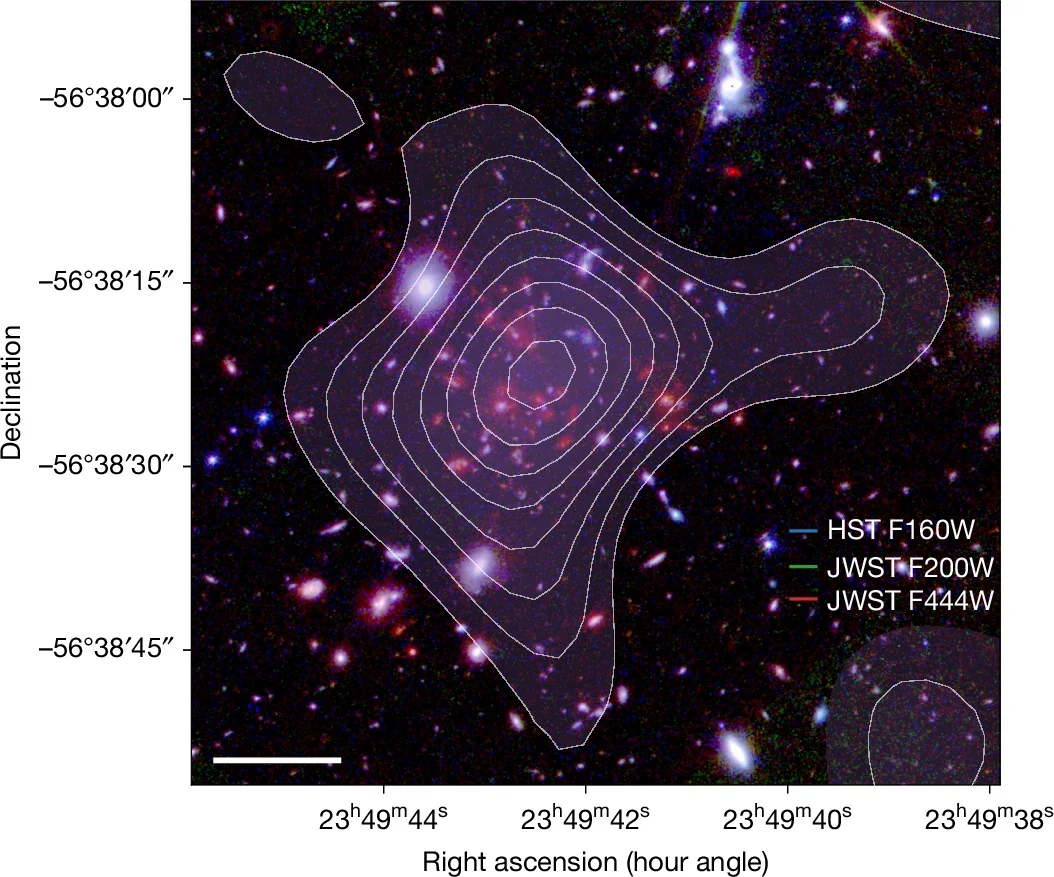

The scientists focused on a distant system called SPT2349–56. It existed just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, when most galaxy clusters were still forming. Yet this object already holds an atmosphere of hot gas more extreme than many clusters in the modern universe.

“We did not expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” Zhou said. “In fact, at first I was skeptical about the signal as it was too strong to be real. But after months of verification, we have confirmed this gas is at least five times hotter than predicted, and even hotter and more energetic than what we find in many present-day clusters.”

SPT2349–56 was first spotted in a large survey by the South Pole Telescope. It stood out as the brightest protocluster candidate across 2,500 square degrees of sky. The system lies at a redshift of 4.3, meaning its light has traveled for about 12 billion years.

