The classic thought experiment about a horse-sized duck and a hundred duck-sized horses is more than a joke. It captures a deep tradeoff between quantity and quality that shows up in nature, including in the tiny societies under your feet.

A new study shows that some ant species solved this tradeoff by going all in on numbers. Instead of building each worker as a heavily armored fortress, they invest less in individual protection and redirect those nutrients into making more ants.

That choice, the researchers found, did not doom those species. It paid off. Colonies with cheaper, less protected workers often became bigger and more evolutionarily successful.

“There’s this question in biology of what happens to individuals as societies they are in get more complex,” said senior author Evan Economo, chair of entomology at the University of Maryland. As societies scale up, individuals may no longer need to be fully self sufficient. The collective can cover many tasks that once fell on a lone organism.

Part of that shift, Economo said, is that individuals may become “cheaper,” easier to produce in bulk but less robust on their own. Until now, that idea had not been tested with large scale data from social insects.

Ants are perfect for this kind of question. Some species live in colonies of a few dozen workers. Others build supercolonies with millions. Yet all of them rely on the same basic body plan, wrapped in a hard outer layer called the cuticle.

The cuticle works like armor. It shields ants from predators, drying out and infection. It also supports muscles. That protective shell has a steep price, however. It needs nitrogen and minerals that can be scarce in many ecosystems. A thicker shell demands more nutrients. That cost limits how many workers a colony can afford to raise.

Lead author Arthur Matte, a zoology Ph.D. student at the University of Cambridge, and colleagues suspected a tradeoff. Colonies that pour resources into thick armor for each worker might end up smaller. Colonies that cut corners on cuticle could channel those savings into more workers.

“Ants are everywhere,” Matte said. “Yet the fundamental biological strategies which enabled their massive colonies and extraordinary diversification remain unclear.”

