Caltech astronomer Mansi Kasliwal and her colleagues were not expecting to chase a mystery that blurred the line between a supernova and a kilonova. Yet that is where the evidence has led after an unusual August 2025 alert from the LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA gravitational-wave network and a rapid optical search with Caltech’s Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory.

The central question is simple to state and hard to answer: did astronomers witness a rare, linked chain of explosions, or did two unrelated events happen to overlap in the same patch of sky? In a new study in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Kasliwal’s team argues the data are unusual enough to keep both possibilities on the table.

Multimessenger astrophysics combines signals from different “messengers,” including light, gravitational waves, neutrinos, and cosmic rays. For decades, the Sun and Supernova 1987A stood out as the best-studied cases seen in both light and neutrinos. The field changed in 2017 with GW170817, a neutron star merger that produced both gravitational waves and a bright, fast-evolving flash of light called a kilonova.

On Aug. 18, 2025, the LIGO detectors in Louisiana and Washington, along with Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan, registered another candidate: S250818k. The signal looked like a merger involving unusually low-mass compact objects. If the event was real and not instrumental, at least one of the colliding bodies appeared lighter than the Sun with more than 99 percent confidence. The “chirp mass,” a key parameter that shapes the gravitational-wave signal, was about 0.87 times the Sun’s mass.

That low mass is the problem. Normal stellar evolution does not easily produce neutron stars below about a solar mass. The early automated analysis also raised doubts. It reported a false-alarm rate of 2.1 per year and a “terrestrial” probability of 70 percent, meaning the network initially judged noise to be more likely than a real astrophysical event.

Still, experience has taught gravitational-wave astronomers to be cautious about early numbers. Offline re-analysis can strengthen or weaken candidates. This one looked odd enough to justify a search for light, especially because it could be the strongest subsolar-mass merger candidate yet.

