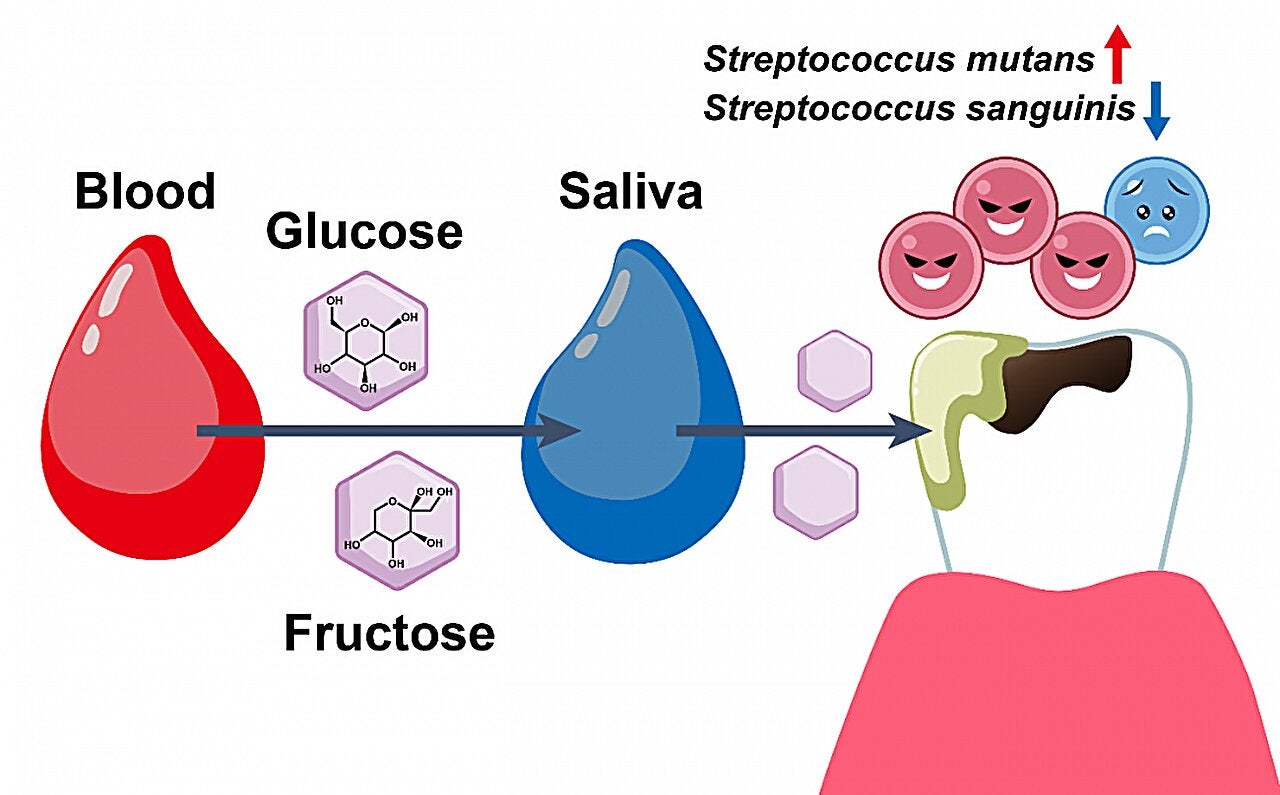

Type 2 diabetes has long been linked to heart disease, nerve damage, and vision loss. Now scientists say it also changes what happens inside your mouth. New research from the University of Osaka shows that high blood sugar does not stay in the bloodstream. It slips into saliva, where it feeds harmful bacteria and sets the stage for cavities.

Tooth decay, known medically as dental caries, does not unfold from sugar alone. Cavities form when certain microbes cling to the surface of teeth and turn sugars into acids. These acids slowly wear away the outer enamel layer. Diet and brushing matter, but this study shows another force at work for people with type 2 diabetes. Sugar does not reach teeth only through food. When blood sugar stays high, glucose and fructose cross into saliva directly from the blood.

