Around 300,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa, a pivotal moment in human history. Yet, the roots of this lineage stretch much further back, over six million years, when the human lineage separated from chimpanzees and bonobos.

Despite significant progress in mapping human evolutionary history, understanding the ancient population size of early human ancestors remains elusive, particularly during the Pleistocene epoch.

Limited access to ancient DNA from African Homo specimens complicates efforts to explore these mysteries, leaving researchers dependent on present-day genomic data.

A groundbreaking study published in Science, addresses this challenge using a novel computational approach.

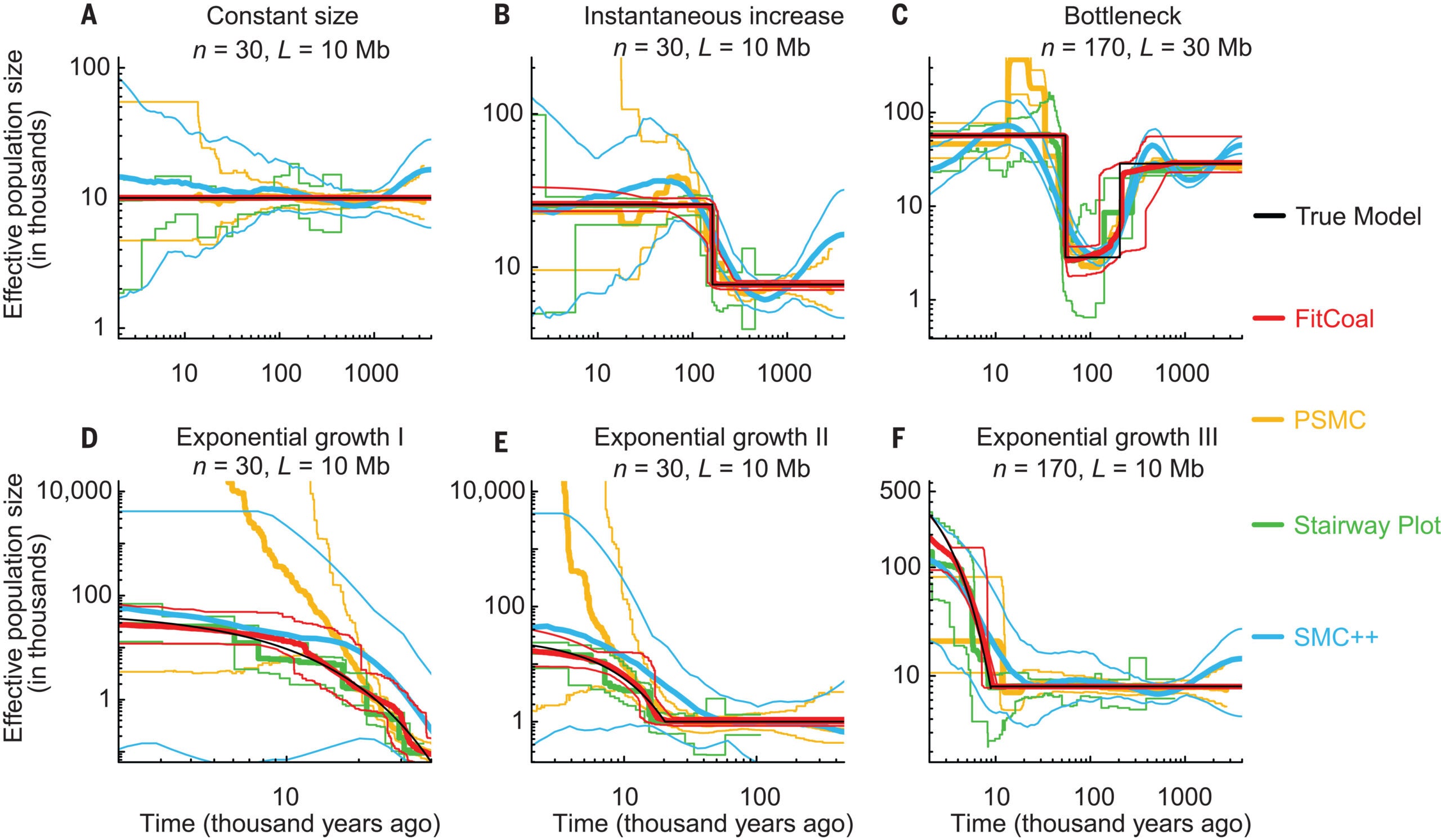

A team of researchers from China, Italy, and the United States employed a method called FitCoal (fast infinitesimal time coalescent process) to analyze modern human genomic data from 3,154 individuals.

