Light can tell you a lot about what matter is doing. Visible light shows a surface. X-rays reveal hidden structure. Infrared picks up heat.

Now researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found a way to use terahertz light to watch a superconductor move in a new way. The work, led by MIT physicist Nuh Gedik and MIT postdoc Alexander von Hoegen, appears in the journal Nature.

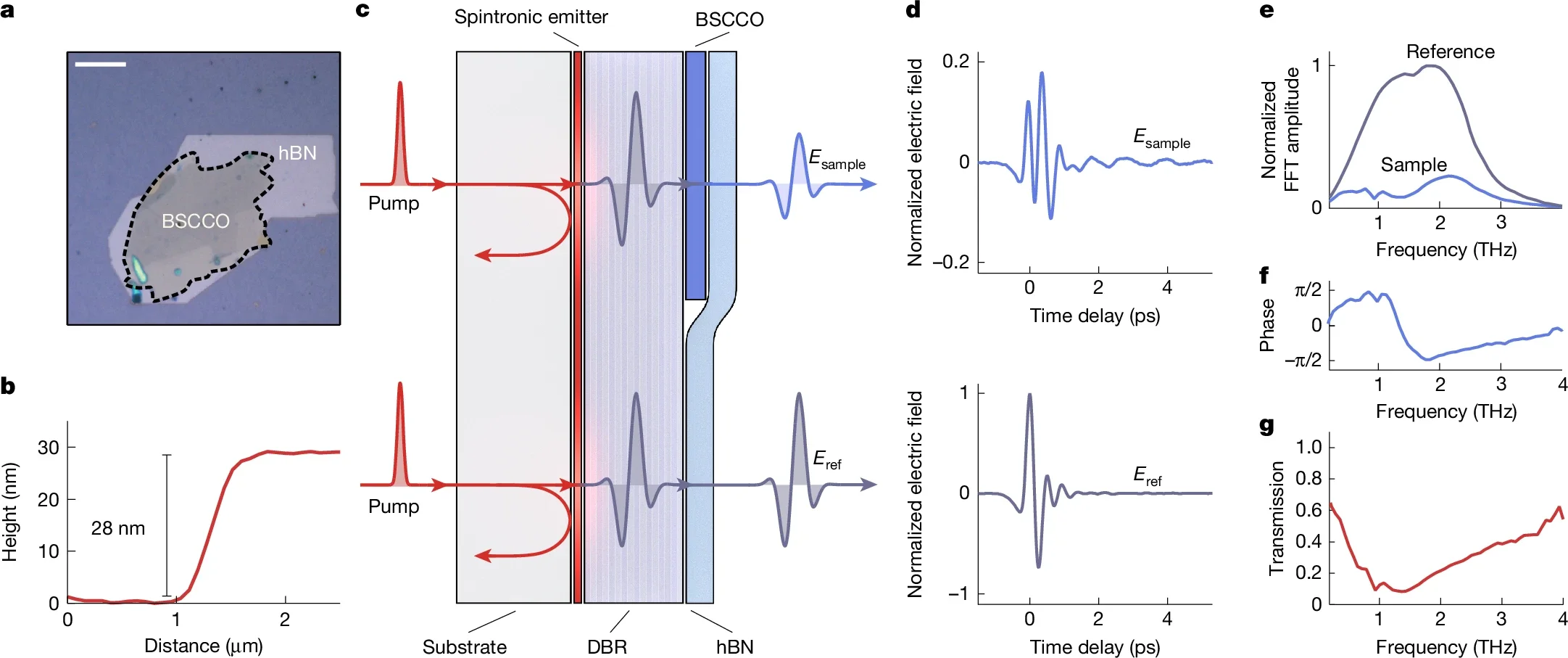

Their team built a terahertz microscope that squeezes terahertz waves down to microscopic sizes. That lets the light interact with tiny samples instead of washing over them.

The group tested the microscope on a high-temperature cuprate superconductor called bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide, or BSCCO (pronounced “BIS-co”). With the new setup, they saw superconducting electrons move together in a fresh, direct way.

