In a UC Irvine office, Dorota Skowronska-Krawczyk studies a video that has changed her view of a deep-sea legend. “You see it move its eye,” says the University of California, Irvine associate professor of physiology and biophysics, pointing at a Greenland shark drifting in dark Arctic water. “The shark is tracking the light—it’s fascinating.”

Skowronska-Krawczyk and her co-authors argue that the world’s longest-living vertebrate still sees; and does so after more than a century of life. Their new work, published in Nature Communications, also links the shark’s eye health to DNA repair, offering clues about how tissues can stay functional for an unusually long time.

The study includes evolutionary analysis by University of Basel researchers Walter Salzburger and Lily G. Fogg. It also draws on samples collected by marine biologists at the University of Copenhagen, led by professor John Fleng Steffensen, with collaborators Peter G. Bushnell of Indiana University South Bend and Richard W. Brill of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

Greenland sharks, known scientifically as Somniosus microcephalus, can live as long as 400 years. They range from the North Atlantic into the Arctic Ocean, tolerate temperatures down to −1.1°C, and dive to nearly 3,000 meters. Many carry a copepod parasite, Ommatokoita elongata, attached to the cornea. The parasite can make the eye look cloudy and damaged, which is one reason scientists long suspected these sharks might be functionally blind.

Skowronska-Krawczyk traces her curiosity to a 2016 paper by Steffensen published in Science. “One of my takeaway conclusions from the Science paper was that many Greenland sharks have parasites attached to their eyes—which could impair their vision,” she says. “Evolutionarily speaking, you don’t keep the organ that you don’t need. After watching many videos, I realized this animal was moving its eyeballs toward the light.”

That observation pushed the team to test a straightforward idea: if the shark still relies on vision, its retina, vision genes, and light-sensing pigments should still work.

