Most people have the Epstein-Barr (EBV) virus. Sometimes people are unaware of this virus in their body; it settles into immune cells and remains for the duration. Although EBV does not cause illness for most people (the majority of people live without any symptom or sign of being infected), for many people in the world today, including individuals with weakened immune systems, it is linked to the development of several cancers as well as serious complications.

However, a new group of antibodies produced in the laboratory may finally provide a way to inhibit the EBV virus from causing an illness.

Researchers at Fred Hutch Cancer Center have created genetic, human-type monoclonal antibodies that can prevent EBV infection in mice with human immune systems. These studies, which have been published in Cell Reports Medicine, represent a significant step forward toward developing new therapies that will protect high-risk transplant recipients and other people who may be at increased risk of developing illness as a result of EBV infection.

The Epstein-Barr virus is estimated to infect about 95% of the human population globally. It causes infectious mononucleosis. It is also linked to multiple sclerosis, autoimmune diseases, and approximately 358,000 cases of cancer each year, resulting in about 209,000 deaths.

Blocking the virus has proven to be extremely difficult.

According to Andrew McGuire, Ph.D., a biochemist and cellular biologist in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division at Fred Hutch, “We have been unsuccessful in finding any human antibodies that will prevent EBV from attaching to our immune cells. Unlike many other viruses, EBV has evolved a much broader ability to connect with virtually every single one of our B-cells.”

Therefore, Dr. McGuire and his colleagues opted to utilize new technologies to assist them in filling this knowledge gap. They were able to take an important step toward deriving an effective means of blocking one of the world’s most prevalent viruses.

EBV effectively binds to host cells by implementing a specific combination of surface proteins, based on recent research, and is therefore capable of successfully infecting and integrating into B cell populations. Gp350 and gp42 are two viral proteins that serve as molecular keys for the virus to attach to and gain entry into human immune cells.

