When your body senses something is wrong—whether it’s a damaged cell or a growing tumor—it can react in many ways. One of the most powerful is cellular senescence.

This process stops a cell from multiplying and releases a burst of warning signals to your immune system. It’s like pulling a fire alarm inside your body, and for cancer researchers, it’s becoming one of the most exciting tools in the fight against tumors.

Cellular senescence acts like a built-in defense system. When a cell becomes too damaged to function, it shuts down its ability to divide. But it doesn’t go quietly. It starts producing a mix of proinflammatory signals, collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype, or SASP.

These signals are not random. They serve a purpose: to alert the immune system and call in backup. That backup includes immune cells like macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, which specialize in removing troublemakers.

This stress response helps maintain healthy tissue. But things become more complex in cancer, where senescence takes on a double role. While it can slow tumor growth by halting the spread of damaged cancer cells, it can also create an environment that either helps or hinders immune attack, depending on the situation.

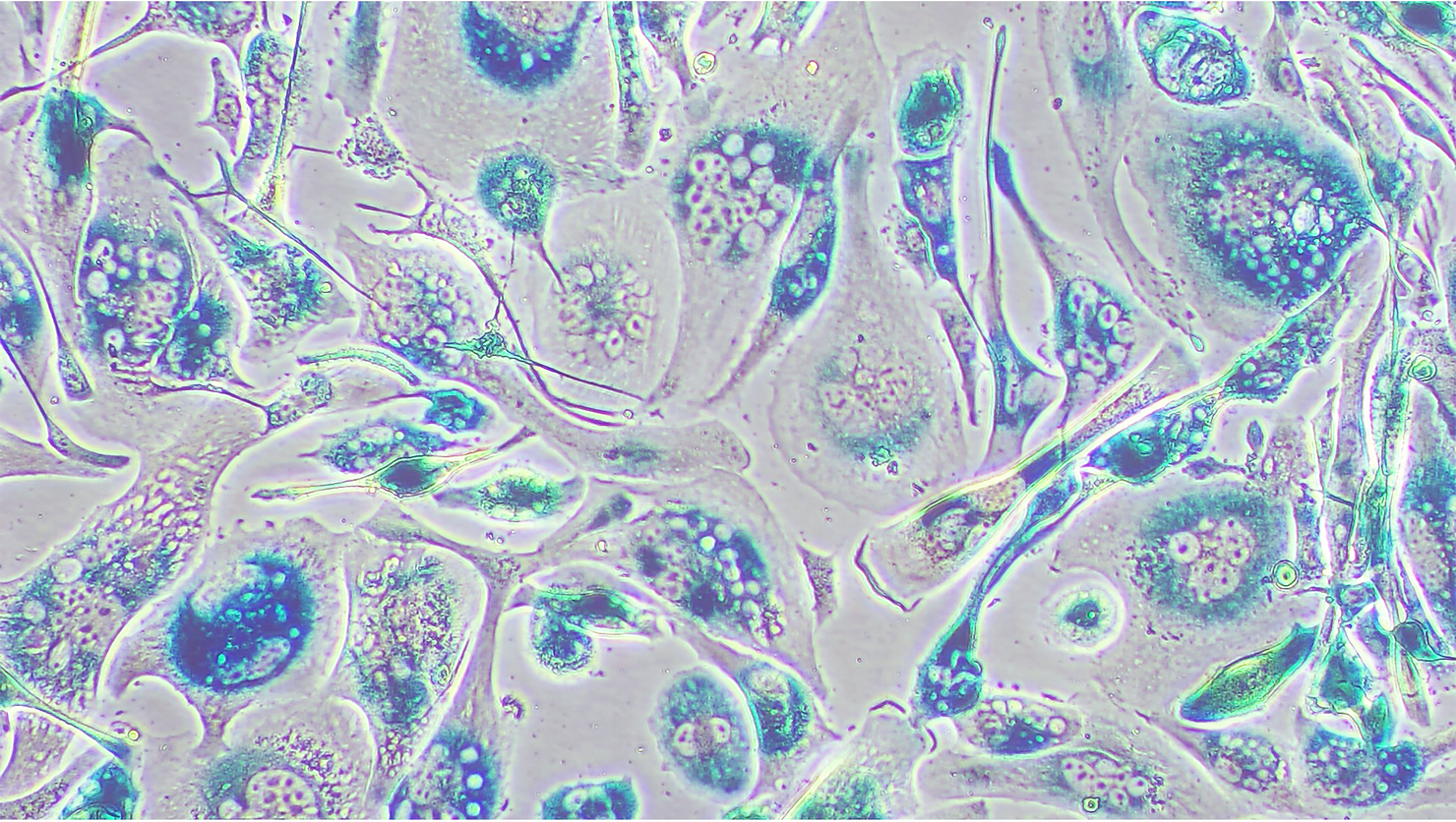

Cancer cells live in stressful conditions. They face a constant barrage of challenges—from low oxygen and faulty genes to harsh treatments like radiation or chemotherapy. Any of these can push them into senescence. As a result, tumors—before and after treatment—often contain a mix of both dividing and senescent cells.

