Researchers from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Curtin University in Australia are reshaping how you understand the rhythm of Earth’s deep past. Led by geophysicist Ross Mitchell and co-authored by Uwe Kirscher, the team reports evidence that Earth’s day length stopped changing for nearly a billion years. Their findings appear in the journal Nature Geoscience.

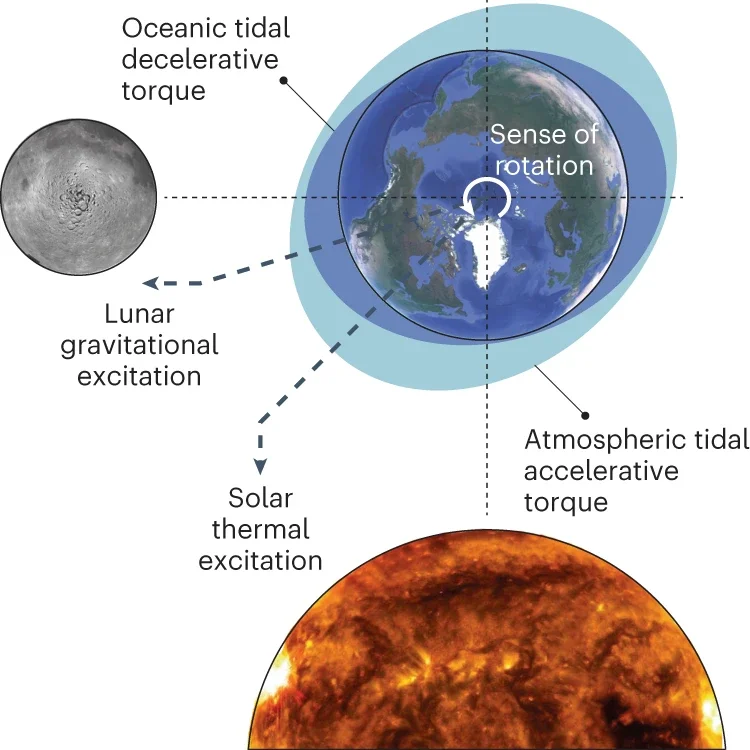

Earth’s rotation has never been fixed. From the planet’s earliest history, tidal forces from the Moon have acted like a slow brake. Because Earth spins faster than the Moon orbits, the ocean’s tidal bulge is pushed slightly ahead of the Moon. That offset pulls on the Moon and transfers angular momentum. The Moon drifts outward, and Earth’s rotation slows. Over time, days grow longer.

For decades, most models suggested this process unfolded smoothly over billions of years. The farther back you go, the thinking went, the shorter the day. But Mitchell and Kirscher found that this simple picture does not match the geological record.

“Over time, the Moon has stolen Earth’s rotational energy to boost it into a higher orbit farther from Earth,” Mitchell said. Even so, the new data show that Earth’s rotation did not always slow at a steady pace.

Earlier hints suggested that Earth’s day might have stalled during the Precambrian. One proposed explanation focused on Earth’s atmosphere. In addition to ocean tides raised by the Moon, sunlight heats the atmosphere and creates solar atmospheric tides. Unlike lunar tides, which slow Earth’s spin, solar tides push in the opposite direction and speed it up.

“Most models of Earth’s rotation predict that day length was consistently shorter and shorter going back in time,” Kirscher said. “But a slow and steady change in day length going back in time is not what we found.”

If lunar and solar tides ever balanced each other, Earth’s rotation could have stabilized. Testing that idea proved difficult. Early estimates of ancient day length came from stromatolite growth patterns or tidal rhythmites. These records are rare and often debated, leaving large gaps in the Precambrian timeline.

The lack of reliable data kept the idea of a stalled day length on the margins for years. That changed with new tools and a surge of high-quality geological records.

The breakthrough came from cyclostratigraphy, a method that reads rhythmic patterns preserved in sedimentary rocks. These patterns reflect Milankovitch cycles, subtle changes in Earth’s orbit and rotation that influence climate. Because the timing of these cycles depends on how fast Earth spins, they provide a natural clock.

