A new scientific breakthrough may soon offer hope for people affected by Alzheimer’s disease. A group of researchers in Spain has developed a drug candidate that could help fight the condition at its core—not by focusing on plaques in the brain like most previous treatments, but by stopping the damaging inflammation behind them.

Alzheimer’s is the leading cause of dementia worldwide. In Spain alone, more than 800,000 people are living with the disease. It has no cure, and current drugs offer only limited help for people in the early stages. But recent discoveries suggest that inflammation in the brain might be more than just a side effect—it may be a key driver of the disease itself.

A research team from the University of Barcelona believes it has found a way to block that inflammation and protect the brain using a new kind of molecule.

The new drug targets an enzyme called soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH). This enzyme breaks down molecules known as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), which help reduce inflammation and protect nerve cells. Once broken down by sEH, these EETs become compounds that promote inflammation. Scientists found that in both people with Alzheimer’s and mouse models of the disease, the amount of sEH was unusually high, especially in the hippocampus—an area critical for memory.

Blocking sEH helps the brain keep more of its natural anti-inflammatory compounds. This approach could be especially useful because it doesn’t focus on just one part of the disease. Alzheimer’s involves a complex mix of problems—beta-amyloid plaques, tangled tau proteins, loss of nerve cells, and harmful immune responses. By lowering brain inflammation and supporting nerve cell health, sEH inhibitors could treat several of these problems at once.

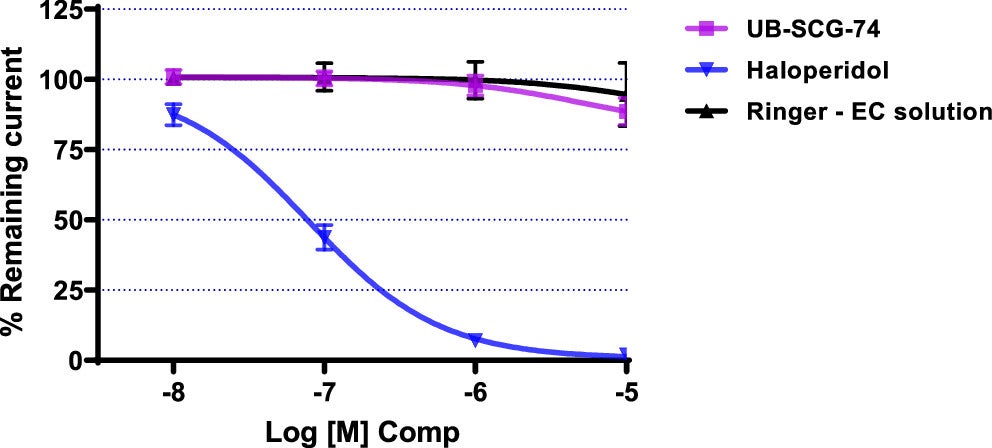

That’s why researchers turned their focus to this enzyme and developed a new compound, called UB-SCG-74. The results so far look promising.

