Kidney aging rarely draws attention until something goes wrong. Over time, these organs quietly lose strength, filter less efficiently, and struggle to keep the body balanced. A new study now brings kidney aging into sharp focus by turning to an unlikely helper; a tiny fish that lives its entire life in just a few months.

Scientists reveal how the African turquoise killifish mirrors the aging process of human kidneys at remarkable speed. The work also uncovers how a widely prescribed drug can protect aging kidneys by preserving their delicate blood vessels and cellular health. Together, these findings may reshape how kidney aging is studied and treated.

Kidneys play a constant, demanding role in daily life. They clean waste from the blood, control fluid levels, and help regulate blood pressure. As you age, these tasks become harder. Tiny blood vessels inside the kidneys slowly disappear, a process known as vascular rarefaction. This loss weakens filtration and raises the risk of chronic kidney disease.

Studying this slow decline has long frustrated researchers. In humans, kidney aging unfolds over decades. Even in laboratory mice, it can take years. That long timeline makes experiments costly and limits how many potential treatments can be tested.

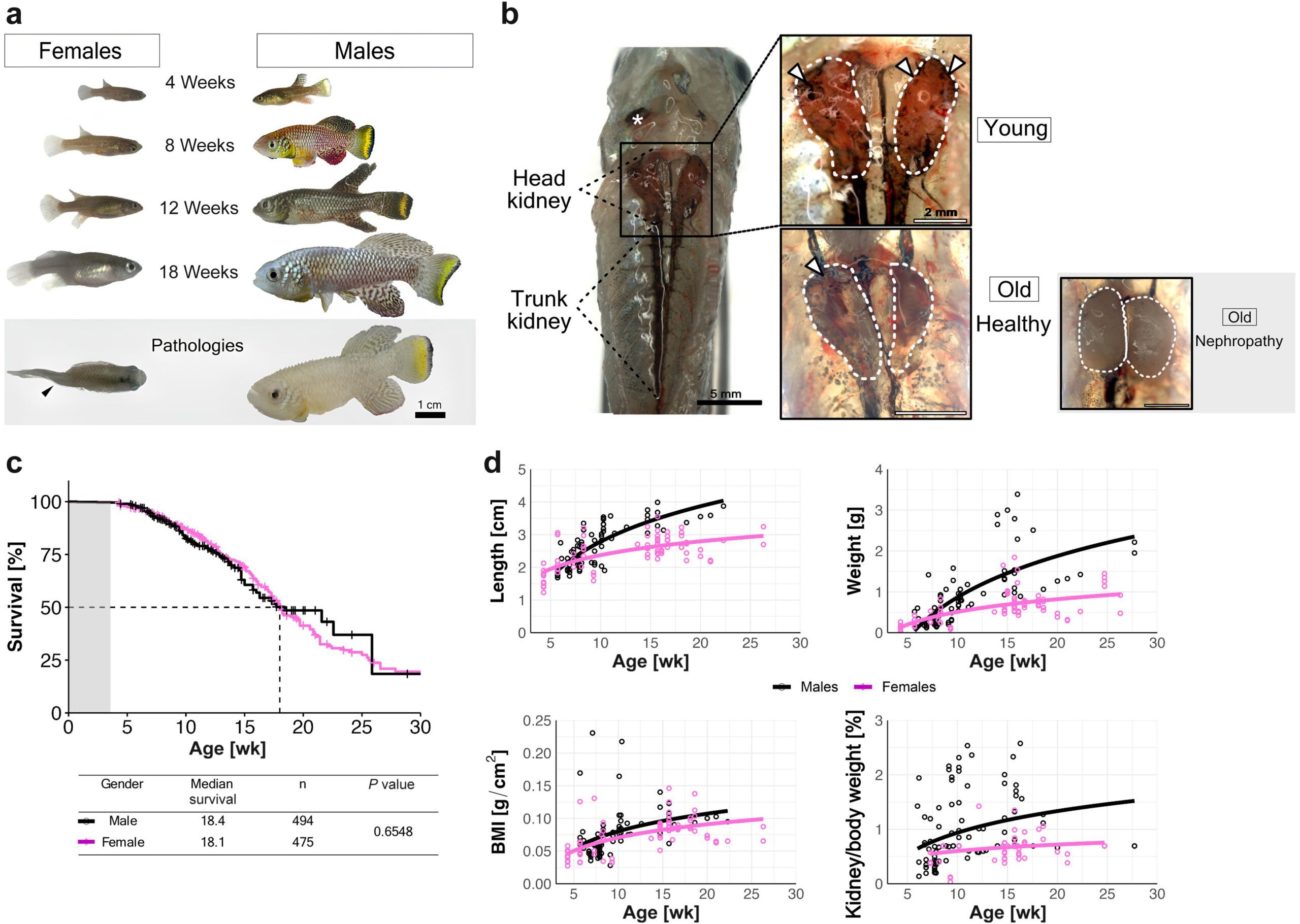

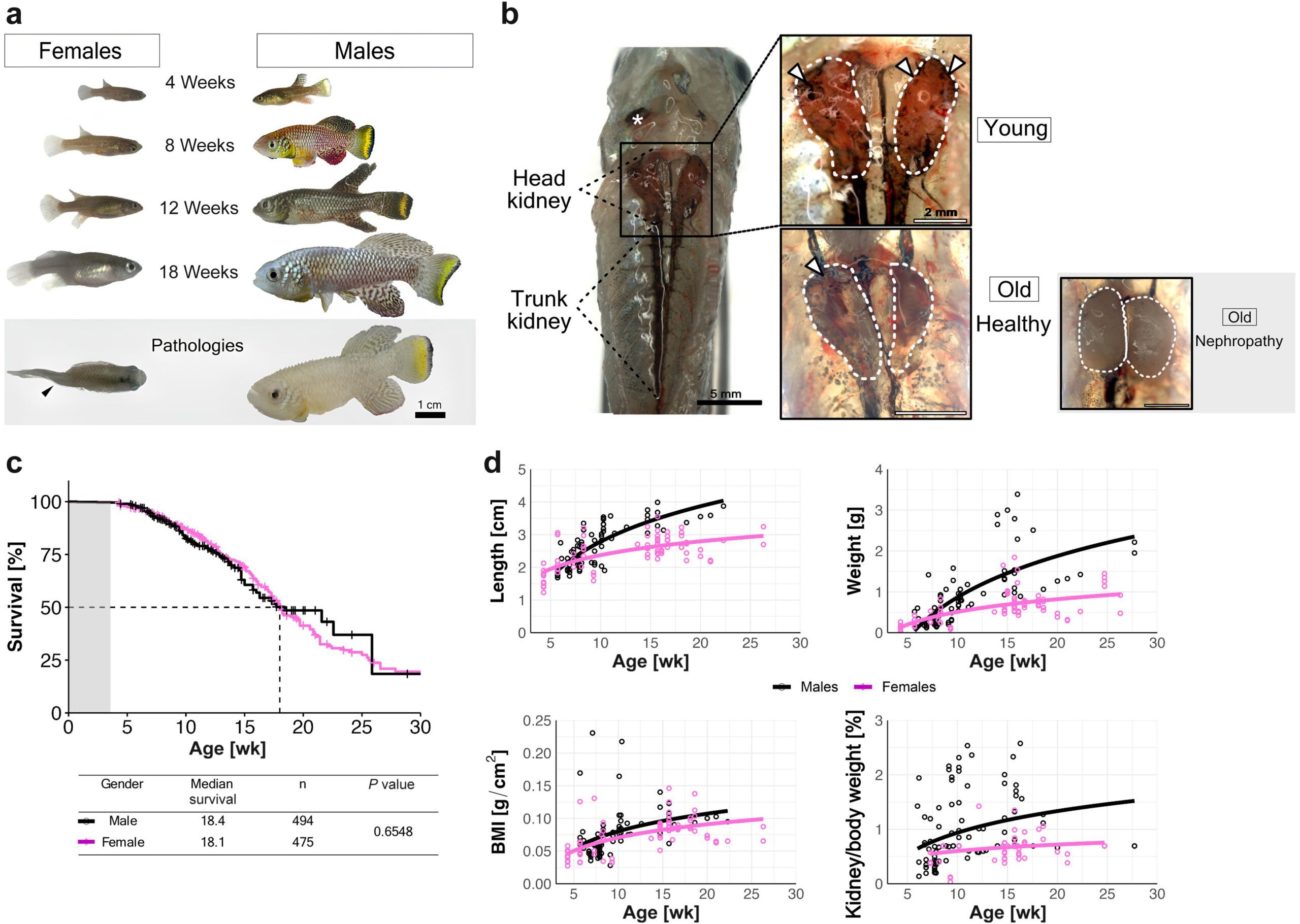

The African turquoise killifish offers a way around that barrier. This small vertebrate completes its entire lifespan in four to six months. During that short time, its organs undergo changes that closely resemble aging in humans. By watching kidney decline happen rapidly, scientists gain a rare chance to observe aging as it unfolds.

