Earth’s deep interior still shapes the world above your feet. Water trapped far below the surface helps control how rocks move, melt, and recycle through the mantle. Some of that water carries a chemical signal from Earth’s earliest days, suggesting it arrived during the planet’s violent formation. What remained unclear was how much of this early water became locked inside the mantle as Earth cooled from a global magma ocean.

New research offers a clearer answer. A study led by Prof. DU Zhixue at the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences shows that far more water may have been stored deep inside Earth than scientists once believed. The findings, published in Science, focus on bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral in the lower mantle.

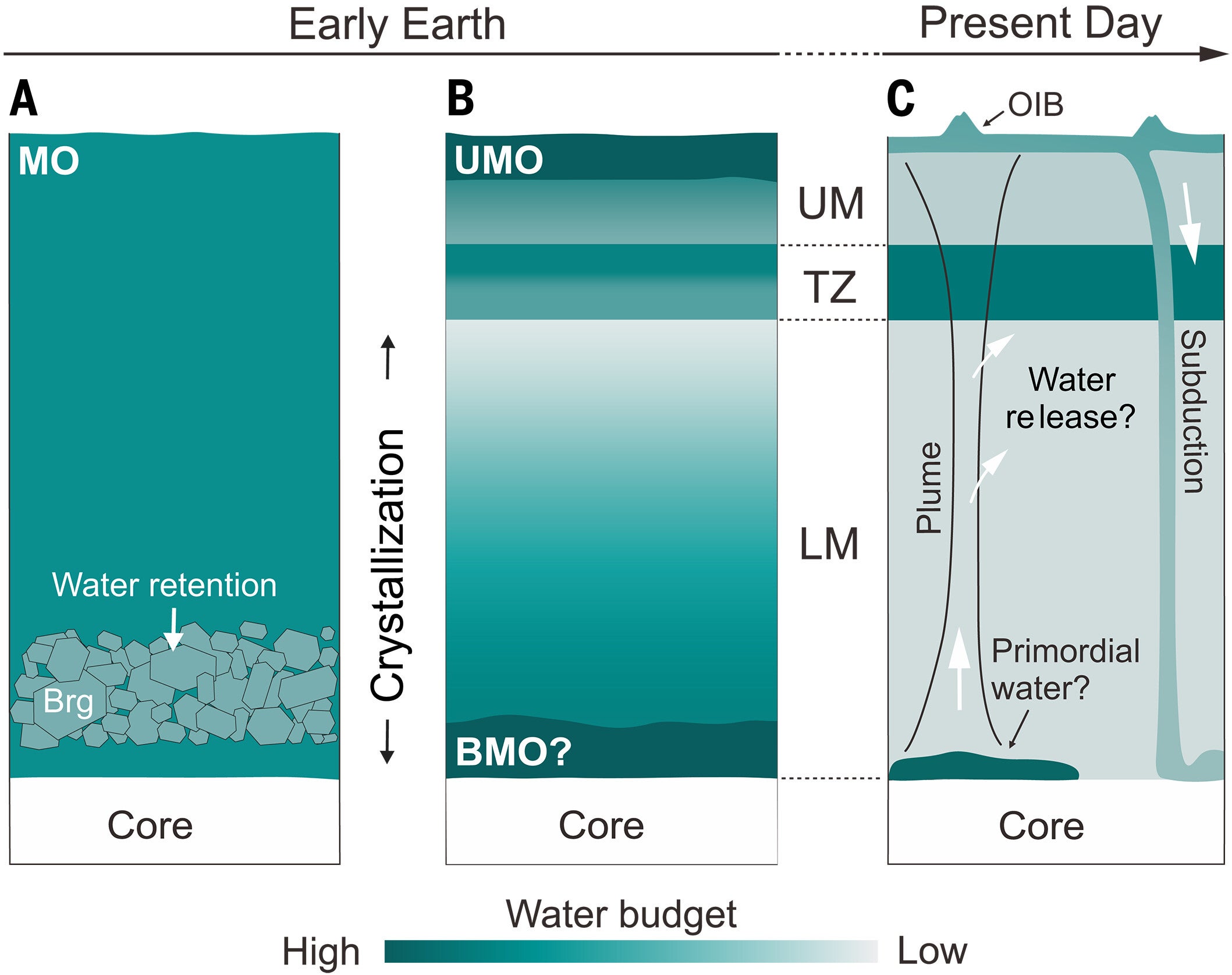

During Earth’s early history, giant impacts likely melted much of the planet, creating deep oceans of magma that reached toward the core–mantle boundary. As these magma oceans cooled, minerals crystallized. Bridgmanite formed early and now makes up nearly 80 percent of the lower mantle. Understanding how water divided between this mineral and molten rock during cooling is key to understanding how Earth retained its earliest water.