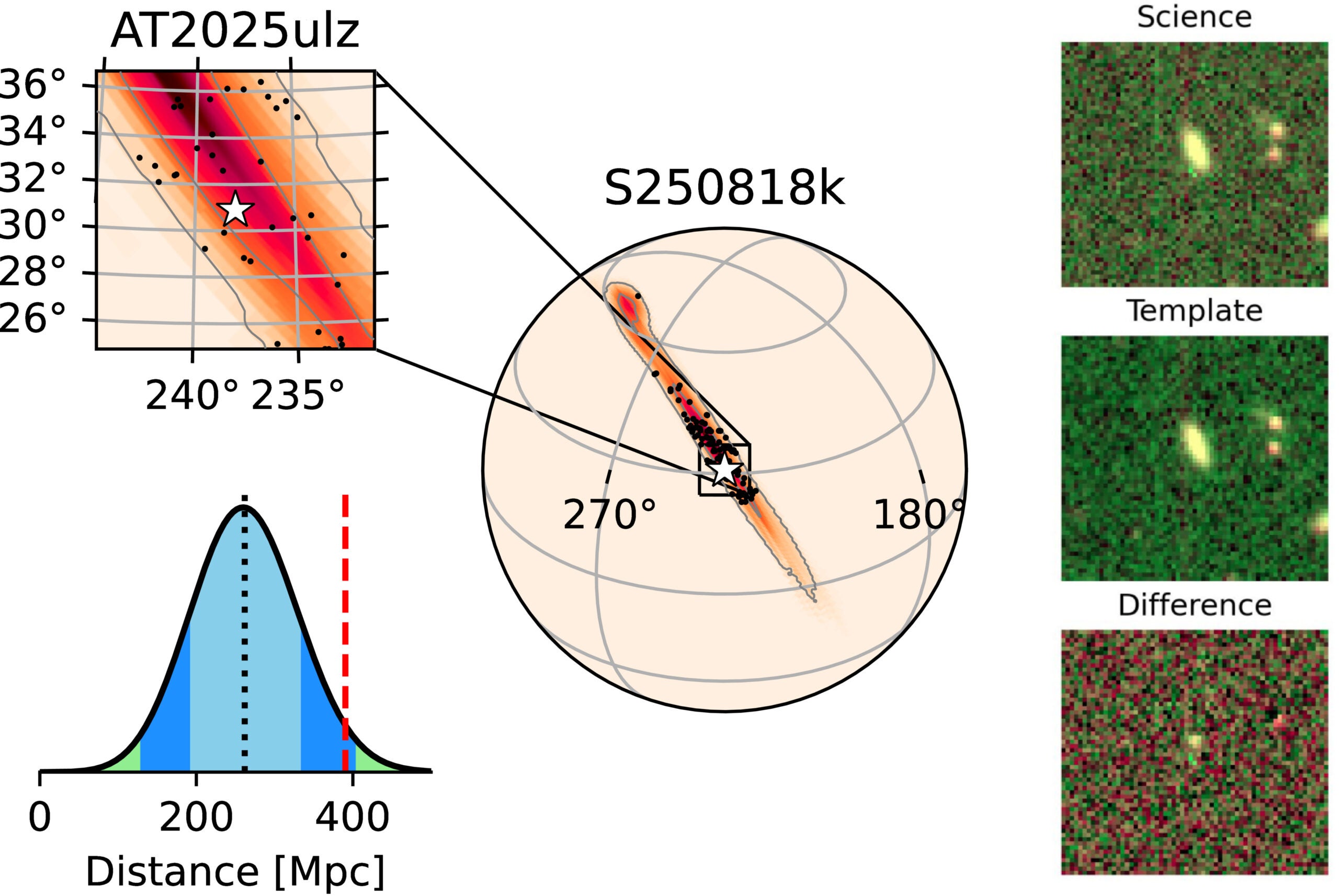

Within hours, the Zwicky Transient Facility swung toward the broad sky region where the merger might have occurred. ZTF began imaging at 04:02 UTC, about 2.7 hours after the estimated merger time. Its “Target of Opportunity” strategy took three 300-second exposures per field in a g, r, then g pattern. That approach helped capture both color and fading behavior.

Over the first 36 hours, the survey covered 369.7 square degrees, about a third of the gravitational-wave localization region. The images reached a median depth near magnitude 21.9 in both g and r bands. The volume of alerts was immense. Over 72 hours, searches produced 30,061 transient alerts inside the 95 percent confidence contour for S250818k. Astronomers manually reviewed 109 of the most promising candidates.

Only one source consistently stood out. First labeled ZTF 25abjmnps and later named AT2025ulz by the International Astronomical Union Transient Name Server, it looked unusually red and sat in a plausible host galaxy. Spectra of the host yielded a redshift of 0.0848, placing it about 399 megaparsecs away, roughly 1.3 billion light-years. That distance was within two standard deviations of the gravitational-wave estimate. Independent searches, including the Pan-STARRS1 survey, did not find a better match.

