Knee cartilage usually wears down quietly. Over time, that loss can turn walking stairs into a daily calculation. Now a Stanford Medicine-led team reports that blocking a single age-linked protein helped old mice regrow knee cartilage and helped injured mice avoid a fast slide into arthritis. The same approach also pushed human knee tissue from joint replacements to make new, functional cartilage in the lab.

The work, published online in Science, is led by Stanford University researchers Helen Blau and Nidhi Bhutani. Blau is a professor of microbiology and immunology and directs the Baxter Laboratory for Stem Cell Biology. Bhutani is an associate professor of orthopaedic surgery.

Stanford instructor Mamta Singla and former Stanford postdoctoral scholar Yu Xin (Will) Wang led the study. Wang is now an assistant professor at the Sanford Burnham Institute in San Diego. Researchers from the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute also contributed.

Osteoarthritis affects about 1 in 5 U.S. adults and is linked to roughly 33 million patients nationwide. It is also expensive. Estimates put direct health care costs around $65 billion each year. Yet no approved drug slows or reverses cartilage breakdown. Treatment often focuses on pain control, activity changes and, when damage becomes severe, joint replacement.

The Stanford-led team targeted a protein called 15-PGDH, short for 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase. The researchers call 15-PGDH a “gerozyme” because it becomes more common with age and appears to push tissues toward decline.

Earlier work from Blau’s lab tied 15-PGDH to weaker regeneration in other tissues, including muscle. The enzyme breaks down prostaglandin E2, a molecule involved in repair signals. In that prior line of research, blocking 15-PGDH helped damaged tissues recover, including muscle, nerve, bone, colon, liver and blood cells.

Cartilage, though, has long been a stubborn exception. It has a limited ability to repair itself, even in young people. With aging, that repair capacity drops further, and damage often accumulates into osteoarthritis.

The cartilage most often lost in osteoarthritis is hyaline cartilage, also called articular cartilage. It is the smooth, glossy layer that helps joints glide. When joints face years of stress from aging, injury or excess body weight, cartilage cells called chondrocytes can shift into an inflammatory mode. They release signals that fuel swelling and they break down collagen, an important structural protein.

“Once collagen and other cartilage-building molecules fall, the tissue thins and softens. Pain and swelling often follow. Researchers have tried many repair strategies, including transplanted cells and scaffolds. But reliably restoring articular cartilage has remained difficult,” Singla told The Brighter Side of News.