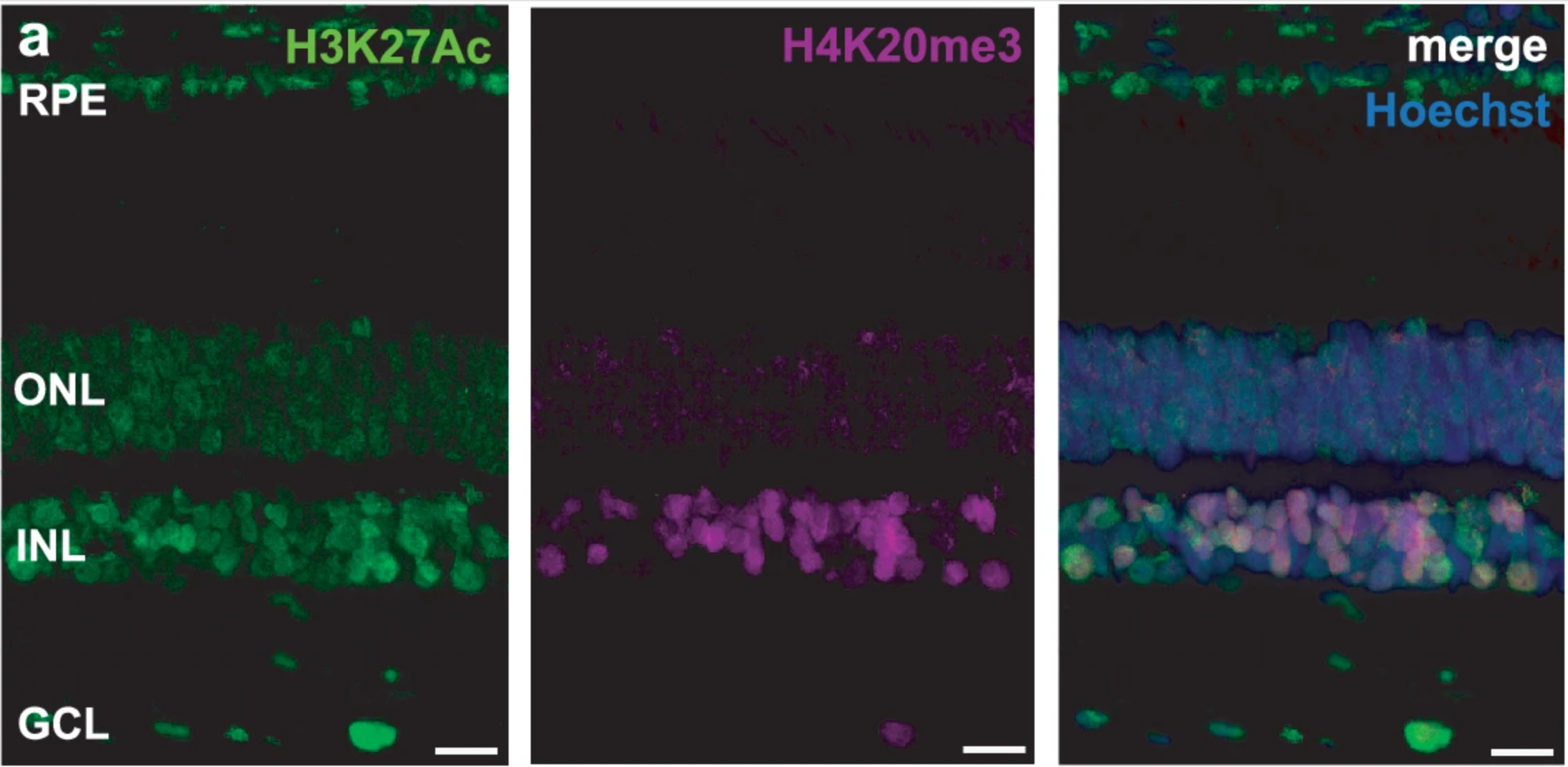

The Greenland shark’s retina turned out to be built for darkness. Instead of a “duplex” retina with both rods and cones, the tissue was a pure-rod retina. Rods are the cells that support vision in dim light. In the samples, rods were densely packed and elongated, and inner retinal layers were relatively thin. That pattern matches other species adapted to low light.

“Our research team examined retinas from adult sharks estimated to be more than a century old. We found no obvious signs of retinal degeneration in the tissue we inspected. We also ran a TUNEL assay, a test that can detect DNA fragmentation associated with cell death. The assay lit up only in a positive control where DNA breaks were deliberately induced. In untreated Greenland shark sections, we detected no TUNEL-positive cells,” Skowronska-Krawczyk told The Brighter Side of News.