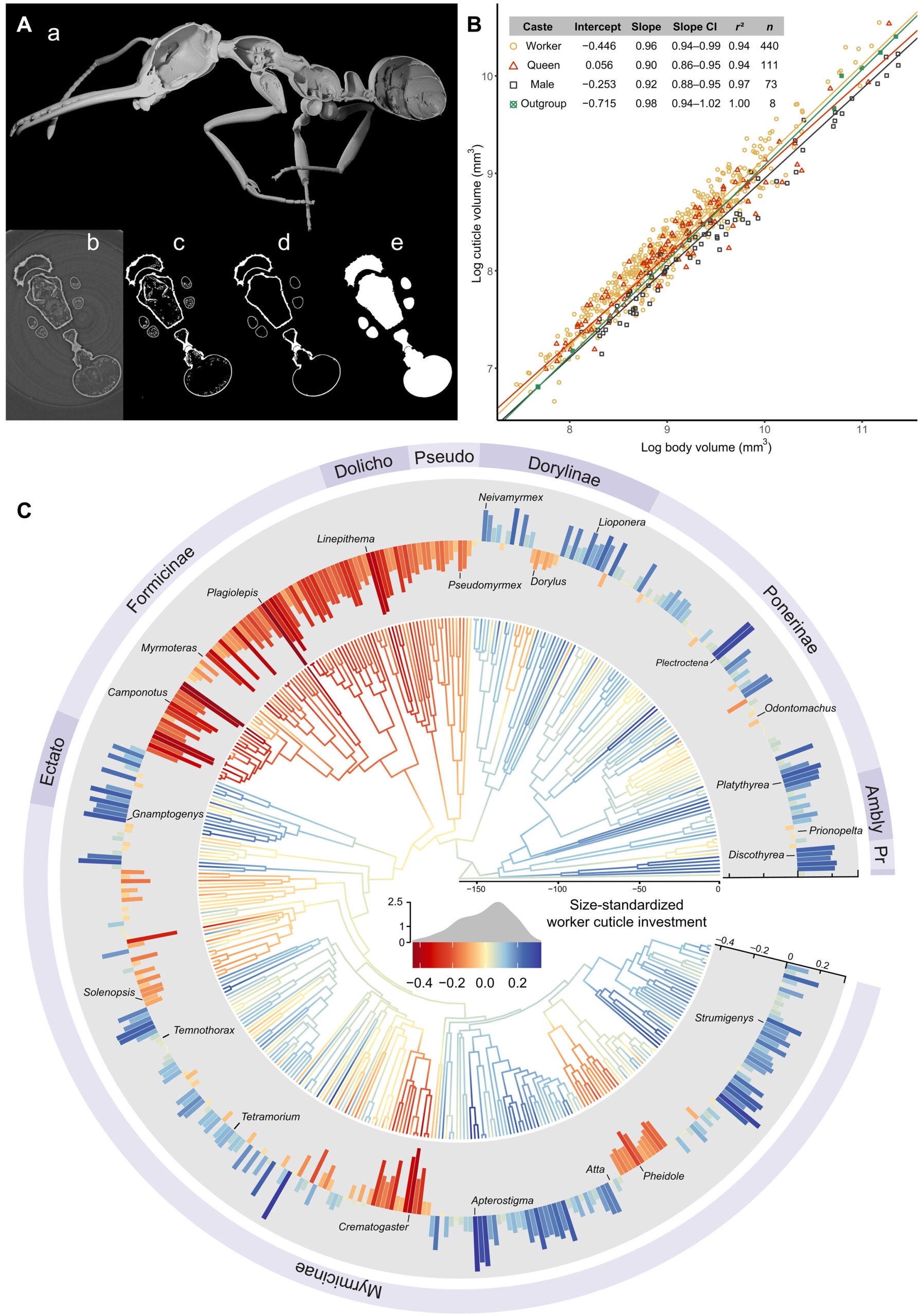

To test their idea, the team assembled a huge dataset built from 3D X ray scans. They measured body volume and cuticle volume for workers from more than 500 ant species.

The numbers varied widely. In some species, cuticle made up only about 6 percent of total body volume. In others, it reached roughly 35 percent. That difference represents a big range in how much each worker costs on a nutritional level.

