This article first appeared in Book Gossip, a newsletter about what we’re reading and what we actually think about it. Sign up here to get it in your inbox every month.

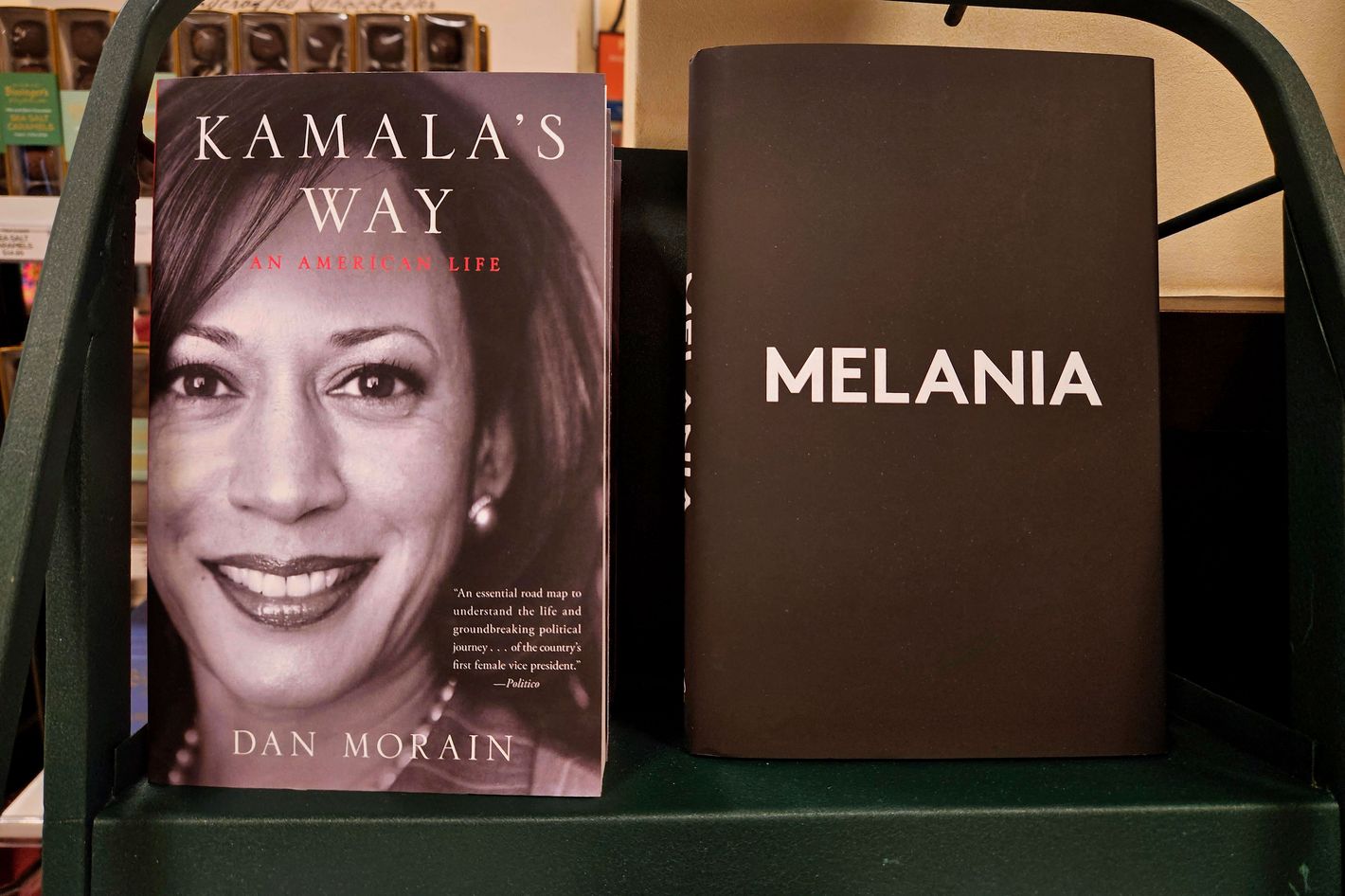

I wish there was a big pile of exciting new releases to dive into as a distraction right now, but it’s looking like publishers were right to move their schedules around to avoid the gaping maw of the election. What are we in for now? Will we see another round of liberal-resistance manuals and administration tell-alls, as we did during Trump’s first administration? Or will the people who make books go in new directions entirely? Early indicators show a healthy appetite for dystopian fiction: Not only did The Handmaid’s Tale claim the No. 2 spot on Amazon’s best-seller list in the days after the election, 1984 and Fahrenheit 451 also saw marked increases in their sales. On the other hand, so did Melania Trump’s memoir, J.D. Vance’s memoir, and RFK Jr.’s 2021 book about Anthony Fauci.