Previous experiments suggested bridgmanite could hold only small amounts of water. Many of those studies used lower temperatures and indirect methods. As a result, estimates of water storage varied widely. The new study set out to recreate the extreme conditions of the deep mantle and directly measure how much water bridgmanite can contain.

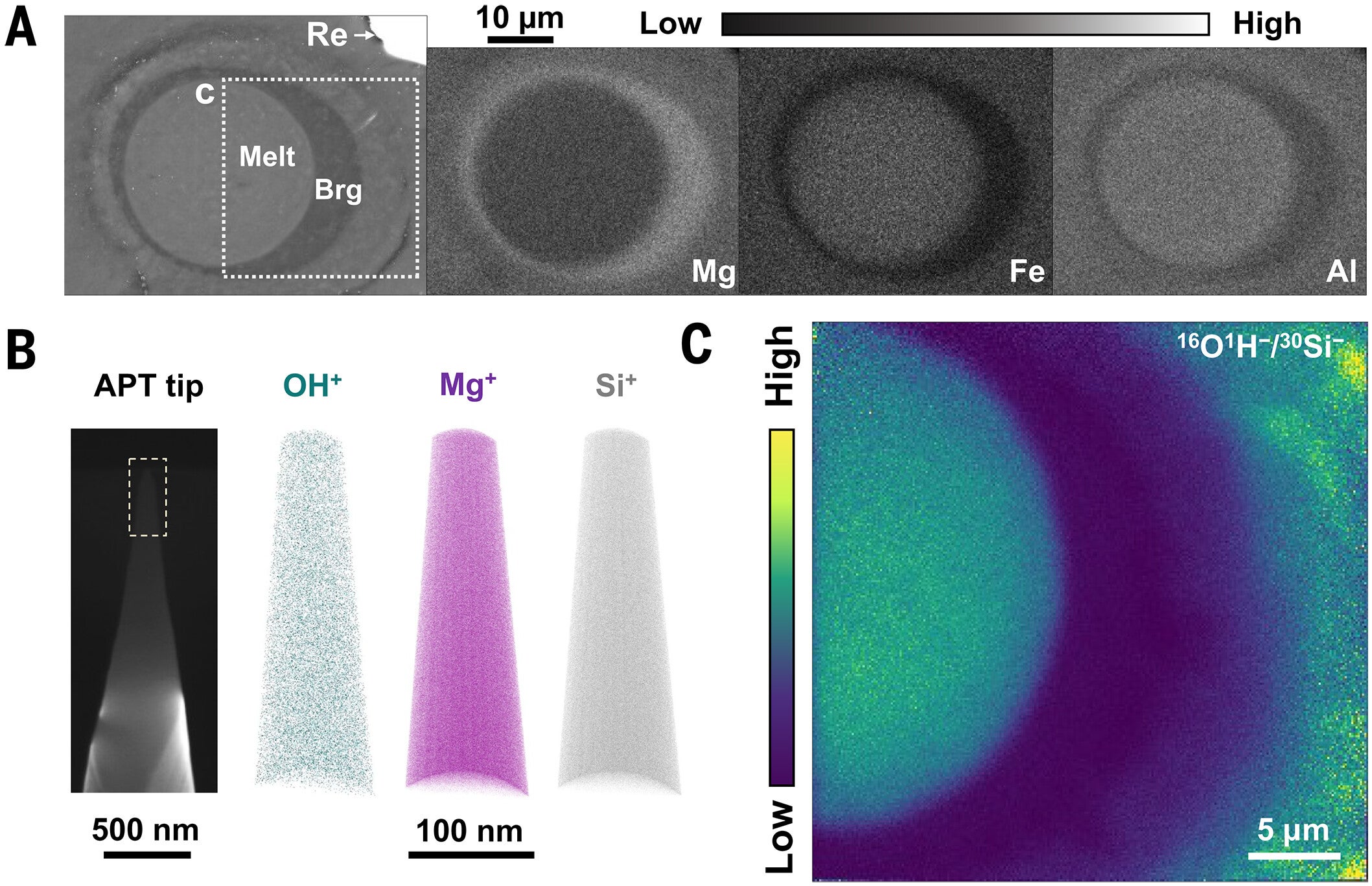

To reach the pressures and temperatures found hundreds of kilometers below the surface, the team used laser-heated diamond anvil cells. These devices squeezed synthetic hydrous silicate glass to pressures between 36 and 71 gigapascals. Temperatures reached roughly 3,600 to 4,400 kelvin, similar to conditions in a deep magma ocean.

The heated region was only tens of micrometers wide, smaller than a grain of sand. Even so, the researchers carefully tracked temperature changes, keeping variations under control. Once heated, the samples cooled and solidified, leaving bridgmanite crystals surrounded by frozen melt.

Chemical tests showed the crystals formed an aluminum-bearing type of bridgmanite, similar to what scientists expect inside Earth. The experiments stayed closed, meaning no water escaped or entered during heating. This ensured the measurements reflected real partitioning between crystal and melt.

To measure water, the team turned to nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry, or NanoSIMS. This method can detect hydrogen at extremely small scales. In collaboration with Prof. LONG Tao from the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, the researchers also used atom probe tomography and advanced diffraction tools. These methods confirmed that water was built into the crystal structure of bridgmanite, not trapped in cracks or defects.

The measurements revealed a clear pattern. Molten rock held much more water than surrounding crystals. Yet bridgmanite still stored more water than earlier work suggested. Depending on starting conditions, bridgmanite contained hundreds to nearly two thousand parts per million of water by weight. The melt contained far more.

