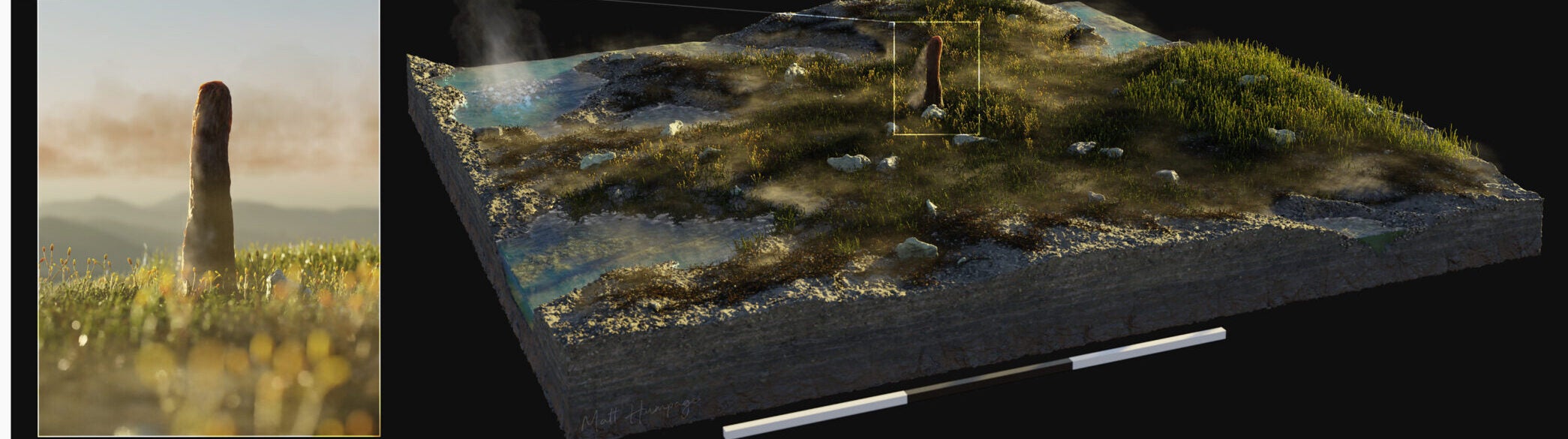

Over 150 years ago, a fossilized organism known as Prototaxites emerged as an enigma regarding what early land life may have been like. As an organism that appeared to grow up through Earth’s crust in the form of a large column (or pillar) between 420 and 370 million years ago, Prototaxites was one of the largest terrestrial (land) organisms of its time. Some samples reached an estimated height of 8 m (25 ft) in length.

Characteristics of Prototaxites include the absence of flowers, leaves, stems, and root systems. Instead, their structure consisted of smooth, pillar-like trunks that were likely anchored into the soil through a swollen root base.