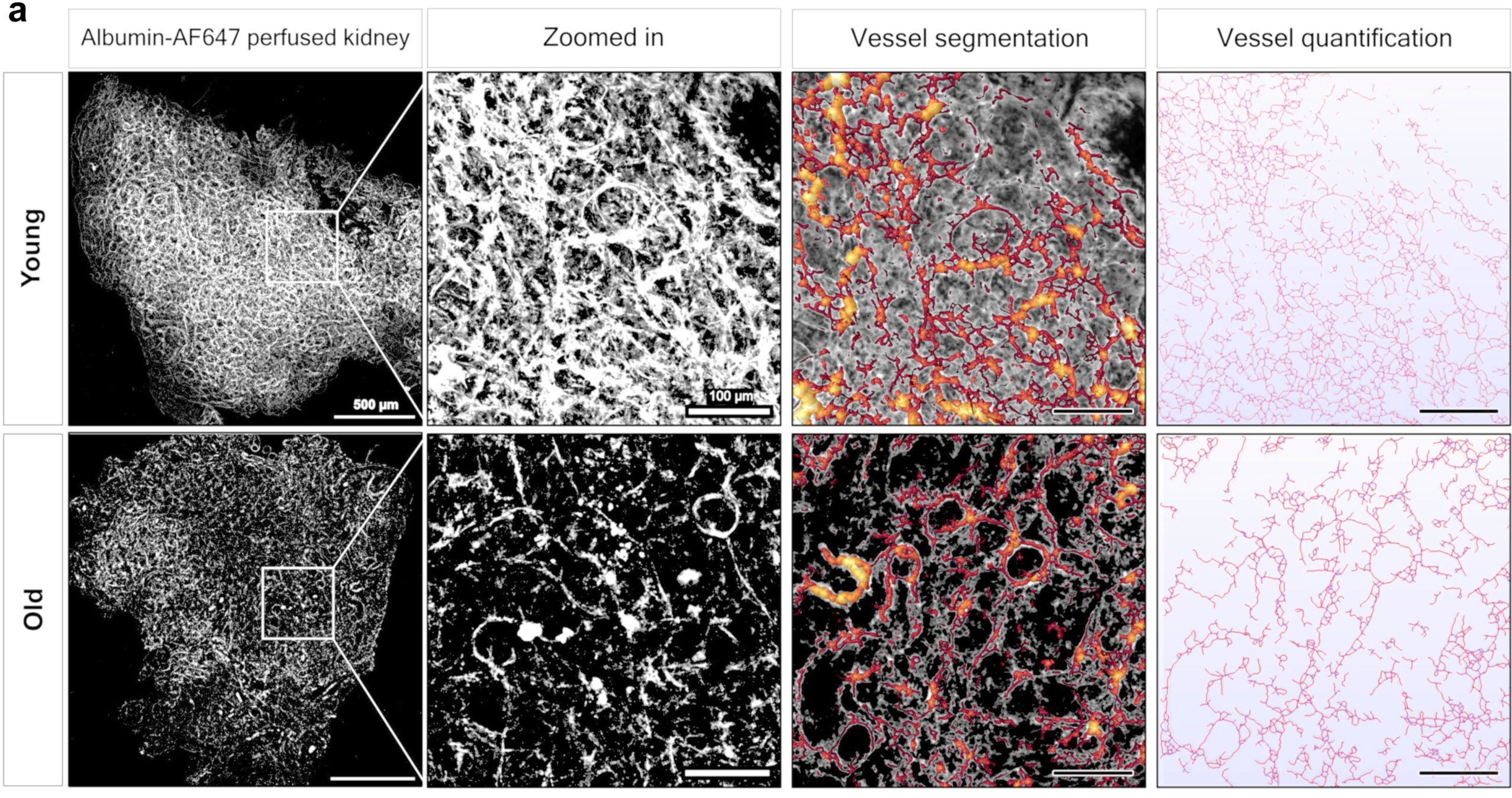

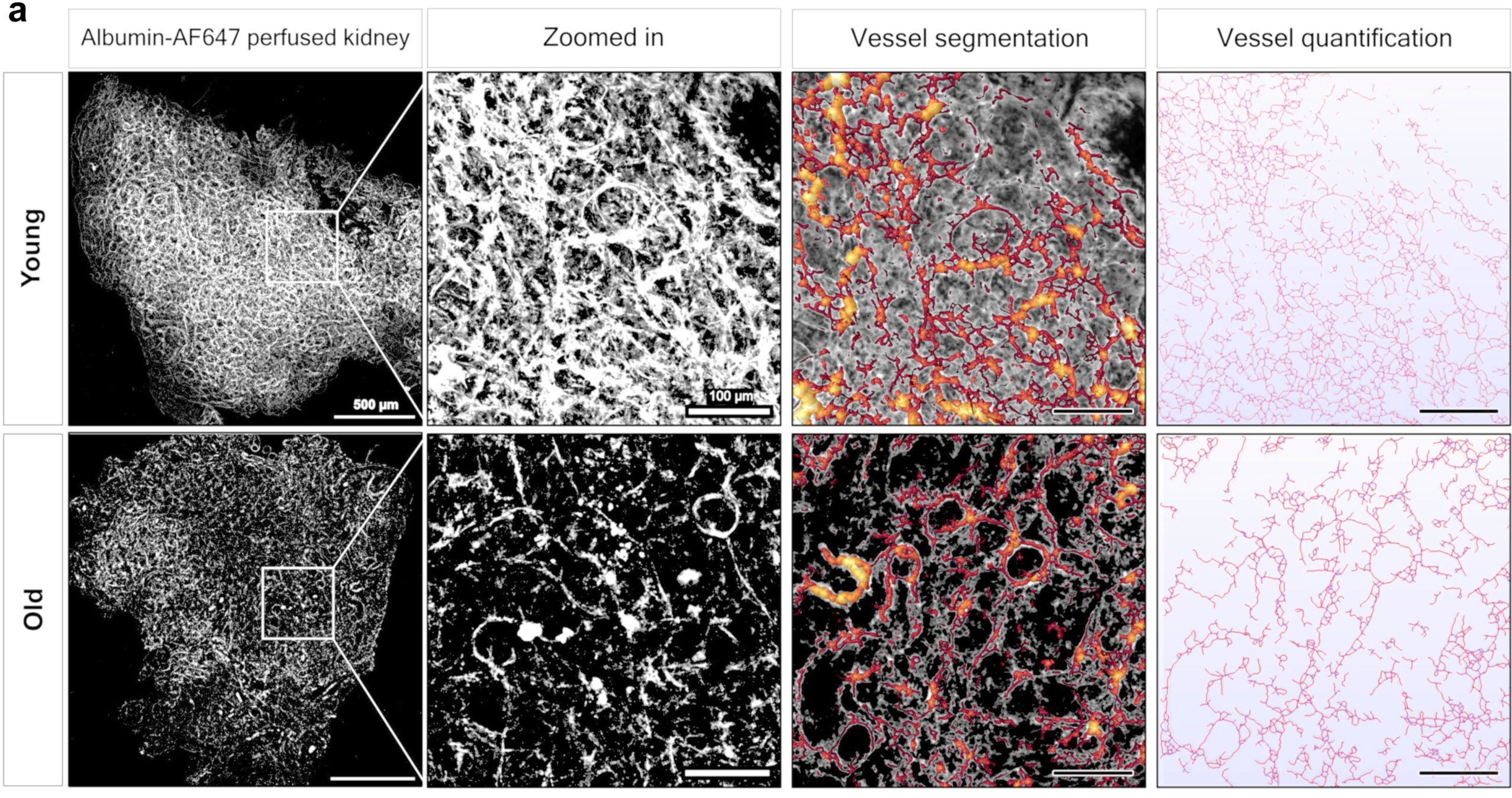

When researchers compared young and old killifish, the contrast was striking. Young kidneys were dense with tiny blood vessels that twisted through the tissue like a living web. In older fish, many of those vessels had vanished. The remaining network looked thin and broken, closely resembling aging kidneys in people.

This loss mattered. With fewer blood vessels, the kidney struggled to filter blood properly. Protein began leaking into the urine, a classic warning sign of kidney damage. The transport systems inside kidney tubules also weakened, reducing the organ’s ability to reclaim water and nutrients.