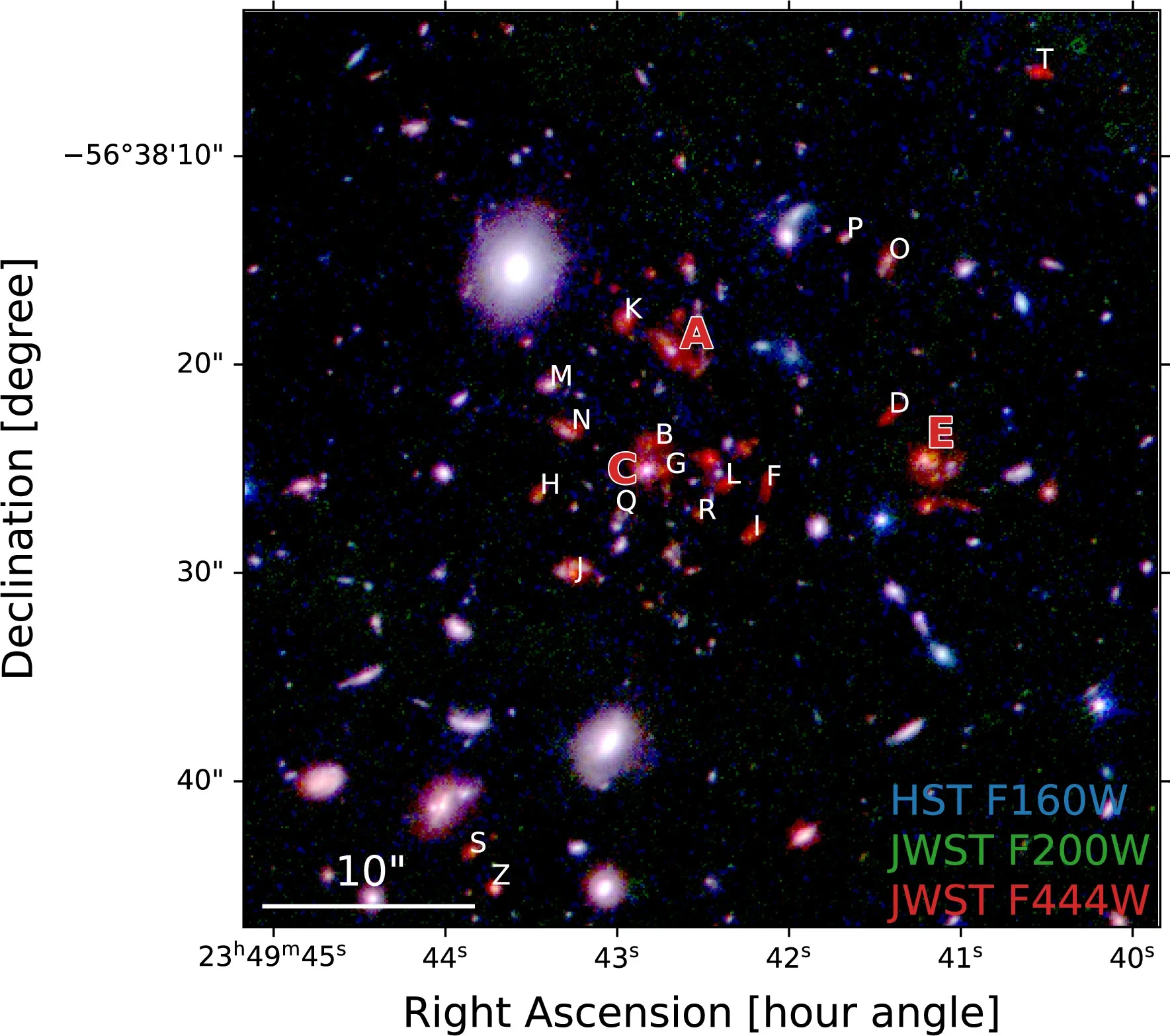

The core of the cluster stretches about 500,000 light-years across. That is similar to the halo that surrounds the Milky Way. Inside that tight space sit more than 30 active galaxies. Together they form stars at a rate about 5,000 times higher than in the Milky Way.

Earlier observations also found at least three radio-loud supermassive black holes in the core. Astronomers call these objects active galactic nuclei. Their intense energy output can affect the gas around them.

“This tells us that something in the early universe, likely three recently discovered supermassive black holes in the cluster, were already pumping huge amounts of energy into the surroundings and shaping the young cluster, much earlier and more strongly than we thought,” Chapman said.

