A major scientific breakthrough has identified the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) as the leading cause of multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic inflammatory disease that affects nearly 3 million people worldwide. This discovery, based on data from more than 10 million U.S. military service members, could pave the way for new vaccines and treatments that could one day prevent or even cure MS.

The results come from a 20-year study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense.

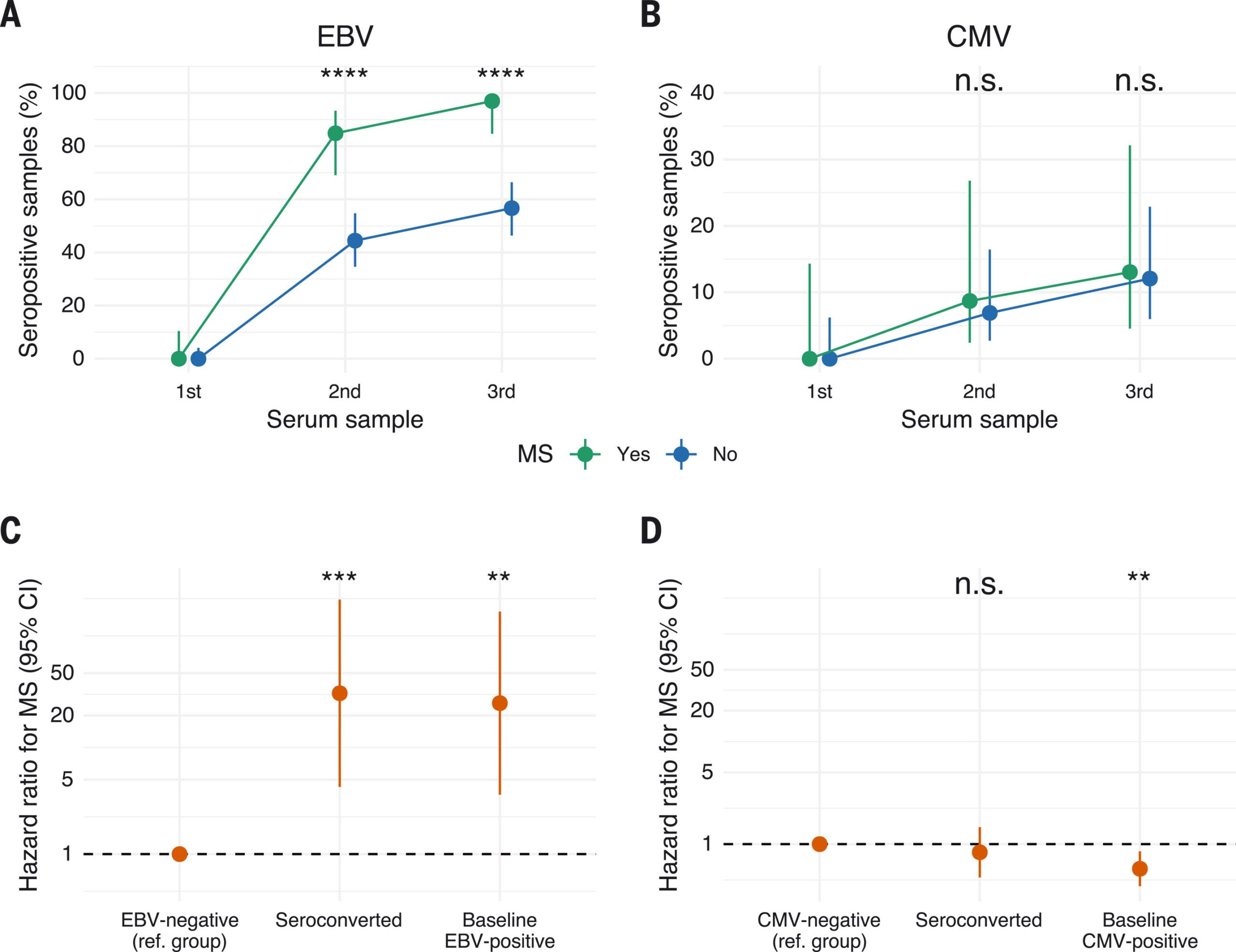

The findings, published in the journal Science, provide compelling evidence that infection with EBV dramatically increases the risk of developing MS later in life. Researchers found that the risk of MS rises 32-fold after an individual becomes infected with EBV, while infection with other viruses showed no similar increase.