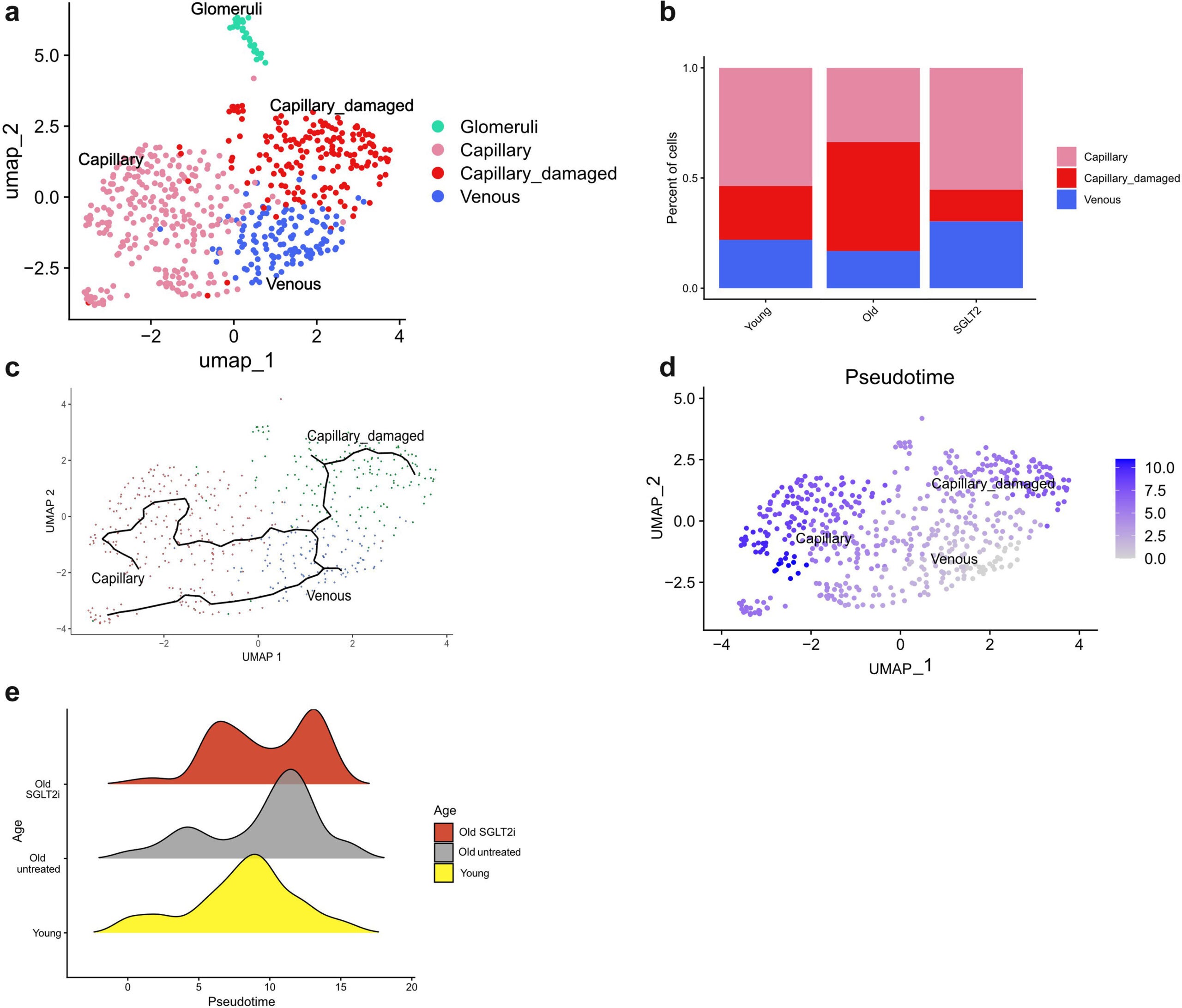

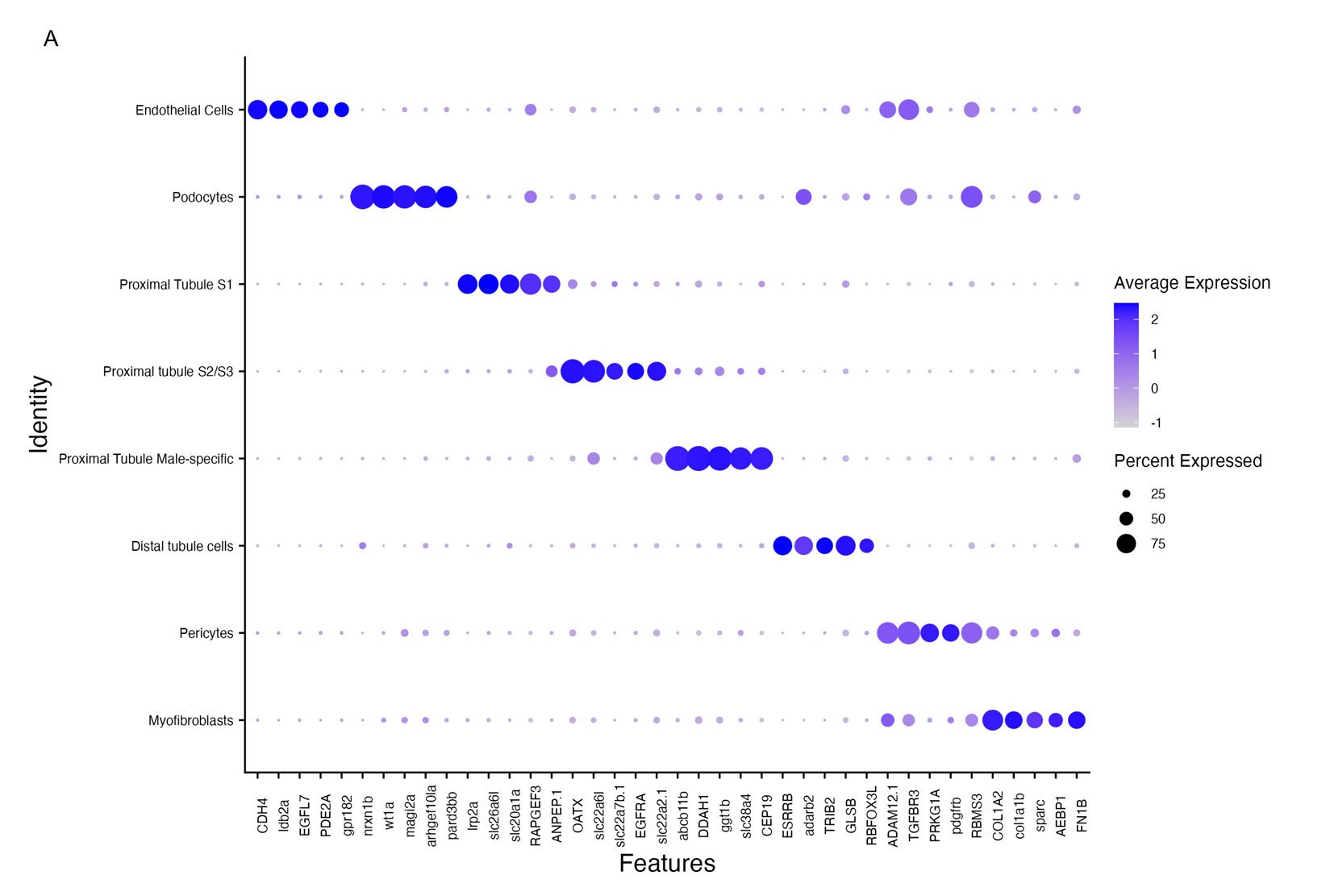

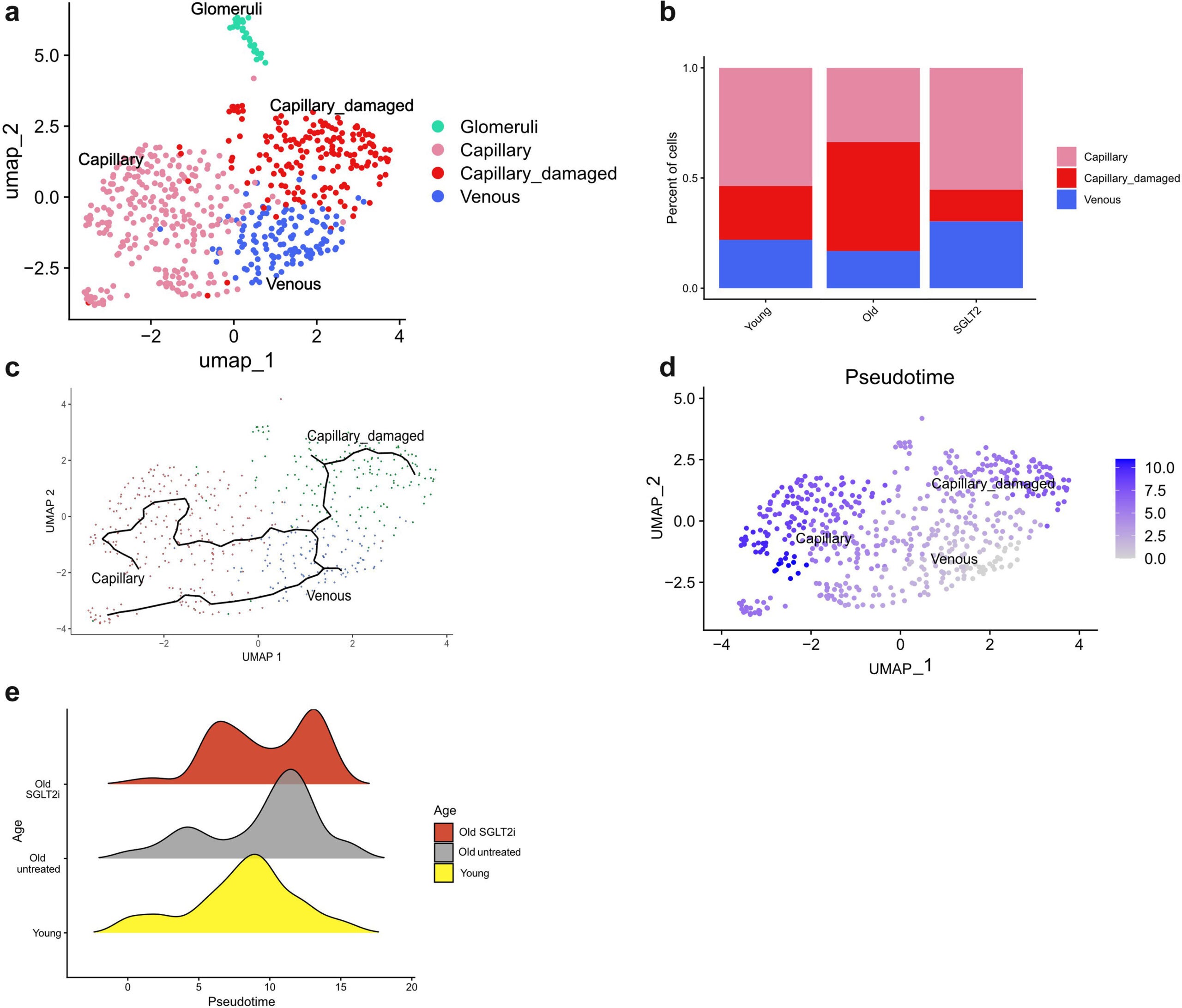

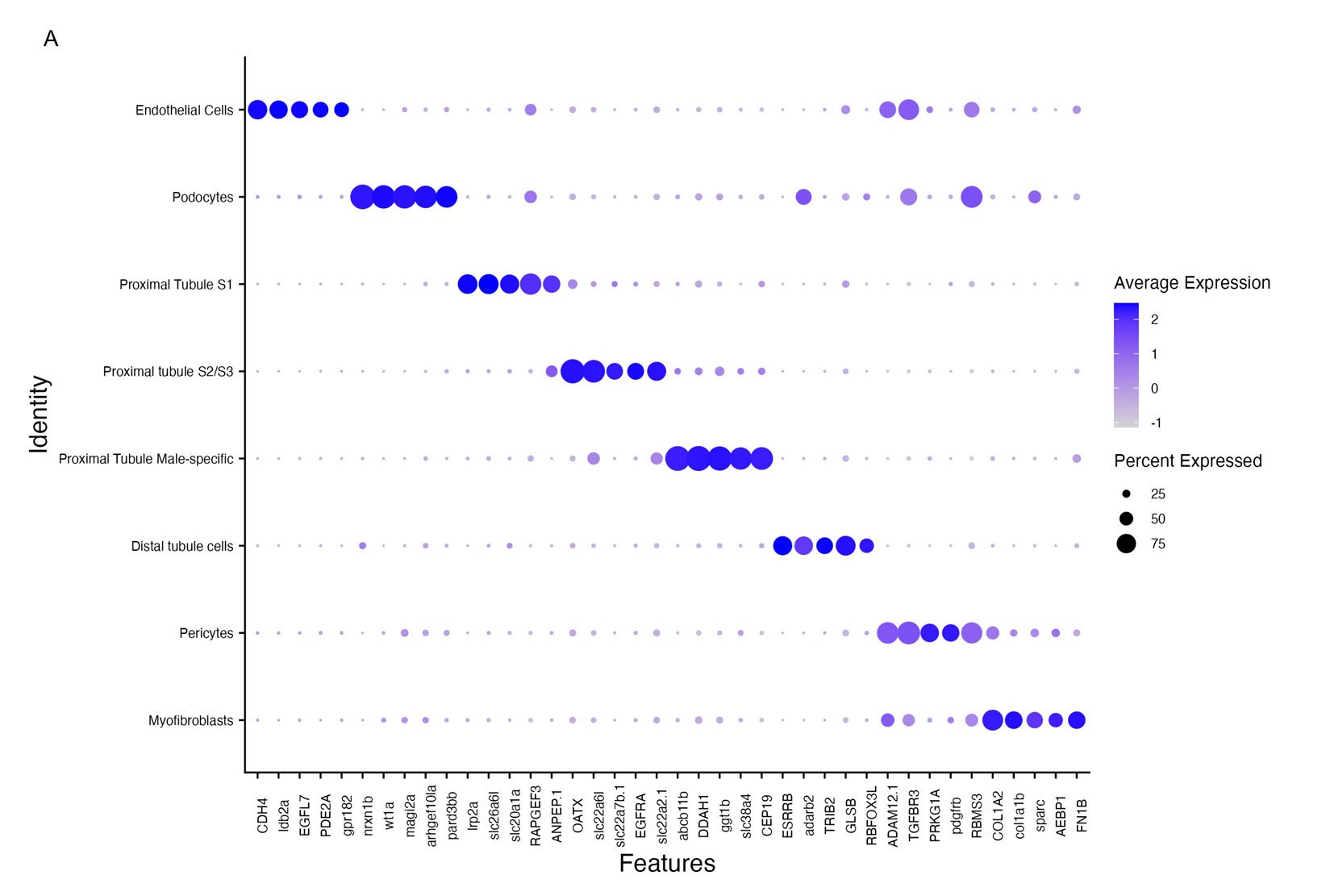

At the cellular level, aging kidneys showed deeper trouble. Cells changed how they produced energy. Younger kidney cells relied on an efficient system powered by mitochondria. Older cells shifted toward a less efficient process that left them with less energy to repair damage or maintain structure.

Inflammation also rose sharply. Genetic analysis showed that many genes linked to inflammation and aging became more active over time. At the same time, communication between different kidney cell types declined. Cells that once coordinated repair and balance no longer worked together as effectively.

The research team then asked a critical question: Could a drug already used in human medicine slow this decline?

They focused on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, known as SGLT2 inhibitors. Doctors often prescribe these drugs to treat type 2 diabetes.

Over the past decade, large clinical trials have shown that they also protect the kidneys and heart, even in patients without diabetes. One such drug, dapagliflozin, was given to killifish throughout their lives. The results revealed how the drug works at a deeper level than previously understood.

