At the heart of nearly every large galaxy lies a supermassive black hole. These cosmic giants don’t just sit quietly. Every so often, they enter a period of intense activity called the active galactic nucleus (AGN) phase. During this time, the black hole feeds on nearby gas and dust, releasing huge amounts of high-energy light—including ultraviolet (UV) radiation—into space. What happens when planets, possibly even ones like Earth, get caught in the blast?

In a recent study published in The Astrophysical Journal, researchers from Dartmouth and the University of Exeter explored that question. Using computer simulations, they discovered that AGN radiation doesn’t just spell doom for life. In fact, it might help it thrive—under the right conditions.

When a black hole becomes active, the energy it unleashes can stretch across an entire galaxy. That radiation includes UV light, which is known to harm cells and damage DNA. But the story doesn’t end there.

Supermassive black holes like Sagittarius A*, located at the center of our own Milky Way, have likely gone through several AGN phases in their lifetimes. In fact, evidence suggests our galaxy experienced such a phase a few million years ago. Signs like the Fermi bubbles—giant lobes of high-energy particles extending from the center of the Milky Way—support this idea.

Past research mostly focused on the harmful effects of AGN radiation, including stripping away a planet’s atmosphere or blasting the surface with deadly rays. Some scientists, like those in studies by Amaro-Seoane, Chen, and Lingam, raised alarms about AGN exposure. They suggested that if a planet received as much UV from its central AGN as it does from its star, life would be in serious danger.

But the new study takes a different angle. By applying a powerful computer model used to study radiation from active M dwarf stars—stars known for strong UV flares—the team looked closely at how AGN light interacts with a planet’s atmosphere. They discovered something surprising: once life exists and starts producing oxygen, AGN radiation might actually help that life survive.

Related Stories

The team used the PALEO (Platform for Atmosphere, Land, Earth, and Ocean) model to run detailed simulations. This tool calculates how different gases in a planet’s atmosphere react to incoming radiation over time. The researchers modeled planets with atmospheres like Earth’s, both with and without oxygen.

