For many people, spotting blood in the urine is often the first warning sign of bladder cancer. But for those with color vision deficiency, commonly called colorblindness, that signal can easily go unnoticed. Now, a study from Stanford Medicine shows that missing this visual cue can have serious consequences for survival.

Researchers analyzing health records found that people with bladder cancer who are also colorblind face a 52 percent higher risk of dying over 20 years than patients with normal vision. The findings suggest that delays in noticing blood in urine may lead to later-stage diagnoses and poorer outcomes.

“I’m hopeful that this study raises some awareness, not only for patients with colorblindness, but for our colleagues who see these patients,” said Ehsan Rahimy, MD, adjunct clinical associate professor of ophthalmology and senior author of the study.

The lead author of the study is Mustafa Fattah, a medical student at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Color vision deficiency affects roughly 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women. The most common types make it difficult to distinguish red from green. This can create everyday challenges such as interpreting traffic lights, matching clothes, or judging whether meat is fully cooked. Bladder cancer is also more common in men, who are about four times more likely to develop it than women. In 2025, an estimated 85,000 Americans were diagnosed with the disease.

Previous small studies suggested that colorblindness might delay detection of cancers where early signs involve blood in urine or stool. A 2009 study of 200 men with bladder cancer found that those with color vision deficiency were diagnosed at more advanced stages than peers with normal vision. Another study in 2001 showed photos of urine, stool, and saliva to participants. People with normal vision correctly identified blood 99 percent of the time, while those with colorblindness were correct only 70 percent of the time.

Intrigued by these findings, Rahimy’s team sought to determine whether colorblindness ultimately affected long-term survival in bladder cancer and colorectal cancer.