Fish that received the treatment retained far more of their kidney blood vessels as they aged. Capillary density stayed higher, and the overall structure of the kidney looked healthier compared with untreated fish.

Energy production inside kidney cells also improved. Gene activity patterns in treated fish resembled those seen in much younger animals. Inflammatory signals dropped, and communication between different cell types partially recovered.

Perhaps most importantly, protein leakage into the urine declined. Even late in life, treated fish maintained stronger kidney filtration. While the drug did not extend the fish’s lifespan, it clearly slowed the aging of the kidneys themselves.

These findings help explain a puzzle that has followed SGLT2 inhibitors for years. Their kidney benefits often seem too large to be explained by blood sugar control alone. This study shows that the drugs protect the kidney’s physical framework.

By preserving blood vessels, supporting energy production, and calming inflammation, SGLT2 inhibitors help maintain the environment kidneys need to function. Aging, it turns out, is not just about time passing. It is about whether cells can keep communicating, repairing, and adapting.

The study also confirms that kidney aging is not a fixed process. It can be slowed. That insight opens new doors for treatment strategies focused on maintaining organ health rather than simply reacting to failure.

Beyond the drug itself, the killifish model may prove transformative. Its rapid aging allows scientists to observe long-term processes in weeks instead of years. That speed could accelerate the search for therapies that protect organs as the body grows older.

Researchers plan to test whether starting SGLT2 treatment later in life can reverse existing damage. They also want to explore how timing and dosage affect outcomes. These studies could guide future clinical trials aimed at preserving kidney health in older adults.

The work suggests that understanding aging requires looking beyond genes alone. Physical structures, energy systems, and cell cooperation all play essential roles.

This research may influence how kidney aging and chronic kidney disease are approached in the future. By showing how SGLT2 inhibitors protect kidney structure, the study supports their broader use in patients at risk of kidney decline.

It also provides scientists with a fast, reliable model to test new treatments aimed at slowing organ aging. In the long term, this approach could help people maintain kidney function longer, reduce the need for dialysis, and improve quality of life as populations age.