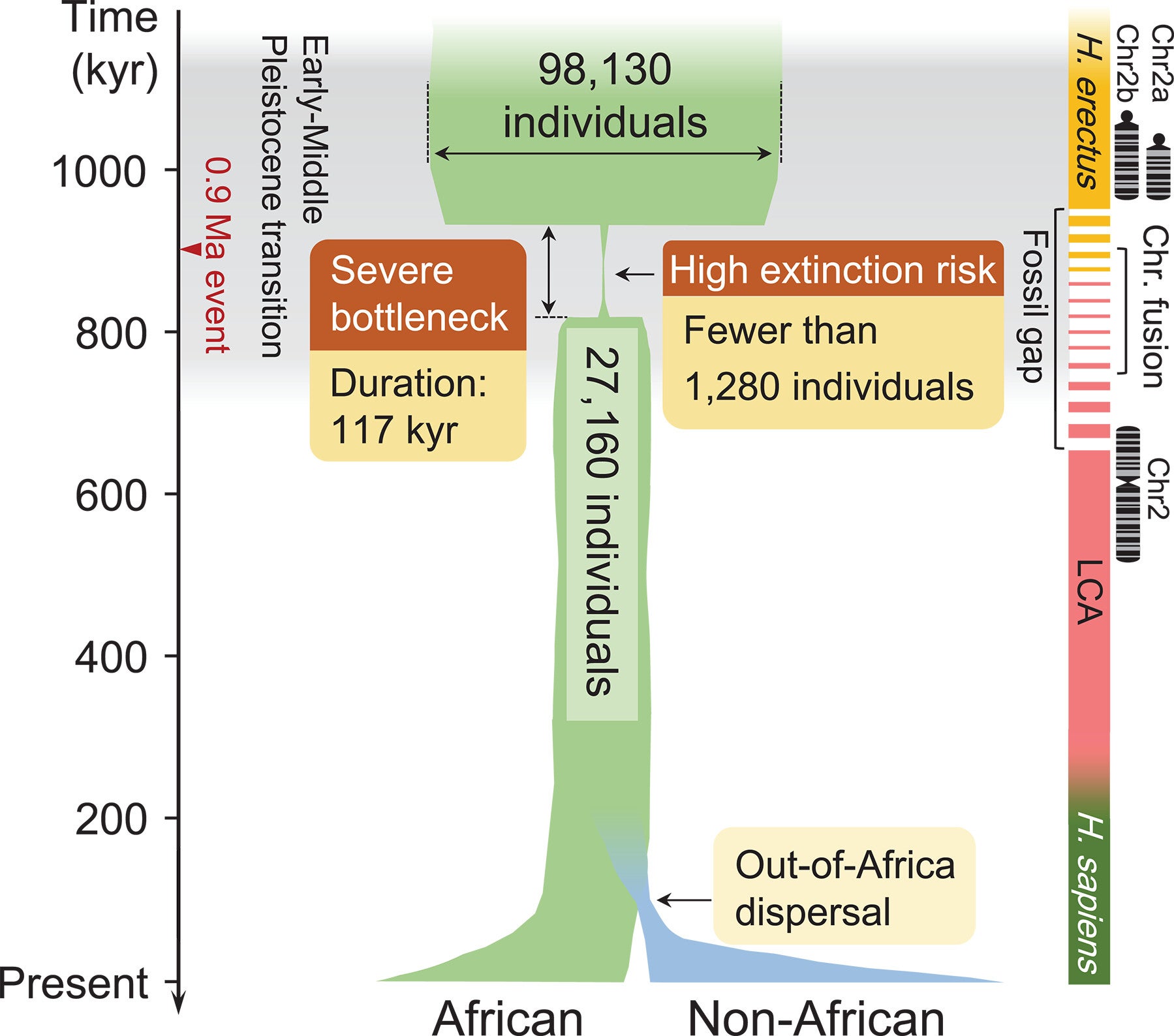

Their findings shed light on an ancient bottleneck that profoundly shaped human evolution, narrowing the population to approximately 1,280 breeding individuals for 117,000 years.

This severe bottleneck, occurring between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago, represents a period of drastic population decline. During this era, climatic upheavals, including glaciation events and severe droughts, dramatically altered ecosystems.

These conditions likely disrupted food sources and created harsh survival challenges. Senior author Giorgio Manzi, an anthropologist at Sapienza University of Rome, explains, “The gap in the African and Eurasian fossil records can be explained by this bottleneck in the Early Stone Age. Chronologically, it coincides with significant loss of fossil evidence.”

Related Stories

The effects of this population crisis were profound. An estimated 65.85% of current genetic diversity was lost during this period, threatening the survival of humanity as we know it.

However, the bottleneck also facilitated a key evolutionary event—the fusion of two ancestral chromosomes into what is now known as chromosome 2 in modern humans. This genetic shift potentially marked the divergence of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans.

Traditional methods for studying ancient population sizes often rely on formulas that struggle with accuracy due to numerical errors.