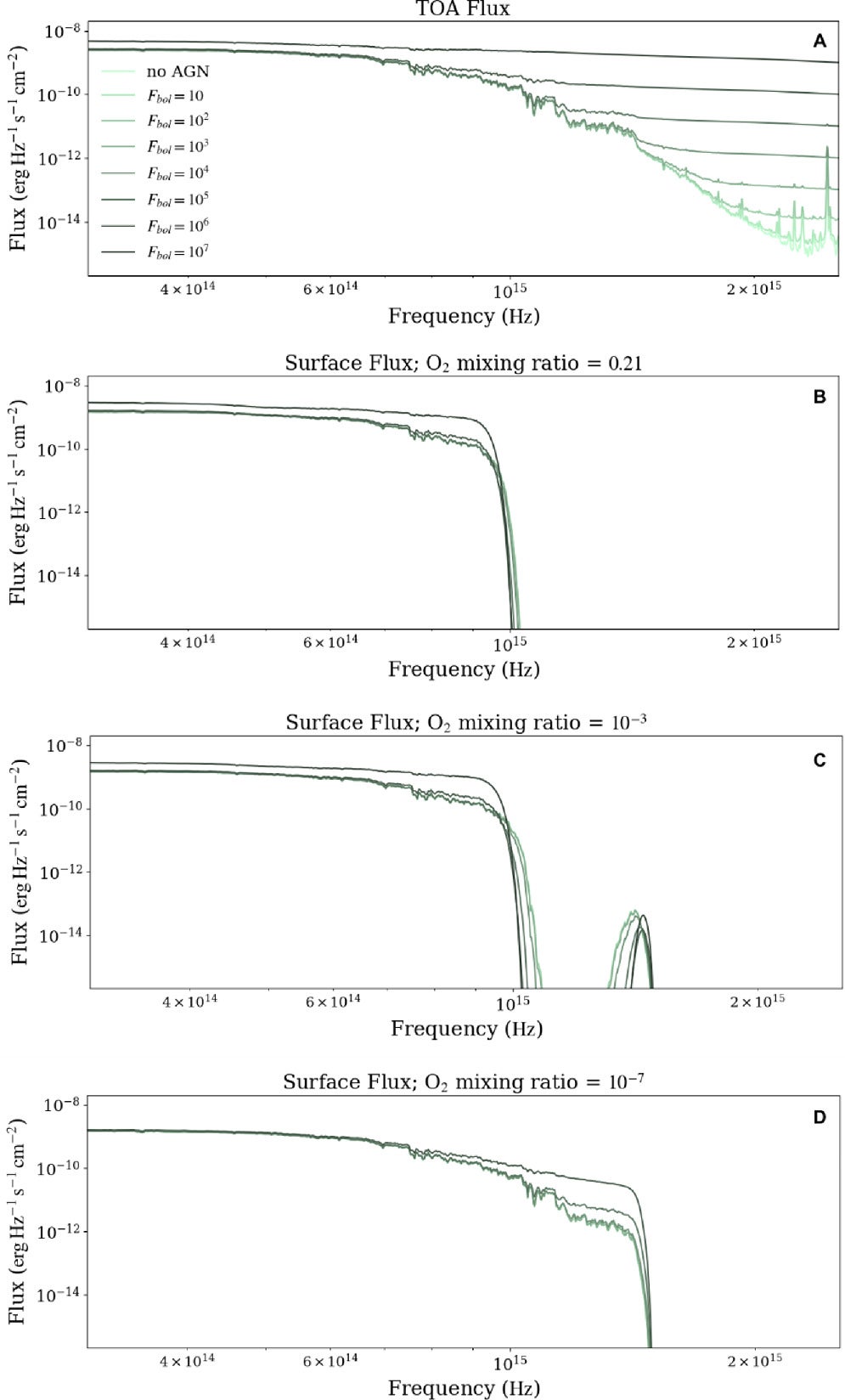

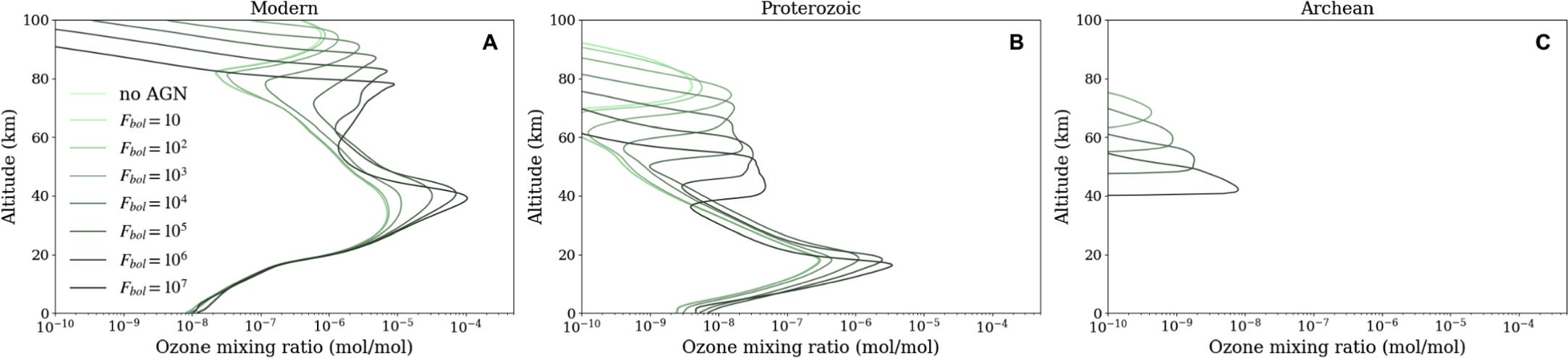

They found that if oxygen was already present, UV radiation from an AGN could spark chemical reactions that produce ozone. Ozone is critical—it forms a protective layer in the upper atmosphere that blocks harmful radiation from reaching the ground.

“Once life exists, and has oxygenated the atmosphere, the radiation becomes less devastating and possibly even a good thing,” says Kendall Sippy, lead author of the study and a recent Dartmouth graduate. “Once that bridge is crossed, the planet becomes more resilient to UV radiation and protected from potential extinction events.”

In the presence of sufficient oxygen—at least 0.1% of the atmosphere—this protective feedback kicks in. The UV light splits oxygen molecules, which then recombine to form ozone. As more ozone builds up, less radiation reaches the surface. The more oxygen present, the faster and stronger the protection becomes.

This process is similar to what happened on Earth around 2 billion years ago. Early microbes began producing oxygen through photosynthesis, and sunlight helped turn that oxygen into ozone. As the ozone layer grew, it protected the surface from radiation, allowing more life to flourish—a feedback loop that continued to strengthen life’s foothold.

Jake Eager-Nash, co-author of the study and a researcher at the University of Victoria, explains, “If life can quickly oxygenate a planet’s atmosphere, ozone can help regulate the atmosphere to favor the conditions life needs to grow. Without a climate-regulating feedback mechanism, life may die out fast.”

But not all planets benefit. For those without oxygen, UV light is a serious threat. When the researchers modeled early Earth’s atmosphere—before oxygen appeared—they found that AGN radiation would likely destroy any chance of life forming. Without the shield of ozone, harmful rays would strike the surface unchecked.

In fact, on planets in older, more compact galaxies, the danger becomes extreme. In galaxies like NGC 1277, also called “red nugget relics,” stars orbit much closer to the central black hole. That means more planets could be exposed to lethal radiation. In contrast, galaxies like ours, with more spread-out stars, offer safer zones for life to evolve.

“In red nugget galaxies, everything is much closer together. So if the AGN turns on, the effects are stronger and reach more star systems,” says Eager-Nash.

That explains why the researchers estimate that AGN radiation could affect a much larger share of planets in compact galaxies than in spirals like the Milky Way or ellipticals like Messier-87.

The idea for this study began in an unexpected place: aboard the Queen Mary 2.

Ryan Hickox, a professor of physics and astronomy at Dartmouth, was heading to England for a sabbatical in 2023. To bring his dog along, he booked passage on the ocean liner. While aboard, he met Nathan Mayne, an astrophysicist from the University of Exeter giving talks during the voyage. The two quickly realized they shared an interest in modeling planetary atmospheres under extreme radiation.