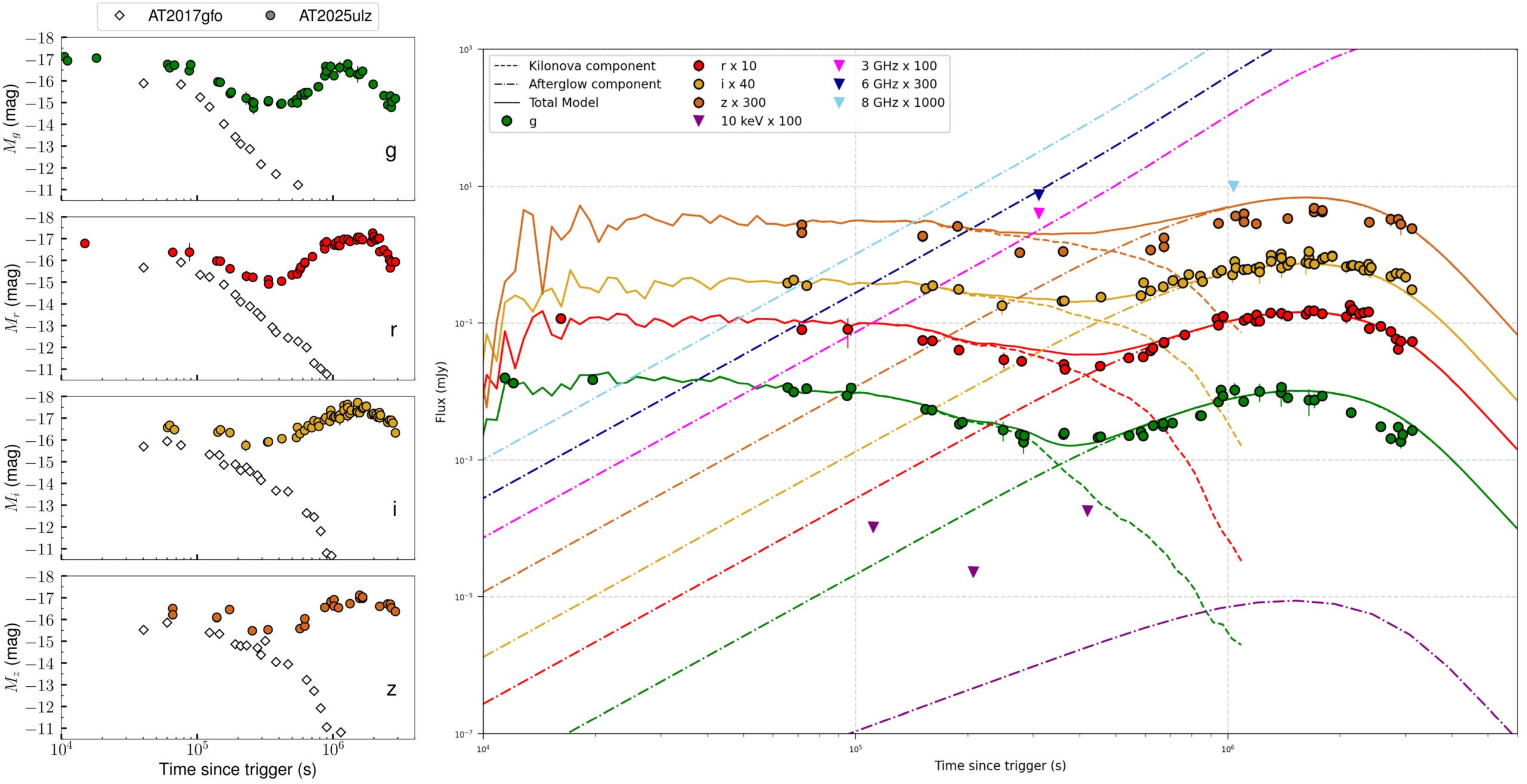

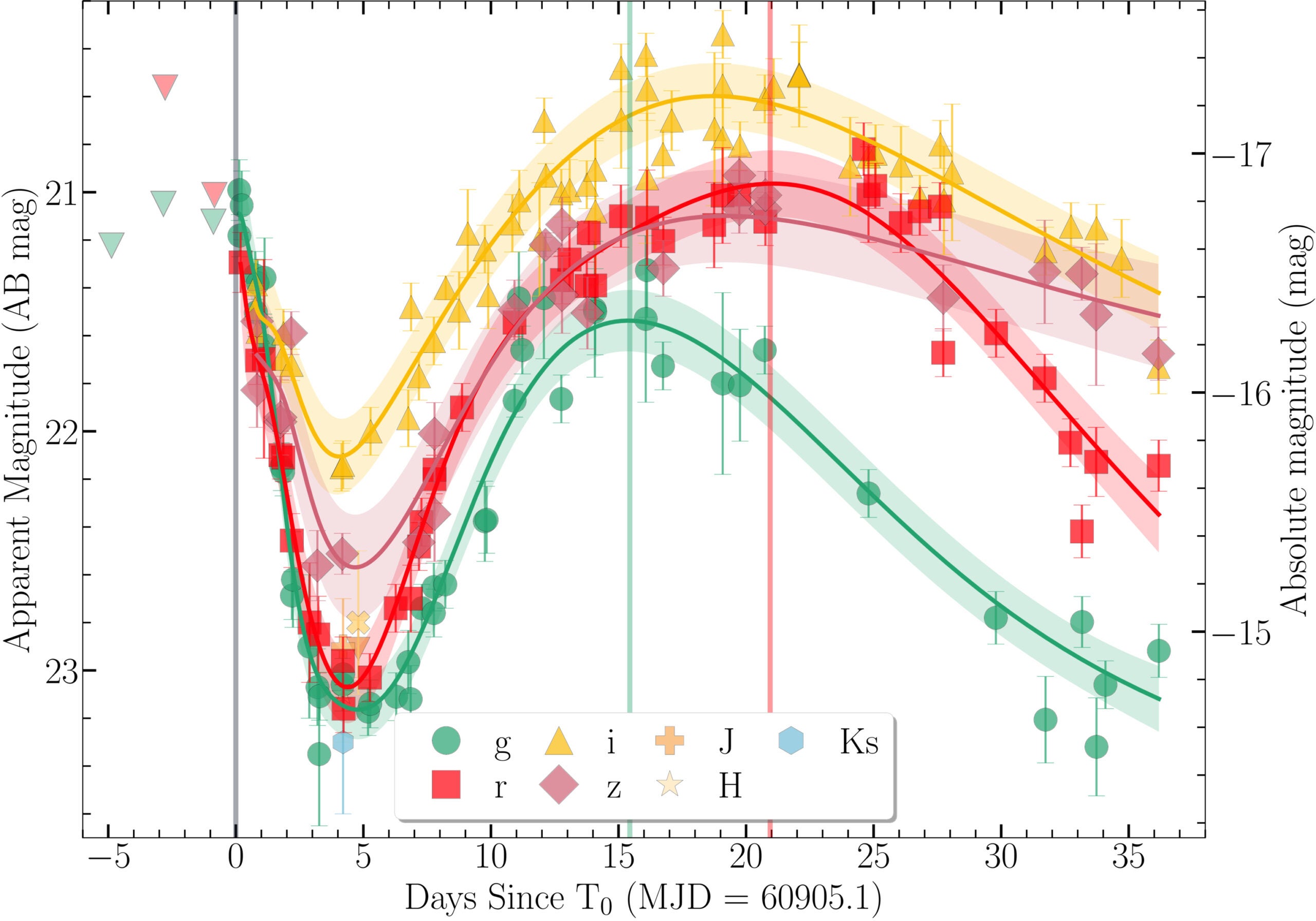

In its earliest phase, AT2025ulz behaved in a way that echoed GW170817. It faded quickly. Its color shifted toward redder wavelengths. Its earliest spectra looked close to featureless, which is common when hot ejecta expand and cool rapidly.

Kasliwal described the emotional whiplash of those first days. “At first, for about three days, the eruption looked just like the first kilonova in 2017,” says Caltech’s Mansi Kasliwal (PhD ’11), professor of astronomy and director of Caltech’s Palomar Observatory near San Diego. “Everybody was intensely trying to observe and analyze it, but then it started to look more like a supernova, and some astronomers lost interest. Not us.”

Modeling supported the initial kilonova-like impression. Fits to the first 2.5 to 3 days of ZTF data favored two ejecta components: a fast “dynamical” outflow of about 0.02 solar masses and a slower disk wind around 0.09 solar masses. The early peak reached an absolute magnitude near −17, about 0.5 to 1 magnitude brighter than GW170817’s kilonova.

Then the story broke from the expected script. Instead of fading away, the light curve flattened and brightened again, forming a second peak in multiple filters. A combined “kilonova plus off-axis afterglow” model could reproduce the optical shape, but it predicted radio and X-ray emission that should have been detectable. Follow-up observations found only upper limits. The color evolution also resisted a clean afterglow explanation.