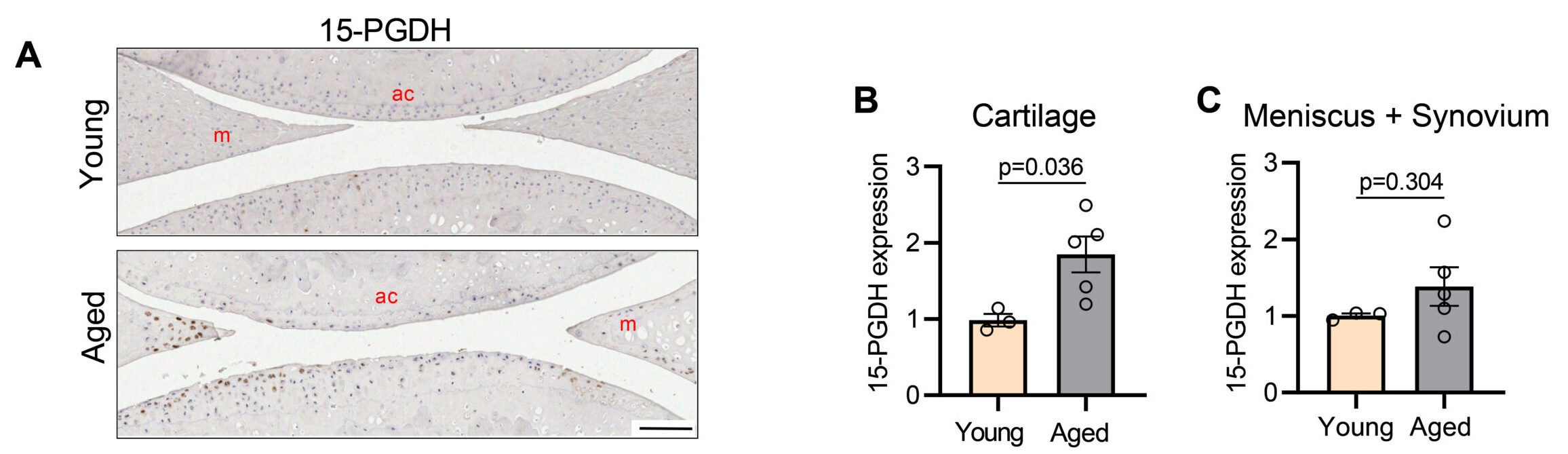

“Our team asked a simpler question first: does 15-PGDH rise in cartilage as joints age?” she continued.

In mice, it did. Levels of 15-PGDH in knee cartilage increased about twofold in older animals compared with young ones. Then the researchers tested what happened when they blocked the enzyme using a small-molecule inhibitor, SW033291, also described as PGDHi.

Old mice received the inhibitor either as body-wide injections into the abdomen or as local injections into the knee joint. In both approaches, cartilage that had become thinner with age thickened again across the joint surface.