“This new microscope now allows us to see a new mode of superconducting electrons that nobody has ever seen before,” says Gedik, the Donner Professor of Physics at MIT.

Terahertz radiation sits between microwaves and infrared on the electromagnetic spectrum. It vibrates more than a trillion times per second. That rhythm matches how atoms and electrons can jiggle inside materials.

Terahertz waves also bring a safety bonus. Like radio and microwaves, they are nonionizing. That means they do not carry enough energy to damage tissue. At the same time, terahertz waves can pass through many everyday materials, including fabric, cardboard, plastic, ceramics, and even thin brick walls.

So why has terahertz light not become a standard microscope tool? The problem is size. Terahertz wavelengths stretch hundreds of microns long. A light beam cannot focus into a spot smaller than its wavelength. That “diffraction limit” makes a terahertz spot too big for many microscopic targets.

“Our main motivation is this problem that, you might have a 10-micron sample, but your terahertz light has a 100-micron wavelength, so what you would mostly be measuring is air, or the vacuum around your sample,” von Hoegen explains. “You would be missing all these quantum phases that have characteristic fingerprints in the terahertz regime.”

The MIT team got around the diffraction limit by using spintronic emitters. These are stacks of ultrathin metal layers that can spit out sharp terahertz pulses after a laser hit.

When laser light strikes the multilayer stack, electrons respond in a chain of effects. The structure then emits a short burst of terahertz energy. The key move came next. The researchers placed a sample extremely close to the emitter. That trapped the terahertz field before it could spread out.

They also added a Bragg mirror, a multilayer reflector that filters light. The mirror blocks leftover near-infrared laser light from reaching the sample. It still lets the terahertz field through. That protects the superconductor from unwanted laser effects.

For the demonstration, the researchers studied an atomically thin BSCCO flake. They cooled it close to absolute zero so it turned superconducting. Then they scanned a laser spot to launch terahertz pulses and read the signal after it passed through the sample.

“We see the terahertz field gets dramatically distorted, with little oscillations following the main pulse,” von Hoegen says. “That tells us that something in the sample is emitting terahertz light, after it got kicked by our initial terahertz pulse.”

After more analysis, the team concluded they had excited a collective motion of the superconducting electrons. The electrons behaved like a frictionless fluid that sloshed back and forth at terahertz rates.

“It’s this superconducting gel that we’re sort of seeing jiggle,” von Hoegen says.

This kind of collective motion had been expected. But researchers had not directly visualized it this way before.

Superconductors can act like perfect electrical highways, but the deeper picture involves a shared electron wave. Paired electrons move in sync. That wave has an amplitude and a phase, often written as ψ = Δe^iχ.

When the superconductor gets disturbed, it can shake in more than one way. Some shakes mainly change the amplitude. Others mainly change the phase. In many materials, long-range electric forces push phase motion to very high energies. That makes it harder to study cleanly.

Cuprate superconductors like BSCCO change the story because they are built from CuO2 planes. Those planes couple weakly to each other. That weakness helps create low-energy modes that terahertz light can reach.

Inside each plane, though, the in-plane response can still hide at energies far above the superconducting gap. The trick is to make the material thin enough that a clear, low-energy in-plane mode appears. But that mode lives at finite momentum, which ordinary far-field terahertz methods cannot access.

The new subwavelength source solves that momentum problem. It launches an in-plane wave inside the thin BSCCO flake. Because the sample has edges, part of the wave can radiate out and become measurable.

One key sample in the study measured 28 nanometers thick, about 8 to 9 unit cells. The team encapsulated it in 30 nanometers of hexagonal boron nitride to slow degradation. They kept it under vacuum and below 150 K.

At 10 K, the transmitted terahertz pulse stretched and weakened compared with a reference signal. After the main pulse, coherent low-frequency oscillations appeared. Those oscillations did not show up away from the sample.

When the team converted the time signal into a spectrum, transmission showed a deep minimum near 1.4 THz. The transmission phase swung rapidly across that same feature.