MS damages the protective covering of nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord, known as the myelin sheath. This causes communication problems between the brain and the rest of the body. The result can be severe: vision loss, paralysis, chronic pain, and cognitive decline. Until now, scientists have not been able to determine what exactly triggers MS.

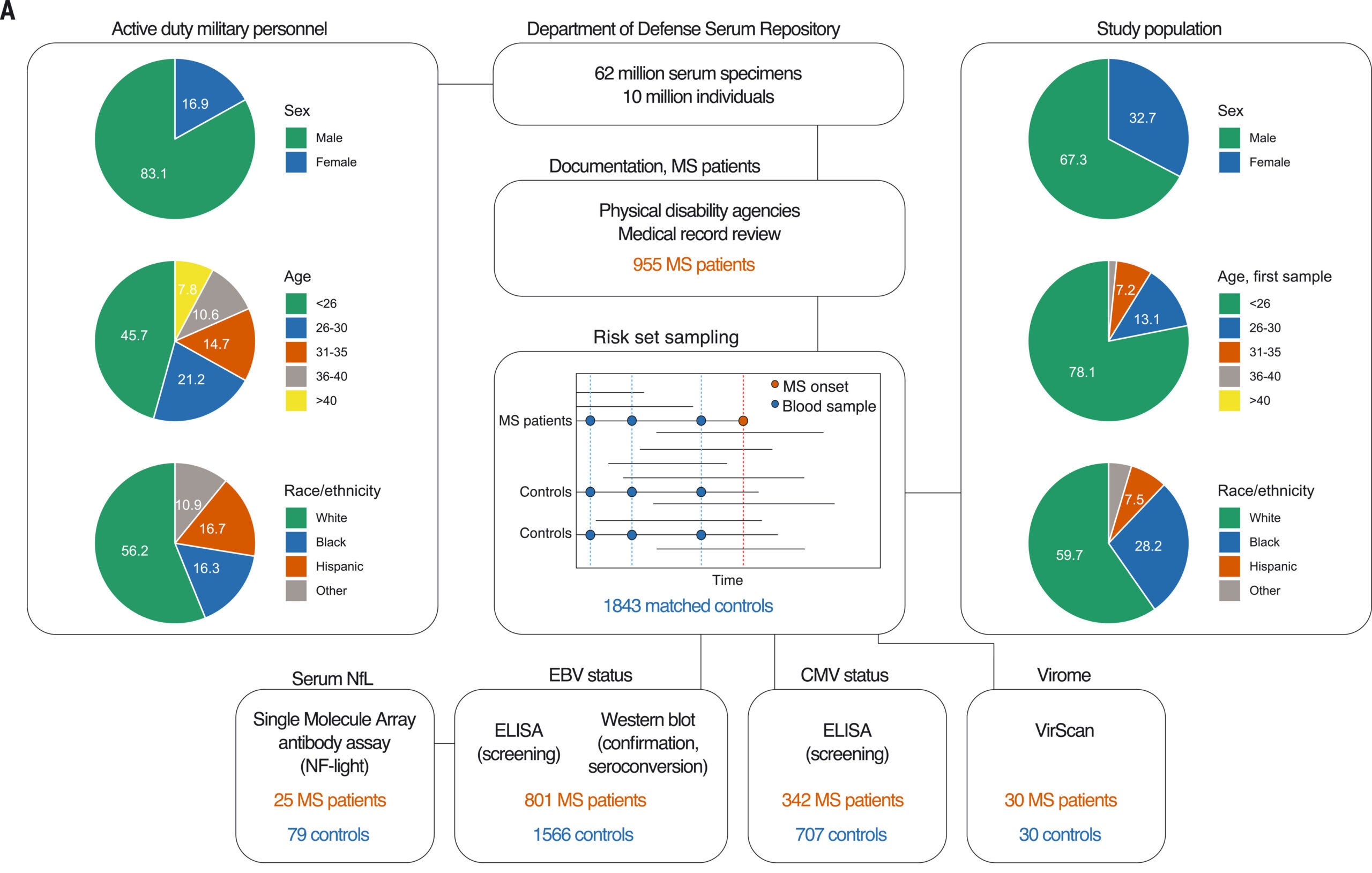

The study analyzed over 62 million blood samples taken from active-duty U.S. military personnel between 1993 and 2013. These service members are routinely screened for HIV, and their leftover serum samples are stored in the Department of Defense Serum Repository. The database allowed researchers to track blood markers from the start of military service and monitor changes over time.

