Glaciers around the world are shrinking at a pace scientists say will continue for decades. Public attention often focuses on rising seas and water shortages. Another part of the story has received far less notice: the rapid loss in the number of glaciers themselves. More than 200,000 glaciers appear in global inventories today. Many of them could vanish within your lifetime.

For communities living near ice, this loss feels deeply personal. Glaciers attract millions of visitors each year and support ski resorts and local jobs. They also carry cultural, spiritual, and historical meaning. In Iceland, Switzerland, and Nepal, people have held symbolic funerals for dying glaciers. Iceland has even created a global glacier graveyard to honor what has already vanished.

Efforts such as the Global Glacier Casualty List aim to preserve glacier names and stories. These projects reflect a growing recognition that glacier loss is not just a scientific measurement. It is also an emotional and cultural rupture.

A new international study offers a clearer way to understand how fast this loss will unfold.

An international research team led by ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, and Vrije Universiteit Brussel examined when individual glaciers will disappear entirely. The study was published in Nature Climate Change. Instead of focusing only on shrinking ice mass or surface area, the team tracked glacier-by-glacier disappearance.

“For the first time, we’ve put years on when every single glacier on Earth will disappear,” said Lander Van Tricht, the study’s lead author and a researcher at ETH Zurich’s Chair of Glaciology and WSL.