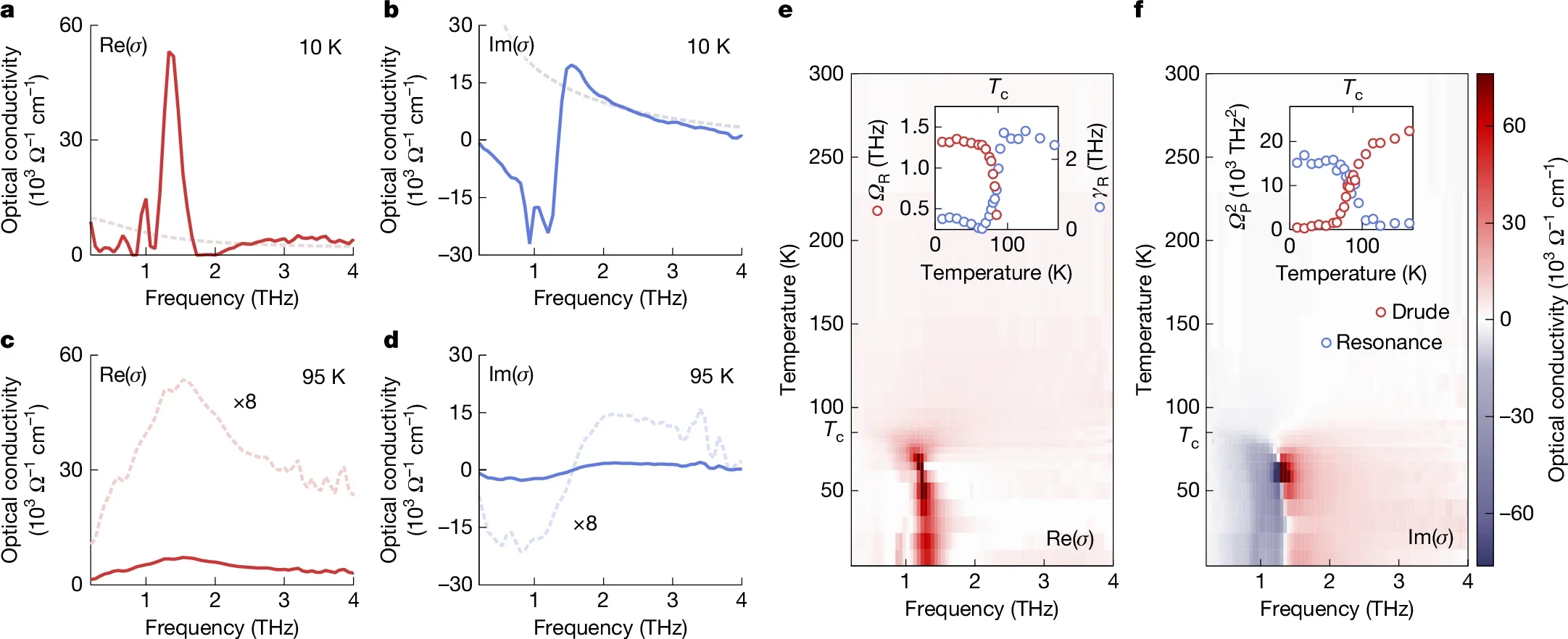

The researchers extracted an effective terahertz conductivity versus frequency. They cautioned that subdiffractive fields complicate exact numbers. Still, the patterns looked telling.

At 10 K, the dissipative part of the conductivity showed a narrow peak at 1.4 THz. Another part crossed from negative to positive. Together, those features matched a classic “collective resonance” fingerprint.

Temperature tests supported the idea. Just above the critical temperature, near 95 K, the resonance broadened. Around Tc = 87 K, the resonance faded within about 10 K. The frequency dropped and damping rose as Tc approached.

The team also scanned the pump beam across the sample. That produced phase-resolved maps with subwavelength detail. At frequencies above resonance, the amplitude map traced the flake’s outline. Near and below resonance, patterns depended on geometry and polarization.