“Two Milankovitch cycles, precession and obliquity, are related to the wobble and tilt of Earth’s rotation axis in space,” Kirscher explained. Faster rotation in the past leaves a clear signature in shorter cycles.

Over the past seven years, researchers have produced more than half of all available Precambrian day-length estimates using this approach. Mitchell and Kirscher compiled 12 new constraints, creating the most detailed record yet of early Earth rotation.

“We realized that it was finally time to test a kind of fringe, but completely reasonable, alternative idea about Earth’s paleorotation,” Mitchell said.

The expanded dataset revealed a striking pattern. From roughly two billion to one billion years ago, Earth’s day length appears to have flatlined at about 19 hours. Statistical analysis shows a clear change point in the data, marking a long pause in the gradual lengthening of the day.

This period aligns with what geologists often call the “boring billion,” a stretch marked by slow biological evolution and relative environmental stability. “The billion years,” Mitchell noted, are commonly referred to by that name.

The findings support the idea that Earth entered a tidal resonance. During this time, the slowing effect of lunar ocean tides was balanced by the speeding effect of solar atmospheric tides. When the two forces matched, Earth’s rotation stopped changing.

The resonance appears to have occurred at a 19-hour day, not the 21-hour period assumed in earlier models. That difference suggests Earth’s ancient atmosphere behaved differently than today’s, allowing atmospheric waves to travel faster.

To sustain a 19-hour day, Earth’s atmosphere would have needed to support faster-moving atmospheric tides. The timing overlaps with major changes in atmospheric chemistry, including the Great Oxidation Event.

As oxygen rose, ozone formed. Ozone absorbs sunlight at higher altitudes than water vapor and plays a strong role in driving atmospheric tides. Its presence may have amplified solar tides enough to counter lunar braking.

Later, during a period sometimes called the exit from oxygen, atmospheric oxygen levels fell again. That shift likely warmed the surface and altered atmospheric structure. Warmer temperatures and lower oxygen would have increased wave speeds, keeping Earth close to resonance.

How Earth eventually escaped this balance remains uncertain. Changes in climate or atmospheric composition during the Neoproterozoic, a time of dramatic climate swings, may have tipped the system.

A billion years of stable day length affects more than the clock. If resonance held Earth’s rotation steady, the Earth-Moon system may have gained extra angular momentum. That possibility challenges assumptions used in many rotation models and points to the need for new approaches.

At the surface, the pause in rotational change lines up with long periods of slow tectonic activity. Rotational energy influences stresses in Earth’s crust. Stable rotation could have reduced tectonic turnover, limiting nutrient cycling and slowing biological innovation.

“Short days may also have constrained early life. Photosynthetic organisms need sunlight to produce oxygen. With only 19 hours per day, the window for sustained photosynthesis was limited. Oxygen may have accumulated slowly as a result,” Mitchell shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“Only after Earth escaped resonance and days grew longer could photosynthesis operate long enough to support rising oxygen levels and, eventually, complex life,” he continued.

The idea resonates beyond the study team. Timothy Lyons of the University of California, Riverside, who was not involved in the research, said, “It’s fascinating to think that the evolution of the Earth’s rotation could have affected the evolving composition of the atmosphere.”

The new Precambrian record offers the strongest evidence yet that Earth’s rotation paused for a billion years. It links celestial mechanics, atmospheric chemistry, climate, and biology into a single story.

The close match between geological data and theoretical predictions strengthens the case for tidal resonance. At the same time, the unexpected 19-hour period invites new research into how ancient atmospheres behaved.

More cyclostratigraphic studies will help refine the timeline and clarify how Earth entered and exited this unusual state. What emerges is a reminder that even something as familiar as the length of a day has shaped the planet’s history in profound ways.

It is hard enough to finish everything in a modern 24-hour day. Life on early Earth faced that challenge with far less time.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Earth’s day was only 19 hours long for a billion years, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.