A device smaller than a grain of dust may help unlock the kind of quantum computers people have only dreamed about. Built on a standard microchip and almost 100 times thinner than a human hair, this new component gives scientists precise control over laser light using a fraction of the power older tools need.

The work comes from a team led by Jake Freedman, an incoming PhD student in the Department of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, professor Matt Eichenfield, the Karl Gustafson Endowed Chair in Quantum Engineering, and collaborators at Sandia National Laboratories, including co-senior author Nils Otterstrom. Together, they designed an optical phase modulator that is not just tiny, but practical to manufacture at scale.

Instead of building a delicate, custom device in a specialized lab, they used the same industrial process that makes chips for laptops, phones, cars and even home appliances. That choice turns an advanced research idea into something that could one day be produced by the millions.

Many of the most promising quantum computers store information in individual atoms or ions held in place by electric or magnetic fields. These trapped atoms act as qubits, the quantum version of bits, and lasers act as the “voices” that give them instructions.

To perform calculations, each qubit must be hit with laser beams tuned to extremely specific colors. The frequency of each laser needs to be set with astonishing precision, often to within billionths of a percent. If the color is off even slightly, the qubit may receive the wrong instruction or no instruction at all.

“Creating new copies of a laser with very exact differences in frequency is one of the most important tools for working with atom- and ion-based quantum computers,” Freedman said. “But to do that at scale, you need technology that can efficiently generate those new frequencies.”

Right now, most labs use bulky table-top devices to shift laser frequencies. These setups work for small experiments, but they use a lot of microwave power and take up a lot of space. They cannot be multiplied into the tens or hundreds of thousands of channels needed for truly large quantum machines.