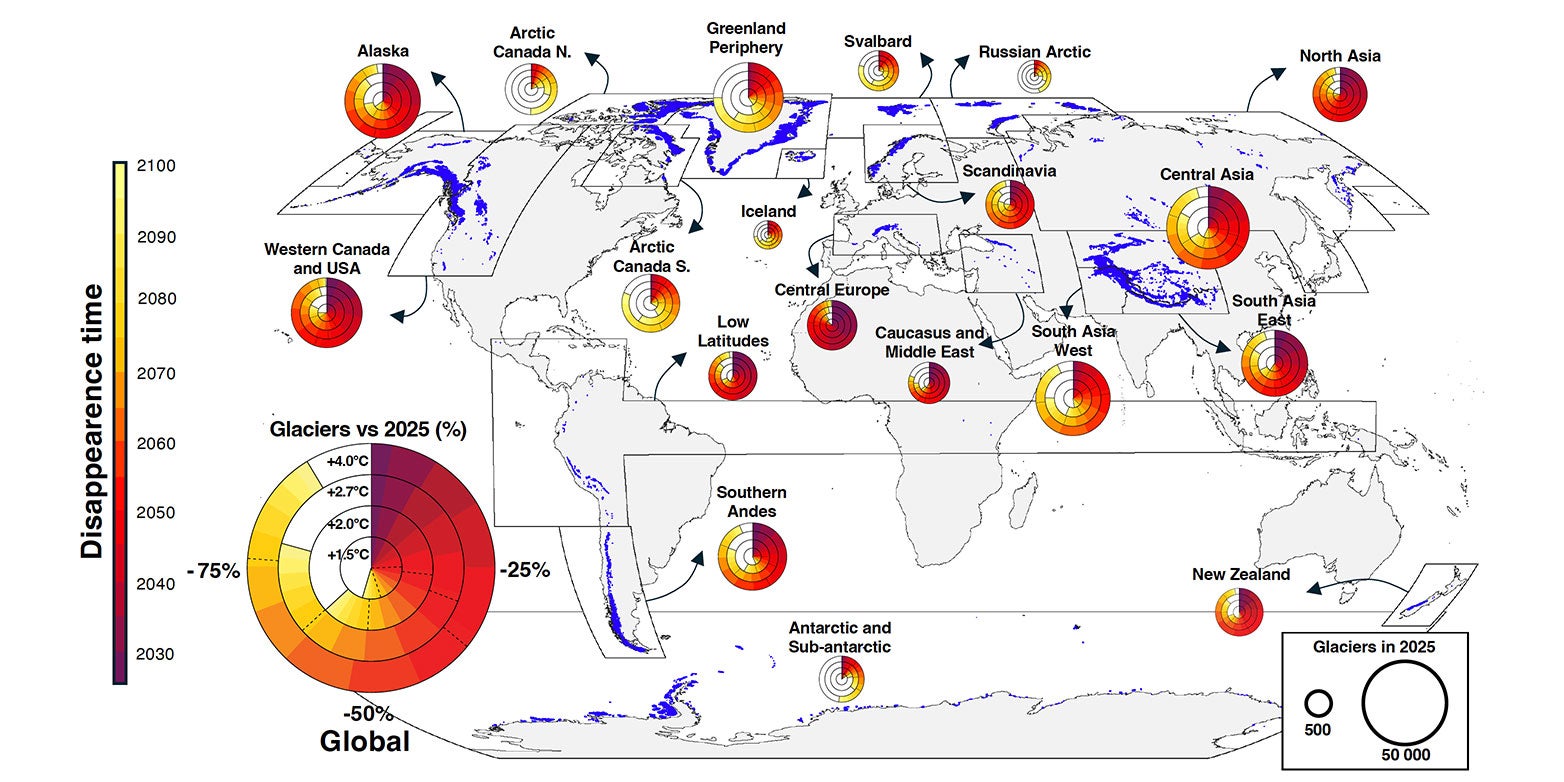

The researchers ran projections using three state-of-the-art global glacier models. They examined four warming scenarios. These included 1.5°C and 2.0°C, which align with international climate goals; 2.7°C, which reflects current policy pledges; and a high-emissions path of 4.0°C.

A glacier counted as “disappeared” once its area dropped below 0.01 square kilometers or its ice volume fell under 1 percent of its original size. Using this definition, the team introduced a new concept called “Peak Glacier Extinction.” This marks the year when the most glaciers vanish worldwide within a single year.

The timing of peak glacier extinction depends on how much the planet warms. Under a 1.5°C scenario, the global peak arrives around 2041. About 2,000 glaciers would disappear in that single year. Under 4.0°C, the peak shifts to the mid-2050s and rises to roughly 4,000 glaciers per year.

At first glance, the later peak under stronger warming seems odd. The explanation lies in glacier size. Under moderate warming, mostly small glaciers vanish quickly. Under extreme warming, even the largest glaciers collapse, pushing the peak later and higher.

“Every tenth of a degree counts in slowing the decline,” said Daniel Farinotti, a study co-author and professor of glaciology at ETH Zurich. “The results underline how urgently ambitious climate action is needed.”

Today, about 750 to 800 glaciers disappear each year. At peak levels, that rate could triple or even quintuple. Even after the peak passes, glacier loss does not stop. Late in the century, between 700 and 1,200 glaciers per year could still vanish.

