In an effort to bring together the domains of gravity and quantum theory, Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen proposed a striking concept in a 1935 paper. In that work, they described an abstract mathematical structure they referred to as a “bridge” between two perfectly symmetrical regions of spacetime. Their goal was not to create a mechanism for traveling long distances in space, but rather to analyze the coexistence of matter, gravitational forces, and the extreme gravitational environments associated with such conditions.

Since then, the original Einstein–Rosen bridge idea has been reinterpreted by others and transformed into what is now popularly known as a “wormhole.” Wormholes have become a familiar concept in popular culture and speculative physics. However, Einstein and Rosen never intended to suggest that these bridges could be used for travel between distant regions of space.

New research published in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity shows that the commonly accepted interpretation of the bridge structure is, in fact, incorrect. In this study, the authors take a different approach to analyzing Einstein–Rosen bridges than previous researchers. Their work builds on earlier research conducted by Sravan Kumar and João Marto.

The perception of wormholes continued to grow from the original idea proposed by Einstein and Rosen through the late 1980s. During that period, physicists explored whether two regions of the universe could be connected through extreme gravitational attractors, such as black holes. These studies ultimately concluded that such bridges could not be crossed. Within the framework of general relativity, the connections close too quickly for even light to pass through them.

“As a result, Einstein–Rosen bridges cannot be realized as physical entities. They cannot be maintained or observed and exist only as theoretical constructs. Despite this, the wormhole concept has persisted, largely through works of fiction and theoretical extrapolation, in the absence of experimental evidence for large, traversable wormholes in the universe,” Marto told The Brighter Side of News.

“Our current work revisits the original premise by focusing on Einstein and Rosen’s initial motivation: understanding the relationship between quantum fields and curved spacetime, rather than interstellar travel. Viewed through this lens, the bridge can be reexamined using modern quantum theory,” he continued.