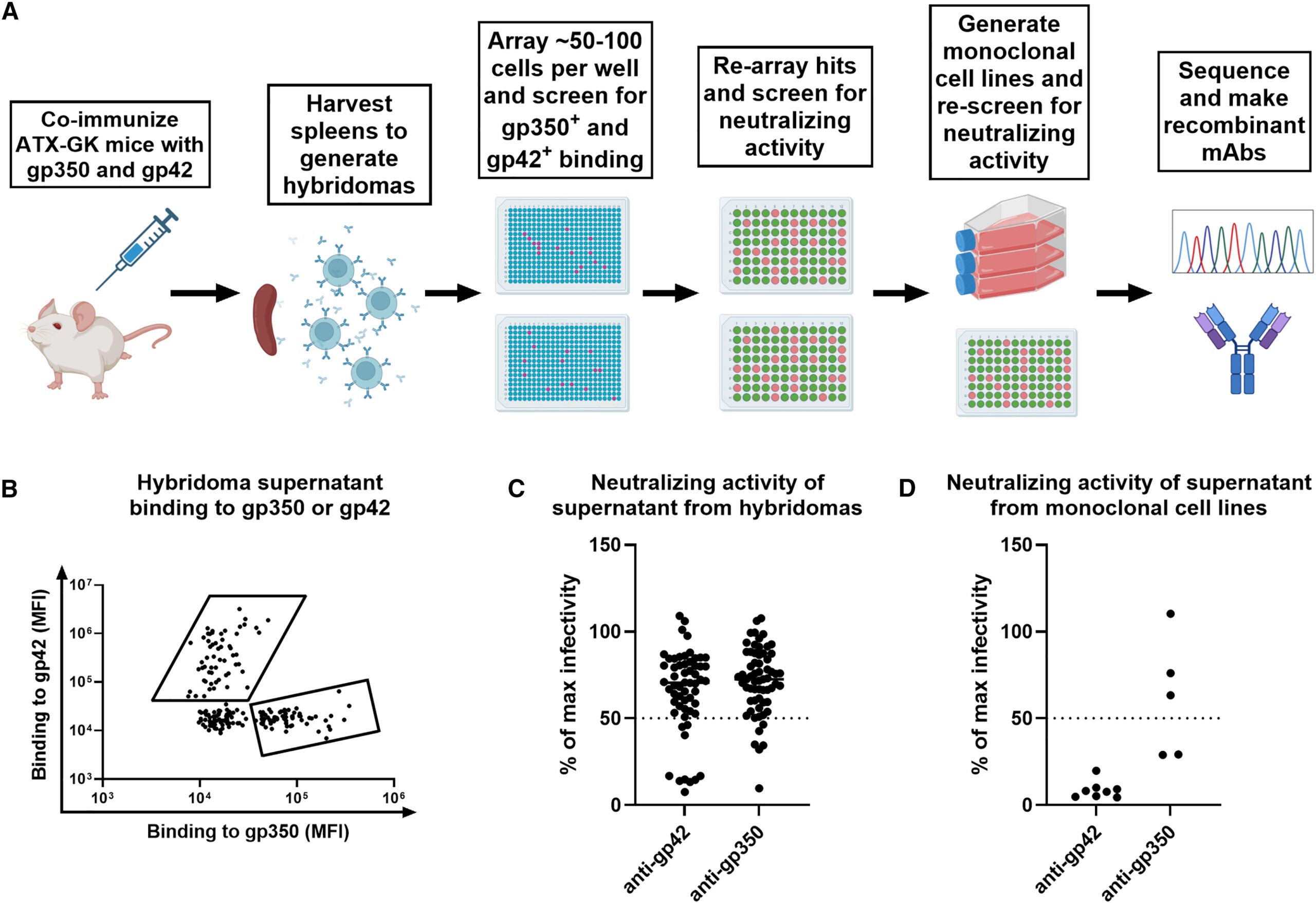

To create antibodies that could inhibit these steps, the research team used a genetically engineered mouse model that contained human antibody genes. These mice were able to produce antibodies that closely mimic the antibodies that humans would produce, which decreased the chance of future antibody-mediated immune reactions.

