Life on Earth began simply. For billions of years, tiny microbes ruled the planet. Then, one day in deep time, something changed. Cells gained a nucleus, built inner compartments and learned to produce energy in new ways. That leap gave rise to algae, fungi, plants, animals and eventually humans.

A new international study now says this transformation began far earlier and unfolded more slowly than scientists once believed. The work, led by the University of Bristol and published in the journal Nature, traces the rise of complex cells through their genes instead of rare fossils. It reveals a drawn-out story that started nearly 3 billion years ago, long before Earth had much oxygen to breathe.

You might be surprised to learn that the nucleus likely formed first. The cell’s so-called power plant, the mitochondrion, appears to have arrived later.

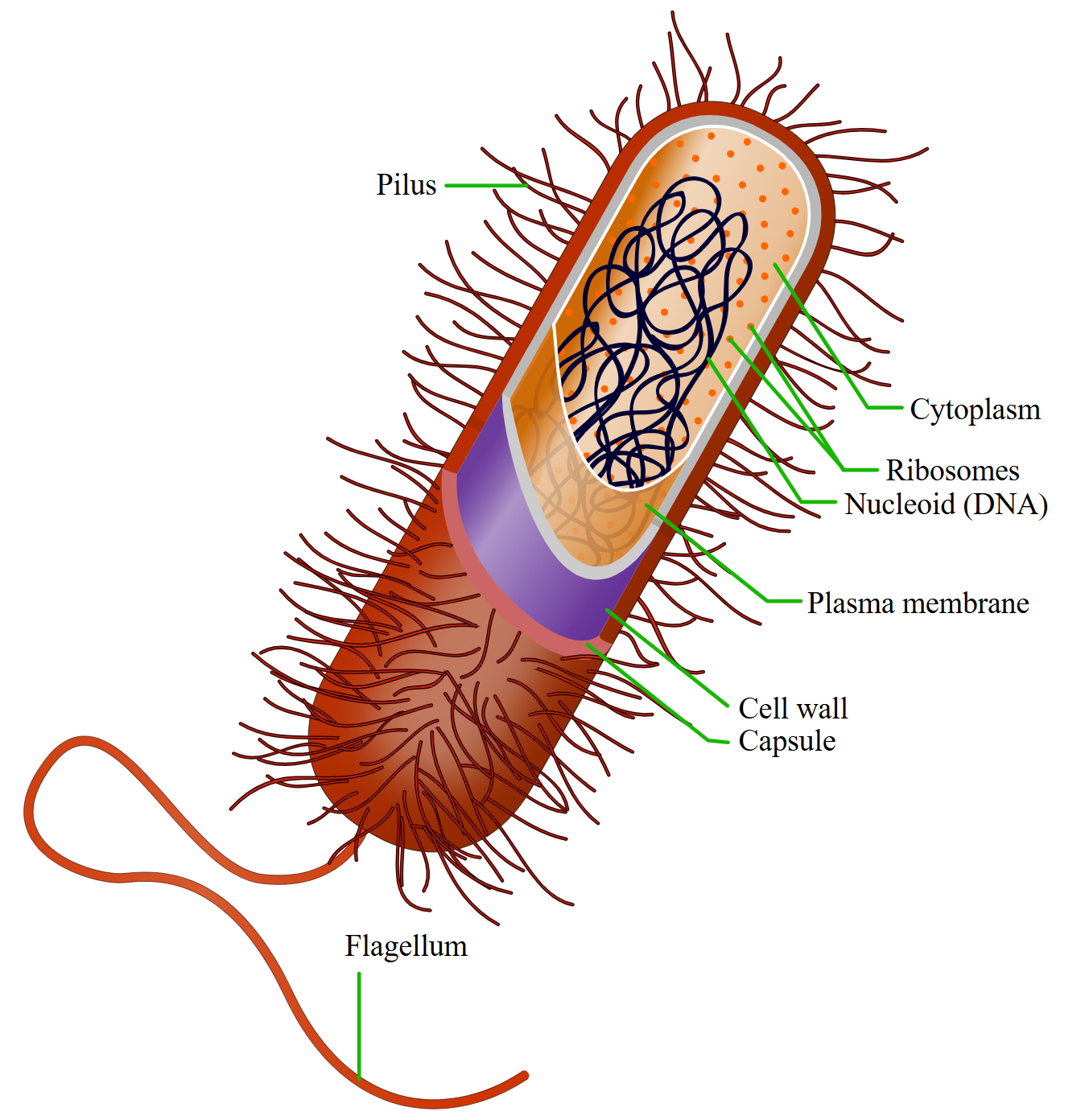

Earth itself is about 4.5 billion years old. The first life emerged more than 4 billion years ago. For ages after, only two kinds of cells existed, bacteria and archaea. Together, they are called prokaryotes.

“Prokaryotes were the only life on Earth for hundreds of millions of years,” said co-author Anja Spang of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. “Then, much later, complex cells appeared.”

Those complex cells are known as eukaryotes. They store DNA in a nucleus. They have inner membranes that sort cargo and break down waste. They rely on mitochondria to make energy. Every animal and plant belongs to this group.

Scientists have long argued over how eukaryotes formed. Some have said the mitochondrion sparked everything. Others believed complexity came first.

Until now, most of the debate relied on guesses.

“Previous ideas were largely speculation,” said Davide Pisani, professor of phylogenomics at the University of Bristol. “There are no clear fossils from this stage. Estimates varied by a billion years.”