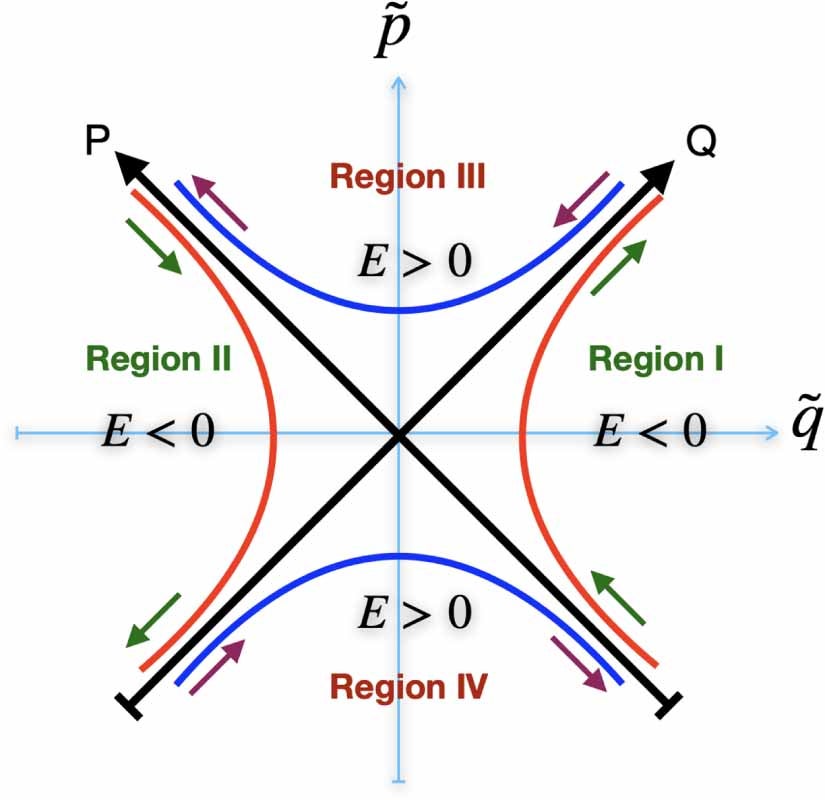

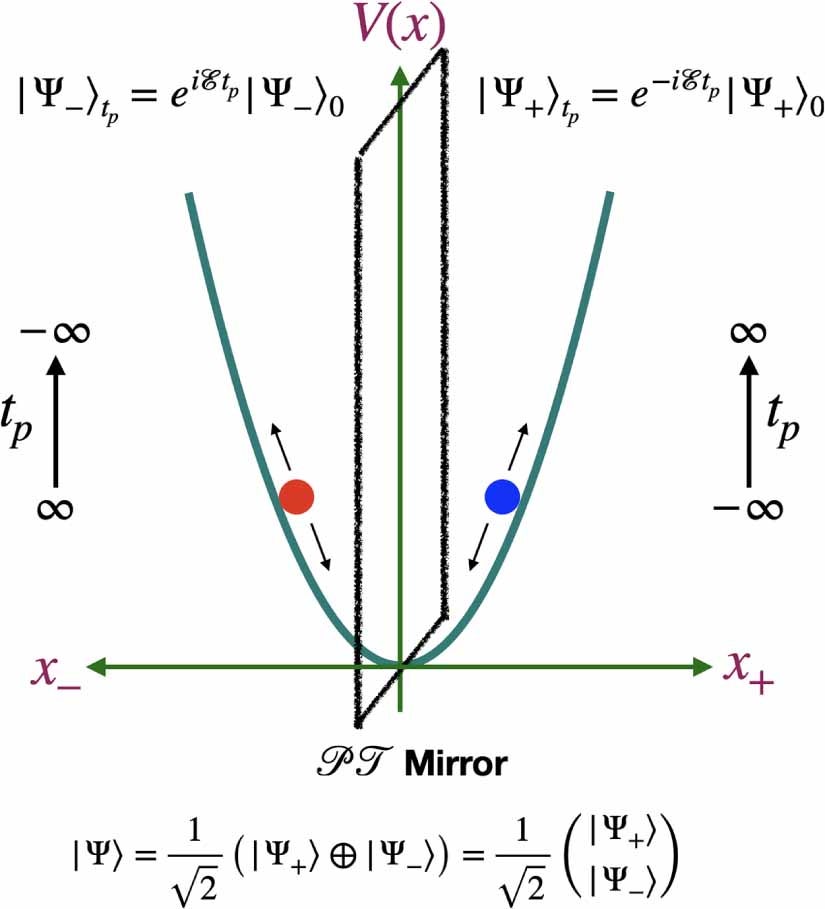

Most fundamental laws of physics treat time as directionless. If the equations describing a physical system are run forward or backward, they yield the same results. The researchers apply this symmetry to the interaction of quantum fields with curved spacetime, which forms the core of their argument.