From this pool, the team identified 955 individuals who were diagnosed with MS during service. Each of these cases was matched to controls—fellow service members who shared similar age, sex, race, and branch of service but did not develop MS. The research focused on individuals who were EBV-negative at the beginning of their service. Among them, nearly all who later developed MS eventually became EBV-positive before the disease appeared.

In total, 801 MS cases had available samples to evaluate EBV status. Only one person remained EBV-negative in their last available sample before MS onset. The vast majority—97%—had seroconverted to EBV-positive before developing symptoms. By contrast, just 57% of non-MS controls became EBV-positive, a pattern consistent with population averages.

The average time between EBV infection and the onset of MS was about 7.5 years, giving scientists a clearer timeline for how the disease develops after the virus enters the body.

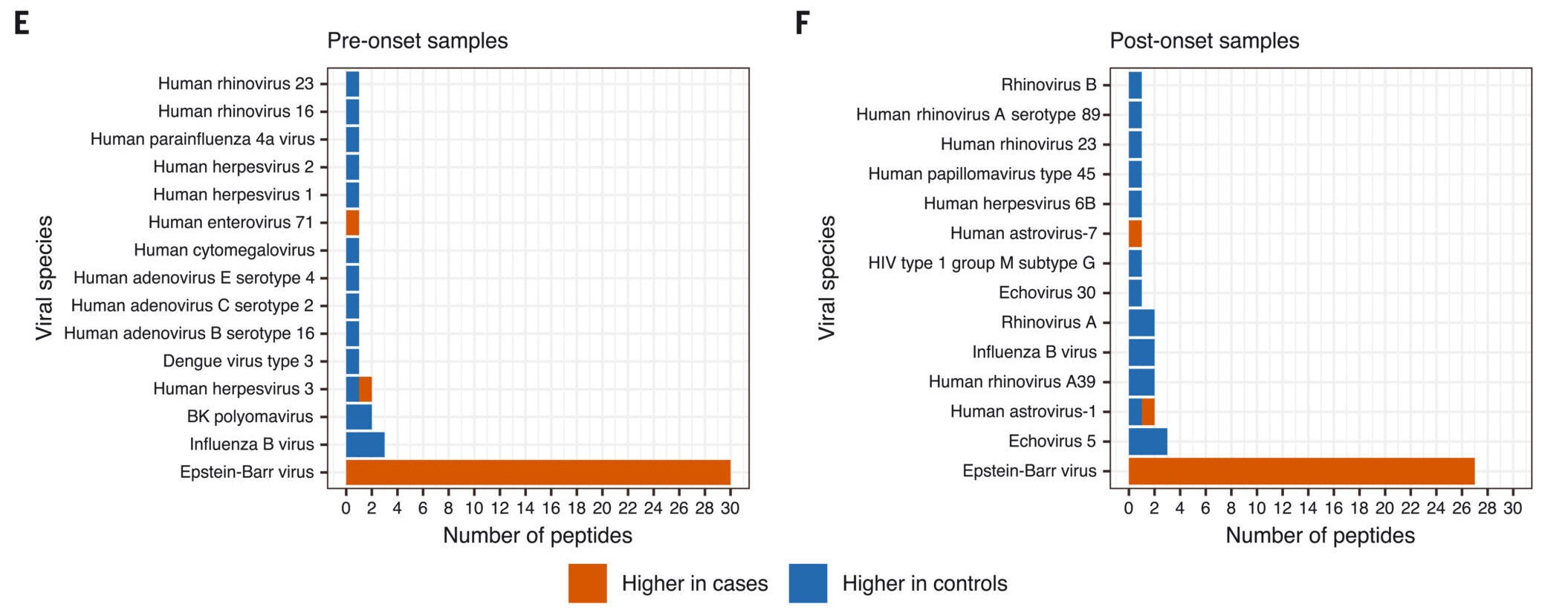

To ensure the results were not influenced by other factors, the team conducted several control tests. They looked at cytomegalovirus (CMV), a herpesvirus also transmitted through saliva and common in the population. CMV infection showed no link to MS, reinforcing that the connection was specific to EBV.