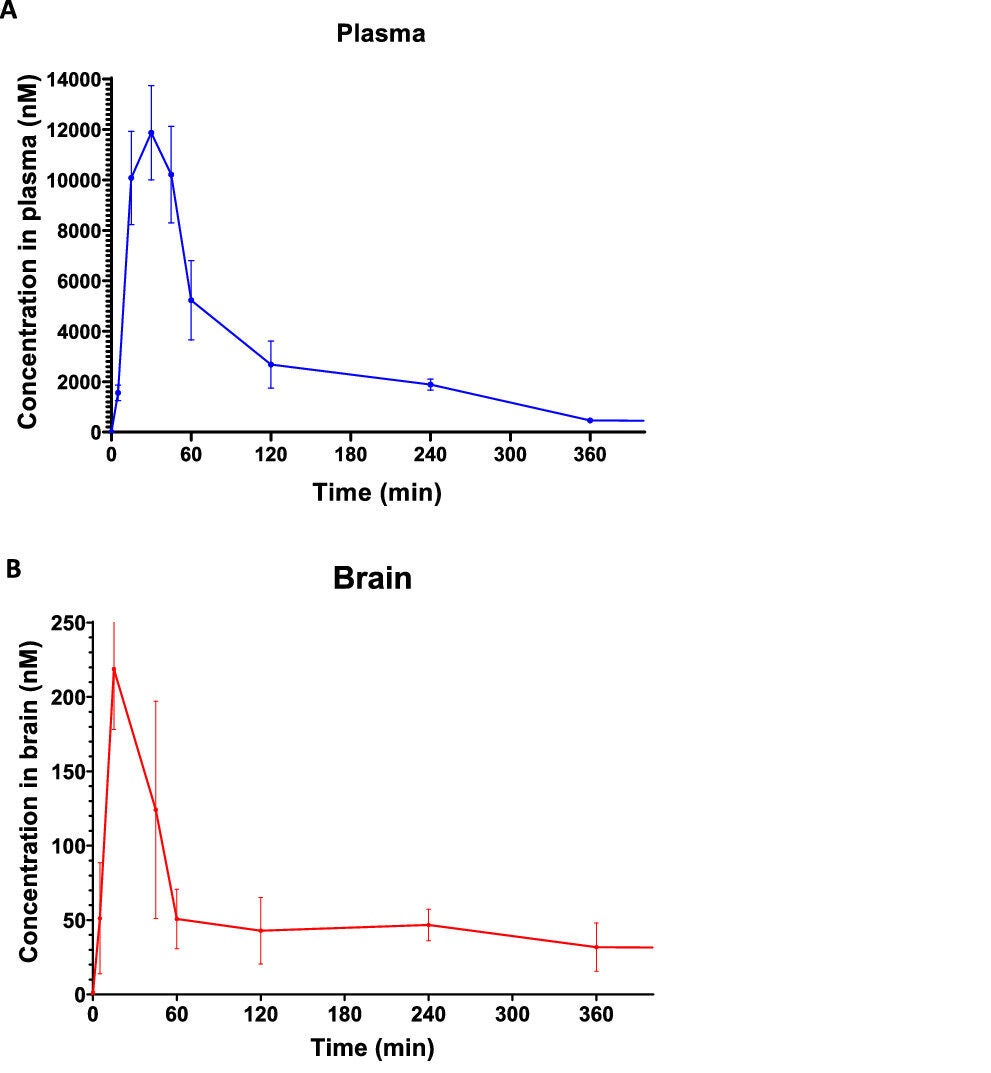

The journey started with an earlier version of the molecule, named UB-SCG-51. It showed good brain penetration and could block sEH effectively. Tests in mice with Alzheimer’s showed it did more than just ease inflammation—it also slowed down cell death, cut back on toxic protein buildup, and improved brain function. But the team wanted to go further. They created a modified version, UB-SCG-74, which is more easily absorbed in the body and lasts longer.