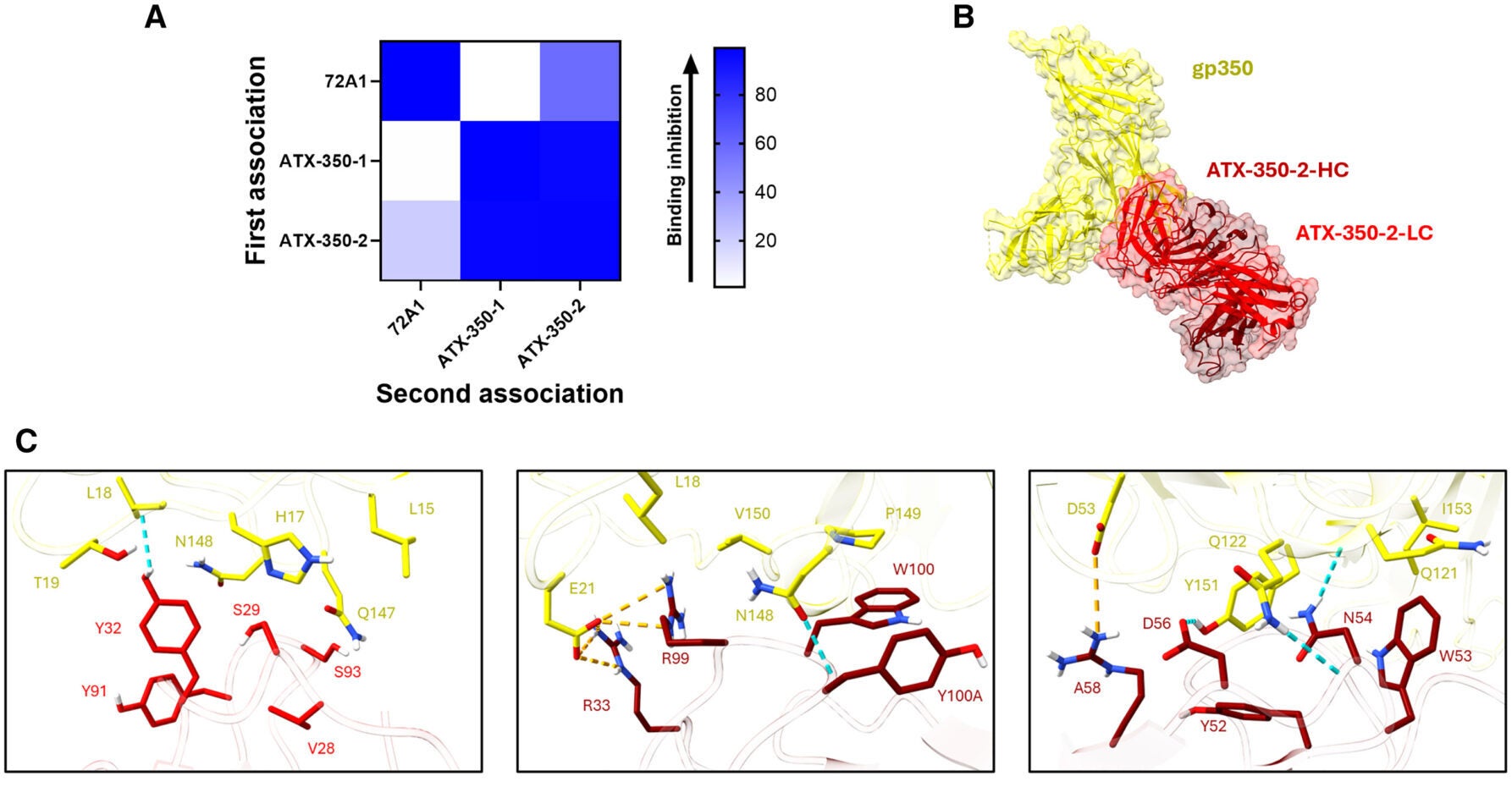

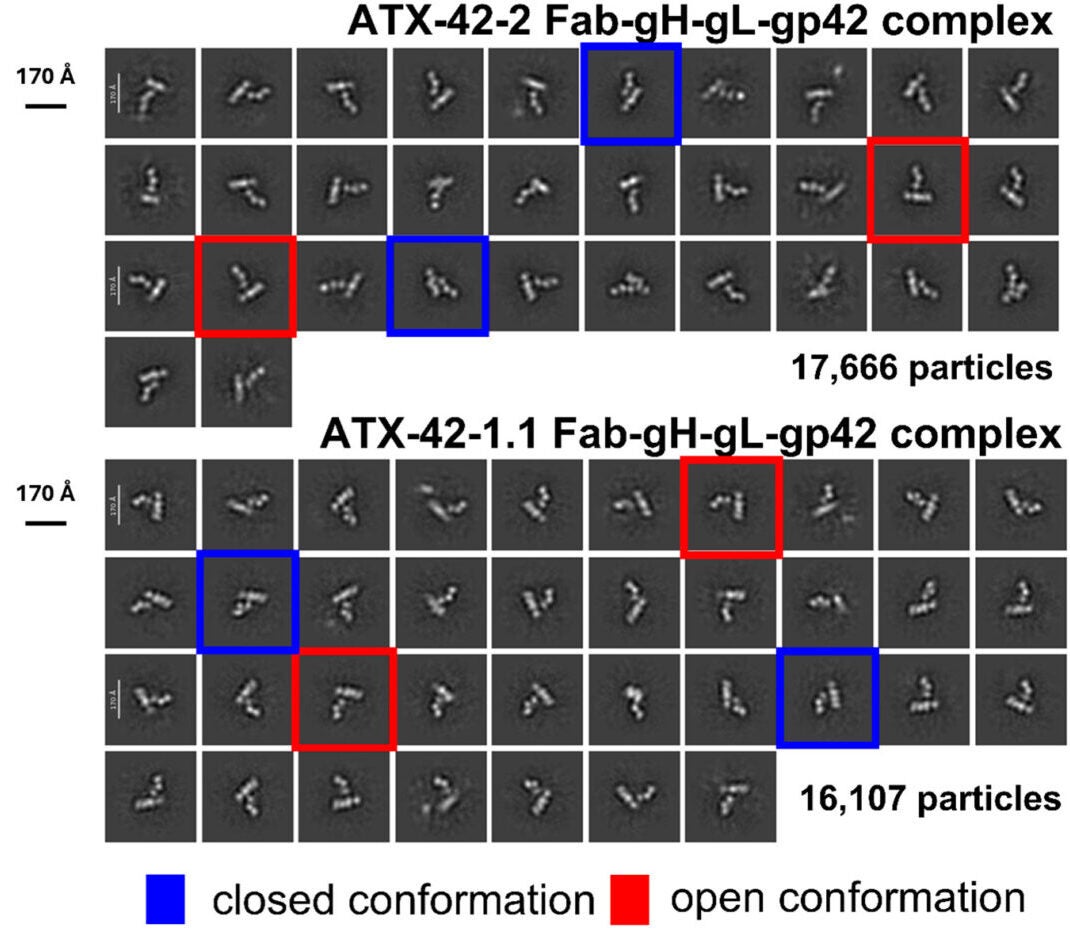

Using this method, the researchers created a total of ten different antibodies, including two antibodies against gp350 and eight antibodies against gp42. These antibodies completely blocked all viral infections of human B cells by preventing the virus from attaching to the receptors on the surface of human B cells.

Structural analysis of these antibodies also provided additional information regarding regions of the EBV-encoded proteins that could be targeted for the development of candidate vaccines.

“Through our research, we have identified many important antibodies against Epstein-Barr virus. We have also validated a new and innovative method for discovering protective antibodies against other viral pathogens,” said Crystal Chhan, a Ph.D. candidate from the University of Virginia’s McGuire Laboratory. “As a junior scientist, the results of our work were extremely gratifying, and I have a newfound respect for the field of science due to the many unexpected results that we encountered.”