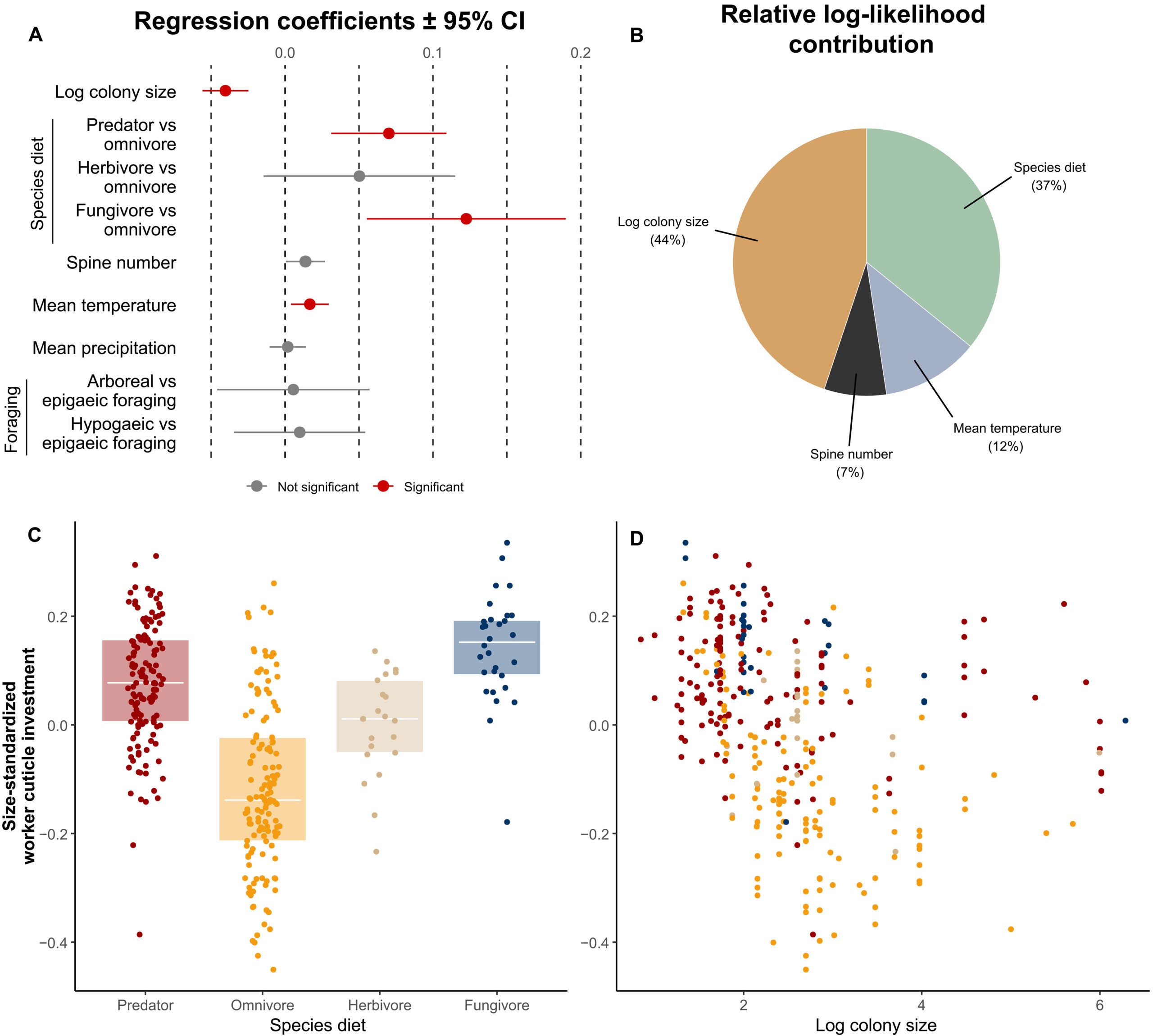

“Our research team combined these measurements with evolutionary models that included colony size and family tree information. A clear pattern appeared. Species that invested a smaller share of their body volume in cuticle tended to evolve larger colonies’,” Economo told The Brighter Side of News.

“In plain terms, when each ant is a bit “cheaper” to build, the colony can afford more of them,” he continued.

Thinner cuticles mean weaker personal armor. A single worker from one of those species might lose a one on one fight. Yet in a large colony, safety does not rest on a lone defender. It comes from coordinated behavior.