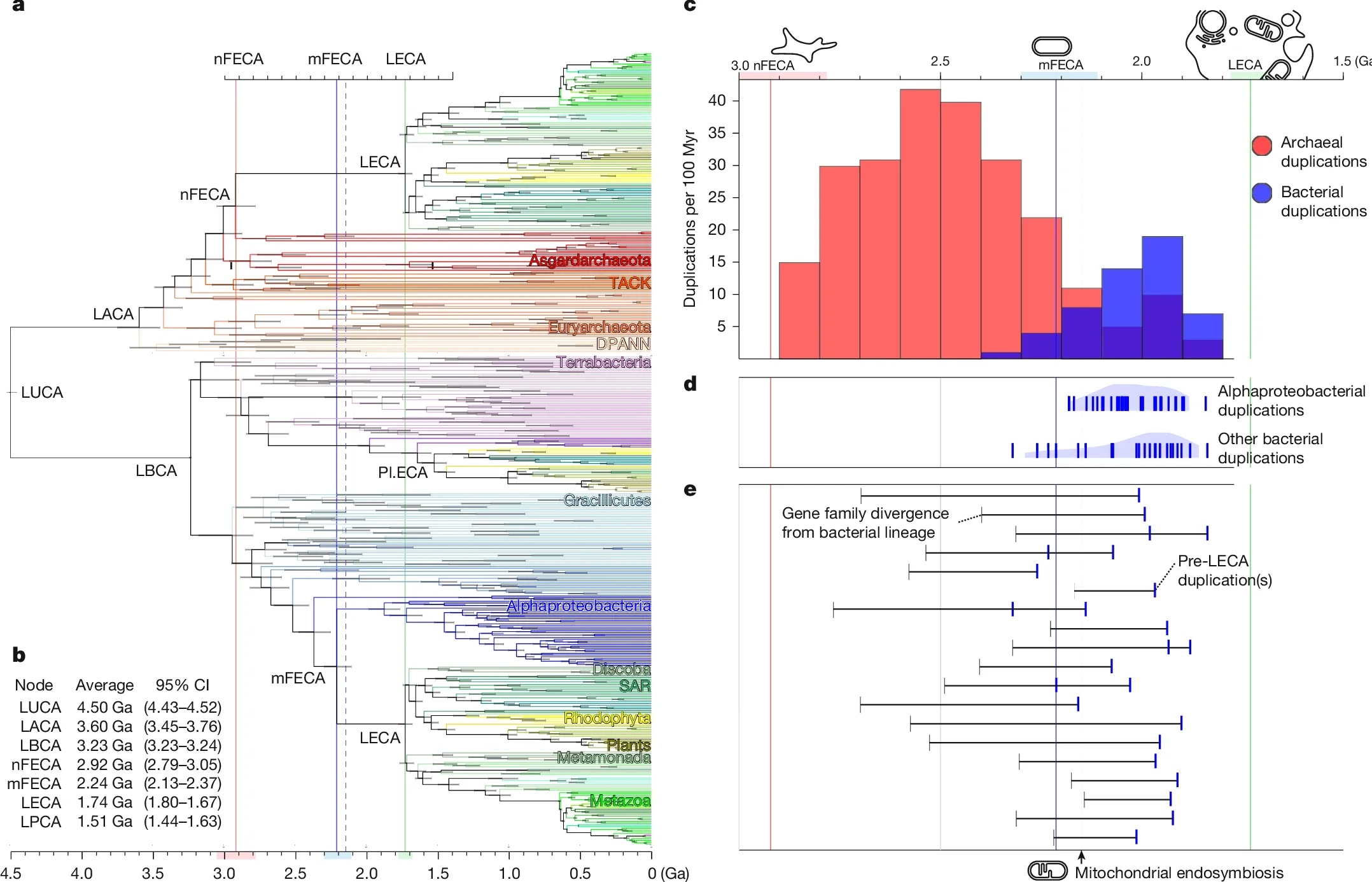

To solve the puzzle, the research team turned to genetic clocks. These tools estimate when genes split or duplicate based on small changes in DNA sequences.

The scientists analyzed 135 families of genes that existed before the last shared ancestor of all eukaryotes. They compared those genes across hundreds of living species and matched them with known fossil dates.

“We built a time map of life,” said co-lead author Tom Williams of the University of Bath. “Then we placed each gene family onto that map.”

What they found reshapes the timeline.