Once sugar enters saliva, it becomes fuel. Bacteria that thrive on sugars gain an edge. They grow faster, produce more acid, and crowd out species that usually help keep the mouth balanced.

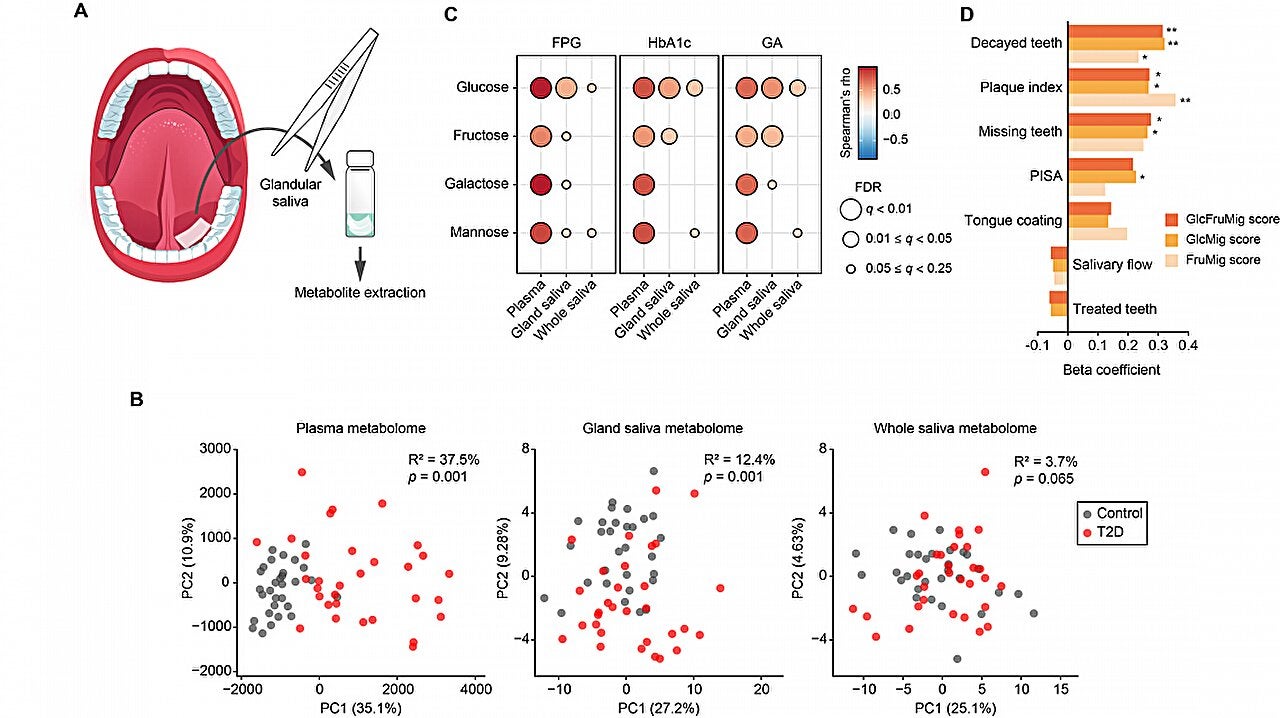

Researchers studied 61 adults, including 31 people with type 2 diabetes and 30 people without the disease. For the diabetes group, testing took place twice, once at hospital admission and again after two weeks of intensive blood sugar treatment. Scientists collected blood, saliva taken straight from glands, and whole saliva that already held bacteria.

This three-part approach let researchers follow sugar from the bloodstream to the tooth surface. They could see what arrived in saliva before bacteria touched it and how much remained after microbes had their turn.

A major advance in the study was the way saliva was collected. Instead of testing only whole saliva, which is already changed by bacteria, scientists took samples directly from salivary glands under the tongue. This glandular saliva offered a cleaner look at what enters the mouth from blood.

Results showed clear differences across blood, glandular saliva, and whole saliva. Blood reflected diabetes most strongly. Whole saliva showed the weakest link. Glandular saliva fell in between. This pattern mattered, because bacteria in whole saliva had already changed much of what entered the mouth.