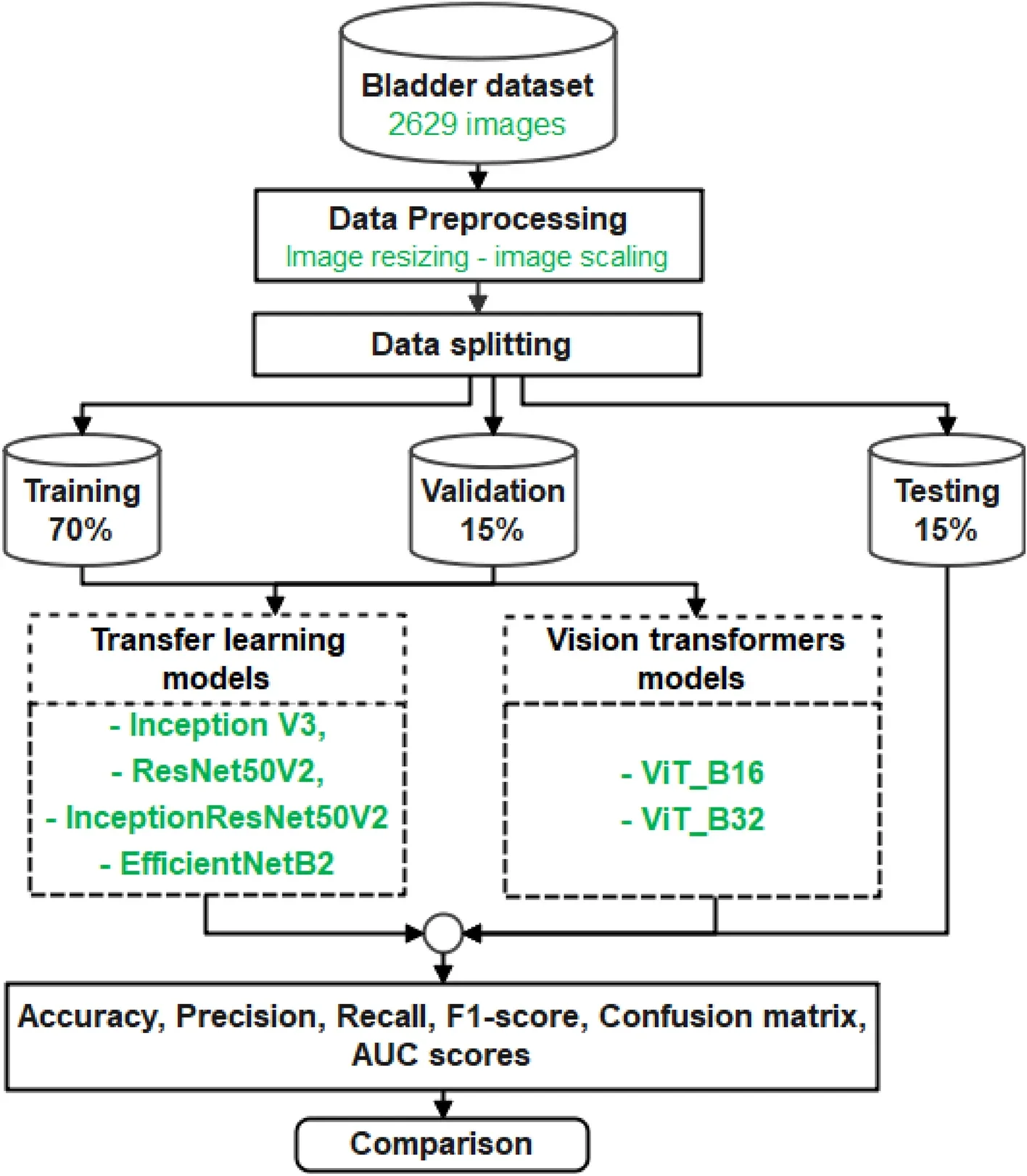

The researchers used TriNetX, a research platform that aggregates electronic health records from around the world. The platform includes roughly 275 million de-identified patient records, allowing scientists to identify rare combinations, such as colorblindness paired with bladder or colorectal cancer.

Starting with about 100 million U.S. patient records, the team found 135 patients diagnosed with both colorblindness and bladder cancer and 187 with both colorblindness and colorectal cancer. Each patient group was matched to a control group of similar age, sex, and health characteristics but with normal vision.

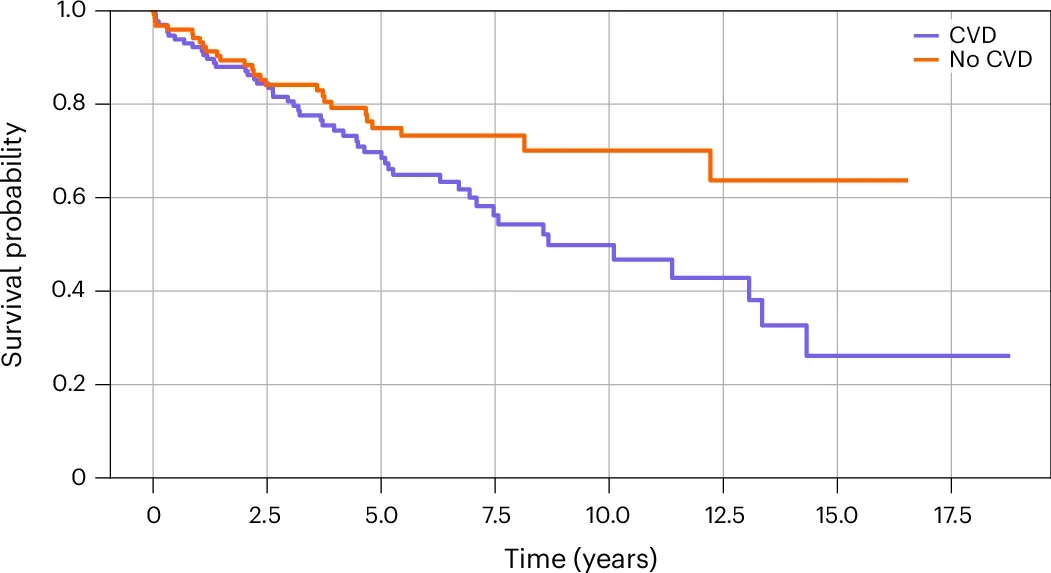

The results were striking. Patients with bladder cancer and color vision deficiency had lower survival rates than those with normal vision, with a 52 percent higher overall mortality risk over 20 years. Rahimy explained, “That was our working hypothesis, based on the previous studies.”