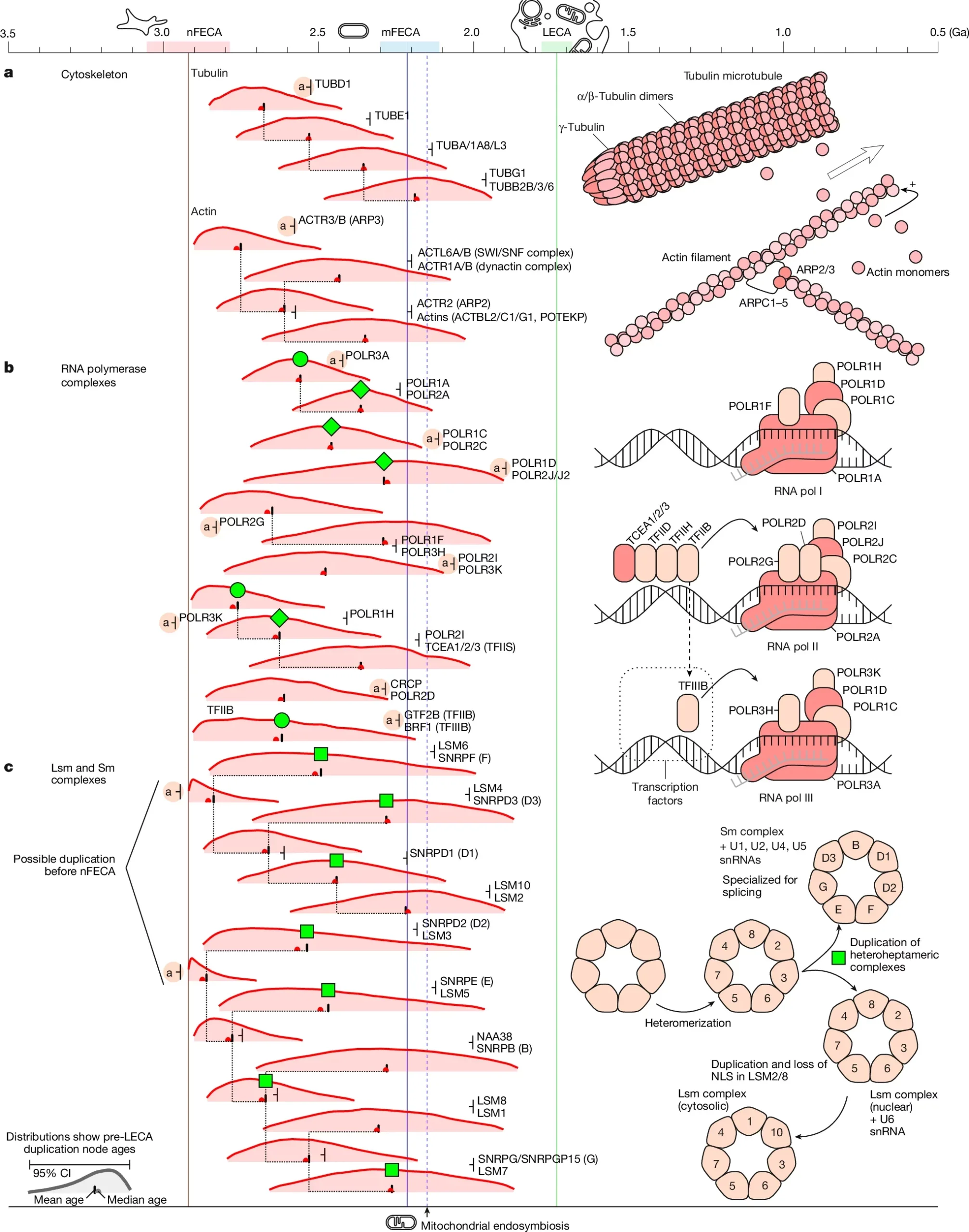

Genes that came from archaea began duplicating early. Many date back to between 3 and 2.7 billion years ago. These genes helped form the skeleton of the cell, the network that gives it shape and allows movement.