Related Stories

While senescent cells don’t grow or spread, they’re far from passive. Their SASP activity changes the tumor environment, influencing how other cells behave. In some cases, SASP attracts powerful immune cells, including CD4 and CD8 T cells, which are crucial for killing cancer. But in other cases, it may do the opposite, making tumors harder to fight.

The exact outcome depends on factors like the type of cancer, the treatment used, and the timing of senescence. Still, one thing is clear: senescent cells can play a key role in shaping the body’s immune response to cancer.

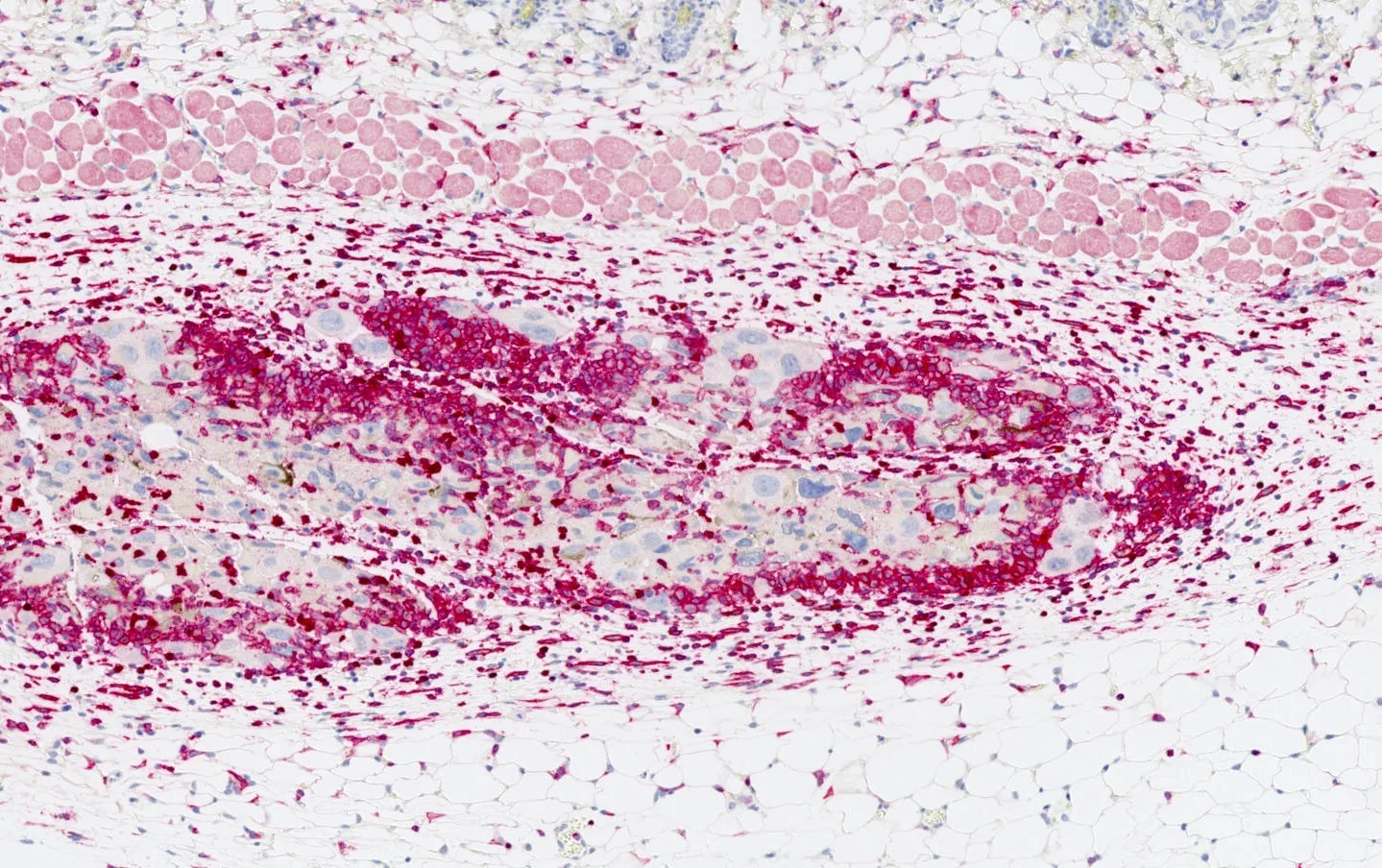

Scientists have long known that senescent cells are targeted by innate immune cells—your body’s first line of defense. These include macrophages, NK cells, and even specialized types like iNKT cells and neutrophils. They’re like the emergency responders, showing up quickly when senescent cells cry for help.