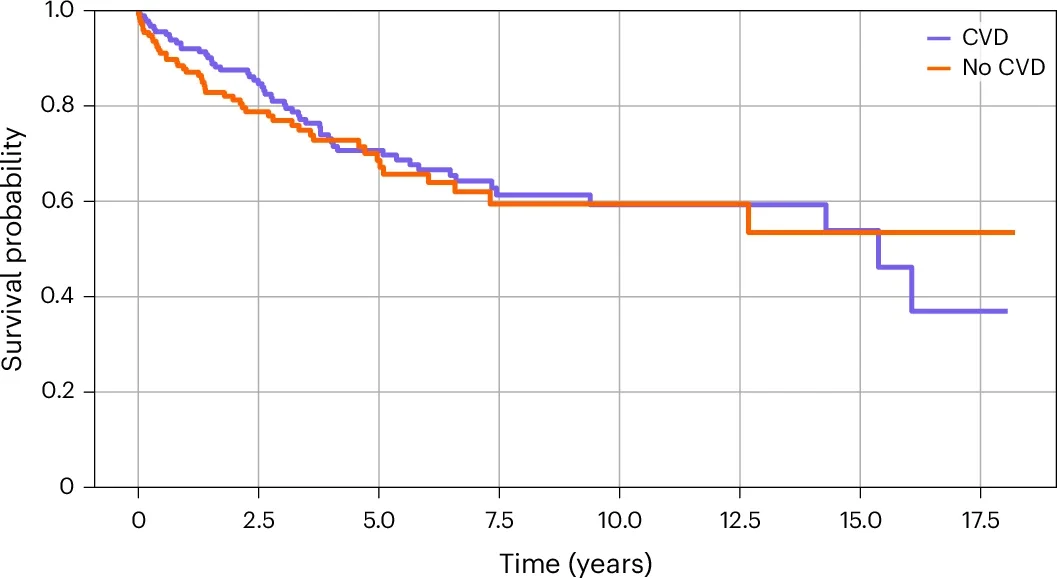

The researchers expected similar results for colorectal cancer, but none appeared. Survival rates for patients with and without color vision deficiency were statistically similar. Colorectal cancer often presents with other symptoms besides blood in the stool.

Nearly two-thirds of patients initially report abdominal pain, and more than half notice changes in bowel habits. Bladder cancer, in contrast, usually shows blood in the urine as the first noticeable sign for 80 to 90 percent of patients.

Regular colorectal cancer screening for people aged 45 to 75 may also reduce reliance on color perception for early detection. Rahimy said, “There’s much more focus on catching colorectal cancer at an early age and much more public awareness.”

Color vision deficiency itself does not make bladder cancer more aggressive. Instead, it may influence how quickly patients notice symptoms and seek care. Missing early warning signs could delay diagnosis and treatment, ultimately affecting survival.

“Most people with color vision deficiency are typically functioning fine. Many may not even know they have it,” Rahimy said. The study relied on ICD-10 diagnostic codes in health records, meaning some colorblind patients were likely counted as having normal vision. The true impact may therefore be even greater.

The study highlights the importance of awareness for both patients and healthcare providers. People with color vision deficiency might benefit from routine urine tests at annual checkups and even assistance from family members in checking for blood.

Rahimy said, “If you don’t trust yourself to know that there’s a change in the color of your urine, it could be worth having a partner or somebody you live with periodically checking it.”

Physicians may also begin asking patients about color vision deficiency during screenings. Some urologists and gastroenterologists have said they had never considered it as a factor in cancer diagnosis. Awareness alone could improve early detection, helping patients receive treatment when outcomes are better.

The study illustrates how sensory differences can influence health outcomes. Color vision deficiency is common, especially in men, and may shape the way patients notice early warning signs of disease. By accounting for such differences, doctors could tailor education, screening, and monitoring strategies to improve outcomes.

For colorectal cancer, the study’s findings are reassuring. Screening methods such as colonoscopies and stool tests, which do not rely on a patient’s color perception, may help detect disease early regardless of vision. The research raises new questions about how other sensory differences could affect disease detection and survival. Future studies may investigate how vision or other senses shape the timing of diagnosis and inform clinical recommendations.

These findings could change the way patients with color vision deficiency approach healthcare. Routine urine tests and early screenings may be particularly important for these individuals.

Doctors might incorporate questions about color vision into screening protocols, helping patients catch early warning signs before cancers progress. Greater awareness among healthcare providers and patients could reduce delayed diagnoses and improve long-term survival for bladder cancer.

Additionally, this study highlights the broader need to consider human sensory differences when designing screening, education, and public health initiatives.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

The original story “Colorblindness linked to higher risk of delayed bladder cancer detection” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Colorblindness linked to higher risk of delayed bladder cancer detection appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.