Scientists detected 78 small chemical compounds in blood, 125 in glandular saliva, and 143 in whole saliva. Fifty three were found in all three. That overlap proved that materials regularly pass from blood into saliva.

Glucose and fructose stood out. In people with diabetes, these sugars were much higher in blood. They dropped gradually across glandular saliva and whole saliva, showing that bacteria consumed them once they reached the mouth.

Another substance, called 1,5-anhydroglucitol, worked in the opposite direction. Its level fell as blood sugar rose. It stayed low in saliva as well. Doctors already use this compound as a sign of poor glucose control, and the new data confirm its role as a warning signal.

Statistics told the same story. Diabetes explained nearly 38 percent of blood chemistry changes, about 12 percent of glandular saliva changes, and only 4 percent of whole saliva changes. Whole saliva had already been altered too much by bacteria to reflect what arrived from blood.

To estimate how much sugar actually arrived at the tooth surface, researchers developed what they called a “saccharide migration score.” The score combined levels of glucose and fructose in blood, glandular saliva, and whole saliva into one measure.

Participants with higher scores were far more likely to have cavities and thicker plaque. The score captured three steps. First, it measured how much sugar circulated in blood. Second, it tracked how much entered saliva glands. Third, it showed how much remained after bacteria fed on it.

Even after adjusting for age and sex, higher sugar movement from blood to saliva matched worse dental health. The message was simple. The more sugar leaking into saliva, the easier it becomes for decay to start.

Researchers also looked at the types of microbes living on participants’ teeth. DNA testing showed striking differences between people with high and low sugar migration.

Helpful species declined. Among them were Streptococcus sanguinis, Corynebacterium durum, and Rothia aeria. These bacteria usually help keep the mouth stable. In their place, sugar loving microbes spread.

At the top of that list was Streptococcus mutans, a well known cause of cavities. Other microbes also grew, including Veillonella parvula, Scardovia wiggsiae, and Bifidobacterium dentium. These species excel at breaking down sugars and producing acid.

The bacteria also changed what they did. Genes linked to sugar breakdown, sugar storage, and fast energy use became more common. Enzymes tied to glycolysis, the main sugar burning process, rose sharply.

Fructose handling was a key shift. Enzymes that process fructose increased. So did transport systems that ferry sugar into bacterial cells. At the same time, lactic acid levels rose in saliva. Lactic acid is one of the main acids that damage enamel.

Together, these changes showed that blood sugar does not just sweeten the mouth. It reshapes the entire bacterial ecosystem toward decay.

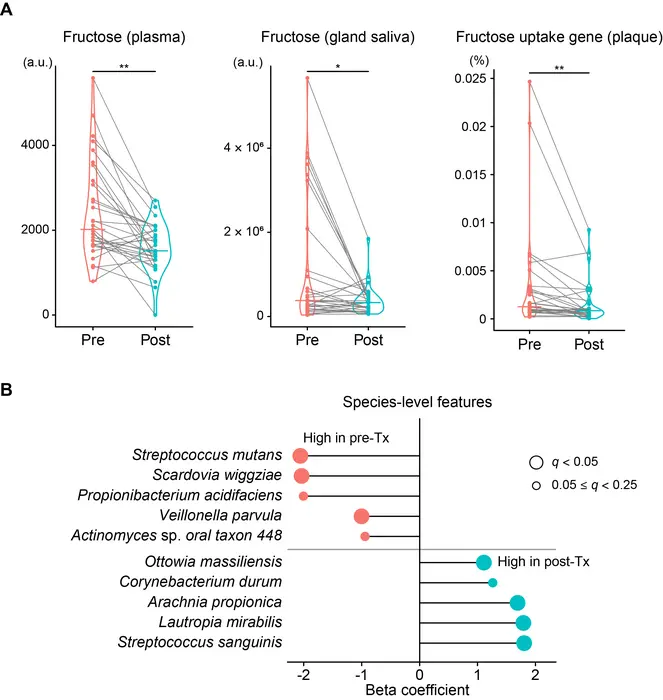

For patients with diabetes, the story did not end in decay. After two weeks of careful hospital treatment, blood sugar levels fell fast.