Research findings are available online in the journal Kidney International.

The original story “Fast-aging fish reveals how kidneys age and how a common drug protects them” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Fast-aging fish reveals how kidneys age and how a common drug protects them appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Kidney aging rarely draws attention until something goes wrong. Over time, these organs quietly lose strength, filter less efficiently, and struggle to keep the body balanced. A new study now brings kidney aging into sharp focus by turning to an unlikely helper; a tiny fish that lives its entire life in just a few months.

Scientists reveal how the African turquoise killifish mirrors the aging process of human kidneys at remarkable speed. The work also uncovers how a widely prescribed drug can protect aging kidneys by preserving their delicate blood vessels and cellular health. Together, these findings may reshape how kidney aging is studied and treated.

Kidneys play a constant, demanding role in daily life. They clean waste from the blood, control fluid levels, and help regulate blood pressure. As you age, these tasks become harder. Tiny blood vessels inside the kidneys slowly disappear, a process known as vascular rarefaction. This loss weakens filtration and raises the risk of chronic kidney disease.

Studying this slow decline has long frustrated researchers. In humans, kidney aging unfolds over decades. Even in laboratory mice, it can take years. That long timeline makes experiments costly and limits how many potential treatments can be tested.

The African turquoise killifish offers a way around that barrier. This small vertebrate completes its entire lifespan in four to six months. During that short time, its organs undergo changes that closely resemble aging in humans. By watching kidney decline happen rapidly, scientists gain a rare chance to observe aging as it unfolds.

When researchers compared young and old killifish, the contrast was striking. Young kidneys were dense with tiny blood vessels that twisted through the tissue like a living web. In older fish, many of those vessels had vanished. The remaining network looked thin and broken, closely resembling aging kidneys in people.

This loss mattered. With fewer blood vessels, the kidney struggled to filter blood properly. Protein began leaking into the urine, a classic warning sign of kidney damage. The transport systems inside kidney tubules also weakened, reducing the organ’s ability to reclaim water and nutrients.

At the cellular level, aging kidneys showed deeper trouble. Cells changed how they produced energy. Younger kidney cells relied on an efficient system powered by mitochondria. Older cells shifted toward a less efficient process that left them with less energy to repair damage or maintain structure.

Inflammation also rose sharply. Genetic analysis showed that many genes linked to inflammation and aging became more active over time. At the same time, communication between different kidney cell types declined. Cells that once coordinated repair and balance no longer worked together as effectively.

The research team then asked a critical question: Could a drug already used in human medicine slow this decline?

They focused on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, known as SGLT2 inhibitors. Doctors often prescribe these drugs to treat type 2 diabetes.

Over the past decade, large clinical trials have shown that they also protect the kidneys and heart, even in patients without diabetes. One such drug, dapagliflozin, was given to killifish throughout their lives. The results revealed how the drug works at a deeper level than previously understood.

Fish that received the treatment retained far more of their kidney blood vessels as they aged. Capillary density stayed higher, and the overall structure of the kidney looked healthier compared with untreated fish.

Energy production inside kidney cells also improved. Gene activity patterns in treated fish resembled those seen in much younger animals. Inflammatory signals dropped, and communication between different cell types partially recovered.

Perhaps most importantly, protein leakage into the urine declined. Even late in life, treated fish maintained stronger kidney filtration. While the drug did not extend the fish’s lifespan, it clearly slowed the aging of the kidneys themselves.

These findings help explain a puzzle that has followed SGLT2 inhibitors for years. Their kidney benefits often seem too large to be explained by blood sugar control alone. This study shows that the drugs protect the kidney’s physical framework.

By preserving blood vessels, supporting energy production, and calming inflammation, SGLT2 inhibitors help maintain the environment kidneys need to function. Aging, it turns out, is not just about time passing. It is about whether cells can keep communicating, repairing, and adapting.

The study also confirms that kidney aging is not a fixed process. It can be slowed. That insight opens new doors for treatment strategies focused on maintaining organ health rather than simply reacting to failure.

Beyond the drug itself, the killifish model may prove transformative. Its rapid aging allows scientists to observe long-term processes in weeks instead of years. That speed could accelerate the search for therapies that protect organs as the body grows older.

Researchers plan to test whether starting SGLT2 treatment later in life can reverse existing damage. They also want to explore how timing and dosage affect outcomes. These studies could guide future clinical trials aimed at preserving kidney health in older adults.

The work suggests that understanding aging requires looking beyond genes alone. Physical structures, energy systems, and cell cooperation all play essential roles.

This research may influence how kidney aging and chronic kidney disease are approached in the future. By showing how SGLT2 inhibitors protect kidney structure, the study supports their broader use in patients at risk of kidney decline.

It also provides scientists with a fast, reliable model to test new treatments aimed at slowing organ aging. In the long term, this approach could help people maintain kidney function longer, reduce the need for dialysis, and improve quality of life as populations age.

Research findings are available online in the journal Kidney International.

The original story “Fast-aging fish reveals how kidneys age and how a common drug protects them” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Fast-aging fish reveals how kidneys age and how a common drug protects them appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.