The human body moves through a coordinated effort of skeletal muscles, working in concert to generate force. While some muscles align in a single direction, others form intricate patterns, enabling complex motion.

Engineers and scientists have long been interested in replicating these natural movements in artificial systems, particularly for soft robotics and medical applications. Traditional robotic actuators rely on rigid mechanical parts, but biohybrid robots powered by lab-grown muscle tissue could offer an alternative, allowing for flexible, energy-efficient motion.

However, engineering artificial muscle tissue with the ability to contract in multiple directions has remained a significant challenge. Most lab-grown muscle fibers have been unidirectional, limiting their ability to mimic the complex movements seen in nature.

Now, researchers at MIT have developed a breakthrough method that allows muscle tissues to contract in multiple, coordinated directions.

Their approach, called “simple templating of actuators via micro-topographical patterning” (STAMP), uses a cost-effective and scalable method to guide muscle cell growth along microscopic patterns, allowing for precise alignment of muscle fibers. This advancement opens the door for biohybrid robots with improved functionality and for medical applications in tissue engineering.

For decades, artificial muscle research has focused on aligning muscle fibers in a single direction. Typically, 3D muscle tissues are tensioned between two posts, achieving global alignment along the axis of imposed tension.

While this method allows for contraction measurement and functional monitoring, it does not replicate the multi-directional architecture seen in natural muscle groups such as the iris, which enables pupil dilation and constriction.

Previous attempts to create aligned 2D muscle monolayers have faced several hurdles. Muscle monolayers on rigid surfaces often delaminate within days, making long-term studies difficult.

Related Stories

Early efforts to pattern adhesion-promoting proteins such as fibronectin, gelatin, and Matrigel on glass and plastic substrates provided some alignment but failed to maintain contractility over extended periods.

Alternative methods using rigid microfabricated scaffolds with grooves have been more successful but require complex microfabrication facilities, limiting their accessibility. Additionally, many of these methods rely on non-transparent materials, which interfere with live-cell imaging crucial for studying muscle function and drug responses.

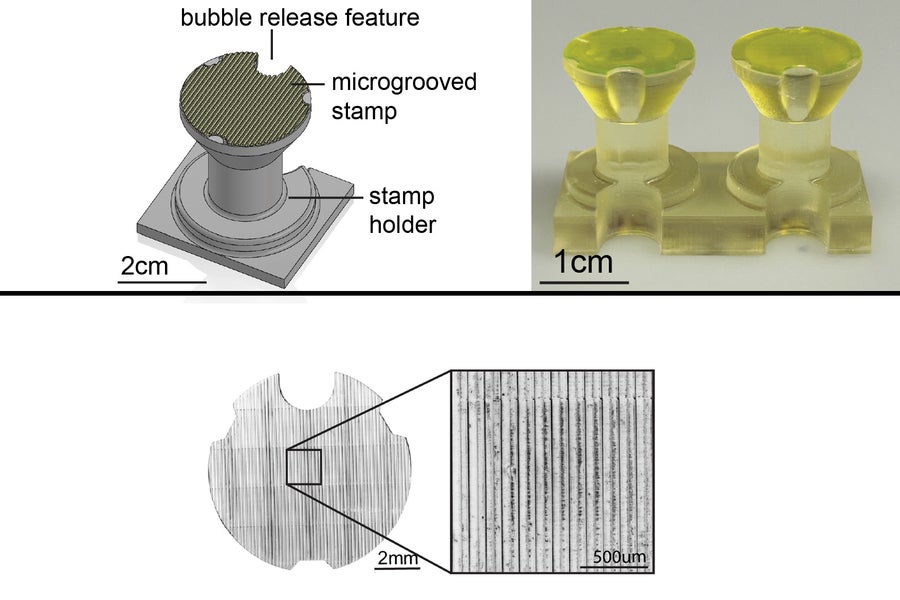

MIT researchers tackled these limitations by developing STAMP, a simple and scalable method to precisely pattern contractile muscle fibers in hydrogels. Using 3D-printed stamps, they created microscopic grooves in soft hydrogels, which mimic the natural extracellular matrix environment of muscle cells.

