Neurons never sit still for long. Receptors move in and out of the cell surface. Signals surge, fade, then surge again. Beneath that activity, a fine lattice made of actin and spectrin quietly lines the inner membrane.

In a new study, researchers used super-resolution imaging to watch how that lattice, known as the membrane-associated periodic skeleton, or MPS, shapes what enters a neuron and what stays out. Their findings suggest the MPS does more than hold structure. It acts as a physical barrier that regulates endocytosis, the process cells use to pull material inside.

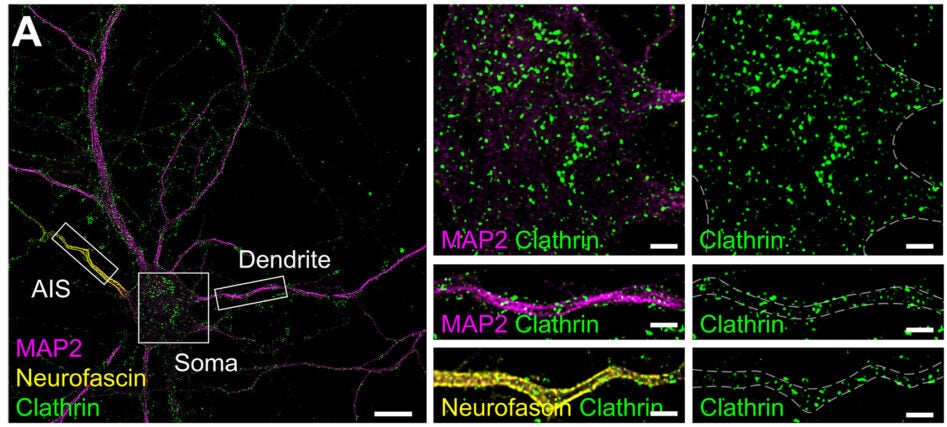

The team visualized four major endocytic pathways in mature neurons: clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, flotillin-mediated endocytosis, and fast endophilin-mediated endocytosis. Using structured illumination microscopy and 3D STORM imaging, they mapped where these pathways operate across axons, dendrites, and the axon initial segment.