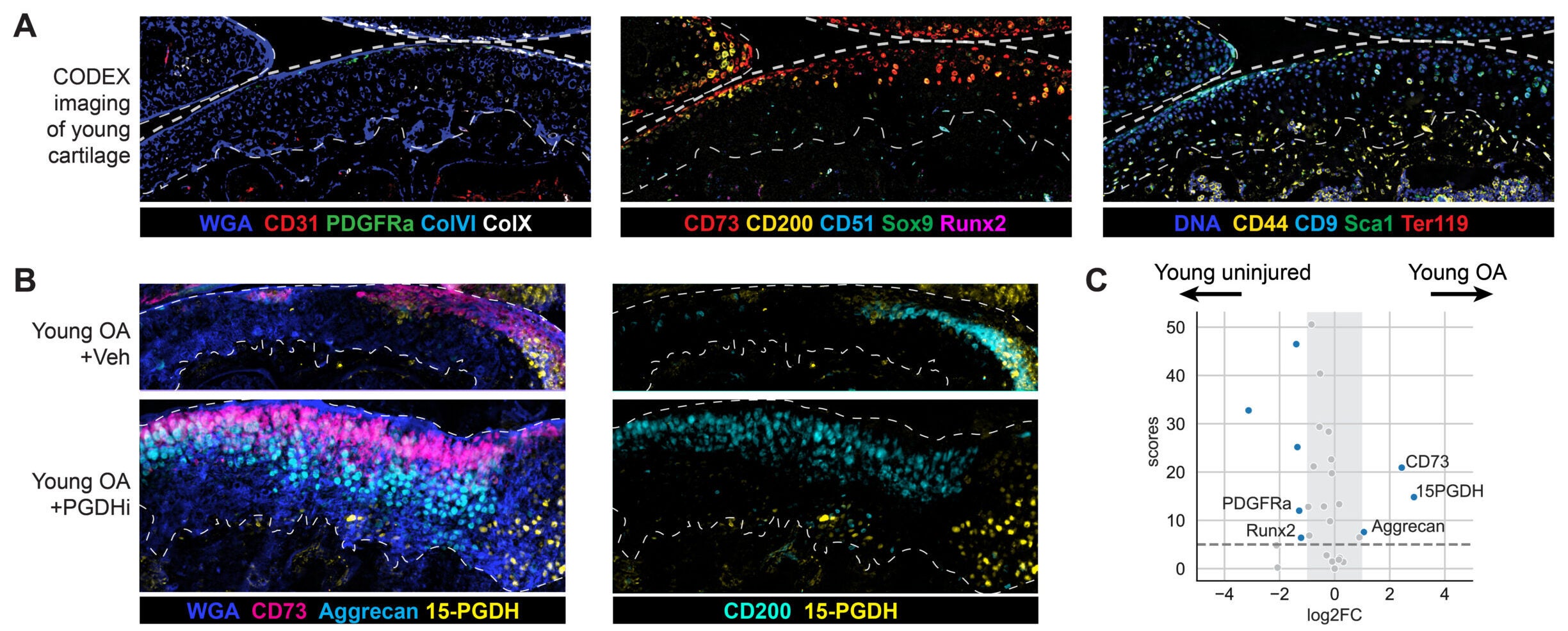

The team also checked what kind of cartilage returned. Not all repair tissue performs the same. Fibrocartilage, for example, is tougher and less suited for smooth joint motion. The treated mice showed signs of restored hyaline cartilage instead, including stronger signals for collagen type II and other markers linked to healthy joint cartilage.

“Cartilage regeneration to such an extent in aged mice took us by surprise,” Bhutani said. “The effect was remarkable.”

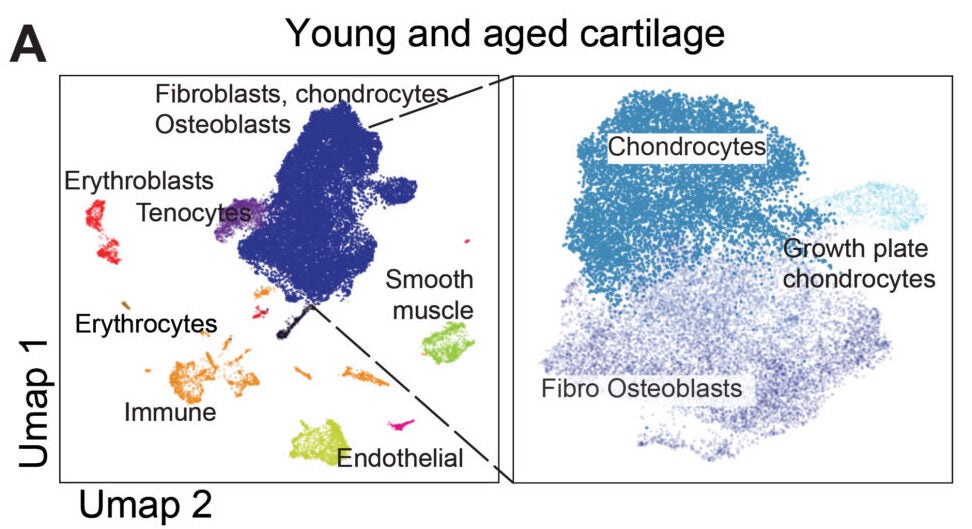

The researchers also tracked changes inside cartilage cells. They expected stem cells to drive the repair, as happens in some other tissues. Instead, they saw existing chondrocytes shifting into a more youthful pattern of gene activity.

“This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury,” said Helen Blau, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology. “We were looking for stem cells, but they are clearly not involved. It’s very exciting.”