Average A1C dropped from 9.1 percent to 8.4 percent. Fasting glucose declined from 8.1 to 6.1 millimoles per liter. These shifts were medical wins by themselves, but they also changed what happened inside the mouth.

Fructose levels fell sharply in blood and glandular saliva. As sugar supplies dropped, microbes responded. Enzymes that process fructose decreased. Streptococcus mutans faded back. Helpful species began to return.

No dental treatment occurred during those two weeks. Brushing habits did not change. Only blood sugar improved.

That result made one point clear. Good diabetes control can help restore balance in the mouth, not just protect the heart or kidneys.

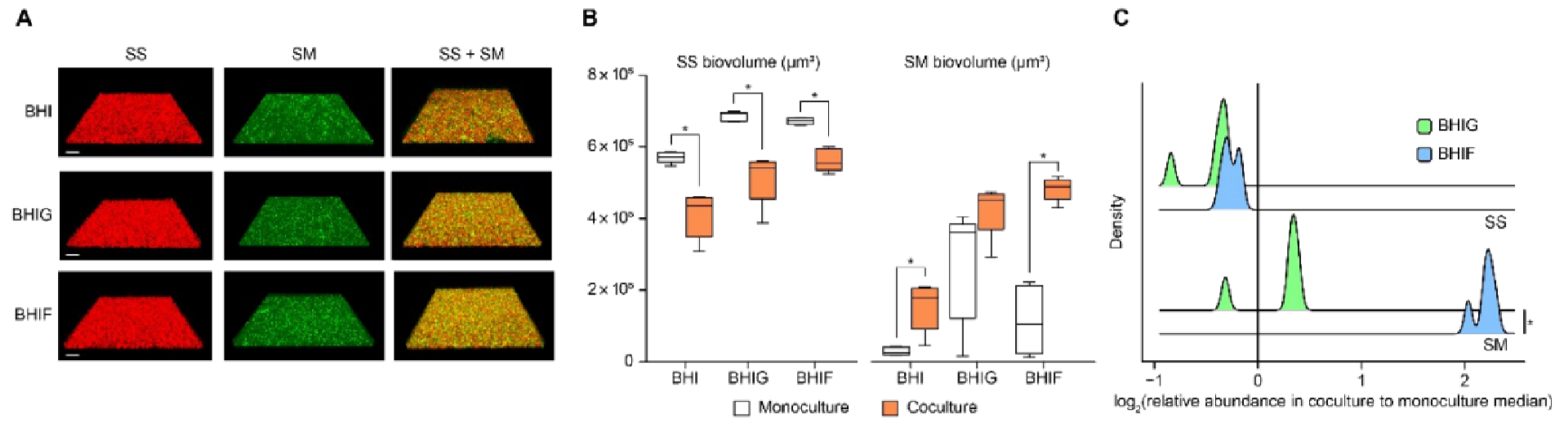

To confirm fructose’s role, scientists ran lab tests with two rival bacteria. One was Streptococcus mutans, which causes cavities. The other was Streptococcus sanguinis, which helps protect teeth.

When grown together, both sugars supported S. mutans. But fructose gave it a much stronger advantage than glucose.

Because many foods contain both sugars, this test explains why fructose becomes so harmful when it enters saliva from blood instead of from meals. A steady stream makes it easier for decay causing bacteria to dominate.

“This allowed us to understand the changes in these metabolites between the blood and saliva, and their subsequent changes after exposure to the oral microbiome,” Masae Kuboniwa, senior author of the study, said of the new saliva testing method.

Lead author Akito Sakanaka explained the biological shift. “The increase of these metabolites in saliva fueled changes in the oral microbiome, enriching cariogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans and reducing the abundance of health-associated species like Streptococcus sanguinis, shifting oral biofilm metabolism toward glycolysis and carbohydrate degradation,” he said.

Research findings are available online in the journal Microbiome.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post High blood sugar linked to cavity development in diabetics appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.