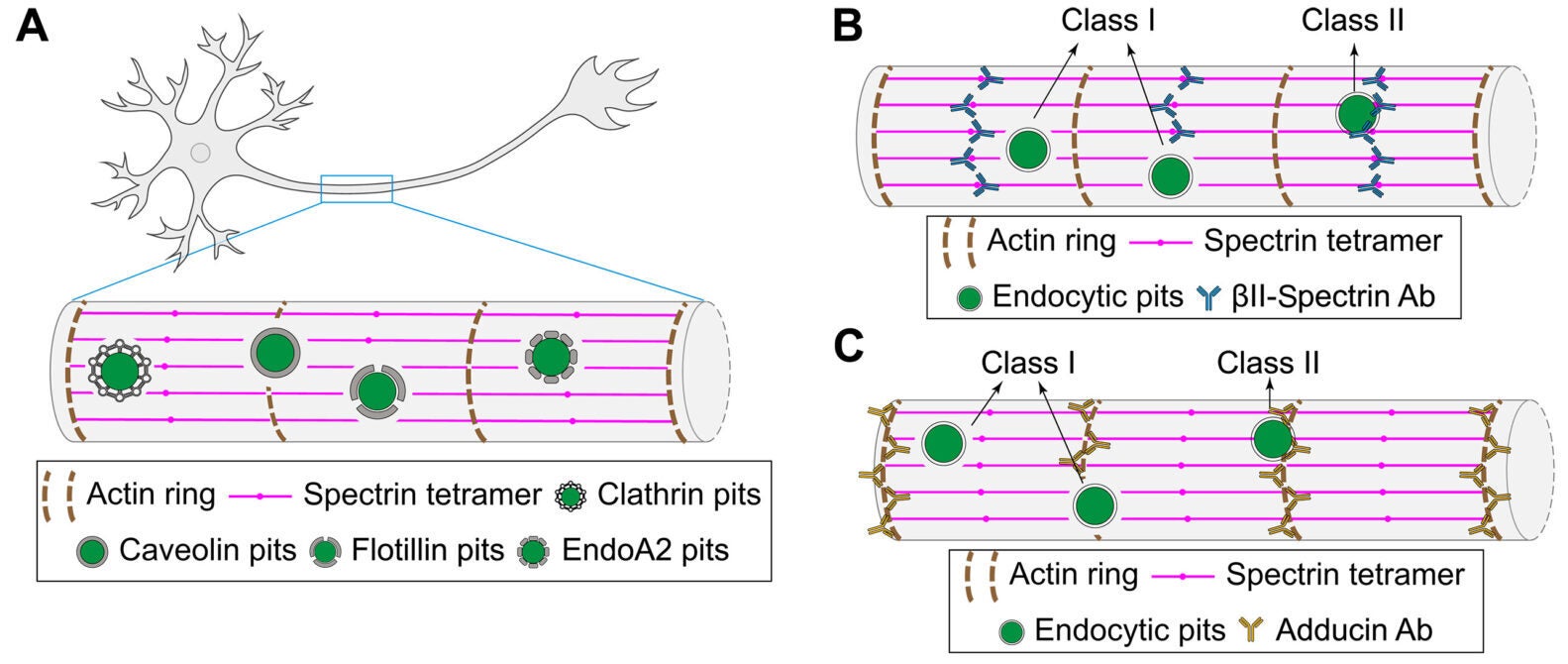

The MPS forms a repeating, ring-like scaffold beneath the membrane, spaced about 190 nanometers apart in neurites. Earlier work had hinted that clathrin-coated pits gather in gaps within this lattice at the axon initial segment. This study extended that idea.

Across axons and dendrites, most endocytic pits sat in circular “clearings” where the MPS signal dropped away. When researchers classified pits by whether they overlapped with the lattice, the majority fell into the nonoverlapping category. Pearson’s correlation analysis confirmed that the spatial separation was not random.

Clathrin pits averaged about 82 nanometers in diameter. Caveolin pits averaged about 75 nanometers. Flotillin and endophilin pits were slightly smaller, around 72 and 67 nanometers. Regardless of size or pathway, they preferred the same kind of clearing.

It was not limited to axons. In mature neurons, dendrites showed the same pattern. The absence of clearings in earlier reports likely reflected immature cultures in which the dendritic MPS had not fully formed.

To test whether the lattice actually restrains uptake, the team disrupted the MPS by knocking down βII-spectrin. In mature neurons, this reduced βII-spectrin levels by about 70 percent.

Endocytic pit density rose in all compartments. Clathrin, caveolin, flotillin, and endophilin pits all increased when the lattice weakened. In immature neurons, where the dendritic MPS is not yet established, disrupting βII-spectrin did not boost pit density. That contrast suggests the effect depends on the scaffold itself.