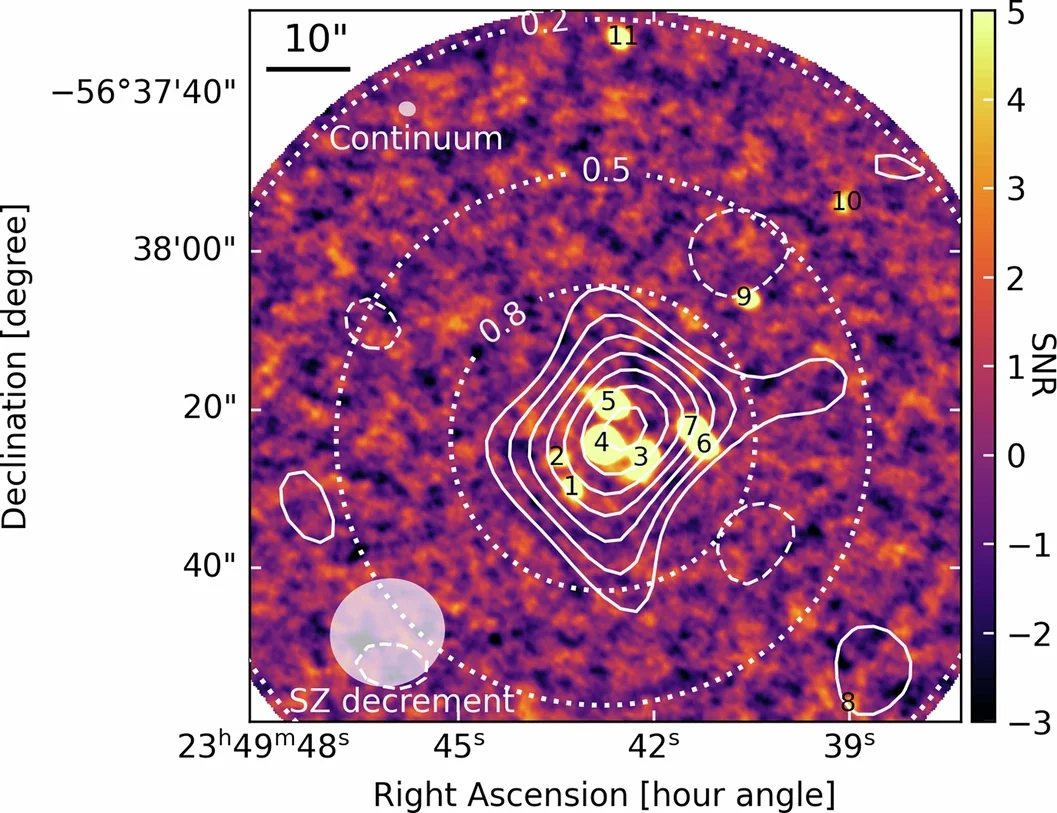

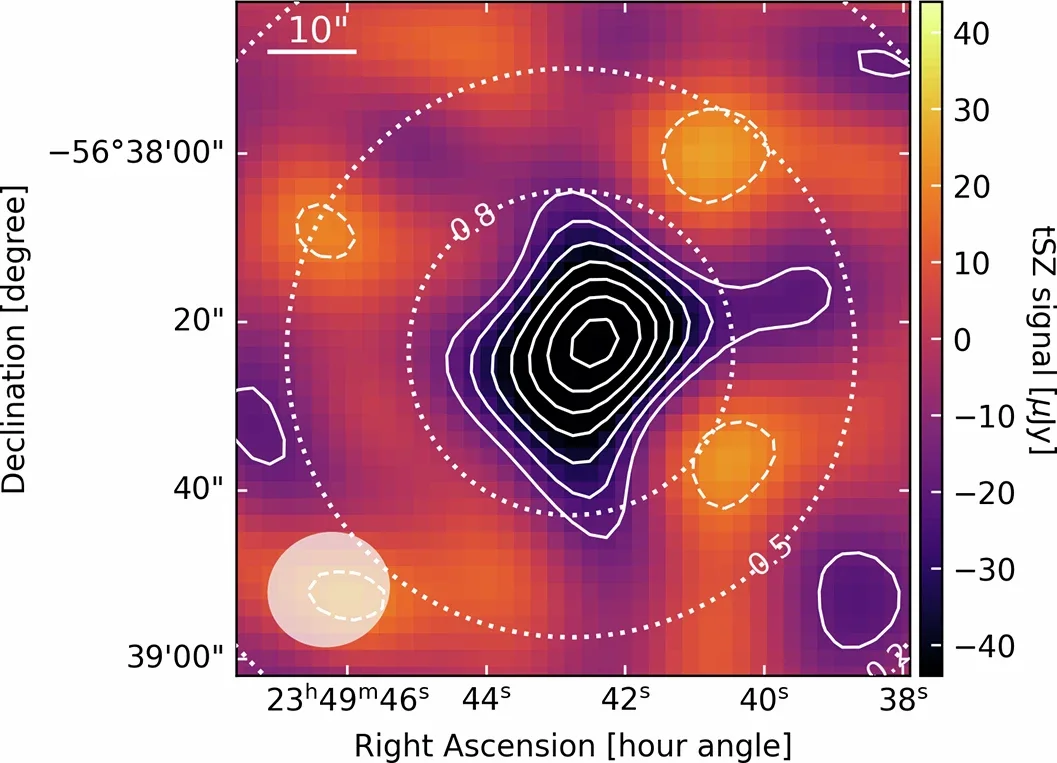

“To study the cluster, our team relied on a subtle signal known as the thermal Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect. This effect appears when photons from the cosmic microwave background pass through hot electrons. The photons gain energy, leaving a small dip in the background at long wavelengths,” Zhou explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“The strength of that dip depends on the pressure and temperature of the gas. It does not depend on how far away the cluster is. That makes it a powerful tool for probing young systems in the distant universe,” he continued.

Using ALMA, which includes instruments designed and tested by the National Research Council of Canada, the team measured a strong Sunyaev–Zeldovich signal in SPT2349–56. Even after subtracting dust from the many star-forming galaxies, a deep negative signal remained in the center of the cluster.

That signal revealed a huge reservoir of hot gas. From it, the researchers estimated the total thermal energy of the gas to be about 10^61 ergs. That is far higher than what standard models predict for a cluster of this size and age.

In current models, clusters grow as gravity pulls matter inward. Gas falls into the deepening gravitational well and heats up as it is compressed. In a young protocluster, that process should still be mild.

For a system like SPT2349–56, theory predicts gas temperatures near one million degrees. The new data point to values several times higher. The amount of thermal energy implied by the Sunyaev–Zeldovich signal exceeds expectations by at least a factor of five.

Even if the cluster were much heavier than thought, gravity alone could not explain the measurement. The result suggests that an extra source of heat is already at work.

The leading candidate is energy from the active black holes in the cluster core. Jets and winds from these objects can carry enormous power. In a dense early environment, that energy may stay trapped, raising the temperature of the surrounding gas.