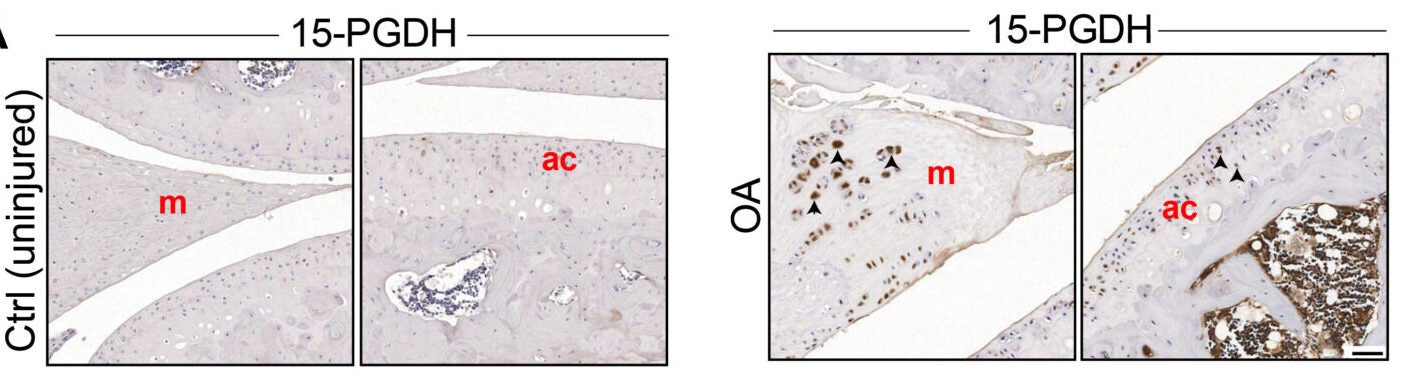

The team also tested an injury model designed to mimic a common human problem: an ACL tear. In people, even after surgical repair, about half develop osteoarthritis in the injured joint within about 15 years.

In mice, the researchers triggered an ACL-like rupture and then gave injections of the inhibitor into the joint twice a week for four weeks. The treated animals showed less cartilage damage and were less likely to develop osteoarthritis in the weeks after injury.

They also moved more normally and placed more weight on the injured leg than untreated animals. The group measured pain-related behavior in several ways, including gait tracking and sensitivity tests. Across those tests, treated mice showed less pain.

That finding matters because prostaglandin E2 is often linked with inflammation and pain. The inhibitor raises prostaglandin levels by stopping their breakdown. The team argues that the dose and setting may be the key.

“Interestingly, prostaglandin E2 has been implicated in inflammation and pain,” Blau said. “But this research shows that, at normal biological levels, small increases in prostaglandin E2 can promote regeneration.”

To test whether the mechanism might translate beyond mice, the researchers studied cartilage from people with osteoarthritis undergoing total knee replacement. In lab experiments, cartilage samples treated with the inhibitor for one week showed reduced activity of 15-PGDH and shifts in gene activity away from cartilage breakdown and fibrocartilage programs.

The treated tissue also showed signs of rebuilding cartilage matrix and improving mechanical stiffness, a property linked to how well cartilage can handle forces during movement.

The team’s broader message is that cartilage may not need an outside supply of new cells. A large pool of existing chondrocytes may be able to “reset” if a key age-linked brake is removed.

“The mechanism is quite striking and really shifted our perspective about how tissue regeneration can occur,” Bhutani said. “It’s clear that a large pool of already existing cells in cartilage are changing their gene expression patterns. And by targeting these cells for regeneration, we may have an opportunity to have a bigger overall impact clinically.”

An oral version of a 15-PGDH inhibitor is already in clinical trials aimed at treating age-related muscle weakness. Blau pointed to early safety progress in that effort and expressed hope for a cartilage-focused trial.

“Phase 1 clinical trials of a 15-PGDH inhibitor for muscle weakness have shown that it is safe and active in healthy volunteers. Our hope is that a similar trial will be launched soon to test its effect in cartilage regeneration. We are very excited about this potential breakthrough. Imagine regrowing existing cartilage and avoiding joint replacement.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and several foundations and Stanford programs. Blau, Bhutani and other co-authors are inventors on patent applications held by Stanford University related to 15-PGDH inhibition in cartilage and tissue rejuvenation licensed to Epirium Bio. Blau is a co-founder of Myoforte/Epirium and holds equity and stock options in the company.

If these findings hold up in human trials, cartilage loss may no longer look like a one-way path to joint replacement. A local injection could one day help older adults rebuild articular cartilage instead of only managing pain. That could extend the working life of knees and hips, especially for people trying to stay active as they age.

The injury results also point to a future role in sports medicine. After an ACL tear, the long-term threat is often osteoarthritis, not the initial injury alone. A short course of joint injections after injury, or after surgery, could reduce later cartilage breakdown and help people keep mobility for decades.

For research, the biggest shift may be conceptual. The study suggests cartilage can recover through a change in existing cell behavior, not by relying on stem cells. That could widen the search for arthritis drugs toward “reprogramming” signals inside chondrocytes, with clearer targets and faster testing in human tissue.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Blocking a key aging enzyme helps regrow knee cartilage, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.