Two days after the election, Hachette announced the formation of a new imprint called Basic Liberty. It’ll be headed by Thomas Spence, a former publisher who is currently a senior adviser to the Heritage Foundation, the authors of Project 2025, which aims to classify much of what we think of as literature as pornography and ban it, among other things. This announcement angered Hachette employees, and one of them, editor Alex DiFrancesco, publicly resigned over it. On November 8, they announced on X that they had once felt the company stood behind their work on books on gender and sexuality. “After the formation of Basic Books’ Liberty Imprint,” they wrote, “I can no longer say I feel this way.”

When I spoke to DiFrancesco a week after they quit, they were sanguine about their decision. “They can claim to be a liberal and accepting company, but when they make decisions like this, they show that they really have their bottom line more in mind than anything like diversity and inclusion.” Earlier that same day, Publishers Weekly posted excerpts from an open letter from anonymous Hachette employees also deploring the new imprint: “We are calling on HBG to recognize the responsibility it has as one of the world’s leading publishers, to act with empathy and compassion for all people, and to reevaluate its decision to move forward with the creation of Basic Liberty and the hiring of Thomas Spence.” DiFrancesco applauded their efforts, but didn’t really think they’d get anywhere with that approach. “While people can write all the anonymous letters they want, I feel that if we’re going to take a stand, we actually have to put our names behind it.” When DiFrancesco took the job at a big-five house, they’d hoped it was possible to do good work from inside the system. Now, they’ve lost that illusion. “I honestly just don’t believe you can change things from the inside. So I hopefully will land at an independent press with good values.”

The marriage of art and capitalism in publishing has never been an entirely happy one, and conservative imprints — and, of course, conservative readers — are nothing new. What is new is the somewhat abrupt shift in what “conservative” means, or what it’s now acceptable to say out loud about what it means. Elsewhere in publishing, a VP of marketing at Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group raised eyebrows by posting a pro-Trump graphic to her Facebook, and Skyhorse Media — which published those aforementioned Melania and RFK Jr. books — congratulated Tulsi Gabbard on being nominated as director of national intelligence. The pro-Trump faction in book publishing may be small, but it does exist, and the overwhelmingly blue industry is being forced to reckon with it, often painfully.

Moving as glacially as publishing does, it’ll be a few seasons yet before we really start to see the effects of the election. An editor at a literary imprint of a big-five house said the vibe at a recent postelection meeting was vague, but focused on solidarity. “Supporting our most vulnerable authors as they publish into 2025 and beyond, and taking time to really appreciate the privilege we have as gatekeepers, and the importance of using that privilege in a climate of censorship. We didn’t discuss anything about, like, go find Trump books!” One agent told Politico they heard something similar from the editors they were in touch with. “No one has the energy to go through another four years of publishing this stuff even though the first four years were very good for publishers.” One author, who has a novel coming out next spring, said they were even a bit relieved that it didn’t seem like there would be much appetite for Trump books this time around. “In the run-up to the election, I’d been concerned — not as concerned about, you know, the state of the world, but concerned — that publishing a novel in the new Trump years would be tantamount to just letting it die,” they said. “While I wouldn’t say I’m remotely heartened by anything that’s happened since the election, I do now think it’s apparent that basically all of my friends are tuning out the news and looking for an escape, at least for now, and I think people will be reading more fiction and far fewer Trump books.”

Given that, what kind of books are agents thinking about representing and selling in the months to come? “This time, I’m more interested in what the left, and liberalism more broadly, can and should do,” one told me. “My hope is that we will once again see real intellectual curiosity about understanding our moment. My fear is we’ll drown in apathy or invest only in escapism, as it’s doing well now, at the expense of anything else.” Another agent foresees a rise in books that “solve problems” — whether that’s “traditional self-help” (maybe an echo of the self-care boom of the first Trump administration) “or books by big-picture visionaries.”

Then there are those who think things will get so bad they will eventually … get better. “I don’t think writers themselves realize how corporate and commercial and uniform all of big trade publishing has gotten,” says an agent who runs her own agency. “So I either see that happening even more, a continuation of the flattening and incuriosity of not just the industry side but of the art too. Or, a backlash, where we start to see an emergence of what made publishing fun pre-Trump.” We can always dream!

There does seem to be at least one person in publishing who’s benefiting from a second Trump term. Back in 2021, Trump set up his own publishing house, possibly to save himself the humiliation of potentially receiving a lower advance than Barack Obama on his post-presidential memoir. Sergio Gor, the man in charge of publishing Trump’s books, will now run the presidential personnel office in his administration.