But what about the adaptive immune system, which provides long-term and highly specific defense? There, the picture is less complete, but recent research is filling in the blanks.

One study showed that in mice, senescent liver cells with a cancer-causing mutation were able to activate CD4 T cells. These T cells then directed macrophages to eliminate potentially harmful cells. Another study found that senescent skin cells expressed molecules recognized by CD8 T cells, but only under certain conditions.

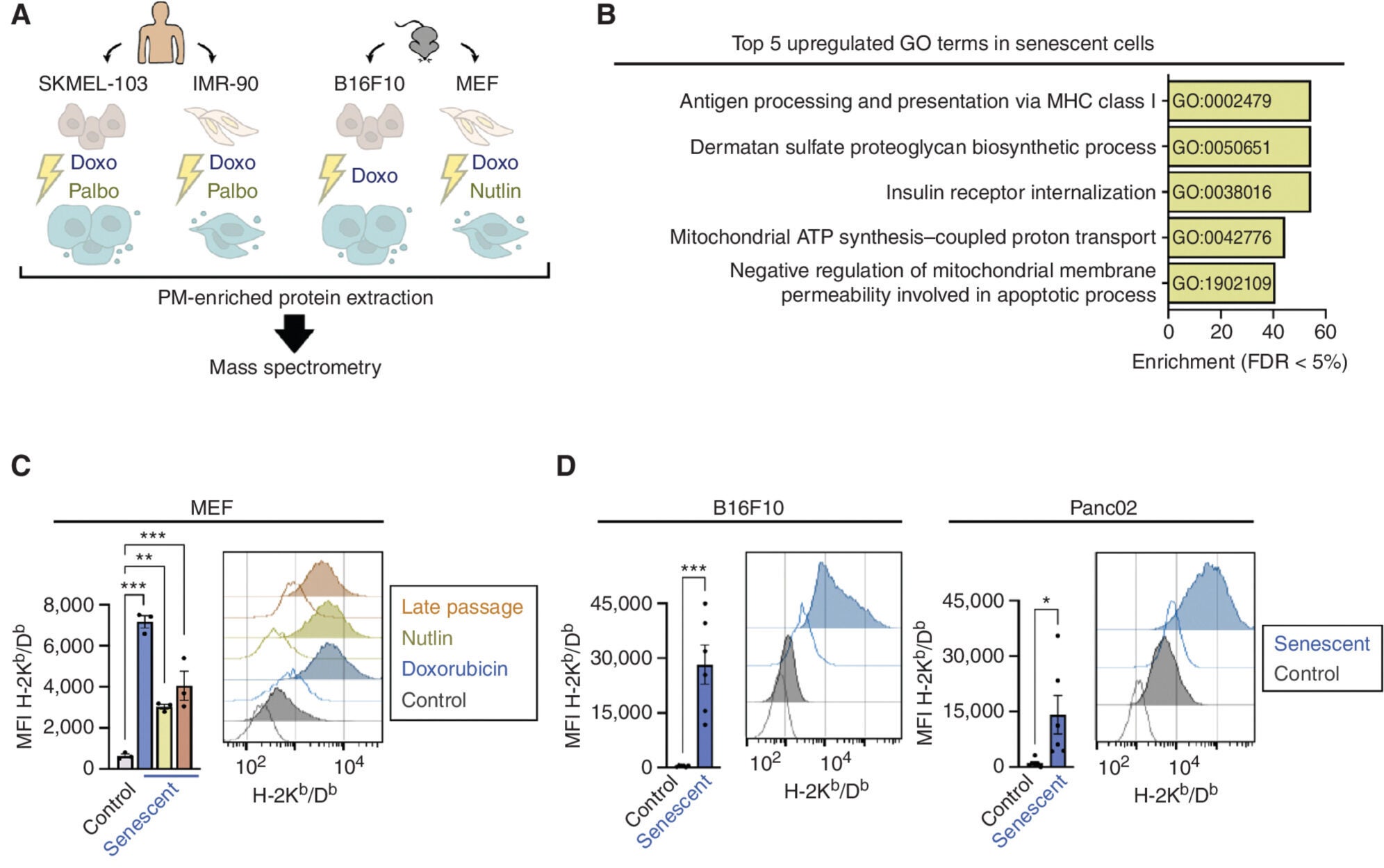

What’s especially intriguing is the discovery that senescent cells can express both warning signals and shields. They may increase markers like MHC class I, which help alert CD8 T cells, while also boosting levels of HLA-E—a molecule that acts like a “do not attack” sign to immune cells. This back-and-forth shows how complex and fine-tuned the immune relationship with senescent cells really is.

