A new study from Northwestern University is reshaping how scientists think about brain evolution. The research suggests that the gut microbiome does more than aid digestion. It may also influence how brains develop, function, and meet their high energy needs.

The work is led by Katie Amato, an associate professor of biological anthropology at Northwestern and the study’s principal investigator. Her team set out to explore a long-standing puzzle in evolutionary biology. Humans have the largest brains relative to body size among primates, yet brains are extremely costly organs to build and maintain. They consume large amounts of energy, especially glucose. How evolution met those demands has remained unclear.

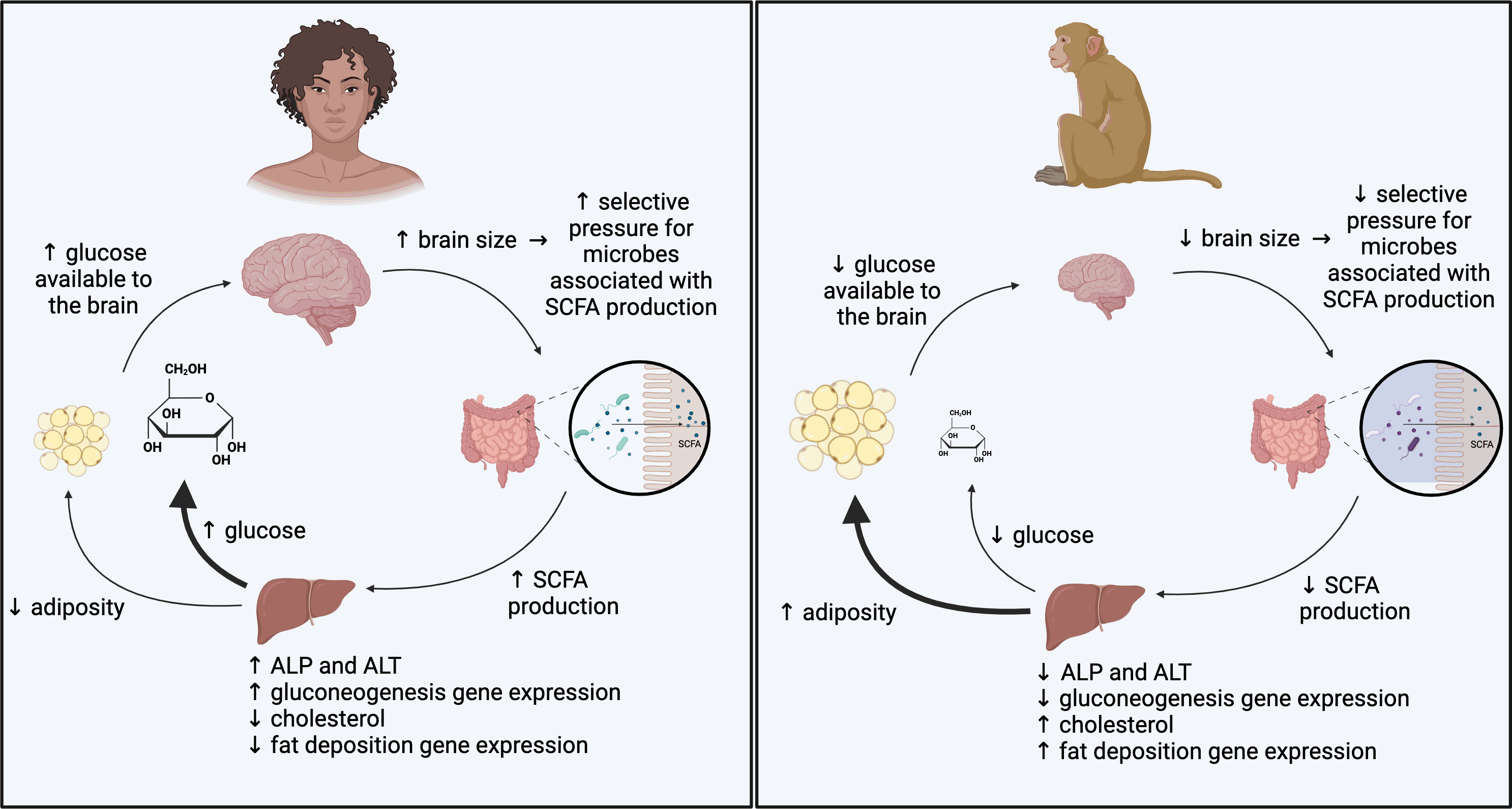

Amato’s group focused on a possible contributor that has received little attention in this context: the gut microbiome. These communities of microbes help break down food, produce metabolites, and regulate metabolism. Previous work from Amato’s lab showed that microbes from larger-brained primates generate more metabolic energy when transferred into mice. The new study goes further by examining whether those microbes also change how the brain itself functions.