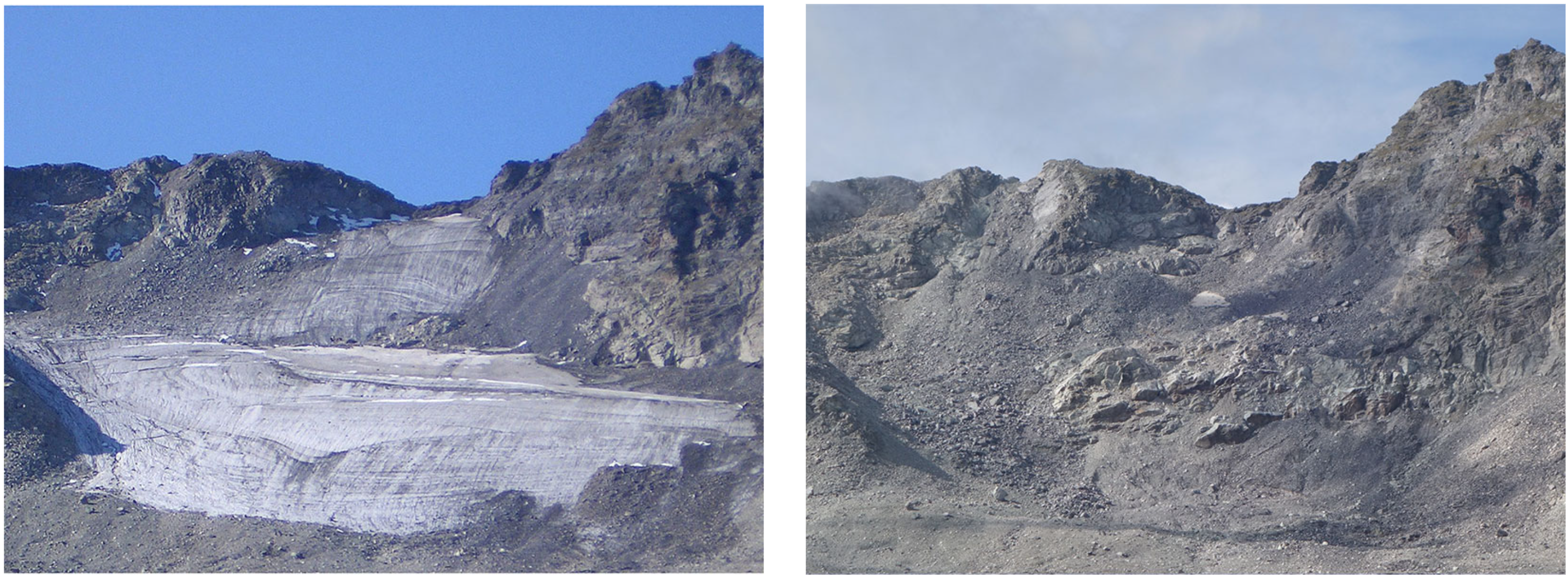

The study shows strong regional differences. Areas dominated by small glaciers will see losses sooner and faster. The Alps, the Caucasus, the Subtropical Andes, North Asia, and the Rocky Mountains fall into this category. In these regions, more than half of all glaciers may disappear within the next 10 to 20 years.

“In these regions, more than half of all glaciers are expected to vanish within the next ten to twenty years,” Van Tricht said.

