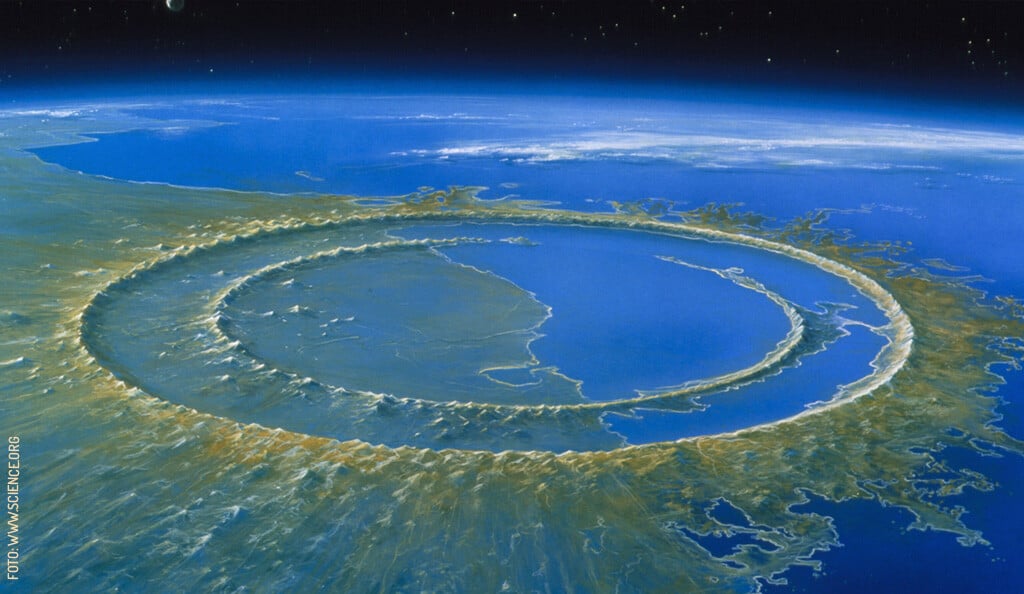

The impact of the asteroid 66 million years ago did not stop life from returning to normal for very long. New research shows that life, particularly marine life, recovered much more quickly than previously thought. New genera of plankton began to appear within thousands of years after the event.

Chris Lowery, an associate research professor at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics in the Jackson School of Geosciences, conducted this study in a way that allowed for the investigation of a critical point in Earth’s history, the aftermath of the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period. After that, life underwent a re-organization of ecosystems globally.

Prior to this research, scientists believed it would take tens of thousands of years for marine species to evolve following this catastrophic event. However, based on this new information, the first indication of a new evolutionary process took place significantly earlier than originally thought. It was within a time frame that belies what has been viewed as fact up to this point concerning how life responds to extreme global fluctuations in climate.