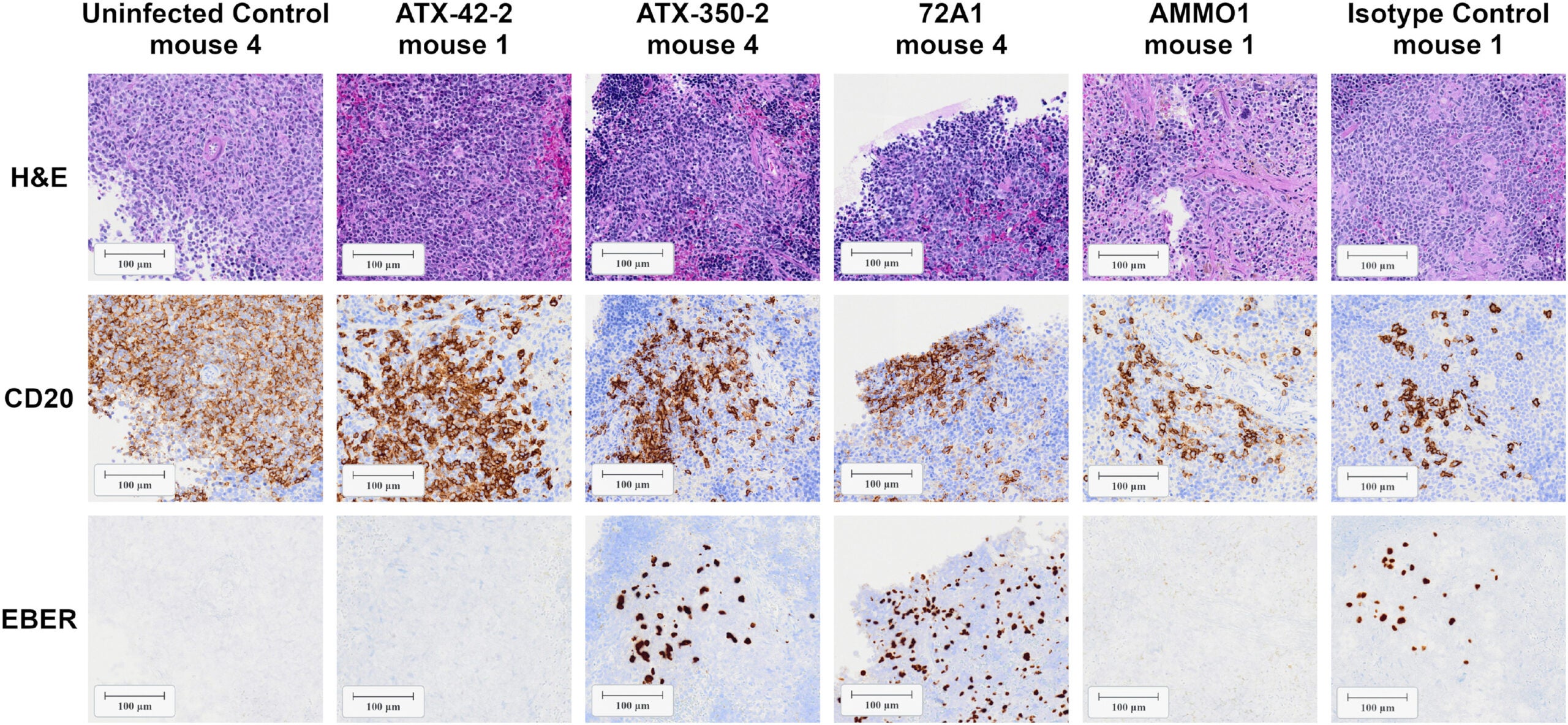

Of the antibody candidates, the most promising one was found to be the antibody to gp42, which is a protein needed for EBV to successfully enter immune cells. In studies using humanized mice (mice that contain human immune systems), infusion of this antibody provided mice with significant protection from EBV after being exposed to the virus.

Evidence suggests potential clinical utility for patients receiving organ and/or marrow transplants.

Approximately 128,000 people in the United States will receive solid organ or bone marrow transplants each year. By taking medications to suppress the immune system (e.g., immunosuppressants), these patients permit EBV to either reactivate or become widespread.

One of the most significant complications of this is called post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), which is a form of aggressive lymphoma usually associated with EBV.

“Post-Transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorders (PTLD), most of which are EBV-associated lymphomas, are common sources of both morbidity and mortality following organ transplantation,” says Rachel Bender Ignacio, MD, MPH, Associate Professor and Infectious Disease Specialist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“The ability to prevent EBV viremia may substantially reduce the incidence of PTLD while lessening the need to lessen immunosuppressive therapy, ultimately supporting continued function of transplants and enhancing patient outcomes. Therefore, the development of a way to prevent EBV viremia is one of the most significant unmet needs in transplant medicine,” she added.

Because many children who receive transplants have not previously been exposed to EBV, and therefore do not have immunity to the virus, it is anticipated that they will benefit even more than adults.

In spite of the encouraging results of this study, a number of uncertainties still exist. First, the experiments utilized humanized mouse models to evaluate the efficacy of antibody treatments, which do not replicate many aspects of human infection with EBV. For example, murine epithelial cells cannot be infected with EBV, and thus the protection of the tissues from antibody treatments could not be evaluated beyond immune cells.

Second, the virus was administered via the intravenous (IV) route. Given the frequency with which EBV infections in transplant patients occur, the route of administration is likely to be different in the clinical setting.

In addition, small sample sizes and variability in antibody levels preclude a solid comparison of the two treatments.

Ultimately, it will be necessary to complete clinical trials to establish whether the antibodies are both safe and effective in humans.

Researchers believe that patients may be able to receive a prophylactic infusion of antibodies prior to or after transplant to protect against the infection and/or reactivation of EBV.

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has also filed for patent protection with respect to the antibodies and is working with several collaborators and industry partners to facilitate the continued development of the antibody treatments. Initial testing will likely include a safety study using healthy volunteers, followed by studies involving patients at high risk of developing EBV-associated PTLD.

“There has been a growing momentum to take our findings and create a therapy that will have a tremendous impact on the lives of patients receiving organ transplants,” McGuire adds. “After many, many years of searching for an effective method to prevent EBV infection, we believe this represents a large step forward for both the scientific community and those at highest risk for complications from EBV.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

The original story “First-of-its-kind antibody blocks Epstein Barr virus – carried by 95% of people” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post First-of-its-kind antibody blocks Epstein Barr virus – carried by 95% of people appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.