A supermassive black hole with a case of cosmic indigestion has been burping out the remains of a shredded star for four years; it is still going strong.

That strange show is now being tracked by University of Oregon astrophysicist Yvette Cendes and her colleagues. Their new study, published in The Astrophysical Journal, says the black hole’s radio blast could keep climbing fast, then peak in 2027.

“This is really unusual,” said Cendes, an astrophysicist at the UO who led the work. “I’d be hard-pressed to think of anything rising like this over such a long period of time.”

The object is officially called AT2018hyz. Cendes likes a fun nickname too, “Jetty McJetface,” a nod to the internet-famous British research vessel Boaty McBoatface.

Scientists know what starts the drama. A star drifts too close to a supermassive black hole. Gravity stretches and tears the star apart in a tidal disruption event, often called a TDE. Some researchers even call the tearing “spaghettification.”

In many TDEs, telescopes spot bright light early, then watch it fade. Astronomers often track that glow in optical, ultraviolet and X-ray light. Radio signals can tell a different story, because they can come from winds or jets that slam into gas nearby.

That is why AT2018hyz grabbed attention. It looked ordinary at first. Back in 2018, Cendes was a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University. A lab mate spotted the event with an optical telescope, and it seemed routine.

“At the time, it was ‘the most boring, garden-variety event,’” Cendes said, so it did not draw much follow-up.

Then the black hole changed its behavior. A few years later, Cendes noticed strong radio waves from the same spot. Her team first reported the surprise in a 2022 paper in The Astrophysical Journal. They kept watching, and the signal kept growing.

Cendes is a radio astronomer. Her team uses large radio facilities that can detect faint signals across the universe. The work draws on data from arrays in New Mexico and South Africa, plus other major instruments.