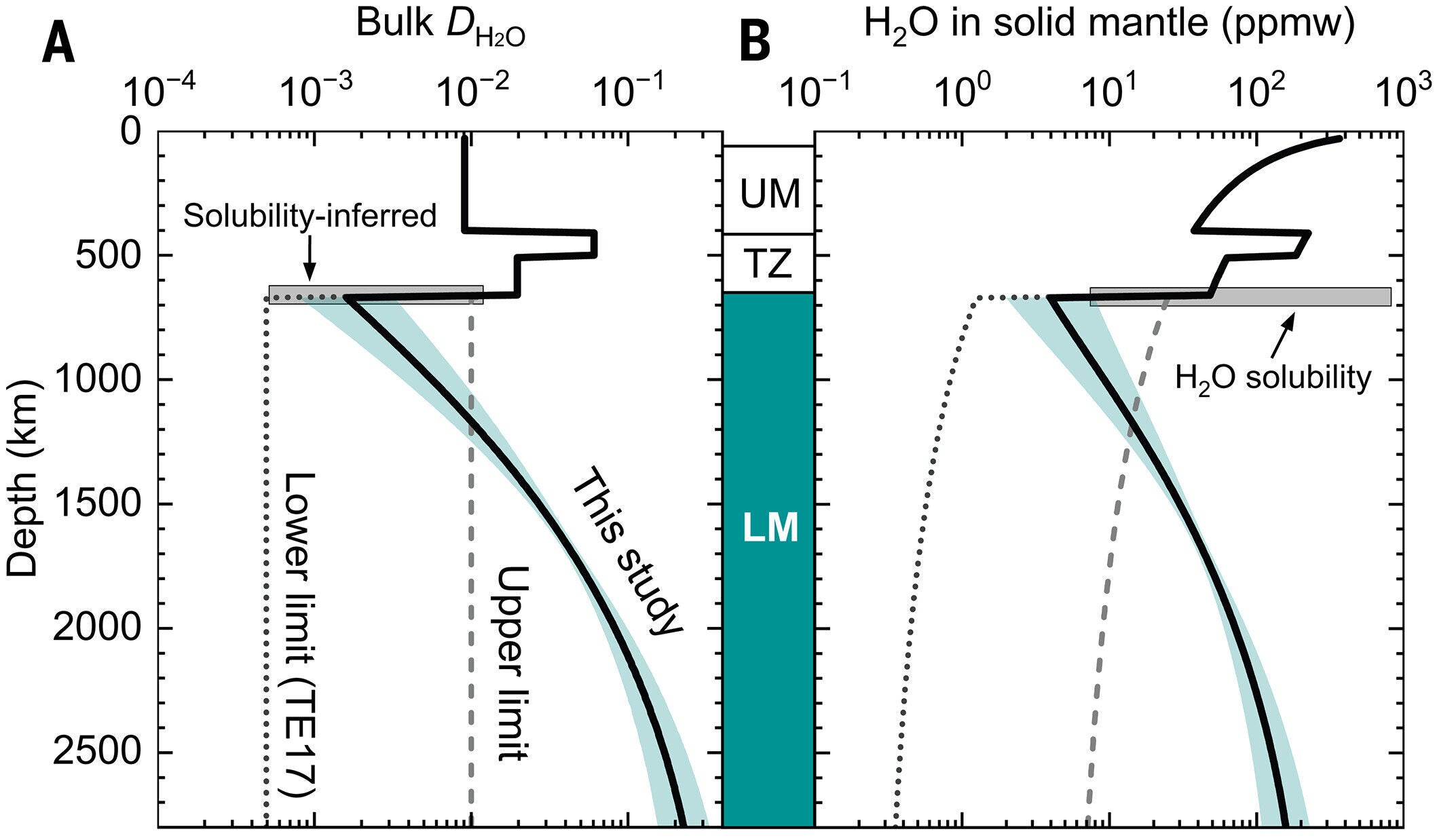

From these values, the team calculated the water partition coefficient. This number describes how water divides between solid and liquid during crystallization. The coefficients ranged from about 0.024 to 0.087 and stayed consistent across a wide range of water contents. That consistency showed the samples reached chemical balance.

When the researchers examined what controlled these values, temperature stood out. Pressure and composition played little role. As temperatures dropped, bridgmanite became more willing to take in water. This strong temperature link matters because Earth’s magma ocean cooled slowly over time.

During the hottest stages, newly formed bridgmanite could lock away significant water. As cooling continued, later crystals trapped even more. This behavior challenges the long-held view that the deep lower mantle is nearly dry.

