We rely on smell more than most people may realize. Across mammals, scent guides feeding, warns of danger, and shapes social behavior. A new international study shows that this vital sense leaves a lasting mark in bone, allowing scientists to estimate how well even extinct mammals could smell.

The research was led by Dr. Quentin Martinez and Dr. Eli Amson at the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart. Their team combined brain anatomy with genetic data to reveal a clear link between skull shape and olfactory ability. The findings were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

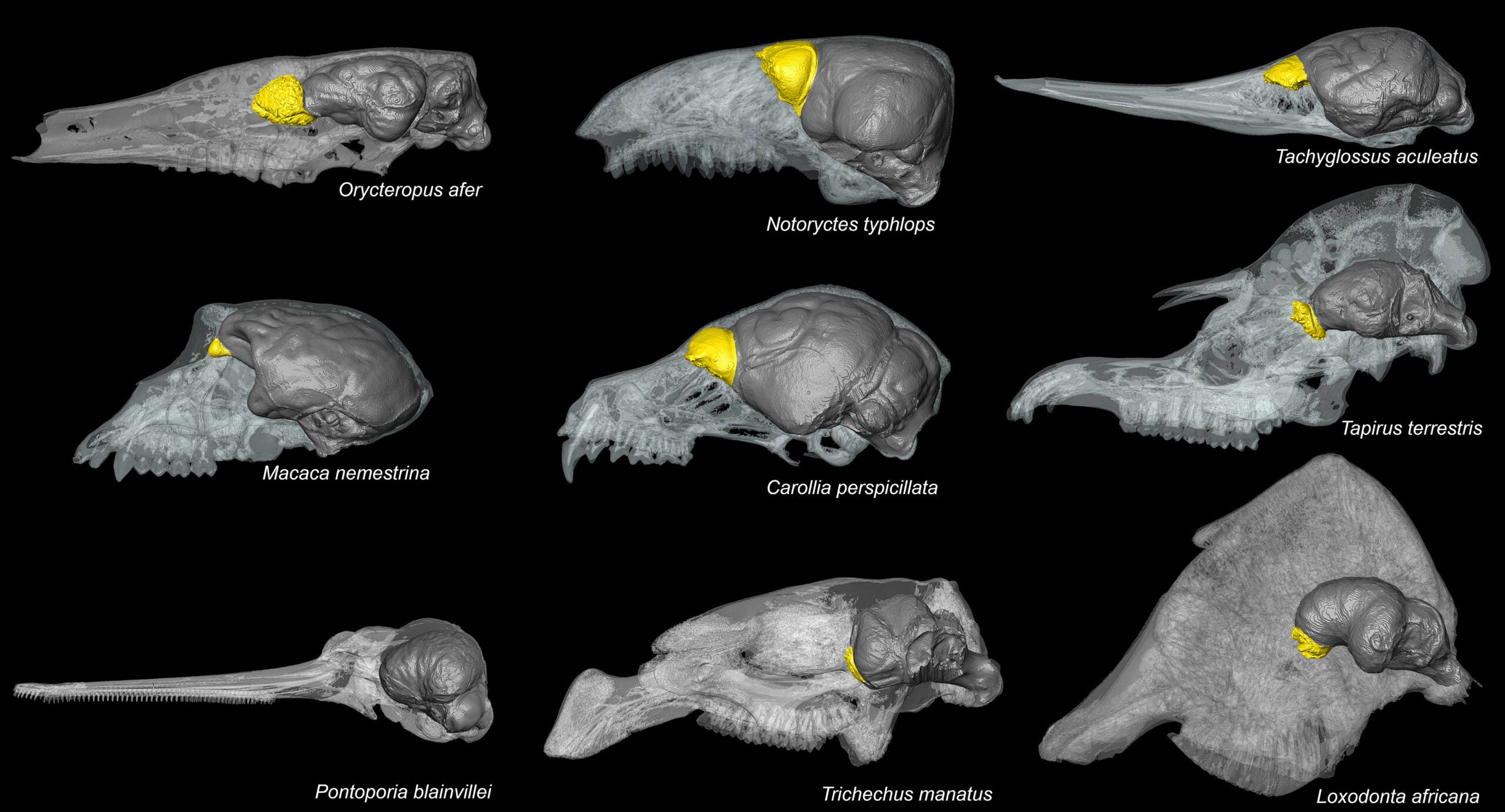

In living mammals, smell begins in the nose, where odor molecules bind to receptors. These receptors connect to neurons that send signals to the olfactory bulb, a structure at the front of the brain. Because the brain fills the skull, the shape of the braincase mirrors the brain itself. Even after soft tissue decays, this bony cavity often remains intact for millions of years.