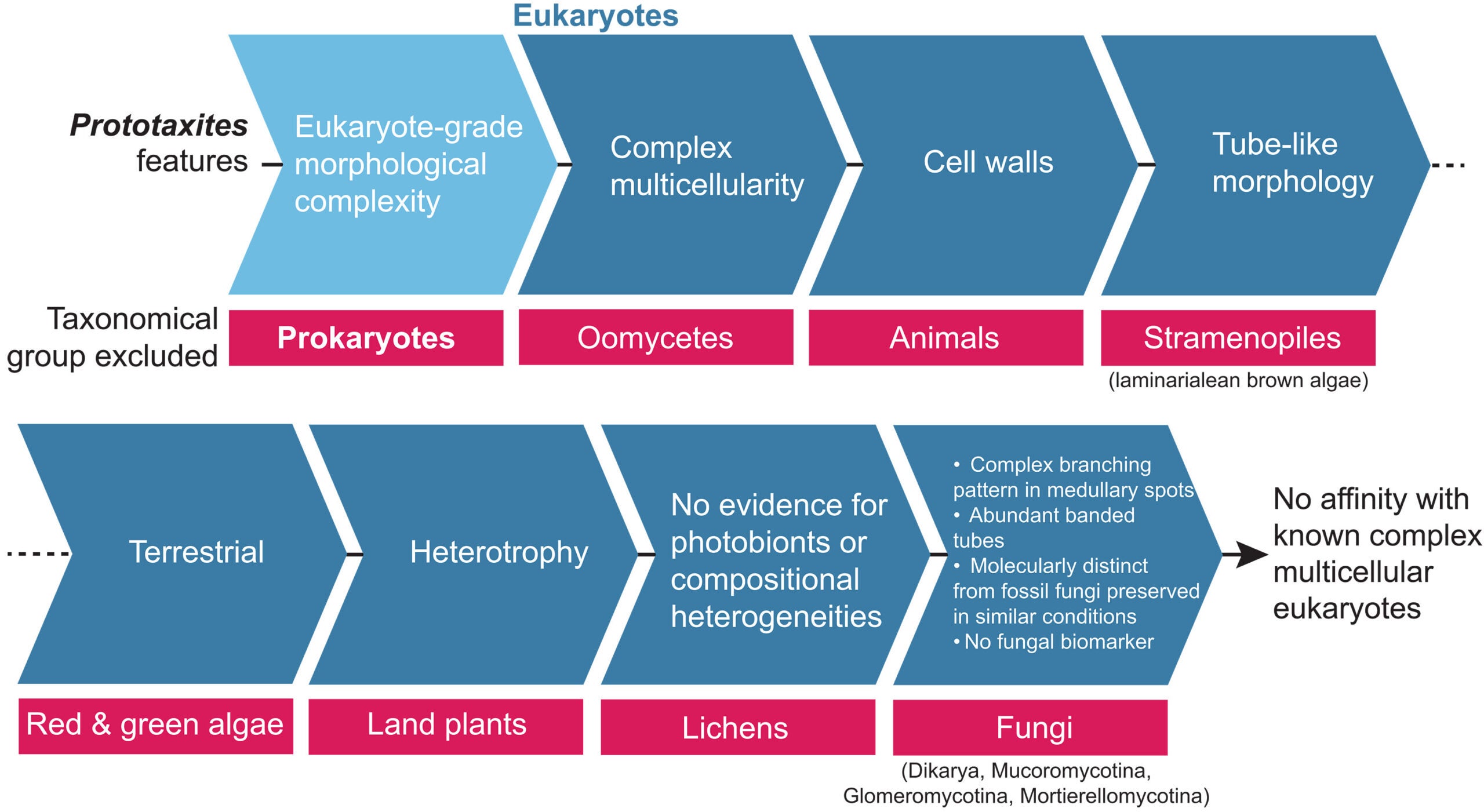

Since Prototaxites was discovered in the mid-1800s, there has been disagreement among scientists regarding what type of organism this was. Some proposed it was a large fungus. Others suggested a type of algae or plant, while others believed it was a lichen-like mutualism between two different types of organisms. New findings from researchers affiliated with several universities now suggest that Prototaxites is a member of a previously unknown and now-extinct line of complex organisms.