“We want to figure out how the intense star formation, the active black holes and this overheated atmosphere interact, and what it tells us about how present galaxy clusters were built,” Zhou said. “How can all of this be happening at once in such a young, compact system?”

Simulations of galaxy cluster growth usually predict that early systems should have less hot gas than their mature descendants. The new observation shows the opposite in this case.

The Sunyaev–Zeldovich signal from SPT2349–56 sits far above the normal link between cluster mass and hot gas pressure. That means its intracluster medium does not behave like that of settled clusters nearby.

The finding hints that some young clusters pass through a brief, violent stage. During that time, black hole activity and rapid star formation may dump huge amounts of energy into their surroundings. The result could be a short-lived but extreme hot phase.

Such a phase has not appeared in current computer models. That gap suggests that scientists may need to adjust how they describe black hole feedback in the early universe.

This discovery changes how scientists think about the birth of galaxy clusters. If black holes can heat young clusters so strongly, it means they play a larger role in shaping the largest structures in the universe. That insight will guide future models of cosmic evolution and improve how researchers interpret distant clusters seen by new telescopes.

Understanding these early stages also helps scientists trace how the biggest galaxies formed. Since many giant galaxies live in clusters, knowing how their environments developed can explain why those galaxies look the way they do today.

In the long term, better models of cluster growth will sharpen measurements of dark matter and the expansion of the universe.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers spot a hot galaxy cluster that defies existing cosmic theory appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.