“Our study shows that microbes are acting on traits that are relevant to our understanding of evolution, and particularly the evolution of human brains,” Amato said.

To explore the question, the researchers designed a controlled laboratory experiment using germ-free mice. These mice are raised without any microbes, allowing scientists to precisely control which microbial communities they receive.

“Our team implanted gut microbes from three primate species into separate groups of mice. Two of the donor species have relatively large brains: humans and squirrel monkeys. The third, the macaque, has a smaller brain relative to body size. The goal was to separate the effects of brain size from evolutionary relatedness,” Amato explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Within eight weeks of altering the mice’s microbiomes, clear differences emerged in how their brains functioned. Mice that received microbes from large-brained primates showed distinct patterns of brain gene activity compared with mice that received microbes from macaques,” he continued.

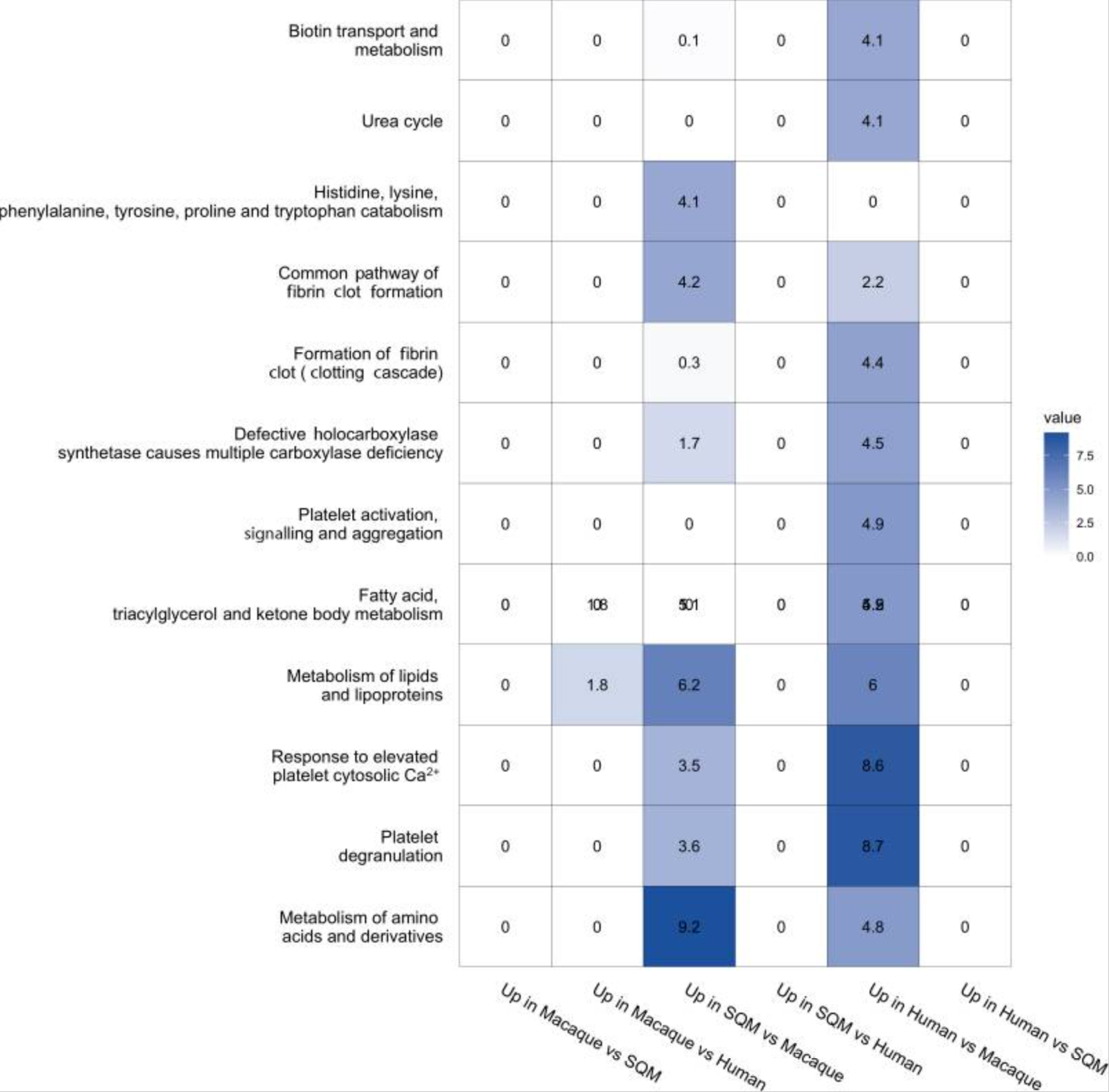

In mice with human and squirrel monkey microbes, genes linked to energy production and synaptic plasticity became more active. Synaptic plasticity underlies learning and memory by allowing connections between neurons to change. In contrast, mice with macaque microbes showed lower activity in these same processes.

“What was super interesting is we were able to compare data we had from the brains of the host mice with data from actual macaque and human brains, and to our surprise, many of the patterns we saw in brain gene expression of the mice were the same patterns seen in the actual primates themselves,” Amato said. “In other words, we were able to make the brains of mice look like the brains of the actual primates the microbes came from.”

The researchers also found that microbes from larger-brained primates boosted the brain’s ability to produce and use energy. Human-derived microbes, in particular, increased the expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, a key process cells use to generate energy.

These gene changes tracked closely with microbial pathways tied to glucose metabolism and gluconeogenesis, the production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources. Glucose is the brain’s primary fuel, and even small changes in its availability can shape brain growth and activity.

The findings suggest that shifts in gut microbes may have helped support the energetic costs that came with larger brains during primate evolution. Even microbes from squirrel monkeys, which are more distantly related to humans than macaques are, produced brain effects similar to those seen with human microbes. That pattern points to brain size, not ancestry, as the key factor.

One of the most unexpected results involved genes tied to brain health. In mice that received microbes from smaller-brained primates, the researchers observed patterns of gene expression linked to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism.