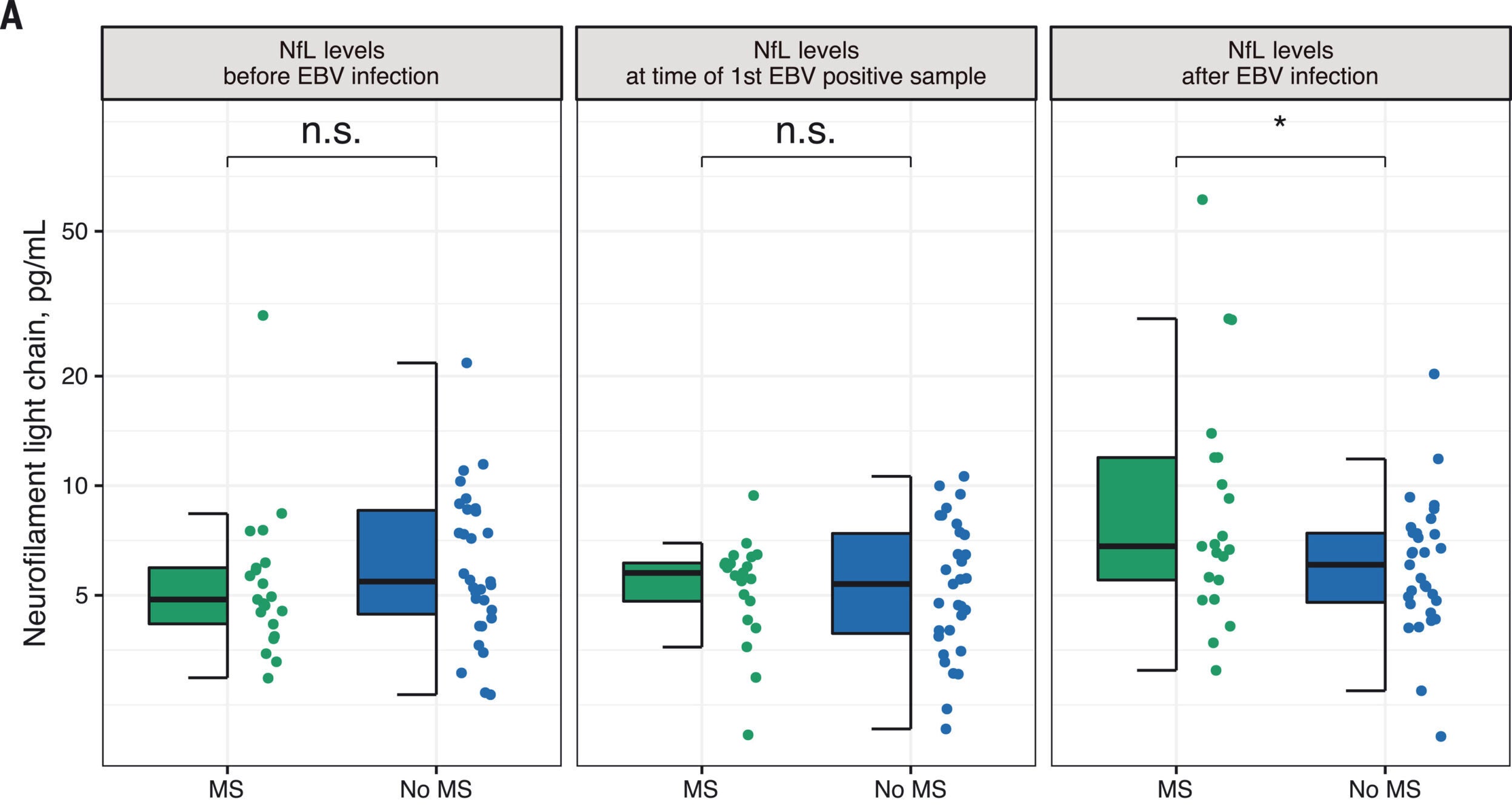

They also measured serum levels of neurofilament light chain (sNfL), a protein that signals nerve damage. In individuals who were EBV-negative at first, sNfL levels remained normal until after they became EBV-positive. This supports the view that EBV infection occurred before any signs of neurological damage appeared.