That makes the olfactory bulb an ideal target for studying smell in fossils. “Our approach, from the brain to the genes, combines the anatomy of the skull with genetic information,” Martinez said. “This helps us to better understand the evolution of the sense of smell in mammals.”

Until now, scientists struggled to link fossil anatomy to real sensory ability. DNA does not survive deep time. But bones do, and the new study shows they hold more information than expected.

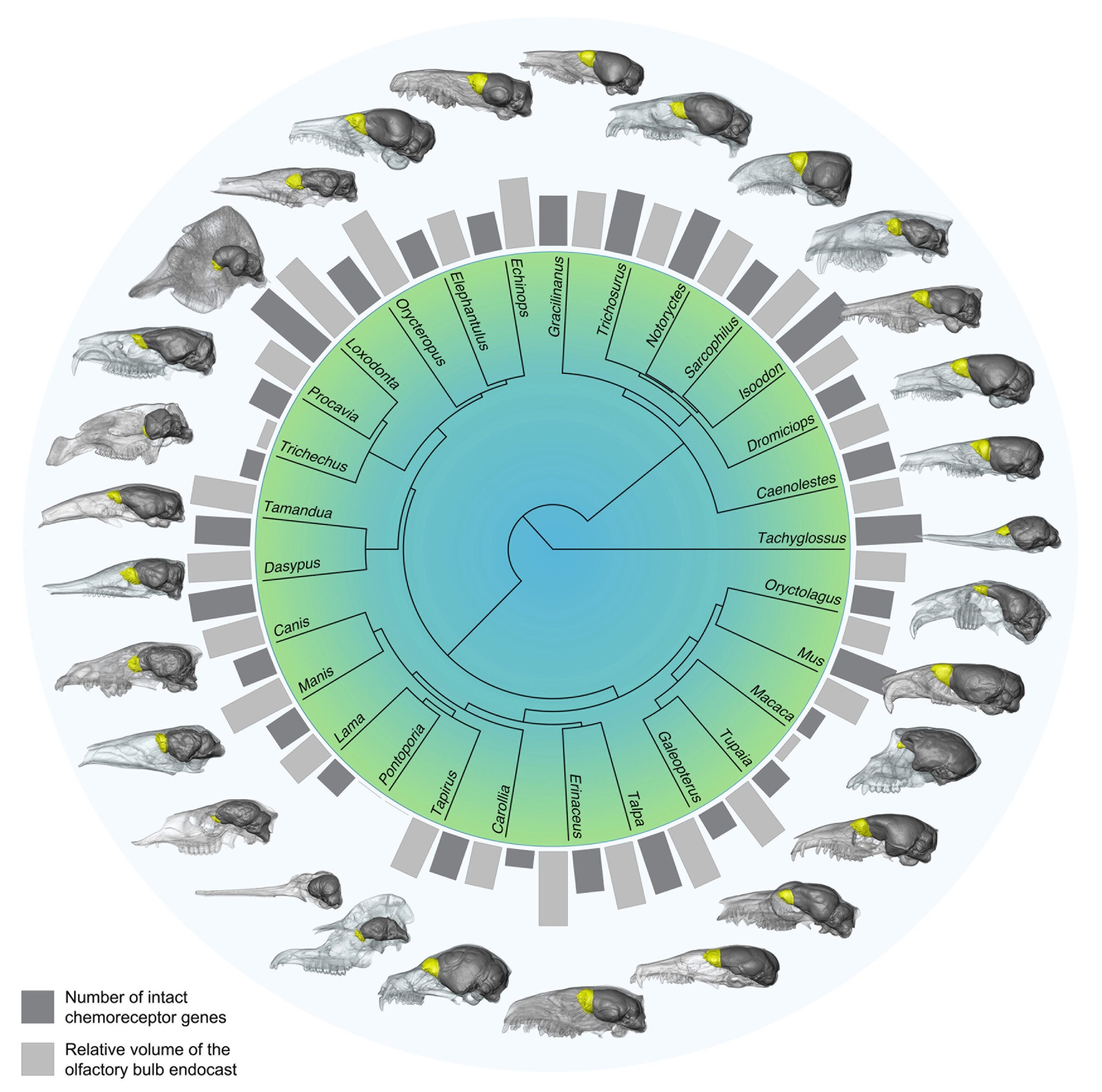

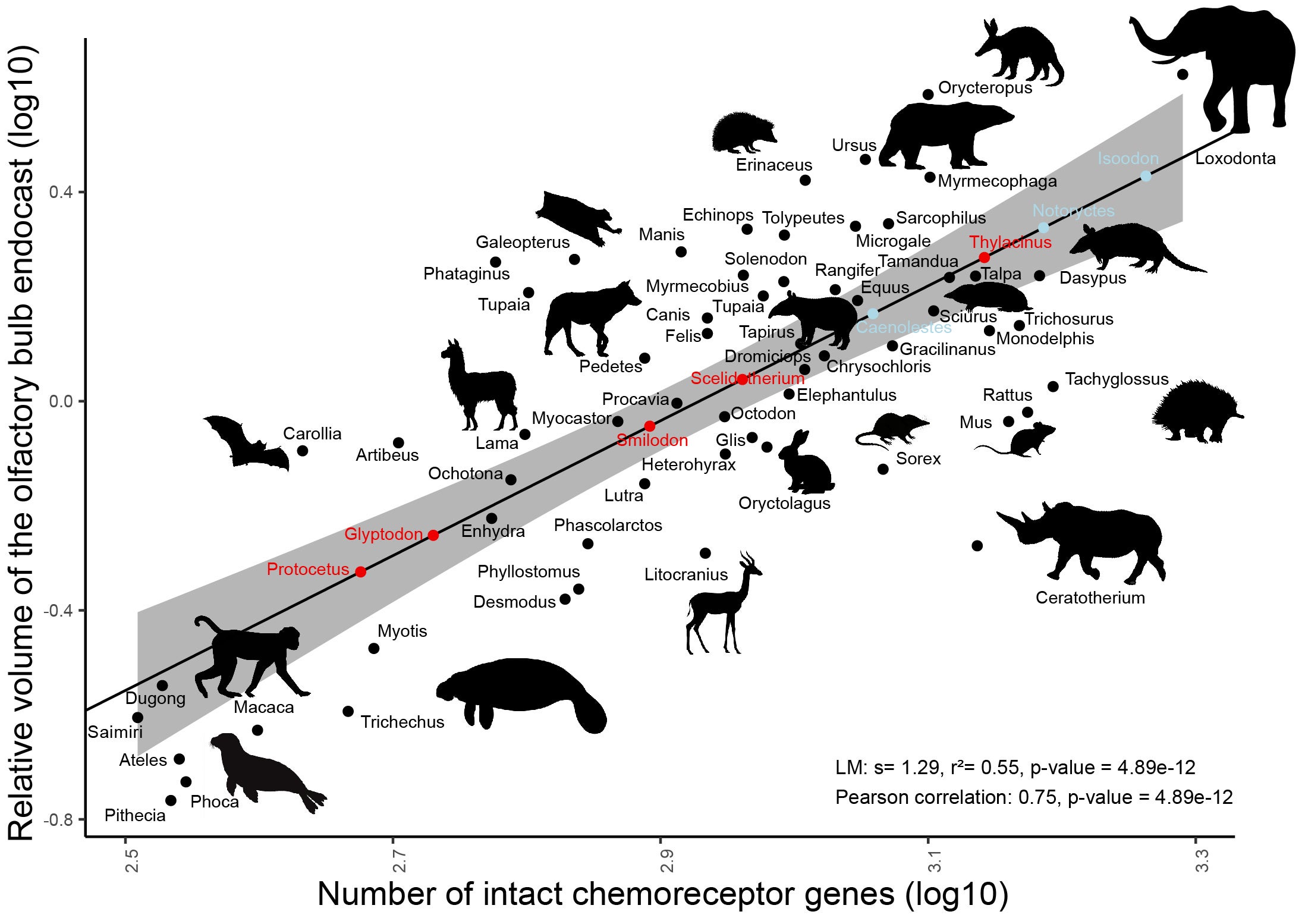

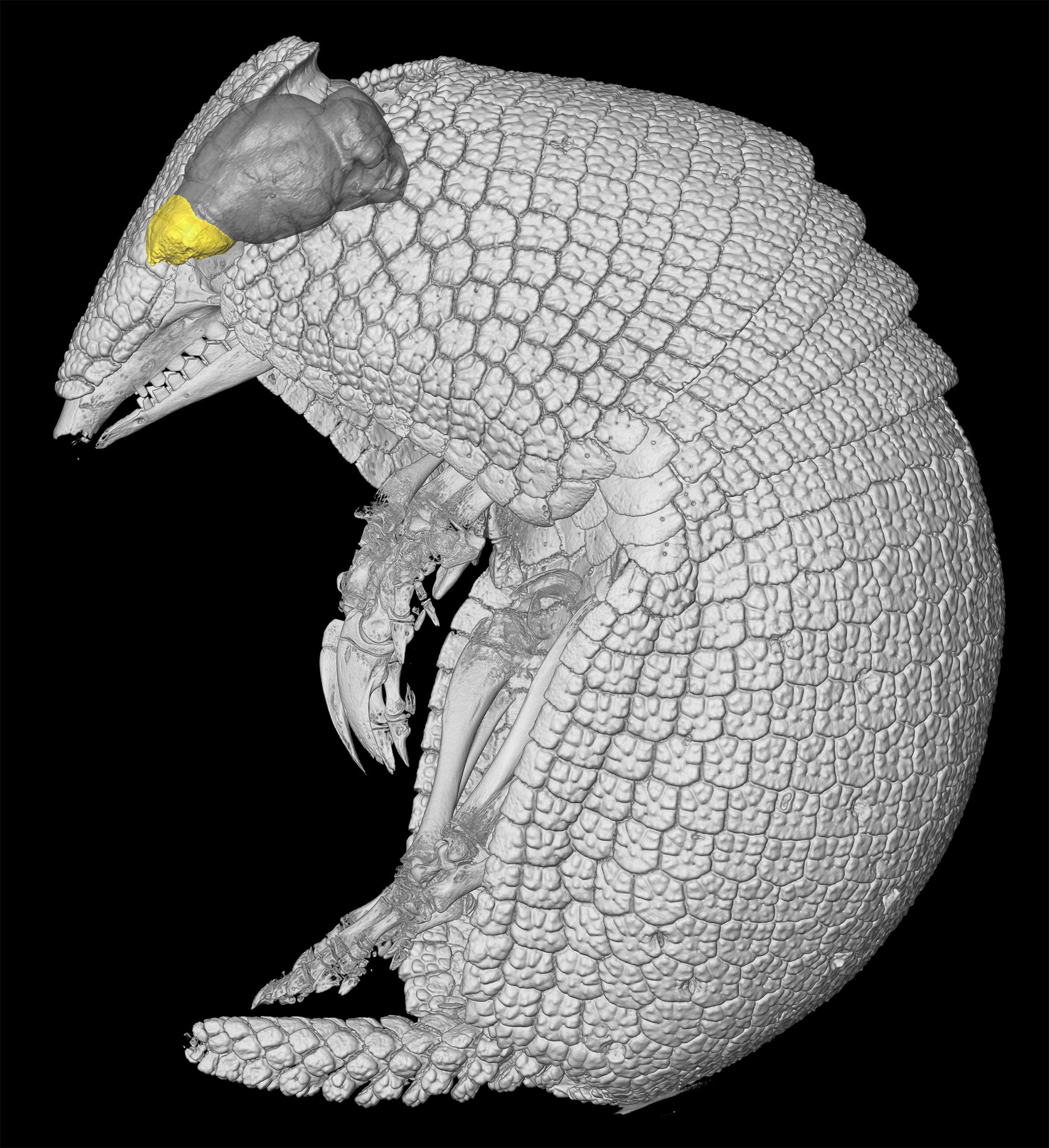

To test whether olfactory bulb size reflects genetic investment in smell, the team created three-dimensional brain endocasts from 71 mammal species. Sixty-six were living mammals, spanning every mammalian order. The rest were iconic extinct species, including the saber-toothed cat, early whales, and the Tasmanian tiger.