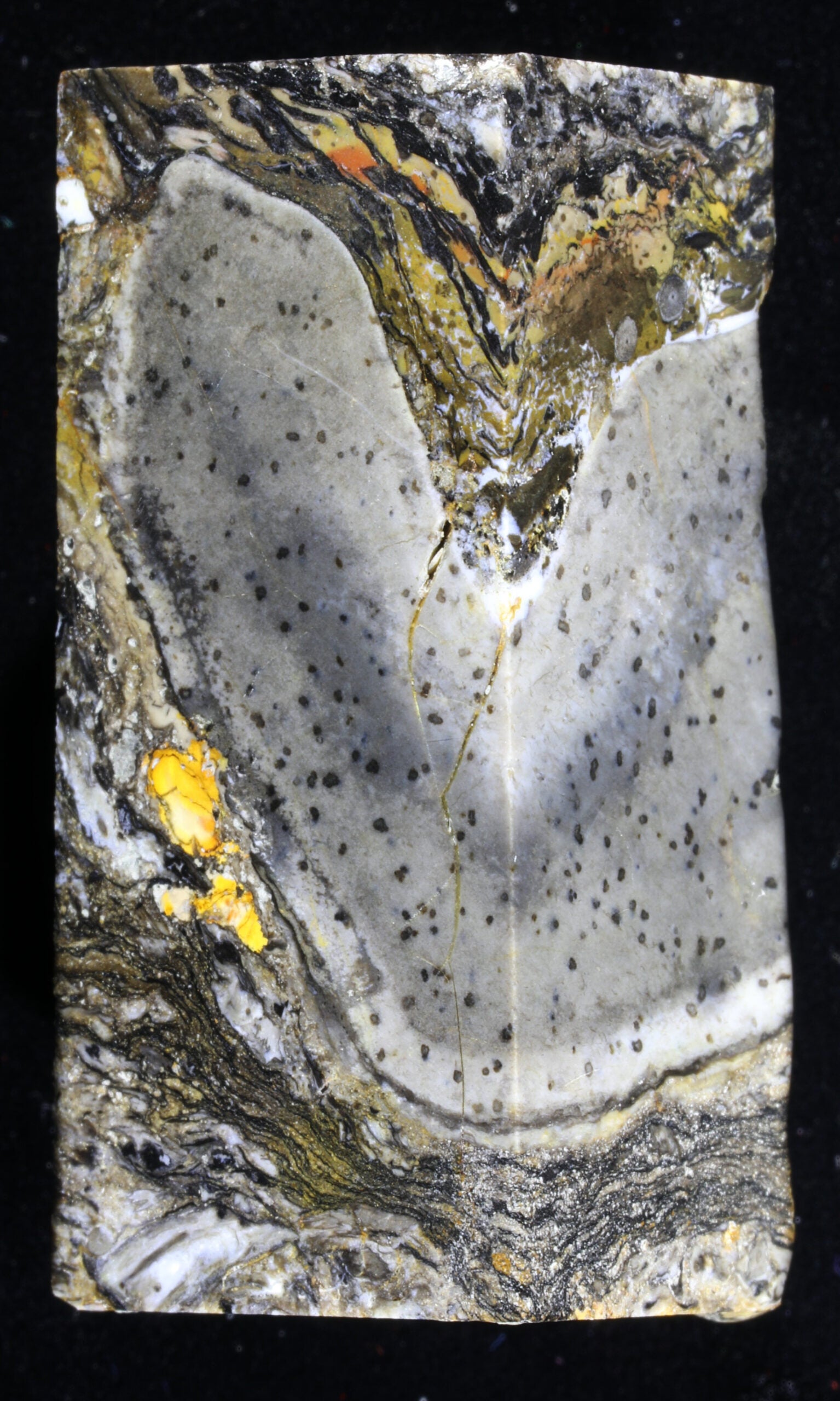

New information on Prototaxites taiti, based on fossils found in the Rhynie Chert in northeastern Scotland, supports this current belief about Prototaxites. This particular fossil site is famous to paleontologists for the preservation of a broad range of early life forms that lived simultaneously with each other, including animals, plants, fungi, and some of the earliest complex multicellular organisms. Thus, this unique site provides a great deal of comparative data for scientists studying eukaryotic organisms in general.

One focus of the new investigations of Prototaxites taiti is a specimen identified as NSC.36, which was found to be both larger and better preserved than any other previously identified sample of P. taiti. The sample left behind contains various types of material that allow for detailed chemical and imaging analysis.

The type of material preserved was common between Prototaxites and other fossilized fungi, allowing comparisons to be made. This eliminated problems found in previous studies in which differences could be attributed to the process of fossilization rather than biological differences.