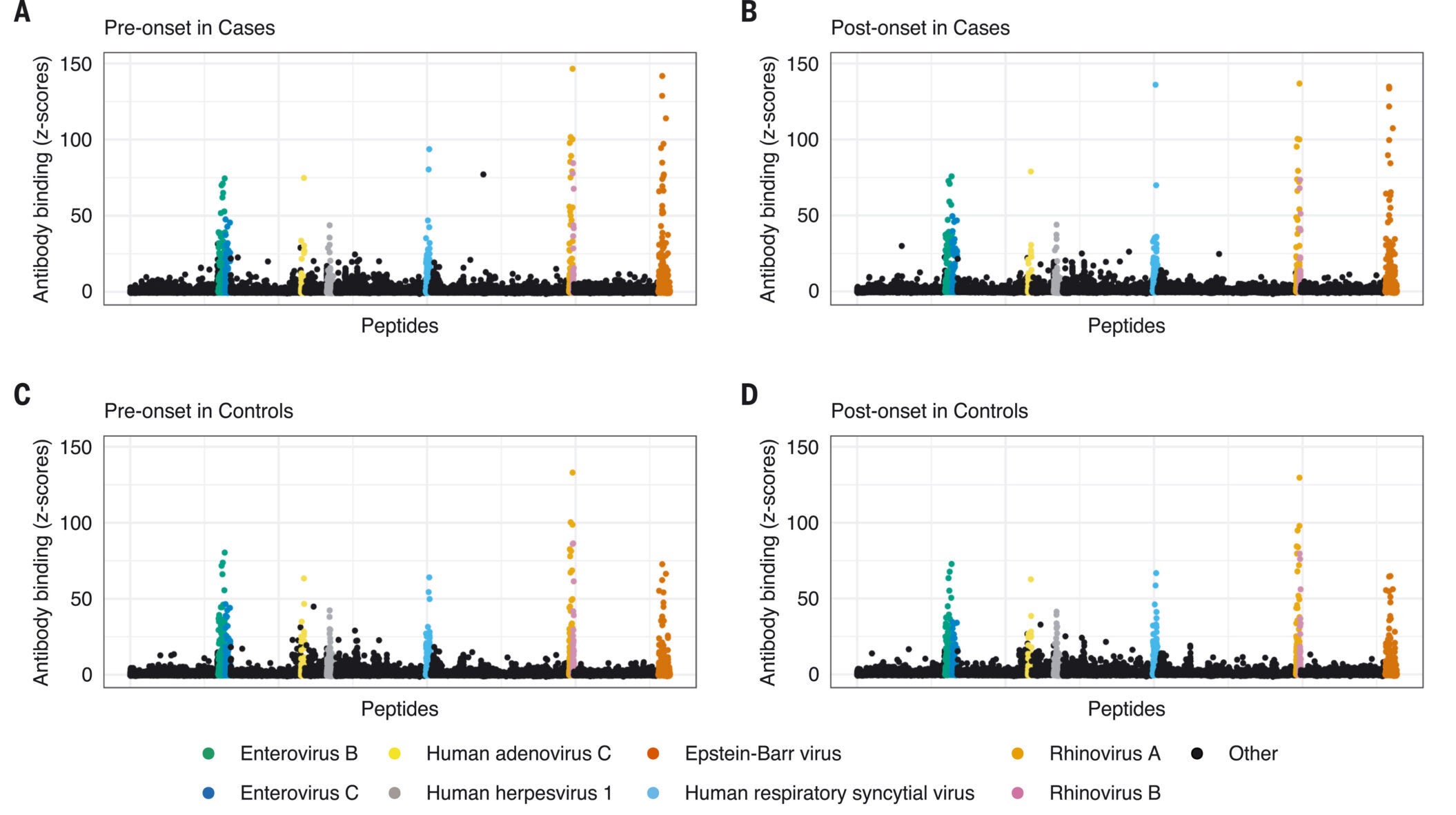

To further rule out the chance that MS caused changes in the immune system that made people more susceptible to EBV, researchers scanned for antibodies against over 200 known human viruses. They found no significant differences in immune responses to other viruses—only EBV stood out.