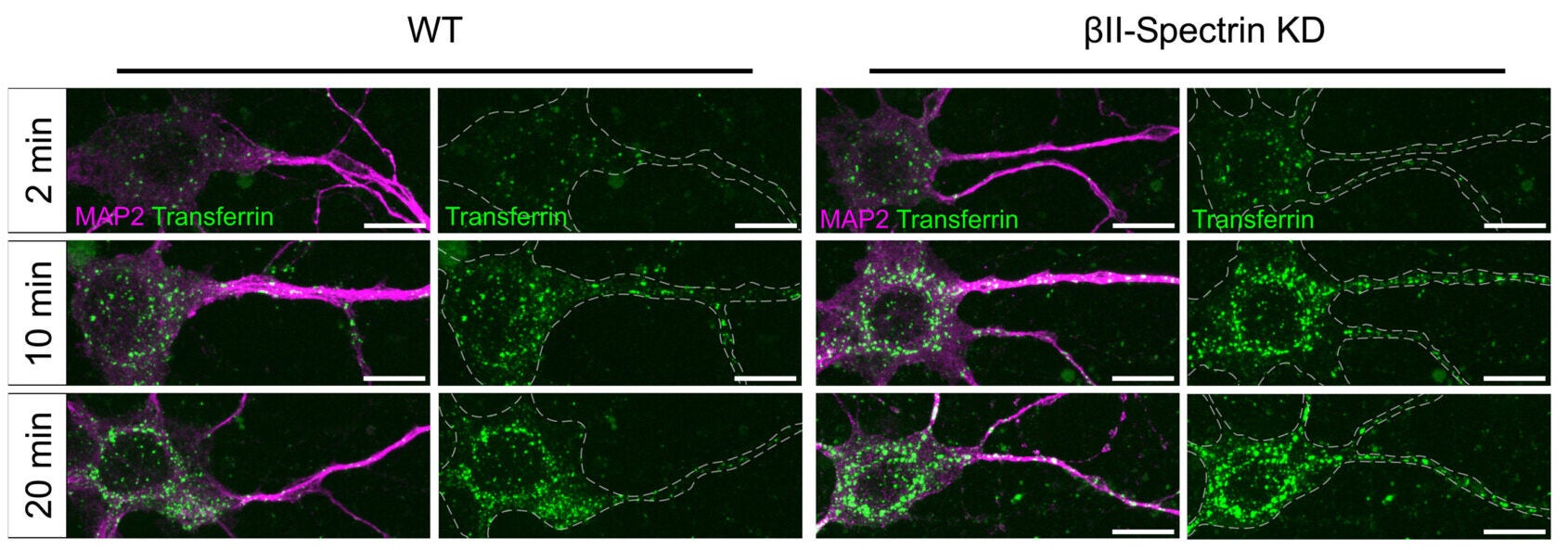

Ligand-induced uptake told a similar story.

Transferrin and low-density lipoprotein, which enter through clathrin-mediated pathways, were internalized faster in MPS-disrupted neurons. Transferrin uptake showed a time constant of 8.29 minutes in βII-spectrin knockdown cells, compared with 17.15 minutes in controls. LDL uptake dropped from 54.63 minutes in controls to 35.25 minutes after knockdown.

For caveolin-mediated uptake, the team tracked antibody-triggered internalization of HA-mGluR5a. The time constant fell from 37.77 minutes in control neurons to 9.18 minutes when the MPS was disrupted.

Endophilin-mediated uptake of NCAM1 also increased in both axons and dendrites after MPS disruption.

The scaffold appears to function as a physical brake. Remove it, and receptors move inward more quickly.

The story does not stop at mechanical restraint. Endocytosis itself fed back on the scaffold.

Ligand stimulation of transferrin receptor, HA-mGluR5a, or NCAM1 triggered sustained ERK activation. Blocking endocytosis reduced ERK signaling, indicating that internalized receptors contribute to that pathway.

ERK activation coincided with degradation of the MPS. Using autocorrelation analysis of spectrin organization, the team measured reduced lattice integrity after ligand stimulation. Inhibiting ERK with U0126 prevented this degradation. So did blocking endocytosis with dyngo-4a.

Protease inhibitors added another layer. Calpain inhibition with MDL-28170 and caspase inhibition with Z-VAD-FMK both preserved spectrin structure. Western blot analysis showed spectrin cleavage fragments consistent primarily with calpain activity.

When the lattice degraded, endocytosis accelerated further. Preventing degradation slowed ligand-induced uptake. The data support a positive feedback loop: endocytosis activates ERK, ERK activates proteases, proteases cleave spectrin, and the weakened scaffold permits more endocytosis.

It is a system that can ramp up quickly when needed.

The researchers then turned to amyloid precursor protein, or APP. Pathogenic Aβ42 peptide forms after APP is internalized and processed in endosomes and lysosomes.

Using a superecliptic pHluorin-tagged APP construct, they found that APP uptake occurred faster in βII-spectrin knockdown neurons. The time constant dropped from 37.21 minutes in controls to 14.52 minutes after MPS disruption.

In neurons overexpressing APP695, either wild-type or the Swedish mutation variant, intracellular Aβ42 levels increased. When the MPS was disrupted, Aβ42 accumulation rose further. Without APP overexpression, βII-spectrin knockdown did not raise Aβ42 levels.

Cleaved caspase-3, a marker of apoptosis, followed a similar pattern. APP overexpression increased caspase-3 activation, and MPS disruption amplified it.

The lattice appears to limit APP internalization and downstream Aβ42 production. When the scaffold weakens, uptake accelerates, and pathogenic processing rises.

This work positions the MPS as more than a structural support. It acts as a dynamic regulator of membrane trafficking. By constraining both basal and ligand-driven endocytosis, it helps neurons control signaling intensity and duration.

The positive feedback loop linking endocytosis, ERK activation, and spectrin cleavage may allow rapid responses to stimulation. At the same time, it creates vulnerability. If the scaffold destabilizes during aging or stress, receptor uptake could spiral upward.

In the context of Alzheimer’s disease, preserving MPS integrity might reduce excessive APP internalization and Aβ42 accumulation. Calpain and caspase pathways, already implicated in neurodegeneration, intersect directly with this structural system.

Understanding how to stabilize the MPS, or how to interrupt the feedback loop without blocking necessary signaling, could open new directions for therapeutic strategies.

The neuron’s inner scaffold, once viewed as static support, now looks like a gatekeeper.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

The original story “‘Gatekeeper’ lining brain cells may guard against Alzheimer’s disease” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post ‘Gatekeeper’ lining brain cells may guard against Alzheimer’s disease appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.