That chance meeting led to collaboration. Sippy, working with Eager-Nash, used the PALEO model—originally designed to study solar flares from stars—to examine how AGN radiation impacts planet chemistry.

Using the programming language Julia, they input various oxygen levels and tracked the resulting changes in gas concentrations, radiation levels, and atmospheric chemistry over time. “It models every chemical reaction that could take place,” says Sippy.

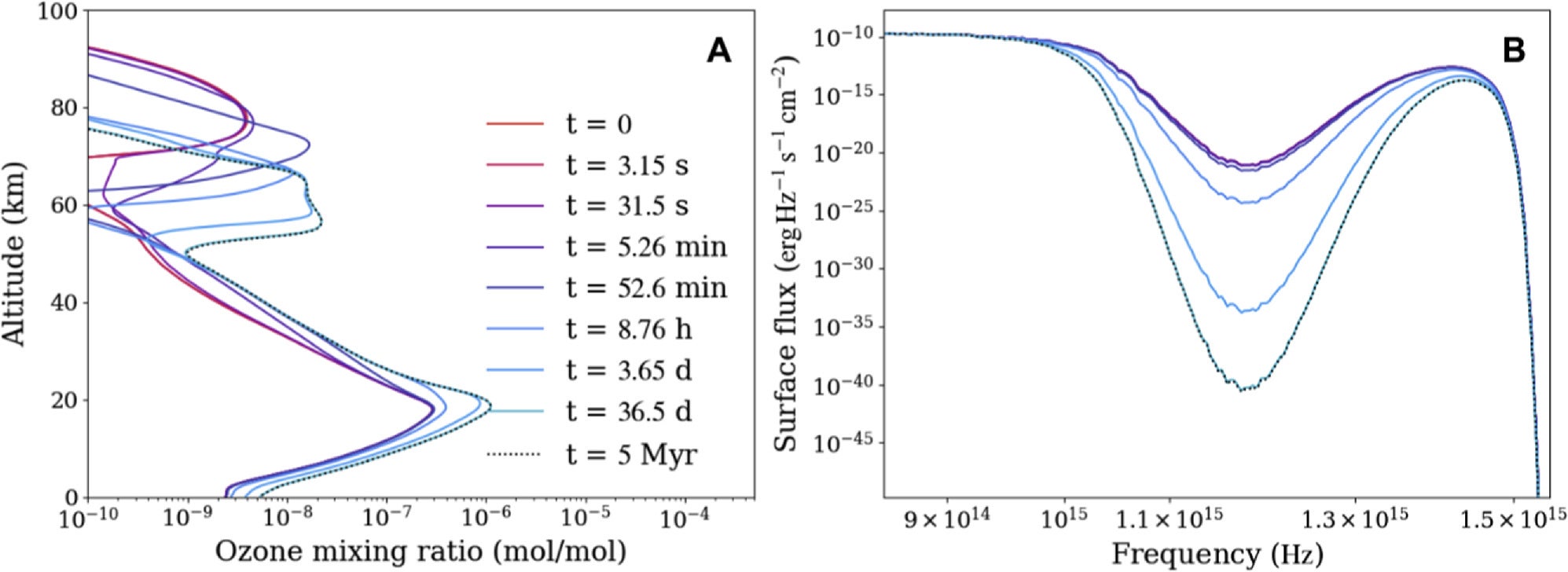

The results were striking. With high oxygen levels, a protective ozone layer could form in just a few days—even under intense AGN radiation. That meant some life could survive, even flourish, under what might seem like impossible conditions.

“We were surprised by how quickly ozone levels would respond,” says Eager-Nash.

The research highlights the importance of feedback loops in planetary habitability. Radiation alone doesn’t tell the whole story. The state of a planet’s atmosphere—and whether life has already started producing oxygen—can completely change the outcome.

“If a planet already has life and oxygen, AGN radiation may actually help keep it alive,” Sippy explains. “But if it doesn’t, that same radiation might stop life from ever taking hold.”

Helping to guide and review the work was McKinley Brumback, now a physics professor at Middlebury College. She studies neutron star systems, which also produce high-energy radiation but over much shorter time scales. AGNs may take millions of years to shift between active and inactive states. In contrast, neutron stars in X-ray binaries can change in days or months.

“A lot of the same physics applies to both systems,” Brumback says. “But AGNs operate on such long timescales, it’s a different challenge. My role was to help ensure the paper stayed readable for people outside of astrophysics. Thanks to Kendall’s excellent writing, it definitely was!”

This study adds a new layer to how scientists think about life in the universe. Instead of only viewing black holes as threats to life, they may also act as unlikely helpers. The key lies in timing, distance, and what stage a planet is in.

In galaxies where stars are packed closely together, the chances of AGN radiation reaching many planets go up. But if those planets have already started building oxygen-rich atmospheres, they might not just survive—they might thrive.

It’s a reminder that life’s journey is rarely a straight line. Sometimes, even the most destructive forces in the cosmos can help life find its way.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Black holes play a surprising role in the creation of life appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.