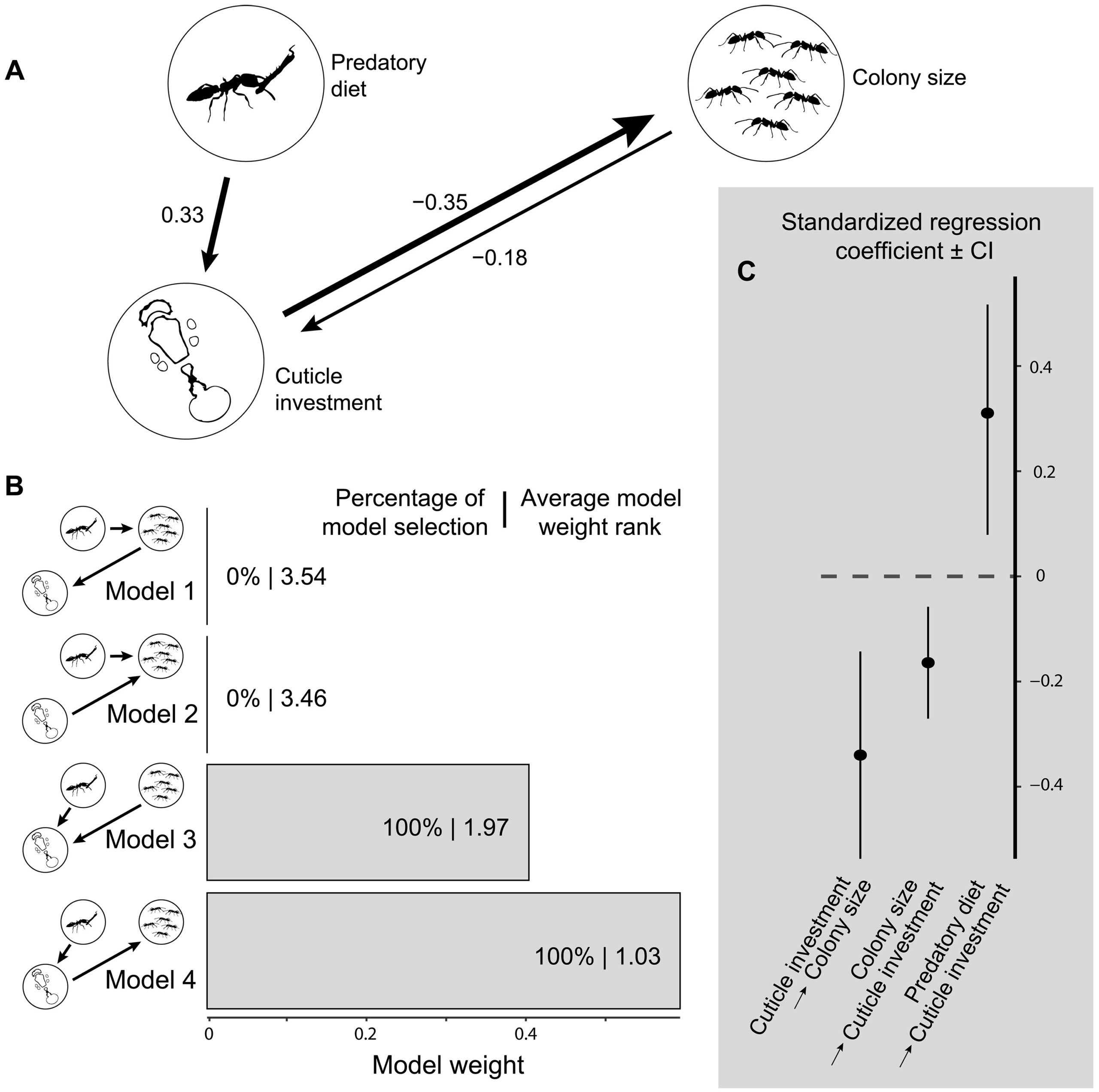

The authors suggest that reduced armor is part of a broader package of social traits. As colonies get larger, they evolve collective foraging, shared nest defense and strong division of labor. Group level protection can replace some of the security that a thick individual shell once provided.

“Ants reduce per worker investment in one of the most nutritionally expensive tissues for the good of the collective,” Matte said. The colony shifts from focusing on self protection toward a distributed workforce. That change supports more complex societies. Matte compared it to the evolution of multicellular life, where simple cells band together and gain new collective abilities.

Economo calls this shift “the evolution of squishability.” Many children, he joked, have already learned that some insects crush much more easily than others. Behind that playground observation lies a deep evolutionary story.