The study authors addressed two main alternative explanations: confounding and reverse causation. For confounding to explain the link, there would need to be an unknown factor that increases the risk of both EBV infection and MS by over 60 times. No such factor is known.

The second explanation—reverse causation—suggests MS may alter the immune system and make individuals more vulnerable to EBV. But this too was dismissed. MS patients did not show unusual antibody responses to other viruses before or after symptom onset. sNfL levels only rose after EBV infection, and the long delay between infection and symptoms further supports a cause-effect relationship.

One patient in the study remained EBV-negative just before being diagnosed with MS. This outlier could be due to several possibilities: infection after the last blood sample, failure to mount an immune response, or a misdiagnosis. Importantly, such rare exceptions are common in medicine and do not undermine the strong overall findings.

Alberto Ascherio, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard, has spent over 25 years pursuing the cause of MS. His team’s work has earned widespread recognition, including the 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. Ascherio shared the honor with Steven Hauser of the University of California, San Francisco, who developed B-cell-based treatments for MS.

Ascherio was drawn to the mystery of MS because of the lack of answers and the human cost of the disease. “You really need to believe in what you’re doing, to have a vision,” he said. He credits the long-term collaboration with the U.S. military for making the discovery possible.

The study also reflects the power of epidemiology. By tracking health outcomes in a large, stable population over time, scientists were able to uncover patterns that had eluded researchers for decades.

EBV is incredibly common—about 95% of adults carry the virus, usually acquired in childhood or adolescence. It can cause mononucleosis but often produces no symptoms. Once in the body, it hides in B cells and remains there for life. EBV has also been linked to certain cancers, including Hodgkin lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Now, its role in MS is considered almost certain. The findings point to an urgent need for a vaccine. Several biotech companies are currently developing EBV-targeting vaccines and antiviral drugs. If successful, these treatments could stop MS before it begins.

Existing MS treatments include anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, which eliminate memory B cells—the same cells where EBV hides. These therapies have shown success, but they come with risks, such as increased infections and the need for IV infusion. A vaccine or oral antiviral would offer a safer and more accessible alternative.

“Currently there is no way to effectively prevent or treat EBV infection,” said Ascherio. “But an EBV vaccine or targeting the virus with EBV-specific antiviral drugs could ultimately prevent or cure MS.”

The implications go beyond MS. Ascherio and his team are also investigating viral links to other neurological diseases, including Parkinson’s, ALS, and potentially Alzheimer’s. Their work suggests that viral infections might act as hidden triggers for these conditions, interacting with genetic and environmental factors.

To pursue this line of research, Ascherio says more funding is needed. “It’s like having the Webb Space Telescope and not being able to launch it,” he explained, highlighting the importance of continued investment in brain science.

The EBV-MS connection stands as one of the most significant advances in neurology in recent decades. It marks the first time researchers have identified a clear cause for a major neurodegenerative disease. And with this new understanding, hope is rising for prevention, better treatment, and, someday, a cure.

Over the past three years, MS treatment has seen both new FDA‑approved therapies and next‑generation investigational approaches. Several approaches are summarized below.

The landscape is evolving rapidly, with several pivotal Phase III trials underway and novel therapy classes likely to reshape MS care within the next few years.

The Mayo Clinic explains that multiple sclerosis (MS) can cause a wide range of symptoms that vary from person to person and may change over time. These differences often depend on which nerve fibers are affected. Many symptoms involve movement, such as:

Vision issues are also frequent and may include:

Other symptoms of MS may include:

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Harvard study finds common virus triggers multiple sclerosis in 97% of cases appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.