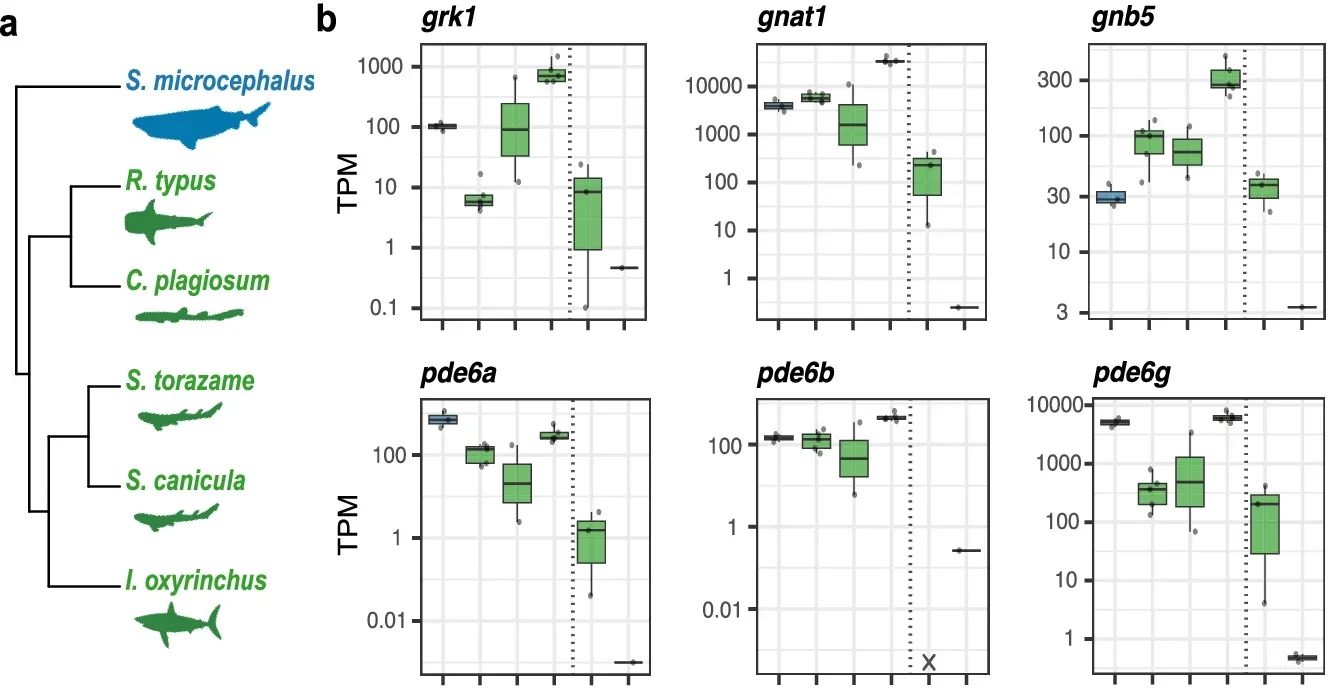

Genetic results reinforced the anatomy. The researchers assembled a draft genome and searched for phototransduction genes, the set that turns light into nerve signals. They recovered functional copies of the full rod-based toolkit, including rh1, sag, gnat1, and several others needed for rod signaling. Cone-associated genes, by contrast, were missing or pseudogenized, meaning they carried changes that likely prevent them from functioning.

The opsin story was similar. The shark carried a single functional rod opsin, rh1. A cone opsin, rh2, showed evidence of pseudogenization. The team also reported that a non-visual opsin gene, opn4, was pseudogenized, which they linked to the shark’s deep, dim environment and the lack of a clear circadian rhythm in its daily vertical movements.

To check whether this rod system was more than genetic potential, the team examined gene activity in the retina. Bulk retinal transcriptomes showed that key rod genes were expressed at biologically relevant levels. Cone phototransduction genes showed low or no expression, which fit the pure-rod anatomy.