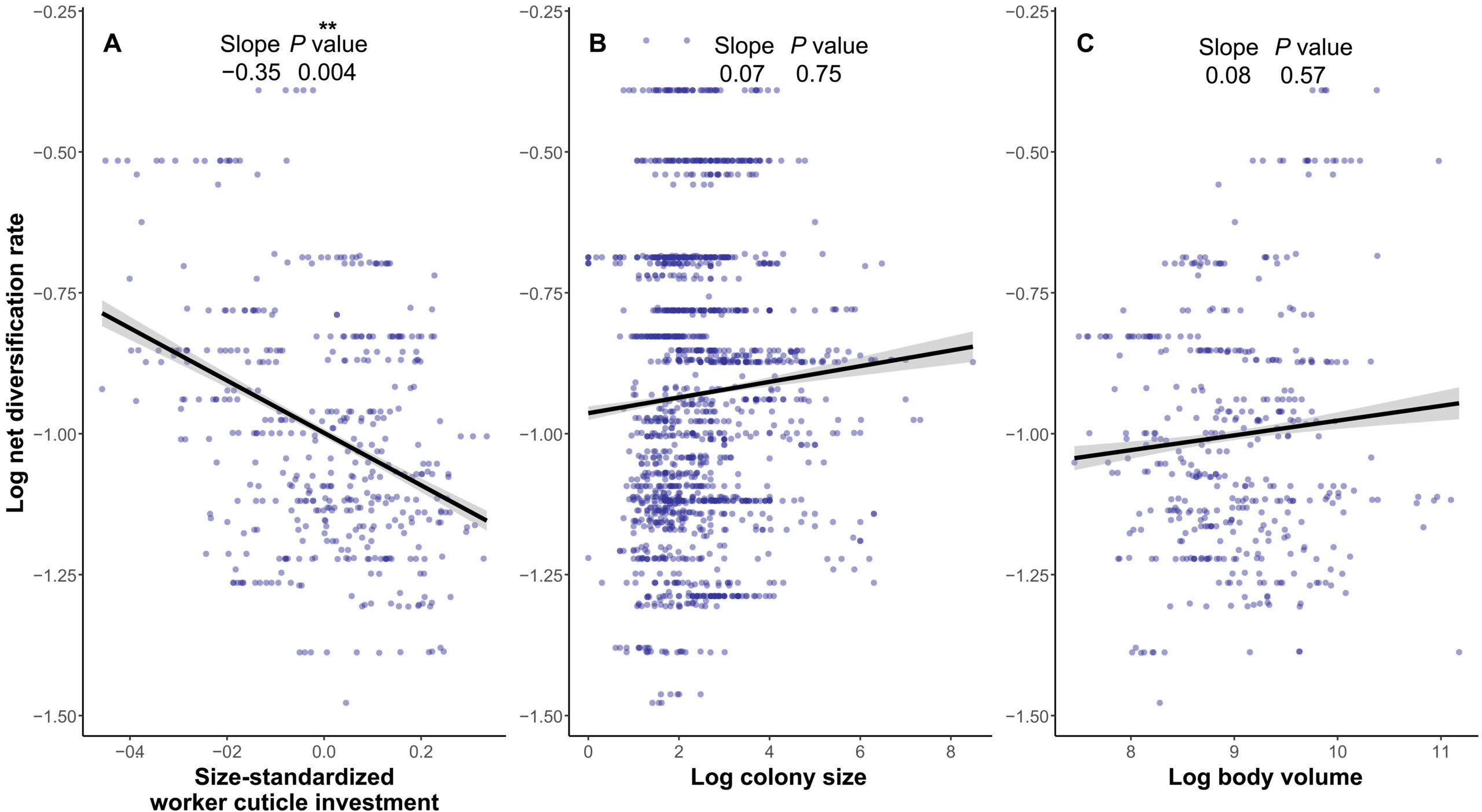

The team also looked at diversification rates, a measure of how often new species arise in a lineage. Here again, cheaper workers seemed to help. Lower cuticle investment was linked with higher diversification rates.

Not many traits have shown strong ties to diversification in ants, Economo noted. That makes this result stand out. It suggests that cutting per worker costs helped some ant lineages branch into many new forms.

Why might that happen. One idea is that cheaper bodies use less nitrogen and fewer minerals. Species that need fewer nutrients per worker may invade nutrient poor habitats more easily. That flexibility could help them spread, adapt and split into new species over time.

“Requiring less nitrogen could make them more versatile and able to conquer new environments,” Matte said. He began this work during a master’s internship in Economo’s lab at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan.

The study also proposes that complex social traits such as collective nest defense and disease management further lowered the need for heavy individual armor. Once group level protection improved, evolution could safely trim the cuticle. That change then supported even larger colonies, strengthening social defenses and feeding back into the same loop.

Ants are not the only social creatures that might follow this path. Termites and other social insects may have traded individual toughness for group size as well, though that still needs testing.

The work also resonates with human history. Economo points to shifts in warfare, where heavily armored knights eventually gave way to ranks of archers and other specialists. Mathematician Frederick Lanchester even wrote equations, Lanchester’s Laws, to explore the power of greater numbers versus stronger fighters.

“The tradeoff between quantity and quality is all around,” Matte said. “It’s in the food you eat, the books you read, the offspring you want to raise.” For him, tracing that tradeoff across ant evolution offered a rare view into how different lineages navigated their constraints and opportunities, ultimately producing the huge diversity of species we see today.

This study reveals how complex societies can arise when evolution tips the balance from individual robustness toward sheer numbers. For biology, it offers a framework to study other social organisms, from termites to cooperative vertebrates, and test whether similar quantity focused strategies shaped their histories.

Understanding how ants reduced per worker investment without collapsing their defenses may also inform new ideas in robotics, swarm algorithms and distributed systems. Engineers already look to ant colonies for inspiration on how large groups can solve problems without central control. Knowing that evolution favored “cheaper units” could guide designs that rely on many simple robots rather than a few advanced machines.

The link between lower cuticle investment and higher diversification hints at a broader rule. Organisms that reduce per individual resource demands may be better equipped to colonize harsh or nutrient poor environments. That insight could shape how ecologists think about resilience and expansion under climate change, when nutrient distributions and habitats are shifting.

Finally, the study gives a richer way to think about human systems. From staffing a hospital to structuring a military force, leaders often weigh quality against quantity. Ant evolution does not offer direct answers for people, but it does highlight how powerful group level traits become when individuals are built to serve the collective, not just themselves.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post How ants gave up armor to build some of the largest societies on Earth appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.