This approach allows muscle fibers to grow in complex, multi-directional architectures while retaining their ability to generate force. Unlike previous methods, STAMP does not require expensive microfabrication equipment or rigid scaffolds, making it a practical solution for a wide range of applications.

To showcase the versatility of their method, the researchers designed an artificial iris using STAMP. The human iris consists of two sets of muscles: concentric fibers that contract inward and radial fibers that expand outward, controlling pupil size.

The team 3D-printed a stamp with microscopic grooves mimicking this architecture and pressed it into a hydrogel. Mouse muscle cells genetically engineered to respond to light were then seeded onto the patterned hydrogel. Over time, these cells aligned along the grooves and formed a functional muscle layer capable of contracting in multiple directions.

When stimulated with light pulses, the artificial iris constricted and expanded, closely mimicking natural iris function. The results matched computational predictions, demonstrating the potential of STAMP in designing biohybrid robots with complex, multi-degree-of-freedom motion.

Unlike previous muscle-powered robots that could only perform simple movements like gripping or walking, this approach enables more sophisticated mechanical actions, paving the way for soft robots capable of intricate tasks.

Ritu Raman, the Eugene Bell Career Development Professor of Tissue Engineering at MIT, emphasized the significance of this breakthrough. “With the iris design, we believe we have demonstrated the first skeletal muscle-powered robot that generates force in more than one direction. That was uniquely enabled by this stamp approach,” she said.

Beyond robotics, this method has implications for tissue engineering. “We want to make tissues that replicate the architectural complexity of real tissues. To do that, you really need this kind of precision in your fabrication,” Raman added.

The ability to precisely control muscle alignment in engineered tissues has profound implications beyond robotics. One key application is in drug screening for neuromuscular diseases. Current in-vitro models struggle to replicate the structural complexity of natural muscle, making it difficult to evaluate treatments effectively. With STAMP, researchers can create more physiologically relevant muscle models, improving the reliability of drug testing.

Another potential application is in regenerative medicine. Muscle loss due to injury, disease, or aging presents significant challenges in healthcare. Bioengineered muscle tissues grown using STAMP could be used in reconstructive therapies, restoring function to damaged muscle groups. The ability to precisely guide muscle fiber orientation is crucial for ensuring proper integration with existing tissues.

Soft robotics is another area poised to benefit from this technology. Traditional robots rely on rigid components, which limit their adaptability. Biohybrid robots powered by engineered muscle tissue could offer a flexible, biodegradable alternative.

“Instead of using rigid actuators that are typical in underwater robots, if we can use soft biological robots, we can navigate and be much more energy-efficient, while also being completely biodegradable and sustainable,” Raman explained.

The researchers anticipate that their stamping technique could be applied to other types of cells, including neurons and cardiac muscle cells, potentially leading to advances in bioelectronics and heart tissue engineering. While the team used high-precision 3D printing to fabricate their stamps, Raman noted that conventional tabletop printers could also produce them, making the approach widely accessible.

“In this work, we wanted to show we can use this stamp approach to make a ‘robot’ that can do things that previous muscle-powered robots can’t do,” she said. “We chose to work with skeletal muscle cells. But there’s nothing stopping you from doing this with any other cell type.”

MIT’s breakthrough in engineered muscle tissue marks a significant step forward in biohybrid robotics and tissue engineering. By simplifying the process of aligning muscle fibers in complex orientations, STAMP provides researchers with a powerful tool for creating artificial tissues that more closely resemble their natural counterparts.

From improving drug testing models to developing next-generation soft robots, this method has the potential to drive innovation across multiple fields.

The study was published in Biomaterials Science, with contributions from researchers at MIT and Tel Aviv University. As the technology continues to advance, the team plans to explore new muscle architectures and activation methods, further expanding the possibilities of bioengineered muscle-powered systems.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post First-ever multi-directional artificial muscles could revolutionize robotics appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.