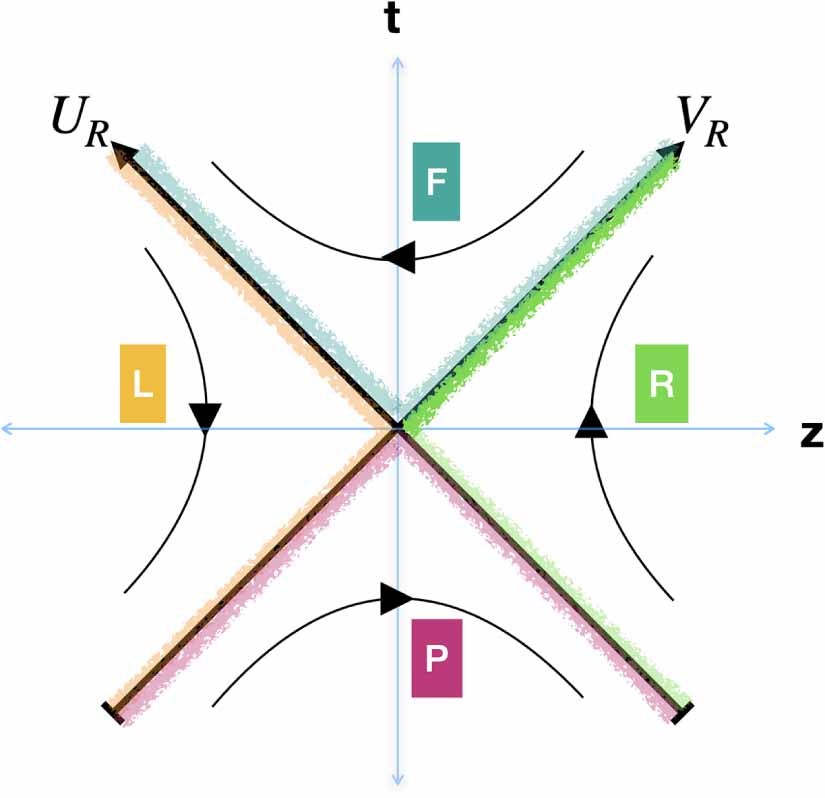

Their model proposes that a quantum system consists of two interdependent components. In one component, time flows forward, as it does from our perspective. In the other, time flows in the opposite direction. Taken together, these components provide a complete quantum description of the system and allow for fully reversible quantum dynamics.

This model challenges the long-standing assumption that there is only a single, universal arrow of time. That assumption works well in flat spacetime, but it breaks down in extreme environments such as black holes or during periods of cosmic expansion and collapse.

By incorporating both the forward-flowing and backward-flowing components of time, the Einstein–Rosen bridge emerges as a natural extension of known physical laws. In this view, the bridge does not function as a passage through space. Instead, it acts as a fundamental link between two mirrored components of a quantum system, much like a mathematical relationship connects different numerical values.

This reinterpretation of black holes also offers a new perspective on one of physics’ most persistent problems: the black hole information paradox. In 1974, Stephen Hawking showed that black holes emit radiation and eventually evaporate. This process appeared to destroy information about everything that fell into the black hole, violating a core principle of quantum mechanics.

According to the authors, the paradox arises from considering only one direction of time when describing black holes. In their framework, information is not destroyed. Instead, it evolves along the backward-flowing time component and is preserved through the bridge.

Although black holes appear to us as regions beyond an event horizon, the authors argue that each black hole remains part of a larger, continuous, and unitary system. This system preserves causality and information without requiring exotic matter or new physical laws.