Scientists have long noted correlations between the gut microbiome and conditions such as autism. However, most evidence has been observational. Direct proof that microbes can shape brain development has been limited.

“This study provides more evidence that microbes may causally contribute to these disorders; specifically, the gut microbiome is shaping brain function during development,” Amato said. “Based on our findings, we can speculate that if the human brain is exposed to the actions of the ‘wrong’ microbes, its development will change, and we will see symptoms of these disorders, i.e., if you do not get exposed to the ‘right’ human microbes in early life, your brain will work differently, and this may lead to symptoms of these conditions.”

The researchers emphasize that the findings are preliminary. Only three primate species were studied, and mouse brains are not human brains. Still, the results offer rare experimental evidence that gut microbes can drive meaningful changes in brain gene activity.

The study takes an evolutionary view of brain development. Humans and several other primates evolved unusually large brains, alongside metabolic changes that increased circulating glucose. The new data suggest the gut microbiome may have played a supporting role in that transition.

By transferring primate microbes into mice, the team showed that species-specific microbial communities can reproduce brain gene expression patterns seen in the donor species. That result hints at a deep biological link between microbes, metabolism, and brain evolution.

Amato sees this as a starting point for broader research. She hopes future studies will examine more species and look at how microbial effects change over time and during early development.

“It’s interesting to think about brain development in species and individuals and investigating whether we can look at cross-sectional, cross-species differences in patterns and discover rules for the way microbes are interacting with the brain, and whether the rules can be translated into development as well,” she said.

The findings could influence how scientists study both brain evolution and brain disorders. By showing that gut microbes can shape brain energy use and gene activity, the research opens new paths for understanding why human brains are so energetically demanding. It also suggests that early-life microbial exposure may matter more for brain development than previously thought.

In the long term, this work could guide research into prevention or treatment strategies for neurodevelopmental conditions. If specific microbial patterns support healthy brain development, future therapies might aim to restore or maintain those microbes during critical developmental windows.

The study also encourages researchers to take an evolutionary lens when examining modern brain disorders, linking ancient biological changes to present-day health.

Research findings are available online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Gut microbes are reshaping how scientists think about brain evolution appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.