Related Stories

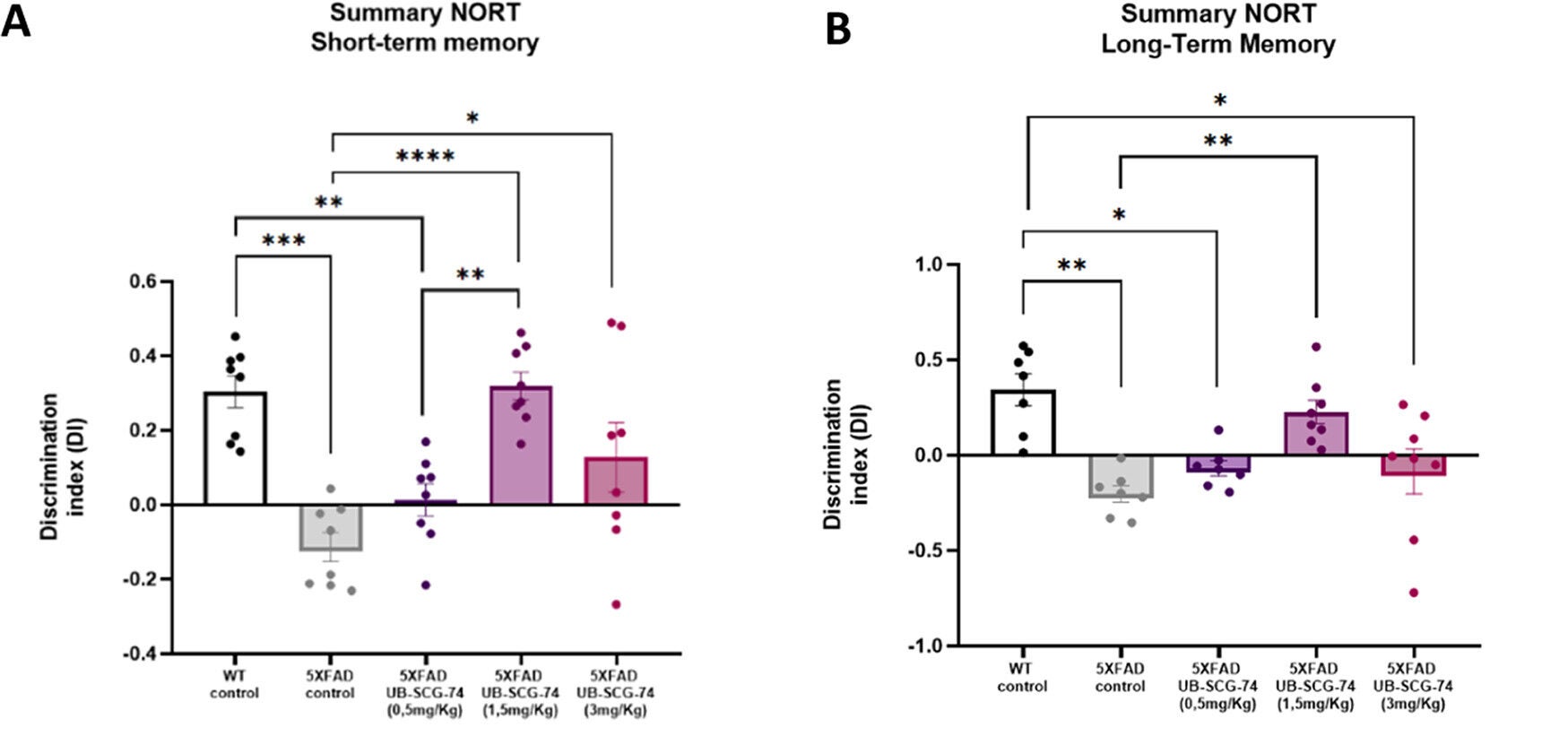

UB-SCG-74 was tested in 5XFAD mice—animals that quickly develop symptoms similar to human Alzheimer’s. The treated mice showed better memory, stronger synaptic plasticity (the ability of brain cells to communicate), and fewer signs of brain damage. Even more exciting, these benefits lasted for a full month after the treatment ended. That long-lasting impact hints that the drug might not just mask symptoms, but actually change the disease’s course.

UB-SCG-74 outperformed both donepezil, a commonly used Alzheimer’s drug, and ibuprofen, a known anti-inflammatory. No signs of toxicity were found in safety tests, which supports moving the compound toward preclinical development.

For decades, scientists have focused on clearing amyloid plaques from the brain as a way to treat Alzheimer’s. But that strategy has often failed. In the past ten years, many plaque-targeting drugs have not shown enough benefit to make it to patients.

The team behind UB-SCG-74 believes that tackling brain inflammation could be a more powerful way to protect the brain. “Strategies that have been tried unsuccessfully over the past ten years have specifically targeted beta-amyloid accumulation and plaque formation in the brain, but there is evidence that neuroinflammation is a major cause of Alzheimer’s disease,” the study authors wrote.

The new compound works by restoring the balance of inflammatory molecules. It not only lowers harmful cytokines but also raises levels of molecules that reduce inflammation. This wide-reaching impact on many pathways at once may explain why the treatment helped preserve neurons and protect brain function.

Mercè Pallàs, one of the lead researchers and a scientist at the University of Barcelona and CIBERNED, says that this anti-inflammatory action is tied to improved blood flow in the brain as well.

EETs play a role in keeping blood vessels healthy, so stopping sEH allows the brain to maintain better circulation. That could offer protection against strokes or oxygen loss, which often worsen Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Mice treated with UB-SCG-74 didn’t just perform better on memory tasks. Their brain cells also looked healthier under the microscope. Dendrites—the tiny branches that allow neurons to connect—were preserved. The structure of neural networks remained intact. These findings point to more than temporary relief. They suggest the drug may be able to stop or even reverse damage in the brain.

Santiago Vázquez, another lead author from the University of Barcelona, says this result is crucial. “This could help preserve neuronal function and reduce neuronal death associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” he noted. The fact that these effects lasted even after treatment stopped suggests that the drug changes how the disease unfolds, not just how it feels.

Despite the strong results in mice, much work remains before this compound can be used in humans. Drug development is a slow and careful process. Researchers must complete further lab tests, followed by clinical trials involving real patients. These trials will need to confirm both the safety and the effectiveness of the drug in people with Alzheimer’s.

The University of Barcelona has licensed the patent for UB-SCG-74 to a U.S. pharmaceutical company, which will lead the next steps in development. Pallàs and Vázquez are working with the company as consultants. Their goal is to ensure the project stays focused on fighting neuroinflammation and moving the drug forward.

They aren’t alone in this work. Scientists from the Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona, the August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute, the Centre for Biomedical Research Network (CIBERNED), and the University of Bonn are also part of the research effort. The study was published in ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science.

This seven-year project shows how rethinking Alzheimer’s could open new doors. Instead of trying to remove plaques after they form, it may be more effective to protect the brain before they cause too much harm. That’s where sEH inhibitors like UB-SCG-74 could make a difference.

Blocking this enzyme helps keep inflammation in check, supports blood flow, prevents nerve cell death, and improves memory—all at the same time. This broad, multitarget approach could become a new standard in treating Alzheimer’s, especially since past single-target strategies have fallen short.

If future trials confirm these benefits in humans, this treatment might not just slow the disease—it could change the way it develops entirely. That kind of shift would bring much-needed hope to families affected by dementia and move medicine a step closer to one day curing Alzheimer’s disease.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Breakthrough Alzheimer’s drug blocks brain inflammation and reverses damage appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.