Living organisms quietly emit light. This glow is real, measurable, and tied to life itself. Researchers at the University of Calgary and the National Research Council of Canada have now shown that this ultraweak light fades sharply after death, offering new insight into the chemistry that separates living tissue from lifeless matter.

The research was led by physicists Dr. Daniel Oblak and Dr. Christoph Simon from the University of Calgary’s Department of Physics and Astronomy. The team collaborated with scientists at the National Research Council Canada’s Human Health Therapeutics Research Centre in Ottawa to image faint light emissions from plants and mice.

“I suppose it has a little to do with people being reminded of auras,” Simon says. “It is a fact that living beings glow. It’s a very weak glow, but it’s there and visible with very sensitive cameras.”

This light, known as ultraweak photon emission, or UPE, cannot be seen by the human eye. It arises from normal chemical activity inside cells, especially reactions involving reactive oxygen species, or ROS. These molecules appear when cells respond to stress from toxins, infection, injury, or imbalance.

When ROS levels rise beyond what cells can control, oxidative stress sets in. That process damages fats and proteins inside cells. As molecules break apart and reform, electrons briefly enter excited states and release tiny packets of light when they settle back down. Those photons make up UPE.

Because ROS and oxidative stress are linked to disease, scientists have long wondered whether this faint glow could act as an early biological signal.

Spontaneous light from living tissue does not require an external source. Even after hours in complete darkness, organisms continue to emit UPE due to internal chemistry and body temperature.

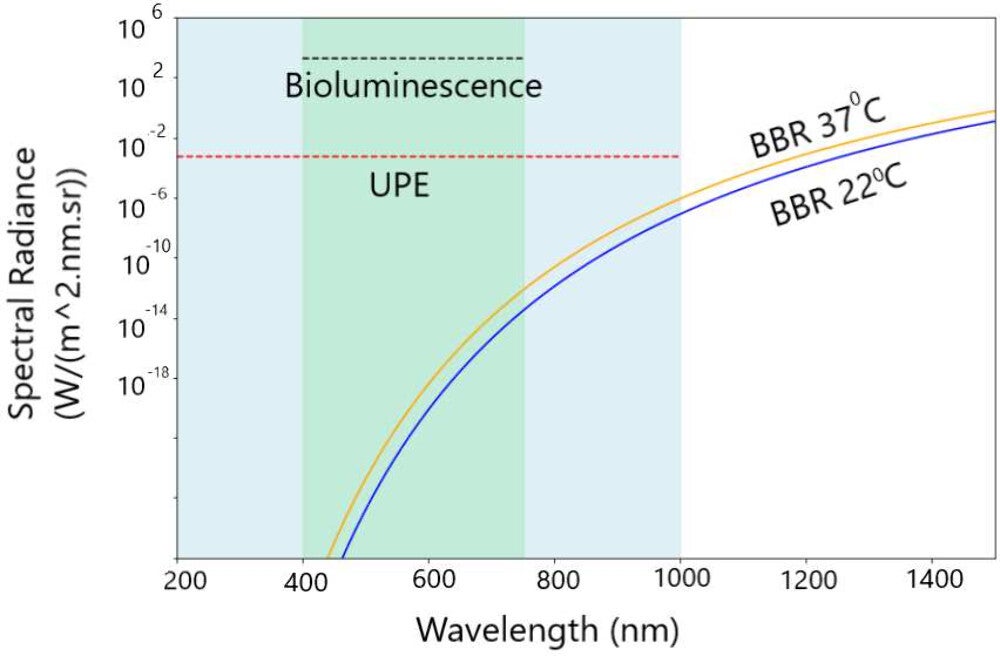

“Scientists typically group spontaneous emission into three categories. Blackbody radiation is thermal glow that all objects produce. At body temperature, its intensity in visible and near-infrared light is extremely low. Bioluminescence, by contrast, is bright and purposeful, as seen in fireflies and glowing marine life,” Oblak explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“UPE sits between these extremes. It spans ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths and comes from everyday metabolic reactions. Unlike thermal radiation, it changes with biological activity and chemical stress,” he continued.

“Calculations show that below about 1,200 nanometers, UPE is far stronger than thermal radiation at room or body temperature. That means heat-based light can be ignored when imaging UPE with modern detectors,” he said.

Detecting such weak light requires specialized equipment. Early studies relied on photomultiplier tubes with limited image detail. This work used advanced digital cameras capable of detecting single photons with high spatial resolution.