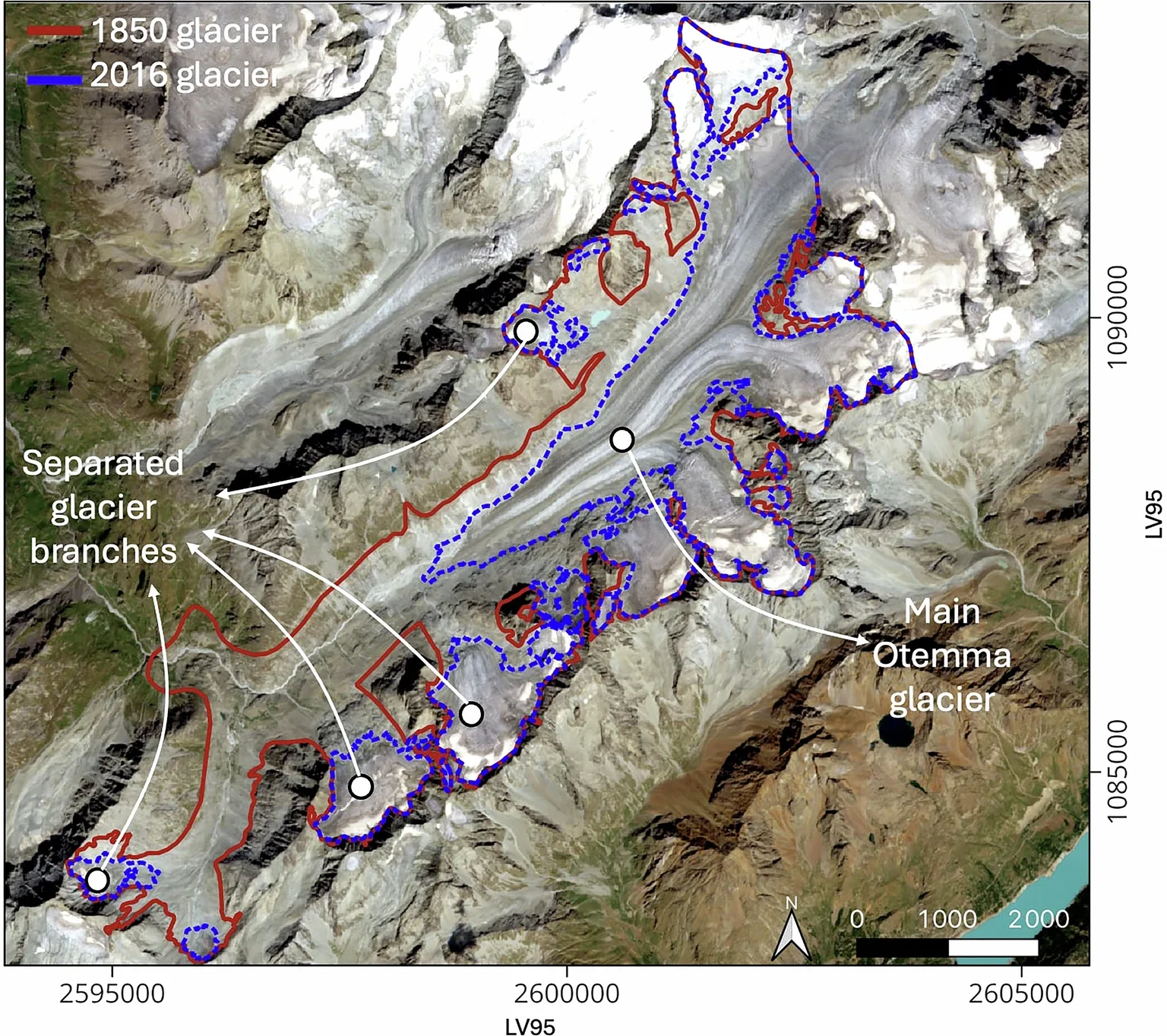

In Central Europe, peak glacier loss could arrive as early as 2033 to 2041. ETH Zurich researchers previously showed that more than 1,000 glaciers vanished in Switzerland alone between 1973 and 2016, as reported in Annals of Glaciology. The new projections suggest the trend will continue.

Larger glacier regions behave differently. Greenland’s peripheral glaciers, Svalbard, the Russian Arctic, and parts of High-Mountain Asia reach peak loss later. These glaciers respond more slowly because of their size. In Canada’s High Arctic, some areas may not reach peak glacier extinction until after 2100.

“The survival of glaciers depends heavily on warming levels. Under a 1.5°C scenario, we believe that nearly half of today’s glaciers could remain by 2100. Under current policy pledges, which place the world near 2.7°C, only about 20 percent are likely to survive,” Van Tricht explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Under 4.0°C, the picture becomes far bleaker. Between 2035 and 2065, the planet could lose 3,000 to 4,000 glaciers each year with fewer than 10 percent of today’s glaciers remaining by century’s end,” he concluded.