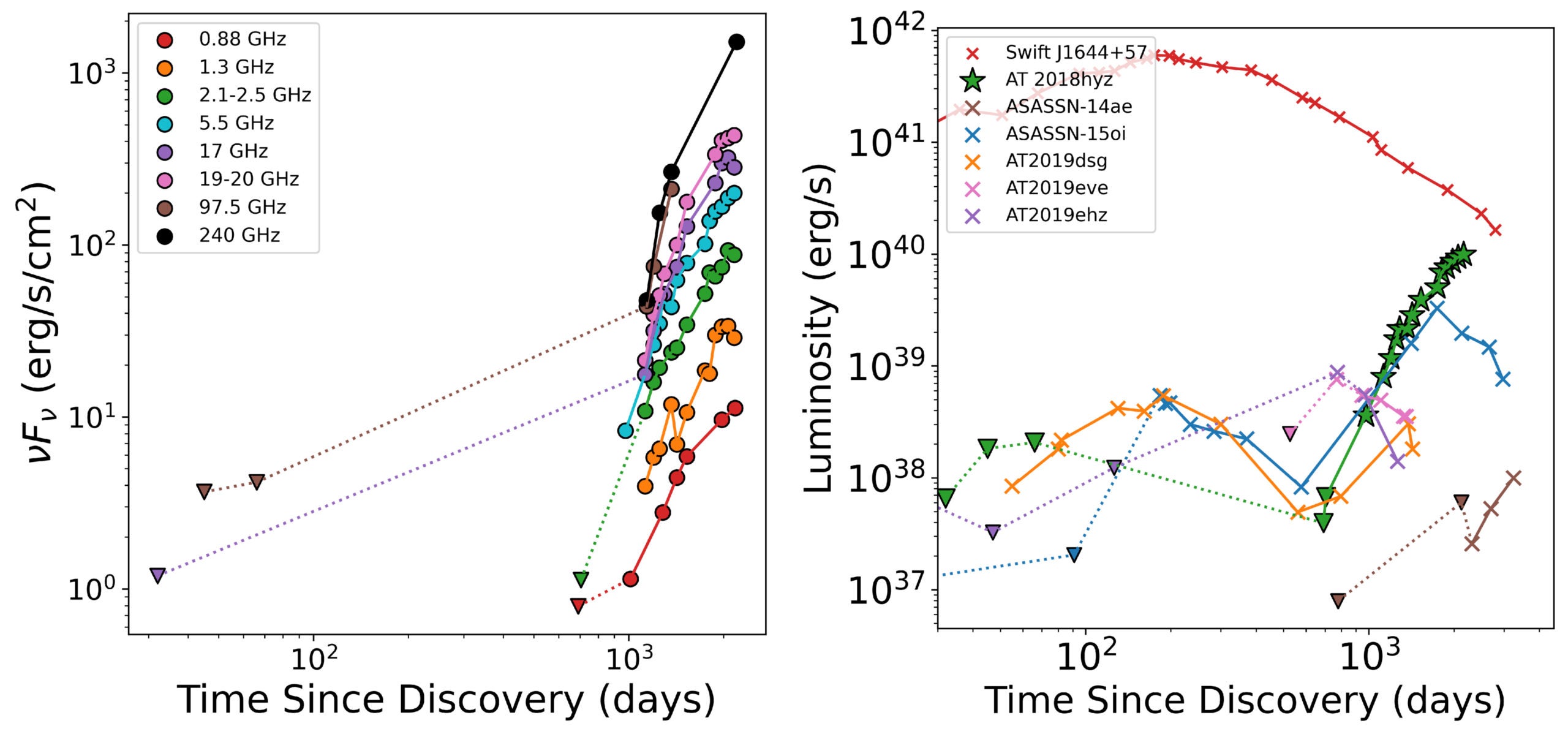

The timeline matters. The optical discovery date used as the reference point is Oct. 14, 2018. Earlier radio data covered about 972 to 1282 days after discovery. New radio coverage stretches from 1366 to 2160 days, and spans roughly 1 to 23 GHz.

The study also adds millimeter data at much higher frequencies. ALMA observed the source at 97.5 GHz and 240 GHz at 1367 and 1441 days. The Submillimeter Array later observed it at 225.5 GHz at 2198 days. Those detections rose over time too.

The team also checked X-rays with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chandra watched in four intervals from Feb. 21 to Feb. 24, 2024. An X-ray source showed up in all four looks, with no strong swings. The X-ray level matched what the team saw earlier, which suggests low-level feeding near the black hole.

Still, the headline result sits in the radio. The black hole’s radio output did not just turn on late. It kept ramping up.

In one well-sampled radio band near 5 to 7 GHz, the flux rose from about 1.4 millijanskys at 972 days to 33.3 millijanskys at 2160 days. That is an eye-popping jump.

Cendes and her colleagues say the source is now 50 times brighter than it was when first detected in radio in 2019. They also estimate the energy output is so large that it rivals a gamma ray burst. That could place it among the most powerful single events ever detected.

Cendes offers a pop-culture yardstick. Star Wars fans have estimated the energy output of the Death Star. This black hole is emitting at least a trillion times that, and possibly closer to 100 trillion times.