Plant experiments at the University of Calgary used an electron-multiplying CCD camera housed in a dark tent. The sensor was cooled to minus 95 degrees Celsius to reduce background noise. Researchers adjusted pixel binning and gain to improve signal clarity while keeping raw photon counts intact.

Mouse imaging took place at the National Research Council Canada using a separate low-noise CCD system inside ultradark enclosures. No image-processing filters were applied. Instead, color scales were adjusted only to improve contrast.

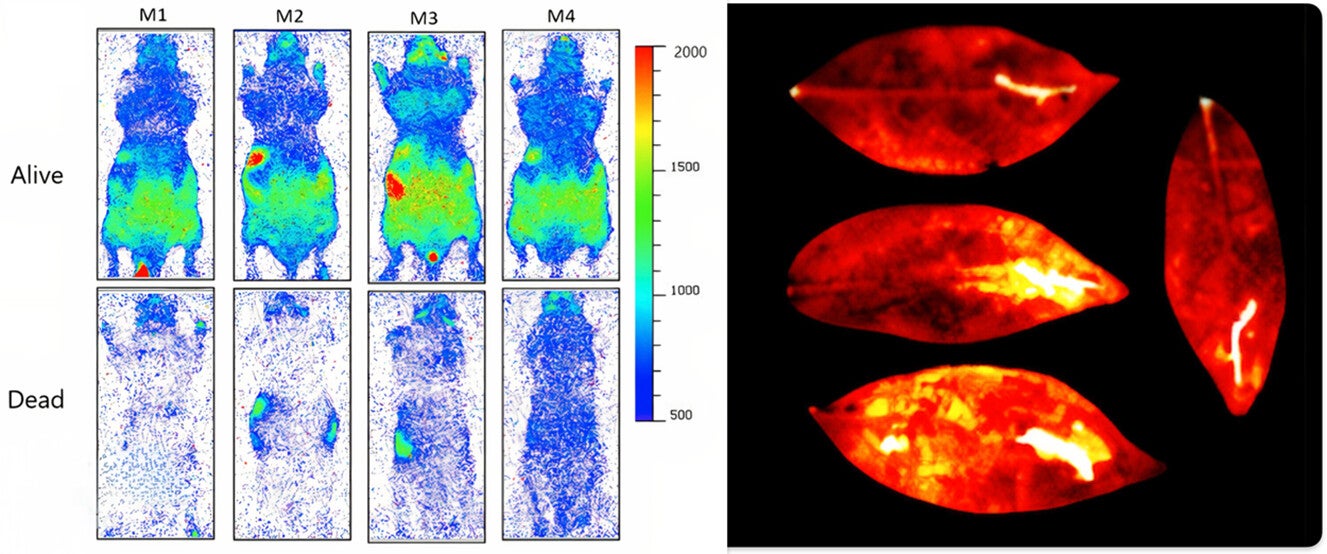

To test whether UPE reflects life itself, the team imaged hairless mice before and after death. Each mouse was anesthetized and allowed to adapt to darkness before imaging. Afterward, the same animals were euthanized and returned to the imager under identical conditions.

The difference was stark. Living mice emitted far more light across their bodies than they did after death. Statistical tests confirmed the drop was significant.

Temperature could not explain the change. Both living and dead mice were held at 37 degrees Celsius. Anesthetic effects were also unlikely to account for the sharp decline.

“We saw that the level of light that they emit, this biophoton glow, is distinctly different between living and dead animals,” Oblak says.

The simplest explanation was the loss of active metabolism. Once biochemical reactions stop, the glow fades.