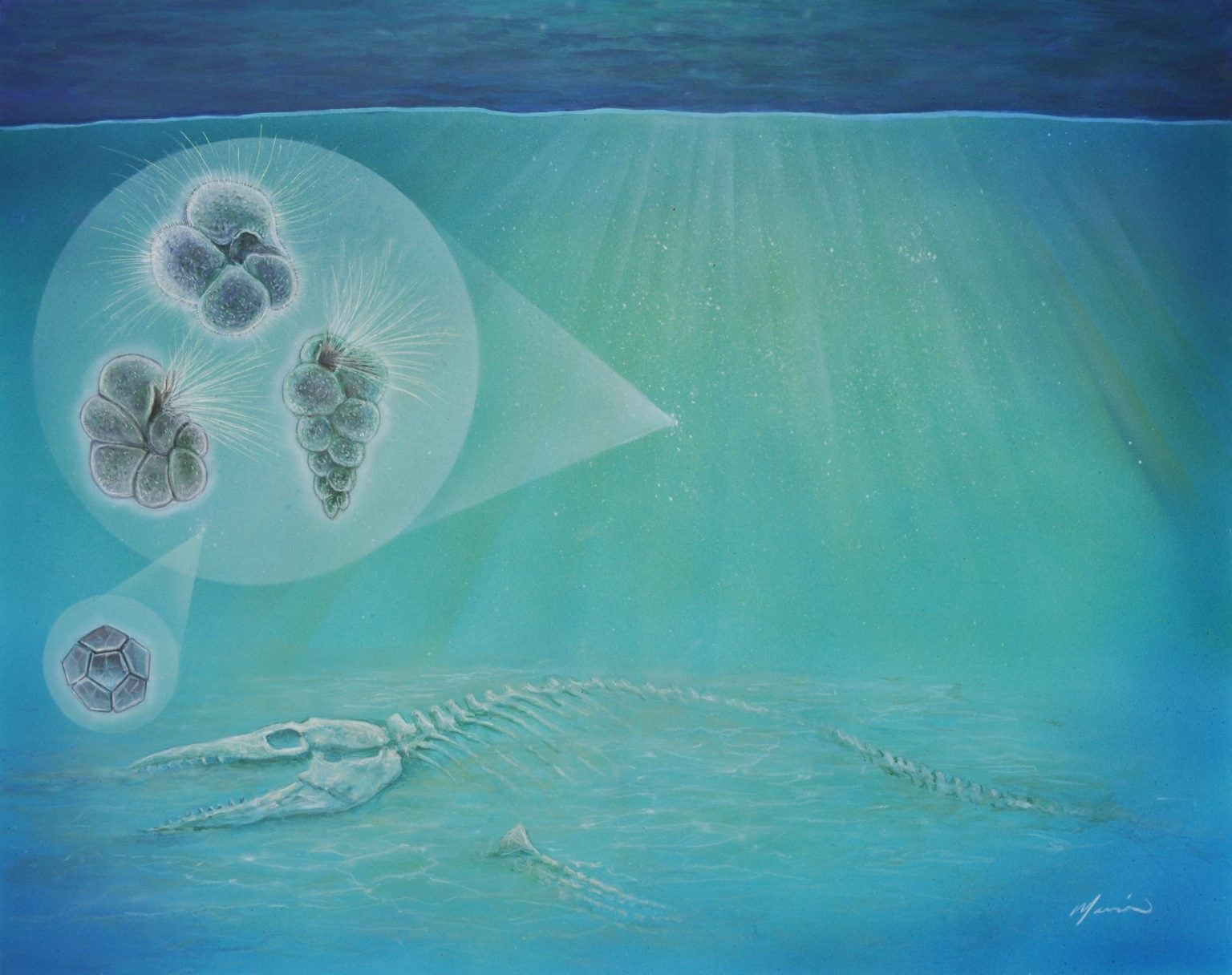

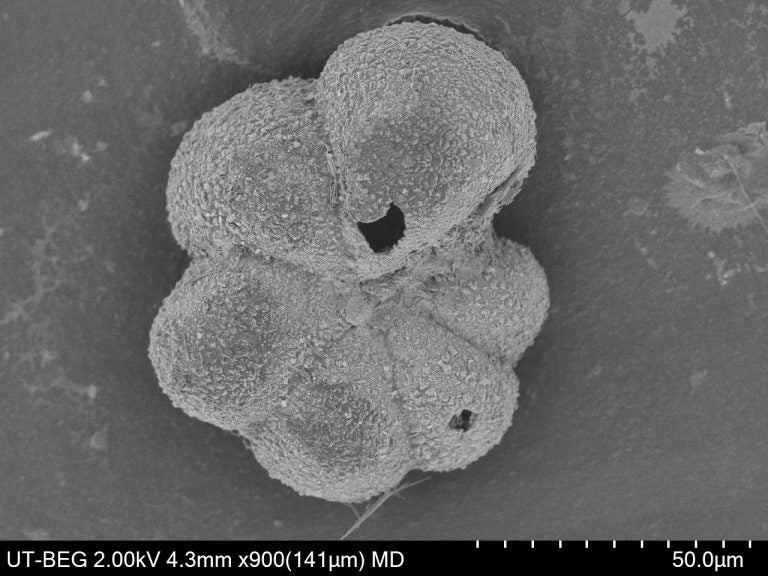

According to Lowery, “This study will provide a better understanding of the speed at which new species or genera can evolve and therefore the rate of environmental recovery from the Chicxulub impact.” Scientists have found a new marker for the beginning of the P0 biozone in the fossil record, the first occurrence of a tiny marine organism known as Parvularugoglobigerina eugubina. This type of plankton is part of a group called foraminifera.

Previously, it was thought that the top of the P0 biozone occurred approximately 30,000 years after the impact event. This date was based on a major assumption that sediments were deposited at a relatively uniform rate both before and after the extinction event.

Lowery and colleagues argue that this assumption cannot be supported by the fossil record.