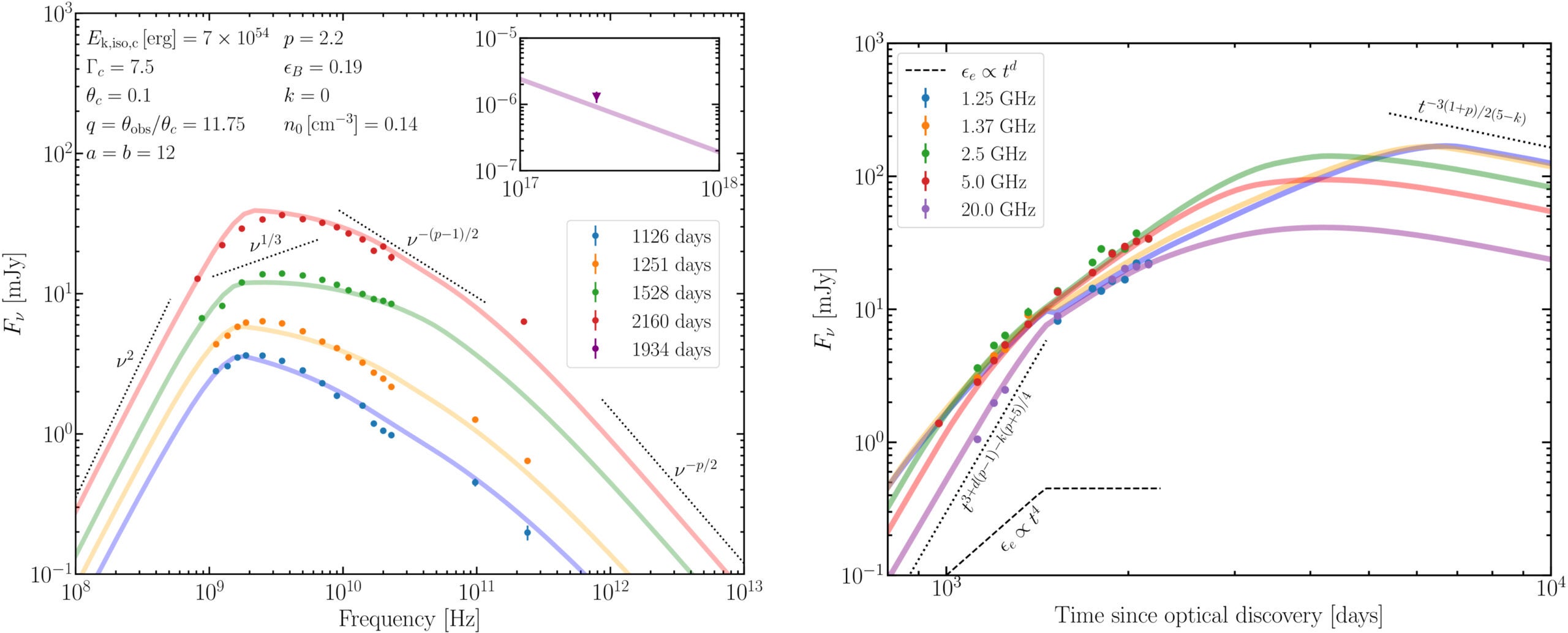

So what is actually happening? The data still allow two main stories.

One idea says the blast is more like a roughly spherical outflow. In that case, the analysis points to a delayed launch, around 620 days after optical discovery. The material would be moving at about one-third the speed of light. The inferred kinetic energy rises over time, reaching about 10^50 erg by the latest observations.

The other idea says a jet launched early, but you are seeing it from the side. If the jet did not point toward Earth, the early signal could look weak. As the jet slows and spreads, more emission becomes visible. In that off-axis picture, the viewing angle could be extreme, around 80 to 90 degrees. The jet energy could approach about 10^52 erg in some fits.

Both stories can explain key clues. The peak frequency stays near a few gigahertz, while the peak brightness rises strongly. Some bands hint at changes, like fading at certain frequencies after about 2050 days. Other bands keep rising.

For now, the team is watching for a turning point. Their calculations suggest the radio signal should keep increasing exponentially before peaking in 2027. A turnover at some frequencies around early 2027 could help sort out which model is right.

Meanwhile, Cendes is searching for other black holes that might do the same thing. Telescope time is tight, and delayed fireworks are easy to miss.

Securing time to gather data on international telescopes is competitive, Cendes said, and “if you have an explosion, why would you expect there to be something years after the explosion happened when you didn’t see something before?”

But now they know to look.

This work could change how astronomers follow star-shredding events. Many TDEs get quick attention, then fade from view. AT2018hyz suggests some of the biggest action can come years later. That could push teams to keep monitoring “quiet” events longer, especially with radio and millimeter telescopes.

The findings also offer a new way to probe how black holes launch jets and outflows. If researchers can tell whether the blast is spherical or a hidden jet, they can learn how matter behaves in extreme gravity. Better models could also help scientists spot more off-axis jets that currently go unnoticed.

Finally, longer tracking can sharpen predictions. If the signal peaks in 2027 as expected, it will give astronomers a rare test of their ideas in real time, using coordinated observations across the globe.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Black hole ‘Jetty McJetface’ keeps brightening years after it shredded a star appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.