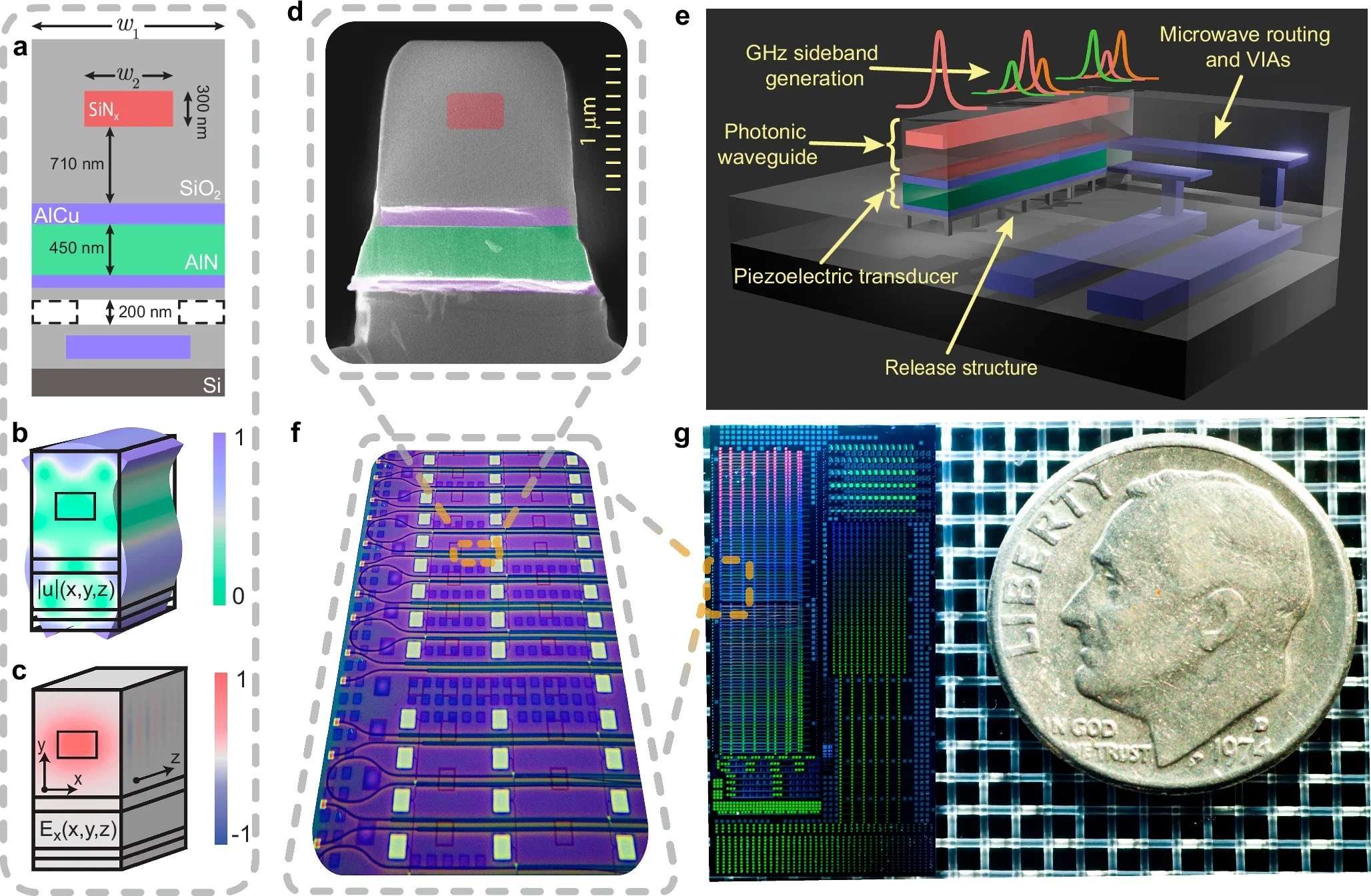

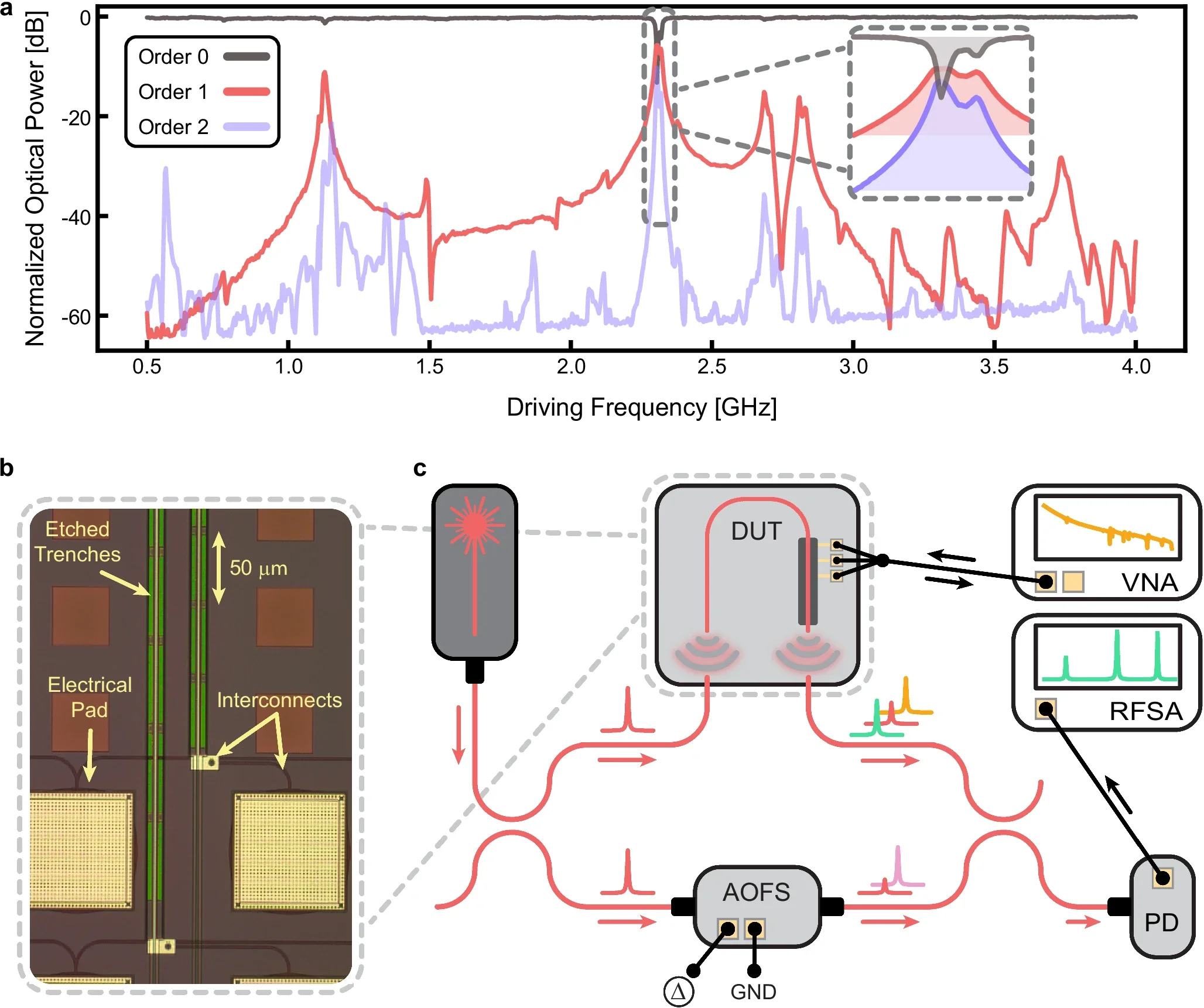

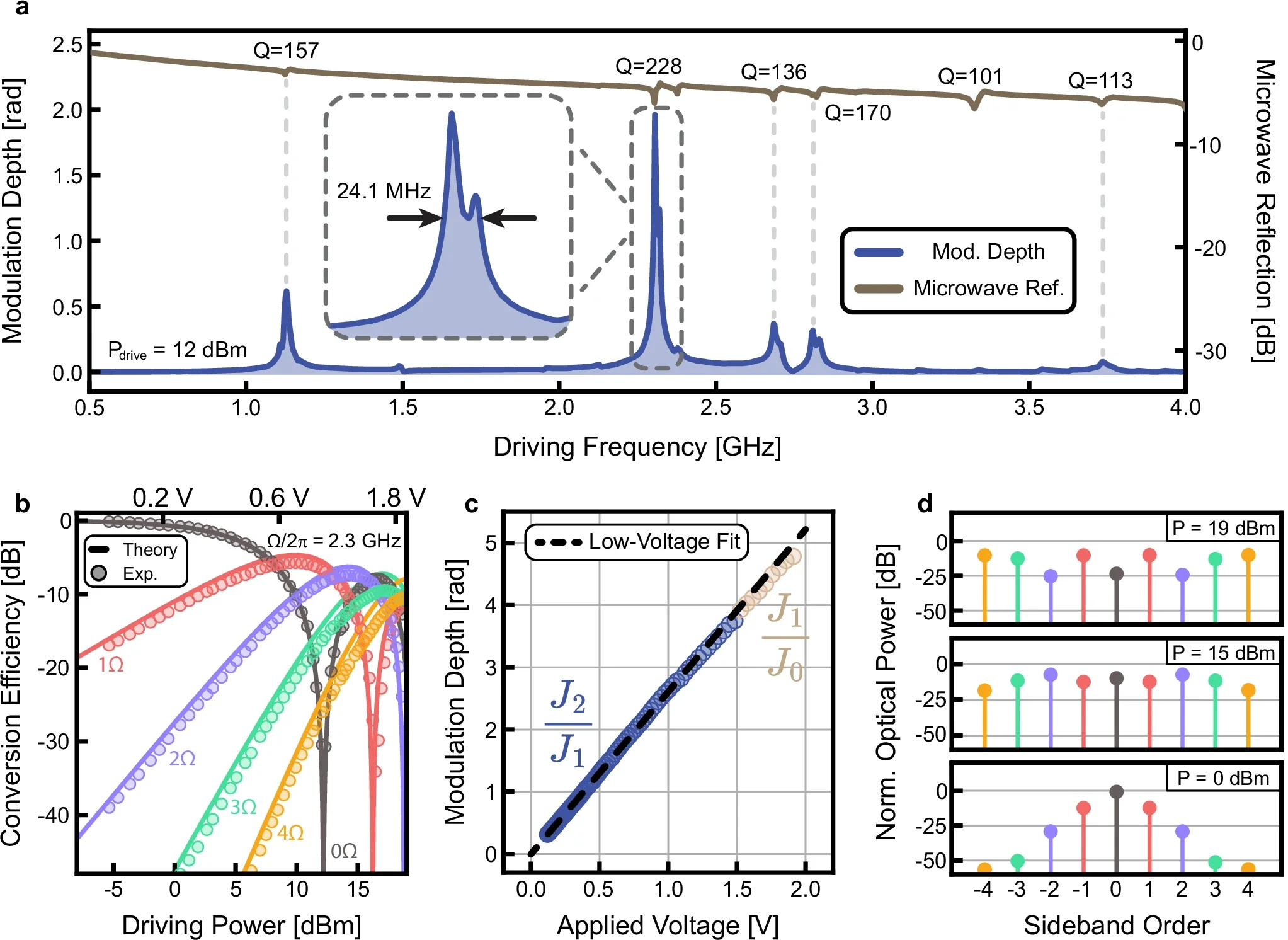

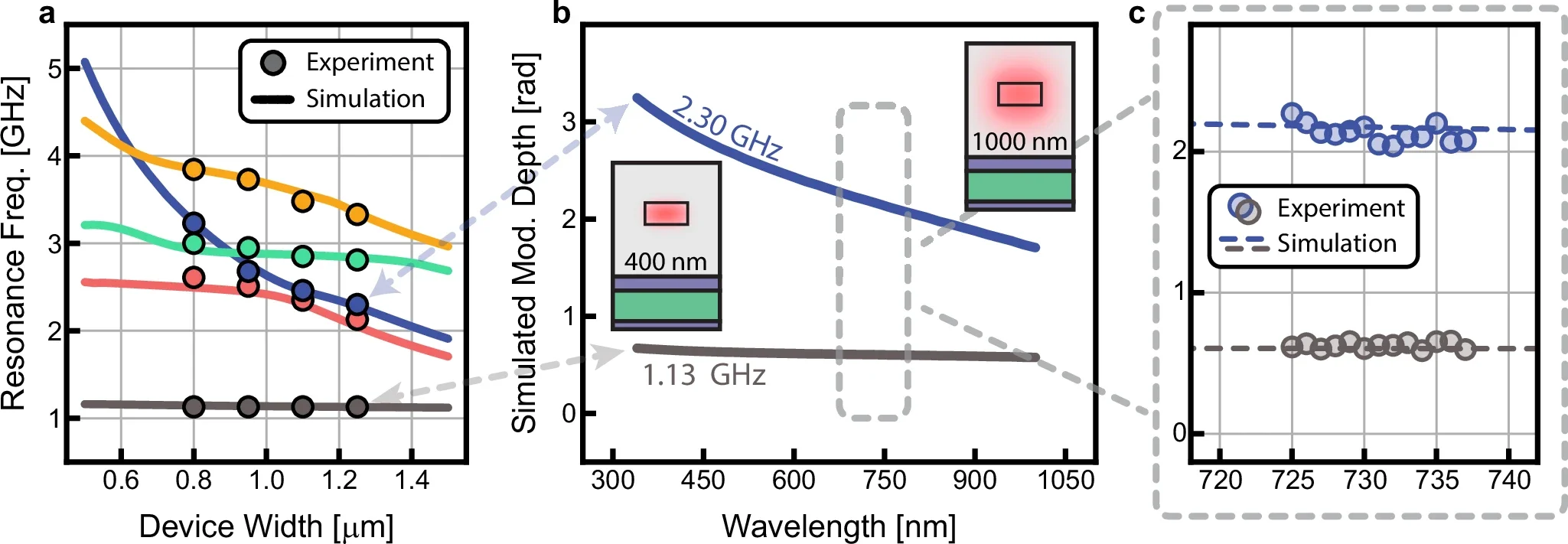

The new chip solves several of those problems at once. It uses microwave-frequency vibrations, oscillating billions of times each second, to sculpt the phase of a laser beam that passes through the device. By shifting the phase, the chip can generate new laser frequencies that are stable, efficient and finely controlled.