“Mass extinction changed the ocean and the land. The loss of most calcareous plankton caused the cessation of the continuous accumulation of shells on the seafloor. The loss of vegetation led to increased soil erosion, leading to the introduction of sediments into the ocean. Both of these changes altered how sediments accumulated over time,” Lowery told The Brighter Side of News.

“You can’t just measure the thickness of sediment and assume the amount of time it took to accumulate. After the impact event, the clock is no longer running,” he added.

To determine how long it took to accumulate sediments after the impact, the researchers looked at the element helium-3. Helium-3 is formed when cosmic dust enters the Earth’s atmosphere and falls into the ocean at a relatively constant rate. The amount of helium-3 contained in the sediments does not depend on environmental conditions such as the rate of sediment accumulation.

As sediment accumulates slowly, the amount of helium-3 in the sediments increases. Conversely, sediments that accumulate quickly contain a lower ratio of helium-3. By determining the amount of helium-3 present in a sediment core, scientists can estimate approximately how much time has passed since sediments formed.

By employing published helium-3 datasets from six locations across Europe, North Africa, and the Gulf of Mexico, all containing evidence of the K–Pg boundary, the team was able to develop an overall picture of the conditions that existed in the world immediately after impact. Thus, they were able to recalibrate the timing of Zone P0 and the emergence of early Paleocene fauna.

The results indicate that Zone P0 lasted approximately 3,500 to 11,100 years, with an average of approximately 6,400 years. This duration is much shorter than had previously been established.

The new timeline culminates in an extraordinary amount of new information regarding the adaptive radiation, or evolution, of marine organisms following the Chicxulub impact event. Many of the newly identified planktonic species have been observed to have originated on Earth, meaning they evolved from existing species, within 2,000 years of the Chicxulub impact. Although it is currently uncertain how many of these planktonic species will be classified as new, meaning separate from existing species, there may be as many as 10 different plankton species that evolved exclusively within the confines of Zone P0.

The order of first appearances and exact timing of the first appearances of each planktonic species are not indicative of the pattern of the origin of those same plankton species on a global scale. This finding implies that distinct lineages of plankton species existed in separate geographic areas prior to migrating and diversifying across the world’s oceans.

According to Lowery, the rapid nature of the evolution of planktonic organisms has never before been documented in the fossil record. Normally, new species are documented as appearing within the fossil record over a span of hundreds of thousands or even millions of years. This study demonstrates that species that had previously existed on Earth were capable of generational diversification within a very small geological time frame.

The study’s results, however, build upon earlier research by Lowery and others that showed that life returned to the Chicxulub crater area in a relatively short time after the event. The current study extends this to show that, in addition to simply surviving, the organisms that lived in the area after the impact of the asteroid showed a significant amount of innovation in how they adapted to a very different new environment. This rapid recovery could also serve to remind us of the resiliency and durability of biological systems.

Timothy Bralower, professor of geological sciences at Penn State University and co-author of the study, commented on the speed of recovery, saying, “It is amazing to see complex life return to an area in such a geologic heartbeat.” He continued, “It may also encourage modern species that will withstand the impacts of human-induced habitat loss.”

The speed of recovery from the Chicxulub event did not mean that conditions were totally back to normal immediately. However, it demonstrates that recovery continued in this area for millions of years afterward and produced a transformation of marine ecosystem development and the origin of new plankton communities. Early recovery occurred earlier than had been previously thought.

Additionally, the results suggest that, while evolutionary rates may be slow under normal conditions, they can be transformed rapidly during extreme environmental changes, such as asteroid impacts and volcanism. This challenges the traditional view of how ecosystems recover from collapse. It also underscores the need for precise dating techniques when reconstructing Earth’s history.

The results of the present research change our view of recovery following mass extinctions. A shorter timeline for early diversification indicates that ecosystems can recover their complexity at a faster rate than was thought possible after a mass extinction event. The findings of this study will likewise improve predictive models of the evolution of biodiversity, ocean chemical recovery after global climatic disasters, and the overall resiliency of biological systems.

The results of the study will serve to illustrate that the use of alternative dating methods, such as helium-3, has significant potential as a way to overcome the limitations of traditional approaches to dating geological samples when they fail due to uncertainties. The research also provides a long-term perspective on the resilience of biological systems to adapt and evolve rapidly, even after they have undergone massive disruption. How this occurs, however, will always remain uncertain.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geology.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Marine life evolved rapidly after the dinosaur killing asteroid impact 66 million years ago appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.