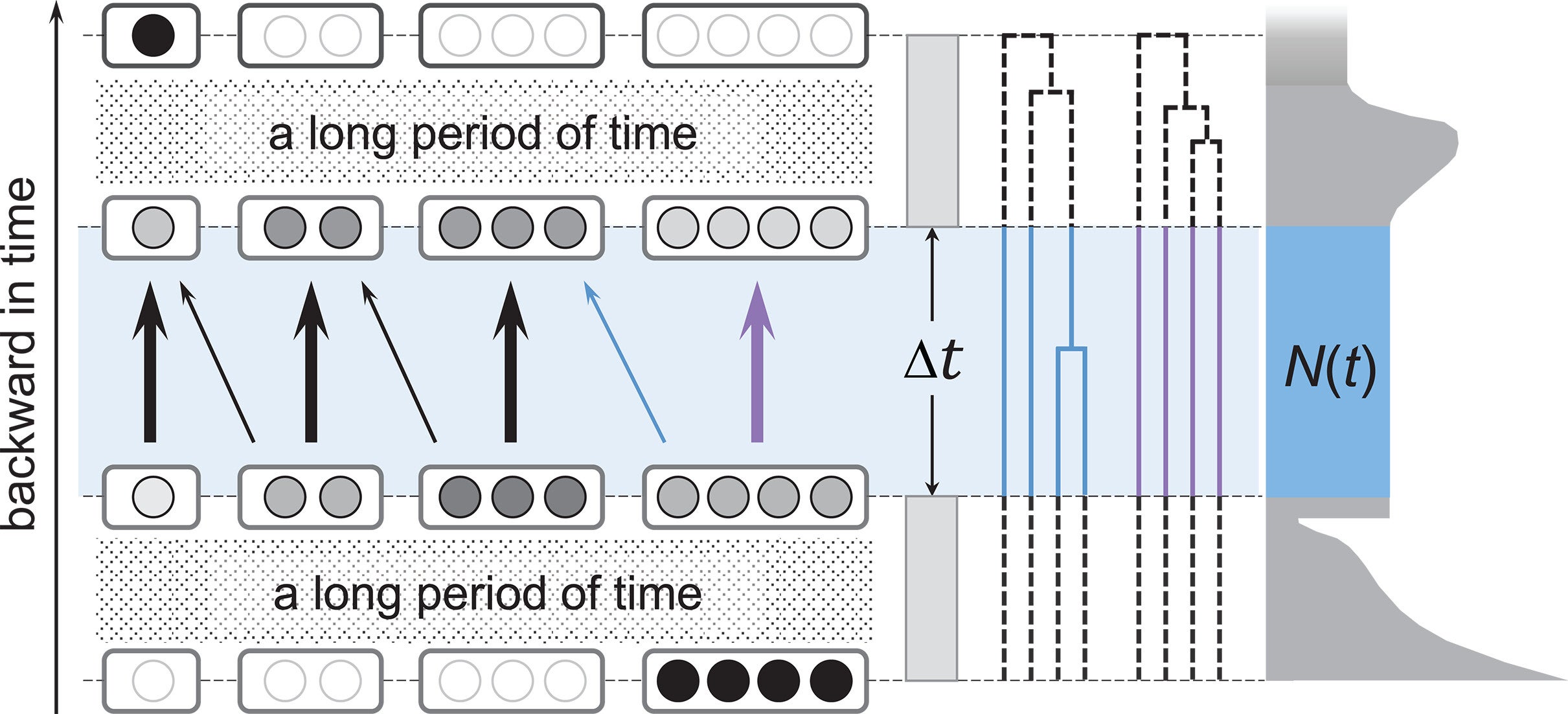

FitCoal overcomes these limitations, providing precise demographic inferences by analyzing the site frequency spectrum (SFS) of genomic sequences. SFS tracks the distribution of allele frequencies in present-day human genomes, preserving clues about ancient population changes.

“The fact that FitCoal can detect the ancient severe bottleneck with even a few sequences represents a breakthrough,” says senior author Yun-Xin Fu, a theoretical population geneticist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. This methodology not only illuminated the bottleneck but also paved the way for new questions about early human survival and adaptation.

The bottleneck period raises critical questions about how such a small population managed to endure and thrive. The control of fire and a gradual shift toward more hospitable climates may have played roles in sustaining this fragile group. Around 813,000 years ago, these factors likely contributed to a rapid population expansion.

Yi-Hsuan Pan, an evolutionary genomics expert at East China Normal University, highlights the implications of these findings. “The novel finding opens a new field in human evolution because it evokes many questions, such as the places where these individuals lived, how they overcame catastrophic climate changes, and whether natural selection during the bottleneck accelerated the evolution of the human brain.”

The research also underscores the importance of natural selection during this period. Environmental pressures may have driven adaptations that were pivotal to the development of traits distinguishing modern humans, including cognitive abilities.

While the discovery of this bottleneck offers crucial insights, it also raises new questions. Researchers aim to unravel the geographic locations of these early humans and the strategies they employed to survive. Further genomic analysis and archaeological investigations are necessary to build a more complete picture of human evolution during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition.

“These findings are just the start,” says senior author Li Haipeng, a computational biologist at the Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health. “Future goals with this knowledge aim to paint a more complete picture of human evolution during this period, unraveling the mystery that is early human ancestry and evolution.”

This research bridges significant gaps in the fossil record and offers a deeper understanding of how climatic events and genetic bottlenecks shaped the path of human evolution.

By revealing a critical chapter in our past, it provides a foundation for future studies that could uncover even more about our species’ origins.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Humans almost went extinct 930,000 years ago, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.