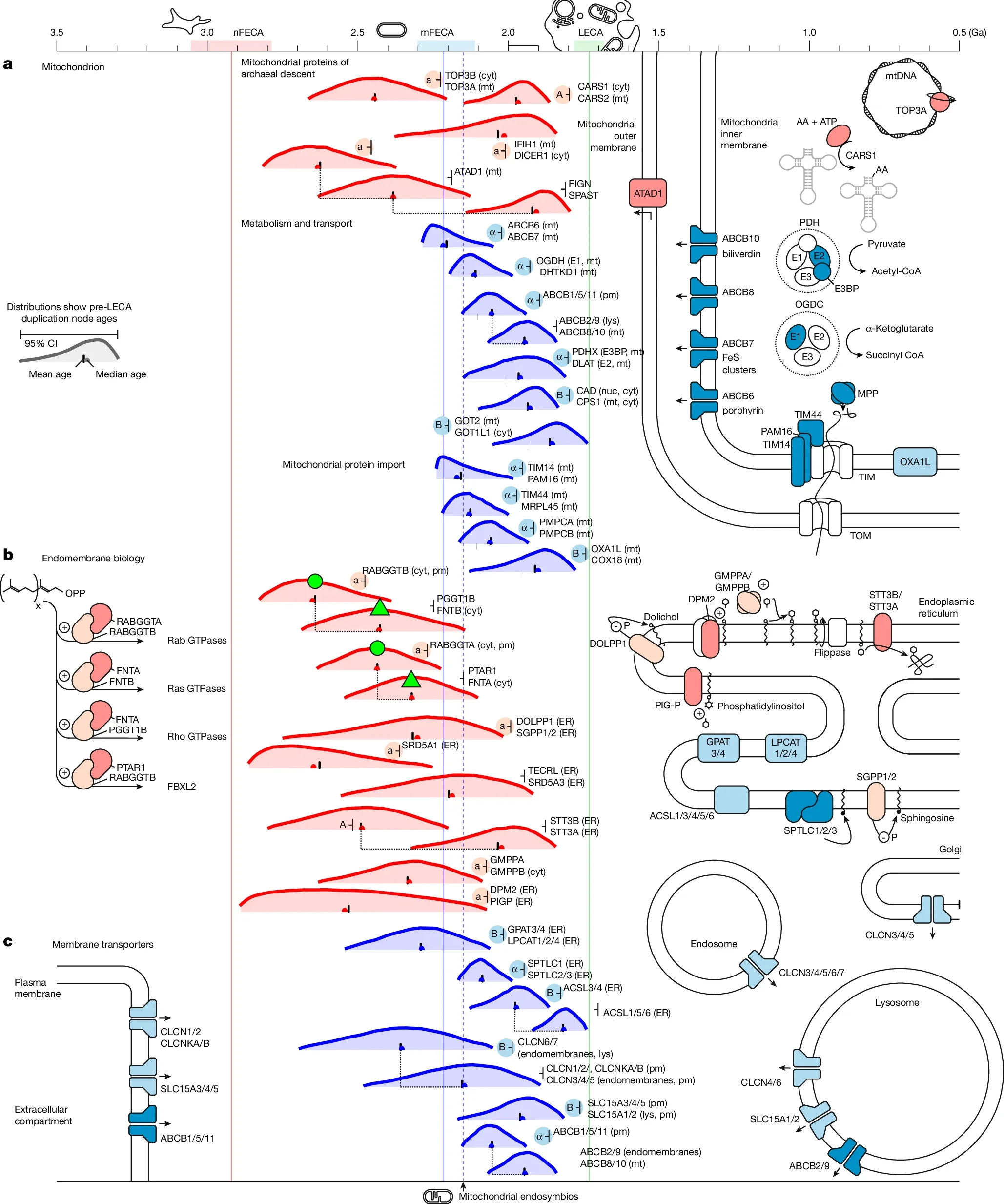

In contrast, genes from bacteria began duplicating later, about 2.2 billion years ago. These included genes that help proteins enter the mitochondrion and fuel energy-making reactions.

This pattern suggests that an archaeal host cell grew complex on its own before merging with a bacterium that later became the mitochondrion.

“The host was not simple when that merger happened,” said lead author Christopher Kay of the University of Bristol. “It already had a strong framework inside.”

The nucleus appears to be one of those early features. Genes tied to RNA processing multiplied over a long span, from about 2.9 to 1.9 billion years ago. Genes tied to RNA-making enzymes also duplicated early.

Together, these changes point to a growing gap between copying DNA and building proteins. That gap is one hallmark of a true nucleus.

The cell’s inner scaffolding also took shape early. Actin genes, which help form cables in cells, duplicated around 2.8 billion years ago. Tubulin genes, which help build tracks that carry cargo, split soon after.

These were not small upgrades. They tell a story of a cell that already moved, sorted materials and contained space.

“This was not a blank container,” Kay said. “It was already organized.”

The big surprise came when the mitochondrion entered the story.

Based on early bacterial gene activity, the team believes the merge began about 2.2 billion years ago. That date falls just after Earth’s first major rise in oxygen, known as the Great Oxidation Event.

Philip Donoghue of the University of Bristol explained the meaning. “The archaeal ancestor started becoming complex in oceans with no oxygen. Mitochondria arrived only when oxygen began to rise.”

Genes linked to energy work inside the mitochondrion also duplicated early. So did genes that help move proteins into the organelle.

At the same time, most other bacterial genes appeared later. That makes it unlikely there were earlier mergers with other bacteria.

This was a single, turning-point event.

The data did not match older theories. So the team proposed a new one, known as CALM. It stands for “Complex Archaeon, Late Mitochondrion.”

In this view, complexity built up slowly inside an archaeal cell. Only later did a bacterium take up residence and become the mitochondrion.

“The process stretched across almost a billion years,” said Gergely Szöllősi of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. “It was gradual, not sudden.”

The team credits teamwork across many fields, from fossil studies to genetics.

“It took palaeontology, evolutionary trees and molecular work together,” Kay said. “No single approach could solve it.”

This research changes how life’s greatest leap is understood. It shows that complex life did not wait for oxygen to rise and did not hinge on a single accident. Instead, slow change built the stage for a rare partnership.

For scientists, the work offers a clearer path for testing how cells evolve. It may guide future experiments in synthetic biology, where researchers try to build cell systems from scratch.

For the rest of us, it deepens the sense of wonder. Your cells reflect a long journey, shaped by ancient seas, silent chemistry and a meeting between strangers that changed the world.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Complex life developed much earlier than previously thought, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.