Some skulls came from museum collections and were scanned using high-resolution CT machines. Others were sourced from online databases. The scans captured fine internal details, allowing researchers to digitally reconstruct the brain cavity.

Separating the olfactory bulb from the rest of the brain was not always easy. In some animals, a clear groove marks the boundary. In others, the transition is gradual. Species with very small bulbs posed special challenges. To reduce bias, one operator applied the same rules to all specimens.

Because mammals range from tiny shrews to massive elephants, raw bulb size alone was not useful. Larger animals naturally have larger brains. The researchers corrected for body size using the width of the occipital condyles, where the skull meets the spine. This produced a size-adjusted measure called relative olfactory bulb volume.

Next, the team compared anatomy with genetics. They gathered published counts of intact chemoreceptor genes for each species. These genes encode receptors that detect smells and tastes. The focus was on classic olfactory receptor genes, which make up most of the smell-related genome.

They also considered other receptor families, including vomeronasal receptors and taste receptors. Combined measures were created to reflect overall chemosensory capacity.

Statistical tests revealed a strong pattern. Relative olfactory bulb volume closely tracked the number of olfactory receptor genes. More than half of the variation in bulb size could be explained by gene count alone. Measures that combined several smell-related gene families showed similar results.

Absolute bulb size, by contrast, mostly reflected body size. It was a poor predictor of genetic investment in smell.

Not all receptor genes showed the same relationship. Taste receptors and some pheromone-related receptors correlated weakly or not at all with bulb size. That makes sense biologically.

Classic olfactory receptors dominate the system and send signals directly to the main olfactory bulb. Other receptors use different brain pathways or play smaller roles. Changes in those genes are less likely to reshape overall bulb volume.

These findings suggest that the olfactory bulb endocast mainly reflects the primary smell system, not every aspect of chemical sensing.

Clear ecological patterns emerged. Aquatic and semi-aquatic mammals, including dolphins, whales, seals, and manatees, had some of the smallest relative olfactory bulbs and fewest smell genes. One dolphin species lacked a recognizable bulb altogether.

Primates also tended to score low. Many monkeys showed reduced bulb size and gene counts, matching long-standing ideas that vision replaced smell as a dominant sense in primate evolution.

At the other extreme stood the African elephant. It ranked among the highest for both bulb size and smell genes. The result supports observations that elephants rely heavily on scent for social life, navigation, and foraging.

Some species did not fit neatly. The echidna showed very high gene counts but only moderate bulb size. Such mismatches suggest that neuron density, development, and skull constraints also shape olfactory systems.

“The most powerful outcome of our study is its application to fossils. Using the link between bulb size and gene number, we estimated smell capacity in extinct species that left no DNA,” Martinez shared with The Brighter Side of News.

The saber-toothed cat showed a smaller relative bulb than wolves, suggesting a weaker sense of smell than modern canids. The estimate matched earlier work based on other skull features.

Early whales told a different story. Fossils from the Eocene showed a clear olfactory bulb, larger than those of modern whales. “This suggests that they had a good sense of smell,” Martinez said. “Early whales from the Eocene therefore probably had a very good sense of smell.” Over time, as whales adapted fully to aquatic life, that ability faded.

The Tasmanian tiger produced a surprise. Its bulb size ranked among the largest in the dataset. Genetic data suggest fewer smell genes than expected, likely due to incomplete genomes. In this case, skull anatomy may be the better guide.

By linking bone to genes, the study offers a reliable method to explore smell in deep time. It shows that the relative size of the olfactory bulb preserves a record of sensory evolution across habitats and lifestyles.

As more genomes are sequenced and more fossils are scanned, this approach will sharpen. It promises new insights into how mammals once navigated their worlds, guided by scents that vanished long ago.

This research gives scientists a powerful new tool to study behavior and ecology in extinct animals. By estimating smell ability from skulls, researchers can better infer diet, habitat, and social behavior in species known only from fossils.

The method also strengthens links between anatomy and genetics in living mammals, helping biologists understand how senses evolve.

In the future, it may guide conservation work by clarifying how sensory loss or specialization affects survival in changing environments.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Fossil skulls reveal how well extinct mammals could smell appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.