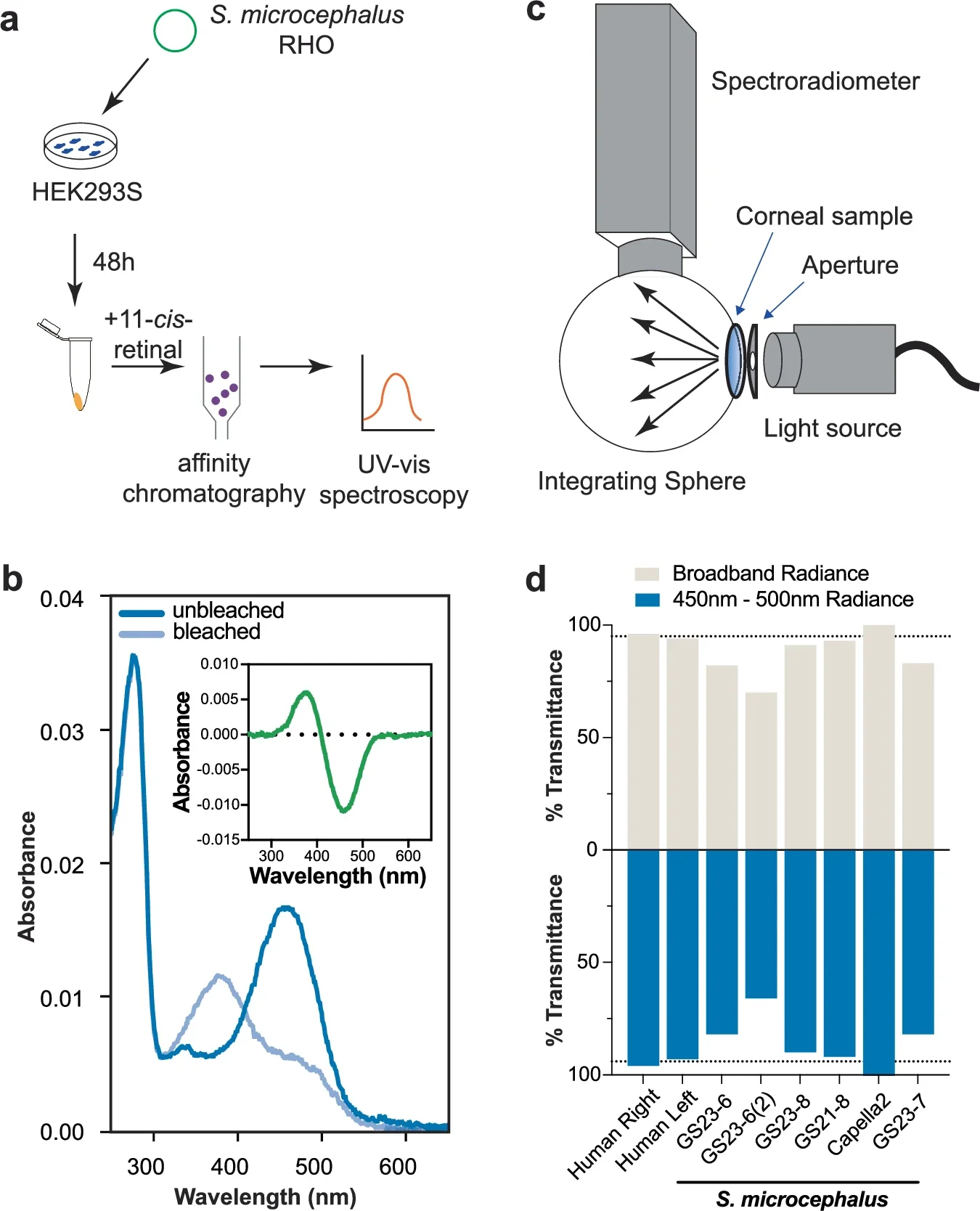

They then tested the shark’s rhodopsin, the rod visual pigment. In lab expression experiments, the pigment’s maximum absorbance wavelength was 458 nanometers. That value is blue-shifted compared with many shallow-water sharks, consistent with a deep-sea setting where blue wavelengths dominate what little light remains.

The study also asked whether parasites block too much light for vision to matter. Using a tunable light source and spectroradiometer setup, the team measured corneal transmission in fixed shark corneas and compared it with fixed human donor corneas. Human corneas averaged about 95% transmittance across 425–600 nanometers. Shark corneas ranged from 70% to 100%, even though the tested corneas had parasites bound to corneal edges. In the blue band most relevant to the shark’s rhodopsin, shark corneas ranged from 66% to 100%. The measurements suggest that substantial light can still reach the retina.

Back at UC Irvine, Emily Tom, a Ph.D. student and physician-scientist in training in Skowronska-Krawczyk’s lab, handled much of the tissue work. “I opened the package, and there was a giant, 200-year-old eyeball sitting on dry ice just staring back at me,” Tom says, laughing. “We’re used to working with mouse eyeballs, which are the size of a papaya seed, so we had to figure out how to scale up to a baseball-sized eyeball. Luckily, Dorota is very hands-on, both in her mentoring style and in the lab—which you don’t see a lot of with professors.”

Tom remembers the sensory reality of the work, too. When the eye thawed enough to sample, “The lab smelled like a fish market,” she says.

This study strengthens the case that extreme longevity does not have to mean failing vision. The Greenland shark appears to preserve retinal structure, maintain active rod signaling, and keep a pigment tuned to available blue light. If those features hold across more individuals and ages, the shark becomes a living test case for how eye tissues resist wear over time.

The DNA repair angle may be the most useful lead for human health. The researchers focused on the ERCC1-XPF repair complex, which has been linked to retinal health and aging in other organisms. They reported that the longest-lived shark species, including Greenland sharks, retained ercc1, while shorter-lived sharks lacked it; and Greenland sharks showed elevated expression of ercc4 (xpf) compared with other sharks. That pattern suggests a possible molecular route for protecting the retina across decades, or centuries.

Skowronska-Krawczyk sees the work as a starting point for preventing age-related vision loss. She points to diseases such as macular degeneration and glaucoma as targets for future insight. “What I love about my work is that we are the first in the world to see results—at the forefront, finding new mechanisms, rules and discoveries,” she says. “Then, being able to share this joy with students—that’s the best part of it.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Greenland sharks reveal that extreme longevity does not have to mean failing vision appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.