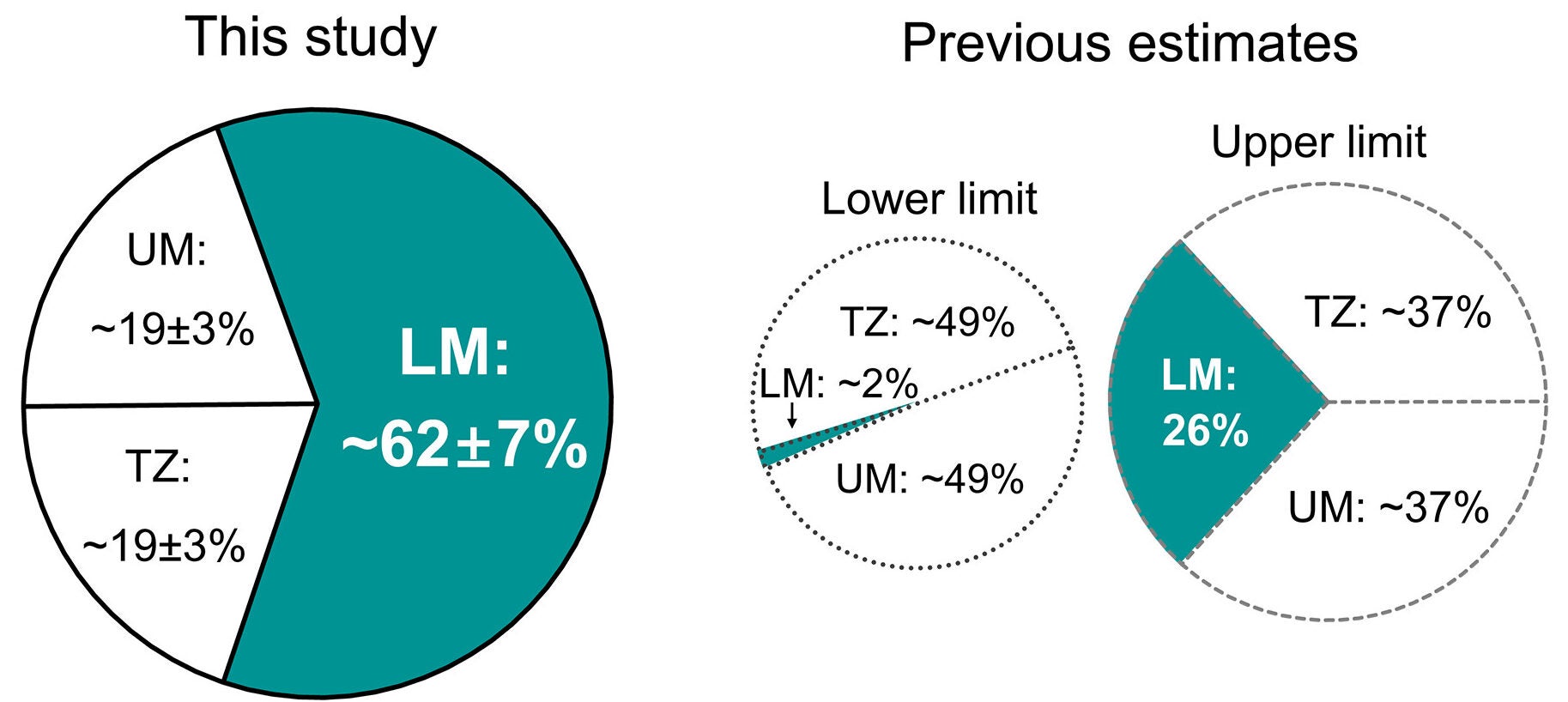

To see what these findings mean for early Earth, the team built models of magma ocean crystallization. The models assumed a fully mixed magma ocean that did not exchange water with the core or atmosphere. Starting water contents ranged from about 0.03 to 0.4 percent by weight, equal to one to twelve modern oceans.

In a bottom-up scenario, crystallization began deep in the mantle and moved upward. As temperatures fell from about 5,300 to 2,600 kelvin, the bulk ability of the mantle to store water changed dramatically. The lower mantle ended up holding far more water than earlier models predicted.

Because the new partition values are higher, the models showed the lower mantle storing five to one hundred times more water than past estimates. Near the top of the magma ocean, leftover melt may have held up to 92 percent of the remaining water. That shallow water could later feed Earth’s early oceans.

The team also tested a case where crystallization began at middle depths, creating both an upper and a basal magma ocean. Even then, the lower mantle remained the largest water reservoir, with an added pocket of water-rich melt near the core–mantle boundary.

“After crystallization, the water budget likely changed as dense, water-rich layers sank and released water at boundaries deeper in the mantle. This process could have helped produce the modern pattern we see today, where the upper mantle tends to be dry while the transition zone holds more water,” Prof. DU Zhixue shared with The Brighter Side of News.

The researchers note that these numbers may still be conservative. If even a small amount of hydrous melt became trapped between crystals, total water storage would rise further. The solid mantle could have retained at least 0.08 to one ocean mass of water, matching modern estimates.

Over time, dense, water-rich layers likely sank and released water at deep boundaries. This process may help explain why today’s upper mantle appears relatively dry while the transition zone holds more water. As mantle convection continued, water slowly moved upward through melting and volcanism.

Cooling of up to 1,000 kelvin since Earth’s formation may have made water less compatible with solid minerals. This change could drive partial melting in the deep mantle, offering clues to unusual seismic signals seen today.

Taken together, the work paints a picture of a planet that preserved much of its early water deep inside. That hidden reserve likely shaped mantle flow, plate motion, and surface conditions over billions of years.

These findings reshape how scientists think about Earth’s habitability. If large amounts of water were stored deep early on, Earth had a built-in reserve that could slowly resupply the surface. This process may have stabilized oceans and climate over geologic time.

The work also helps explain modern mantle behavior, including melting, viscosity changes, and seismic anomalies. Beyond Earth, the results offer clues for understanding water retention on rocky exoplanets during their own magma ocean phases.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Earth’s lower mantle trapped far more early water than previously thought appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.