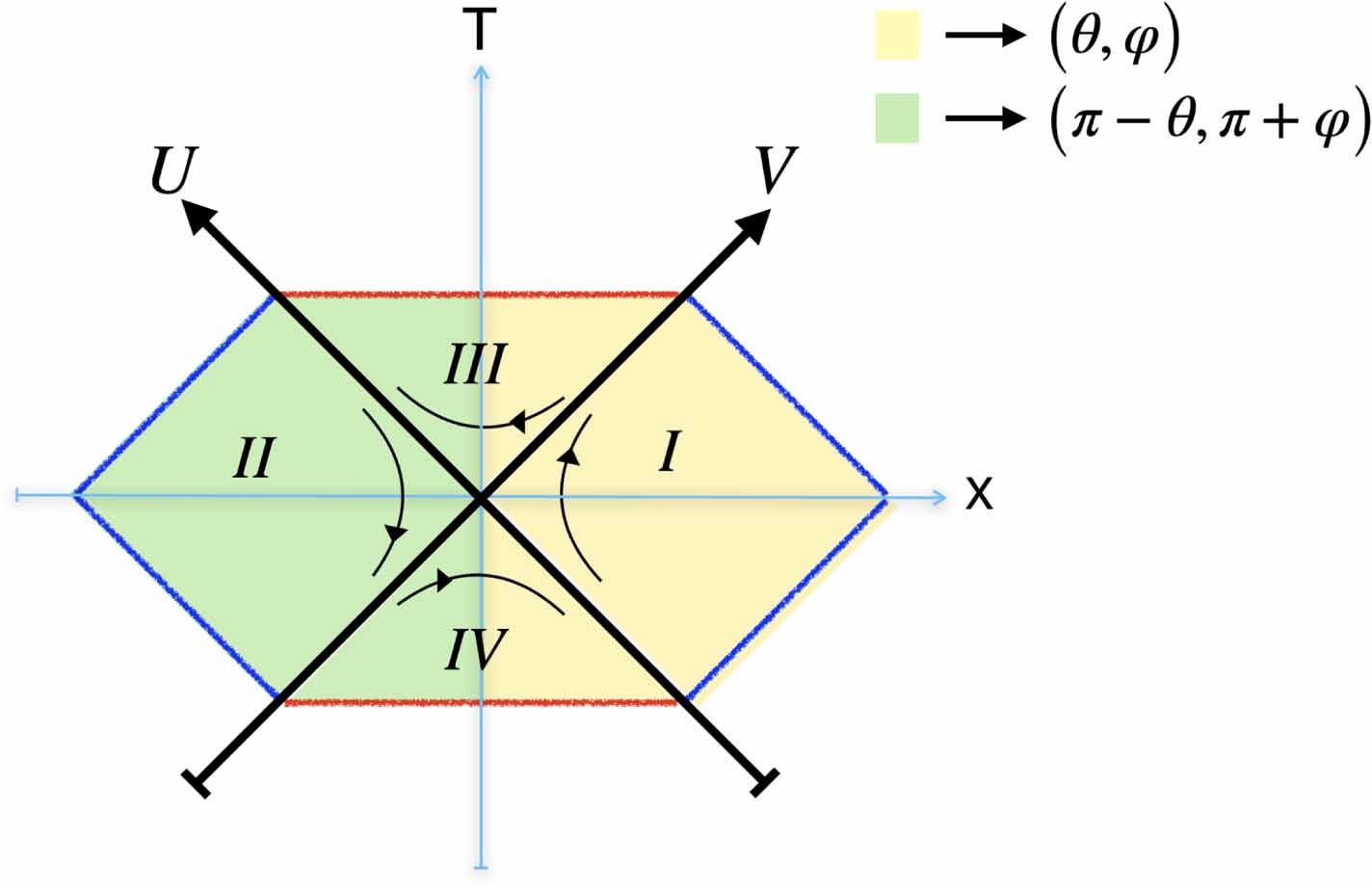

The theory also has implications for cosmological observations. Measurements of the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, reveal subtle but persistent asymmetries. Large-scale patterns show a slight directional preference over their mirrored counterparts.

Standard cosmological models predict such asymmetries only with very low probability. By contrast, models involving mirrored quantum components naturally produce parity asymmetry. When the authors compared their model’s predictions with observational data, they found a significantly better statistical fit.

This does not prove that the model is correct. However, it suggests that the quantum mechanical treatment of time may leave observable signatures in the universe.

The model further suggests that if time fundamentally has two opposing directions, then the Big Bang may not represent an absolute beginning. Instead, it could mark a “quantum bounce” between two time-reversed phases of the universe.

In this scenario, a universe undergoing collapse reaches an extreme state and then rebounds into the expanding universe we observe today. The authors propose that black holes may act as bridges between these two phases, allowing interaction rather than separation into different regions of space.

They further suggest that remnants from this pre-bounce phase, such as small black holes, could still exist today and may contribute to what we identify as dark matter.

If supported by future evidence, this work could reshape how scientists approach the unification of quantum mechanics and general relativity. The framework restores information preservation in curved spacetime and allows black holes to be studied without relying on speculative physics.

The authors believe their findings will guide future observational efforts. New measurements of the cosmic microwave background, gravitational waves, and black hole behavior could test predictions related to the two-sided nature of time. A deeper understanding of time in quantum mechanics would also influence fields such as cosmology and particle physics.

From a human perspective, the greatest value of this research lies in its potential to clarify the origins and ultimate fate of the universe. While it does not promise time machines or faster-than-light travel, it offers a more coherent and internally consistent picture of reality at its most fundamental level.

Research findings are available online in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Einstein–Rosen bridges are not wormholes but quantum links between opposite directions of time appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.