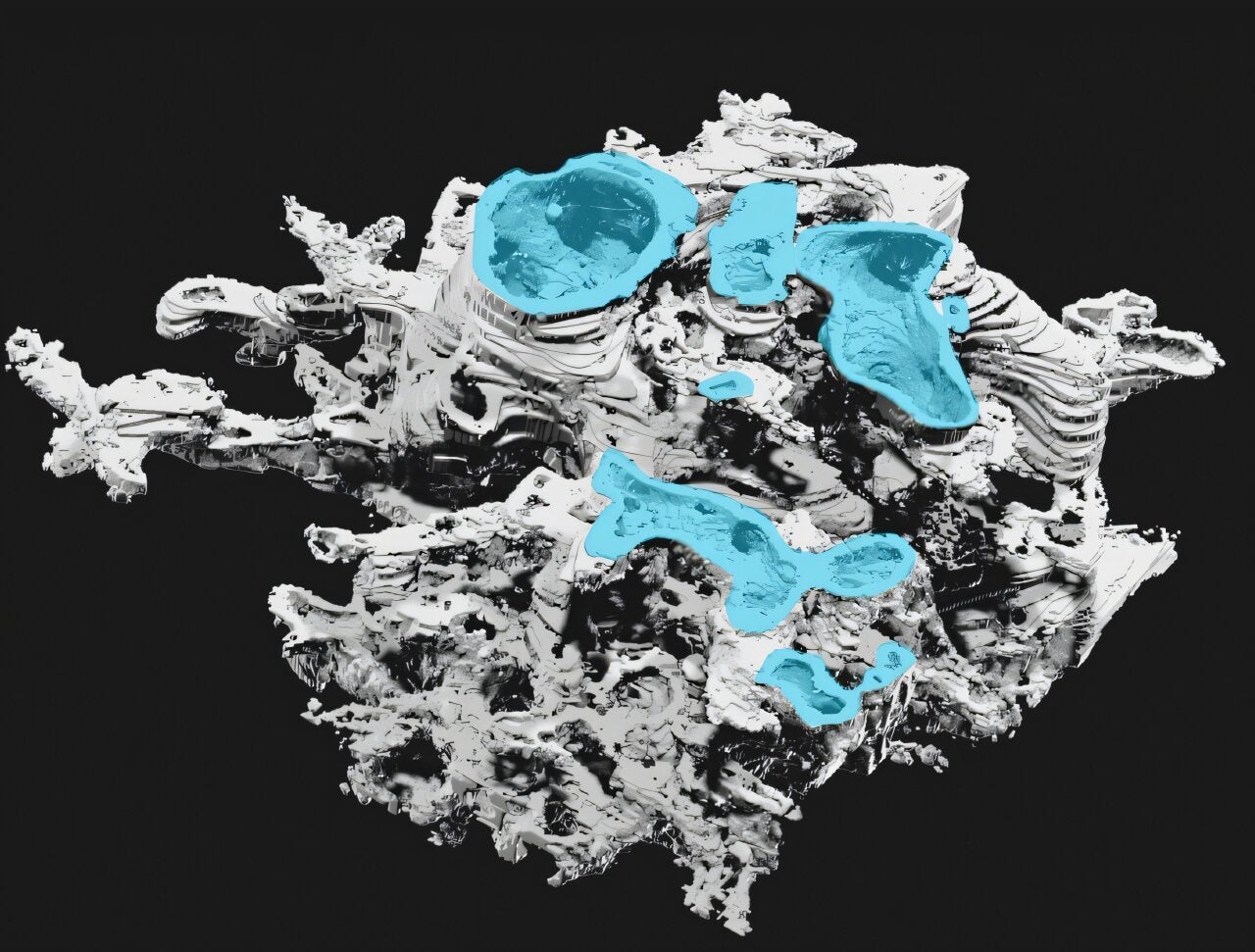

Scientists examined the fossil of NSC.36 using laser scanning microscopy, 3D re-sampling, and other methodologies involving confocal laser scanning microscopy. They discovered that NSC.36 had developed a dense network of tubes. However, these were not normal fungal tubes.

Normal fungal growth is achieved through the formation of hyphae. These hyphae have a predictable branching pattern. Prototaxites taiti, however, had a three-way branching pattern. The tubes formed denser hubs called medullary spots, in which many tubes of various types connected to one another in more complex, three-dimensional patterns.

“In the books and books of anatomy written about living fungi, we never find structures like that,” University of Edinburgh paleobotanist and study co-lead Alexander Hetherington said.

“The structure of the Prototaxites tube system displayed the same type of biological exchange systems as blood capillaries and lungs, which are composed of tubes strategically arranged to efficiently transfer resources within a living organism. To date, no known fungi are capable of creating tissues in this manner,” he told The Brighter Side of News.

“Our team also identified larger tubes developing laminae around them and having a circular shape. Previously, similar banding had only been found on the reproductive portions of some living fungi. However, large tubes with laminae were identified externally throughout the entire Prototaxites body and have a striking resemblance to the thicker, water-conducting cells of plant life that provide support and transport in an organism’s body,” he added.