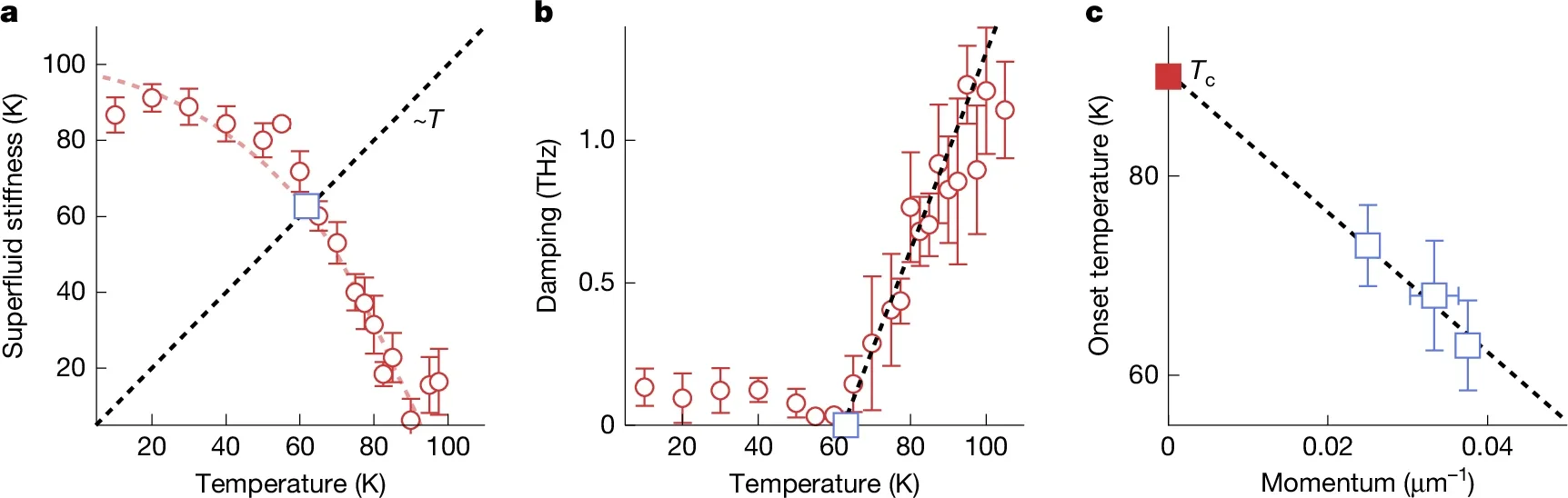

In a second, nearly rectangular sample, the resonance shifted when polarization aligned with the long side versus the short side. That pointed to a mode whose wavelength ties to sample dimensions. As temperature rose, the resonance softened while the wavelength stayed nearly fixed. Geometry set the momentum, while temperature changed the frequency.

The researchers link the behavior to a two-dimensional in-plane “superfluid plasmon,” a collective wave tied to the superconducting condensate. They report a plasmon phase velocity vp = 0.099 ± 0.003c, close to a literature estimate of 0.11c.

They also argue that the damping rise fits a two-dimensional picture involving vortex–antivortex unbinding. In simple terms, parts of the superconducting order can lose phase coherence at certain length scales before the whole sample turns normal.

This microscope gives researchers a new way to test how superconductors behave on the small scales that matter for devices. By revealing terahertz-scale electron motion directly, the method could help scientists sort which materials hold the most promise for better superconductors, including long-sought room-temperature versions.

The approach could also speed work on terahertz technology itself. “There’s a huge push to take Wi-Fi or telecommunications to the next level, to terahertz frequencies,” von Hoegen says. “If you have a terahertz microscope, you could study how terahertz light interacts with microscopically small devices that could serve as future antennas or receivers.”

Because terahertz waves can penetrate many materials without ionizing damage, improved terahertz sources and detectors could also support safer imaging tools. The new microscope helps identify materials that emit and receive terahertz radiation well, which could guide future sensor design.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Global first: Physicists use light to reveal quantum vibrations in a superconducting material appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.