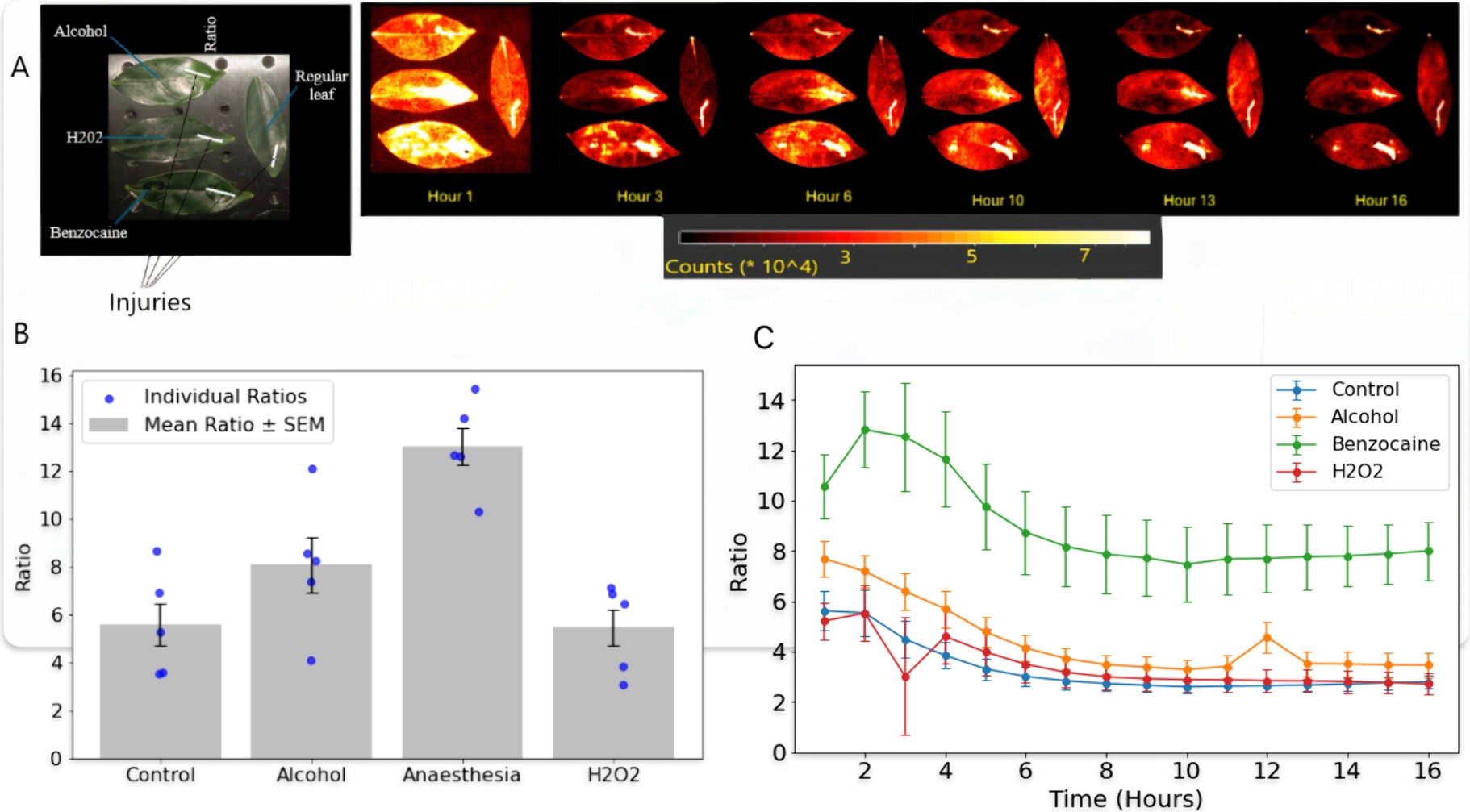

Plants offered another window into how UPE tracks biological activity. Researchers imaged living Arabidopsis plants and freshly cut leaves from Heptapleurum arboricola under different temperatures.

As temperature rose, photon emission increased. Warmer conditions sped up metabolism and ROS-related reactions. Beyond about 36 degrees Celsius, the glow declined, likely due to heat damage disrupting normal cellular processes.

Injury produced its own signal. Cut regions of leaves consistently glowed brighter than uninjured areas for hours.

Chemical treatments revealed an unexpected effect. Leaves treated with benzocaine, a local anesthetic, showed the strongest photon emission at injury sites, even exceeding the response to hydrogen peroxide. The reason remains unclear, but plant sodium channels may play a role.

The findings suggest that UPE reflects core biological activity. Living systems glow more than dead ones. Stress, injury, and chemical disruption all leave measurable light signatures.

“It’s a very small amount and it’s, of course, very tricky to detect,” Oblak says. “We must understand what that is to figure out what’s happening.”

While the glow may evoke mystical ideas, the researchers stress its physical origin. “It’s a biochemical phenomenon rather than a metaphysical one,” Oblak says.

Ultraweak photon emission offers a non-invasive way to study living systems without dyes or labels. In plants, it could help monitor crop stress, growth, and damage in real time.

In biomedical research, UPE imaging may provide early clues about tissue health, injury, or disease before symptoms appear.

With further development, this technique could support diagnostics by revealing subtle metabolic changes linked to stress and illness.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Physical Chemistry.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Living plants and animals emit a faint glow that fades after death appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.