These features, however, are not considered a hallmark of fungi. Although the fossils were well preserved, the researchers did not find any reproductive structures (spores) or any photosynthetic partners associated with the fossils. Nor did they observe any evidence of a mutualistic lichen-like relationship (symbiosis).

The researchers were unable to reach a conclusion regarding whether the fossils could be classified as fungi based on fossil anatomy alone. As a result, they conducted additional analyses of the chemical signature (chemical fingerprint) of the fossils using infrared spectroscopy and artificial intelligence and machine learning models.

Fungi produce chitin in their cell walls, which is also produced in the shells of arthropods (insects, spiders, etc.) and can be preserved in fossil form. The researchers examined fossilized Prototaxites based on their chemical profiles and compared them to the chemical profiles of known chitin-producing groups. These included fossils of arthropods, plants, bacteria, and all other organisms preserved in the fossil deposit along with Prototaxites fossils.

The comparison of chemical profiles produced through infrared spectroscopy resulted in major differences between Prototaxites and all other chitin-producing organisms, including fungi.

Using statistical models, the researchers successfully differentiated Prototaxites from all known fungal taxa and achieved over 90 percent accuracy rates and high discrimination scores between Prototaxites and all chitin-producing taxa.

In order to confirm their initial findings, the researchers also directly extracted organic material from the fossil. The chemical signatures of the cell walls of Prototaxites were uniquely different from the chemical signatures of fungi. These fungal signatures were easily identified in surrounding materials containing remnants of fungal tissues, confirming the efficacy of the methods used to analyze the fossils.

An argument concerning the identification of Prototaxites taiti centers on a pigment compound, or byproduct, called perylene. This compound is recognized as a marker for various ascomycete fungi present in the Rhynie Chert.

Recent work has tested the previously hypothesized relationship between ascomycetes and Prototaxites taiti through direct analysis. In this analysis, perylene was identified in the plant-ridden substrate surrounding Prototaxites. However, it was not identified in any pure Prototaxites samples. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the ascomycete hypothesis has been significantly weakened, and it joins the growing list of mismatching evidence for ascomycete-clade fungi.

The authors of this study also address inconsistencies and disagreements with the results of previous chemical studies. They argue that using chemical ratios alone does not suffice when categorizing fossil organisms. Instead, they advocate for working with the entire fossil assemblage, as opposed to focusing solely on individual fossils through comparative analysis.

The authors took a bold step in their interpretation of these lines of evidence and emphasize that their comprehensive analysis leads them to question the classification of Prototaxites taiti as a member of the ascomycete group and part of the fungal crown group. Instead, they assert that Prototaxites should be classified as belonging to an undescribed lineage of extinct eukaryotes.

In essence, Prototaxites represents a massive branch of the broader eukaryotic lineage that no longer exists. This organism was likely a land-based heterotroph that consumed organic matter and would have played an important role in supporting the ecology of early land-based ecosystems. Fossils of arthropods indicate that they fed on Prototaxites.

If the authors’ interpretation proves valid, this category of fossil will remind researchers of the highly experimental relationships that existed among the many types of life on Earth at the start of its terrestrial ecosystem era. Consequently, many different branches of complex life forms may have developed, proliferated, and perished, leaving behind only puzzling fossil remnants.

As a result of this research effort, current understanding of the early evolutionary history of complex terrestrial life has shifted. Prototaxites taiti’s classification as an extinct lineage offers insight into the existence of other forms of plant, fungal, and animal life, collectively comprising only a fraction of what has existed on the planet. In addition, this information will provide guidance for future searches for fossil organisms, preventing researchers from incorrectly categorizing ancient organisms into contemporary categories.

The results of this study also highlight the power of integrating imaging, chemical analyses, and artificial intelligence in paleontology. By utilizing these three tools in conjunction with one another, paleontologists can recover biological data previously thought lost and develop models of the conditions that resulted in maintaining the current nature of biodiversity on the planet.

The application of this integrative research approach may, over time, lead to the discovery of other lost branches of life and inform how current biodiversity has been maintained and improved upon.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Giant Prototaxites fossil reveals an extinct branch of complex life on Earth appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.