About a week in, the spectra began to resemble a stripped-envelope core-collapse supernova. A broad P Cygni feature appeared near 6200 angstroms, consistent with fast-moving hydrogen if interpreted as H-alpha. Later spectra showed helium lines, including He I at 5876 angstroms. Comparisons with supernova templates pointed most strongly to a Type IIb supernova, which often shows two peaks: an early one from shock cooling and a later one powered by radioactive nickel-56.

AT2025ulz still looked odd for a typical Type IIb. Its absorption profile around the key feature took on a “W-shaped” form rather than a more common “U shape,” hinting at blended lines or complex geometry. Its colors also deviated from a comparison sample, even after dust corrections and plausible redshift-related adjustments. The study suggests that added opacity from heavy elements mixed into the ejecta could help explain the unusual color evolution.

“We also used radiation-hydrodynamics modeling to estimate the explosion’s physical properties. The best-fitting scenario suggested an extended envelope radius around 140 solar radii, an ejecta mass near 3 solar masses, a thin hydrogen envelope around 0.06 solar masses, and a kinetic energy of about 1.6 foe, or 1.6 × 10^51 ergs. The modeling we used preferred an explosion time about 1.4 days before the nominal gravitational-wave trigger time,” Kasliwal told The Brighter Side of News.

“If that interpretation is right, AT2025ulz could be an ordinary supernova that happened to occur near the gravitational-wave candidate by chance. Rate estimates put that coincidence probability at a few percent, roughly 3 to 5 percent, given the search volume and timing. That is not tiny,” she continued.

But the gravitational-wave mass estimate also refuses to go away. “While not as highly confident as some of our alerts, this quickly got our attention as a potentially very intriguing event candidate,” says David Reitze, the executive director of LIGO and a research professor at Caltech. “We are continuing to analyze the data, and it’s clear that at least one of the colliding objects is less massive than a typical neutron star.”

To reconcile a Type IIb-like supernova with a subsolar-mass merger, the researchers point to a more speculative, but physically motivated, framework: a “superkilonova.” In this picture, a rapidly spinning massive star collapses and launches a supernova. A dense accretion disk forms and becomes unstable. Clumps in the disk could cool and collapse into subsolar-mass neutron stars. Those newborn objects could merge minutes to hours later, producing gravitational waves with a low chirp mass, while the larger stellar explosion dominates the optical display.

Columbia University theorist Brian Metzger, a co-author, outlined why the low masses matter. “The only way theorists have come up with to birth sub-solar neutron stars is during the collapse of a very rapidly spinning star,” Metzger says. “If these ‘forbidden’ stars pair up and merge by emitting gravitational waves, it is possible that such an event would be accompanied by a supernova rather than be seen as a bare kilonova.”

The team does not claim proof. The evidence is a pattern: a low-mass gravitational-wave candidate, a fast red transient that later looks like a Type IIb supernova, and lingering anomalies that could hint at heavy-element mixing. More events, and stronger gravitational-wave confidence, will decide whether this was a real “multimessenger symphony” or a near miss.

If the association holds, the payoff is large. It would expand the catalog of kilonova-like events beyond the clean template of GW170817 and show that some mergers may hide inside supernova light. That would change how you search for these events in wide-field surveys, pushing teams to keep following odd supernovae instead of dropping them as routine.

It would also open a new path for studying how heavy elements form. Kilonovae are key sites for r-process elements like gold and uranium. A superkilonova could mix those products into supernova ejecta in a way that leaves subtle color or spectral fingerprints. If future events confirm that signature, you would gain a new tool for tracing heavy-element production across cosmic history.

Finally, it would challenge models of neutron star formation. Subsolar-mass neutron stars do not fit standard expectations. Confirming them would force theorists to sharpen ideas about rapidly spinning stellar collapse, disk fragmentation, and the extreme physics of dense matter.

Research findings are available online in the journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Cosmic blast looked like a kilonova, then turned into a superkilonova mystery appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.