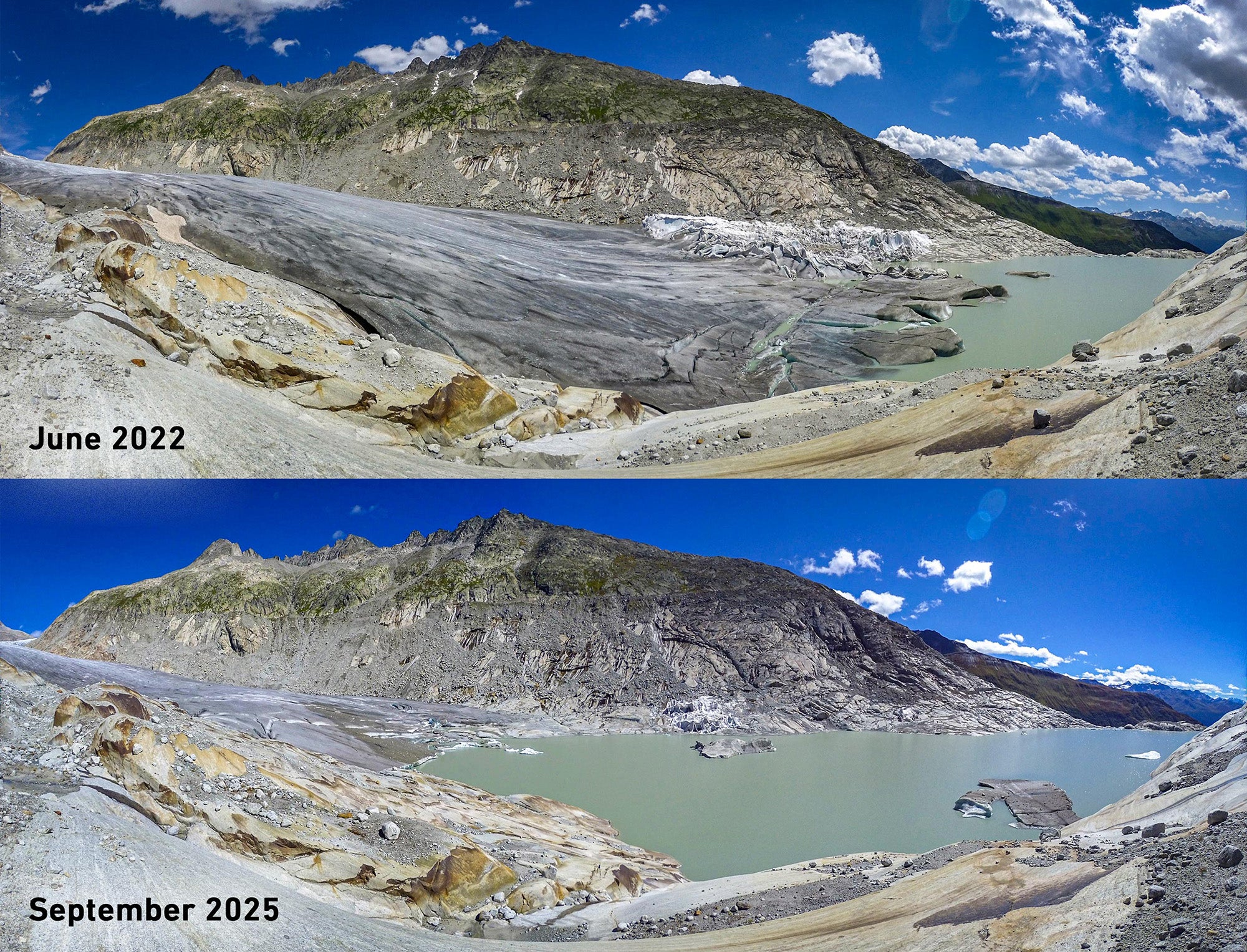

The Alps offer a stark example. At 1.5°C, about 430 glaciers may survive by 2100, roughly 12 percent of today’s total. At 2.0°C, that number drops to about 270. At 4.0°C, only around 20 glaciers would remain. Even famous ice bodies such as the Rhône Glacier would shrink to small remnants. The Aletsch Glacier could fragment into several pieces.

Similar losses appear elsewhere. In the Rocky Mountains, about 25 percent of glaciers may survive at 1.5°C. At 4.0°C, that number falls to about 1 percent. In the Andes and Central Asia, roughly 43 percent could survive at 1.5°C, but more than 90 percent would vanish at 4.0°C.

No region escapes decline. Even the Karakoram, where some glaciers briefly grew after 2000, shows long-term losses in the projections.

The disappearance of glaciers reshapes more than landscapes. “The melting of a small glacier hardly contributes to rising seas,” Van Tricht said. “But when a glacier disappears completely, it can severely impact tourism in a valley.”

The new approach offers tools for policymakers, tourism planners, and hazard managers. Knowing when and where glaciers vanish helps communities prepare for reduced water supplies, changing landscapes, and economic shifts.

Researchers involved in the study also support efforts like the Global Glacier Casualty List. “Every glacier is tied to a place, a story and people who feel its loss,” Van Tricht said. “That’s why we work both to protect the glaciers that remain and to keep alive the memory of those that are gone.”

With 2025 named the International Year of Glacier Preservation, the study highlights a clear message. The world’s choices in the coming years will shape whether peak loss reaches 2,000 glaciers per year or doubles to 4,000. The timeline is not fixed. The outcome still depends on action.

The findings help governments and communities plan for a future with less ice. Tourism regions can prepare for glacier loss that may affect local economies. Water managers can anticipate long-term changes in seasonal meltwater. Cultural groups gain tools to document and preserve glacier heritage before it disappears.

For science, the study provides a new way to communicate climate impacts in human terms. Tracking glacier disappearance, not just ice mass, makes climate change more tangible. For society, the work reinforces a simple truth: limiting warming directly saves glaciers, landscapes, and the histories tied to them.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Glaciers are disappearing faster than ever, and scientists now know when the loss will peak appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.