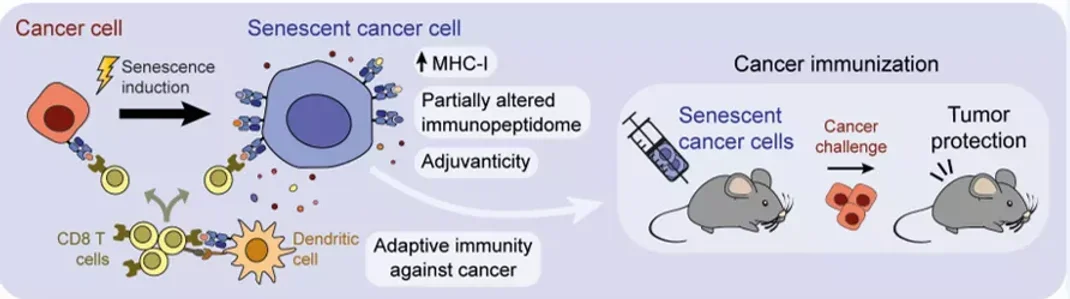

A groundbreaking study from researchers at IRB Barcelona is now pushing this science into new territory. Their team, led by Dr. Manuel Serrano and Dr. Federico Pietrocola, found that senescent cancer cells could actually serve as powerful cancer vaccines.

In experiments with mice, researchers used senescent cancer cells to trigger an immune response. When healthy mice were injected with these cells, they gained strong protection against future tumors. Even mice that already had tumors showed moderate improvements. This approach worked not just in immune-sensitive cancers like melanoma, but also in more resistant types like pancreatic cancer.

“Our results indicate that senescent cells are a preferred option when it comes to stimulating the immune system against cancer,” explained Dr. Serrano.

Why does it work? For one, senescent cells don’t disappear quickly. Unlike dead cells, which are cleared out fast, senescent cells stay active for a while. This gives the immune system more time to respond. Also, since they don’t divide, they don’t pose a risk of creating new tumors. It’s a safe way to “train” your immune system using cells that resemble the enemy but can’t grow or spread.

Even human cancer cells, when forced into senescence, became better at activating the body’s own CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes—cells that directly attack cancer.

This research doesn’t stand alone. A team at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, led by Dr. Direna Alonso-Curbelo and Dr. Scott W. Lowe, also found that senescent tumor cells change in ways that make them easier for the immune system to spot and destroy.

“Senescence increases the ability of cells to receive signals from their environment that activate pathways for recognition and destruction by cytotoxic T cells,” said Dr. Alonso-Curbelo.

In other words, senescent cells are not just sending out distress calls—they’re also becoming more sensitive to incoming immune instructions. That opens the door for combining senescence-based vaccines with other treatments like checkpoint inhibitors or CAR-T cells. Together, they might offer a more complete and lasting immune defense.

The IRB Barcelona team worked with collaborators from Canada and the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology. Their joint efforts show that this approach could work across a wide range of cancers and could one day be used alongside existing immunotherapies.

Of course, this is still early-stage science. Senescence is a powerful tool, but it needs to be controlled carefully. Too much inflammation from SASP could harm nearby tissues or cause immune overreaction. Also, not all senescent cells behave the same way. Some may resist immune attack using proteins like HLA-E or by releasing immunosuppressive molecules.

But these challenges aren’t deal-breakers. They’re part of the learning process. What’s important is that researchers are now seeing senescent cells as more than just dead weight. They may become key players in next-generation cancer therapies.

The concept of turning a cell’s final act into a therapeutic trigger is bold—and it’s gaining traction. Future treatments could include vaccines made from senescent cells tailored to your specific cancer. Or you might receive a combined treatment where senescence is first induced in tumor cells, followed by immune activation. This strategy could even extend to age-related diseases like atherosclerosis, where senescent cells also build up and cause harm.

For now, scientists continue to study the many signals involved in senescence and immunity. Each discovery brings us closer to treatments that don’t just slow cancer down—but help your own body destroy it completely.

The research findings are available within the journal Cancer Discovery.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Lifesaving new vaccine protects against multiple types of cancer appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.