In practical terms, that means one strong “master” laser can be split into many slightly different colors, each tuned to control a specific group of qubits. All of that can happen on a cluster of small chips instead of on a warehouse full of optical tables.

The team’s device also uses far less power than many commercial phase modulators. According to the researchers, it consumes roughly 80 times less microwave power than common bulk systems when generating new frequencies of light. Less power means less heat. Less heat lets you pack many more channels tightly together, which is crucial if you want thousands of optical control lines on a single module.

“You’re not going to build a quantum computer with 100,000 bulk electro-optic modulators sitting in a warehouse full of optical tables,” Eichenfield said. “You need some much more scalable ways to manufacture them that don’t have to be hand-assembled and with long optical paths. While you’re at it, if you can make them all fit on a few small microchips and produce 100 times less heat, you’re much more likely to make it work.”

One of the most powerful choices the team made was to use CMOS fabrication, the standard process used to make modern logic chips. Instead of relying on one-off custom parts, they designed the device so it could be etched and built in a commercial foundry.

“CMOS fabrication is the most scalable technology humans have ever invented,” Eichenfield said. “Every microelectronic chip in every cell phone or computer has billions of essentially identical transistors on it. So, by using CMOS fabrication, in the future, we can produce thousands or even millions of identical versions of our photonic devices, which is exactly what quantum computing will need.”

By staying inside that ecosystem, their phase modulators can ride the same manufacturing wave that brought the cost of transistors down over decades. Otterstrom noted that this marks a shift for light-based hardware.

“We’re helping to push optics into its own ‘transistor revolution,’ moving away from the optical equivalent of vacuum tubes and towards scalable integrated photonic technologies,” he said.

The chip’s core trick is to merge tiny mechanical vibrations with guided laser light on the same piece of silicon. When microwave signals drive the structure, it vibrates at very high frequencies and nudges the passing light in a controlled way. That motion carves the laser into a set of new, sharply defined frequencies, all on a footprint small enough to tile across a chip.

“Because the device is compact, efficient and built with mainstream tools, it is more than a one-off demonstration. It looks like a building block. Our team is already working on fully integrated photonic circuits that combine several functions on the same chip, including generating new frequencies, filtering them and shaping light pulses,” Eichenfield shared with The Brighter Side of News.

‘Our goal is not just a single clever device, but a complete optical control system on a handful of chips. Those chips could plug into the front end of a trapped-ion or trapped-atom quantum computer and handle thousands of precision laser channels without sprawling hardware,” he continued.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to partner with quantum computing companies to test these phase modulators inside working machines. They want to see how the chips behave when connected directly to real qubits, not just test lasers in the lab.

“This device is one of the final pieces of the puzzle,” Freedman said. “We’re getting close to a truly scalable photonic platform capable of controlling very large numbers of qubits.”

The project received support from the U.S. Department of Energy through the Quantum Systems Accelerator program, part of the National Quantum Initiative. That backing reflects how central light control has become for the country’s quantum technology roadmap.

This work points toward quantum computers that can grow from dozens of qubits to thousands or even millions without hitting a wall of power, size and cost. By moving frequency control from table-top boxes to CMOS chips, the technology gives quantum engineers a realistic path to scaling the number of optical channels they can manage.

Lower power use and lower heat can also reduce cooling demands, which is a major cost in many quantum systems. In addition, the same kind of precise light control is useful for quantum sensing and quantum networking, where stable, tunable lasers act as the backbone of measurement and secure communication.

Because the device is built in standard fabs, it can be reproduced at industrial scale. That opens the door to a supply chain for advanced photonic parts similar to what exists for electronic chips today. Over time, that could drive down costs and speed up innovation in fields that depend on clean, controllable laser light, from precision measurement to secure links between future quantum computers.

For humanity, the long term payoff could be new kinds of computation, more sensitive detectors and more secure communication channels, all built on small, efficient pieces of hardware that look more like today’s chips than yesterday’s optical benches.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Device smaller than a grain of dust looks to supercharge quantum computers appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.