Hours after ringing the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange on a Monday last December, Omeed Malik hosted a party at the Core Club in midtown Manhattan. He suggested I come along. “Just look decent,” he texted me, after I asked about a dress code. It was a relatively small gathering. Skyline views. A few New York Post reporters were making the rounds, as were producers for Tucker Carlson, whose post–Fox News career Malik was funding.

It was here that the financier wanted to tell me about his idea for a “parallel economy” — a kind of Brexit for conservatives from corporate America, which he saw tilting inexorably into wokeness. Malik’s answer to DEI, he told me, was his own acronym: EIG, or companies that prioritize entrepreneurship, innovation, and growth. “73 million people voted for Donald Trump, and the Brookings Institute quantifies that as 30 percent of American GDP,” he said — totaling roughly $7 trillion. “That’s the third-largest economy in the world. I’m happy to be the financier of the third-largest economy. I don’t need to go to Vietnam or India. I’m here.” As we were talking, though, I couldn’t stop looking at the orange horse-patterned scarf he wore around his dark suit. “Hermès,” he said. “And so is the tie. I guess that’s not necessarily a man-of-the-people look, but it looks good nonetheless.” (As for me, well, I tried.)

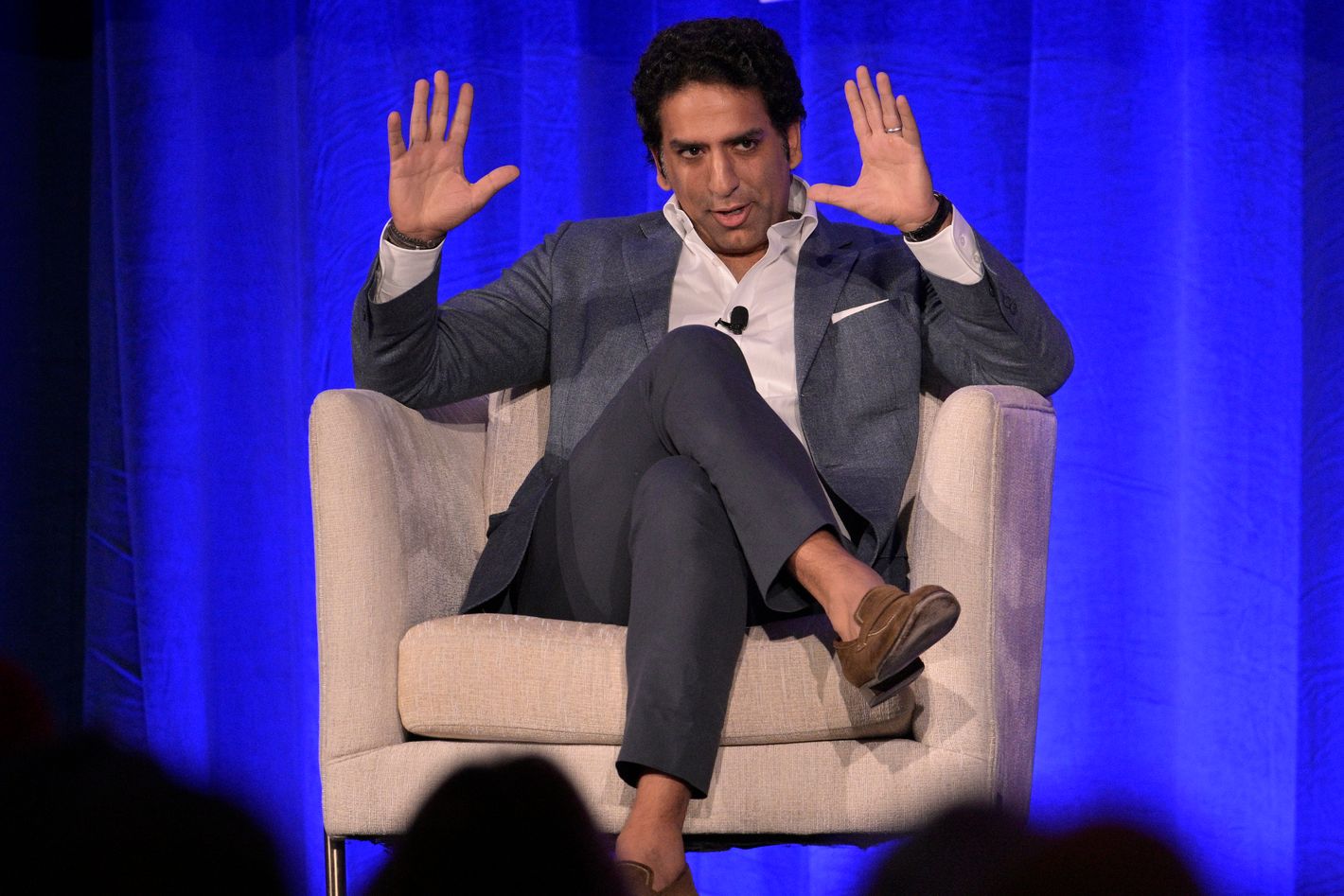

Nearly a year has passed, and it looks like Malik’s pitch is meeting its moment. Donald Trump’s second election win comes amid a massive corporate retrenchment: the scaling back of DEI, the lionization of anti-woke crusaders like Vivek Ramaswamy and Robbie Starbuck, and the end of the CEO as culture warrior. Malik was already one of the most quietly influential forces dismantling so-called woke capitalism. And now he’s Donald Trump Jr.’s new boss, after the president-elect’s oldest son — a close friend — joined his venture-capital firm, 1789 Capital, as a partner.

Woke capitalism is a messy term, but there’s no doubt that the last few years have been a strange time in corporate America. After the 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida, Wall Street banks stepped into the void left by lawmakers and limited business for gun sellers and manufacturers. Larry Fink, the CEO of private-equity giant BlackRock, wrote a letter that same year saying that corporations should not just look out for their shareholders, but make “a positive contribution to society,” and has sold financial products geared toward lofty environmental, sustainability, and governance (or ESG) goals. Diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, which challenged businesses to hire and promote women and minorities, proliferated.

The marriage between capital and social justice was sometimes comically awkward. (See: the same jokes every June about weapons manufacturers rolling out their Pride logos on social media.) But to the conservative side of Wall Street, this wasn’t just harmless posturing; it was a means of cutting off financing from businesses. “We looked at a deal with an apparel company — a big portion of this company’s customers are hunters,” Christopher Buskirk, a 1789 co-founder and chief investment officer, told me. “A fund had a deal to buy this company, but broke the deal because, they said, the fact that some of their customers wore the apparel while hunting violated their ESG agreement.”

Malik is quite possibly the poster boy for the post-cancellation conservative glow-up. Born in New Jersey to Iranian and Pakistani immigrants, he was, in his own telling, a “run-of-the-mill” Democrat until a few years ago. He wrote speeches for a Democratic congressman, Donald Payne Jr.; after law school, he went to work for Jon Corzine, the onetime Goldman Sachs partner and New Jersey governor, at commodities trading firm MF Global. (Soon after Malik joined, the company collapsed into bankruptcy.) Within a few years, Malik was running one of Bank of America’s most important businesses, its prime-services desk, a special brokerage service that caters to hedge funds. “He was the hotshot young Wall Street guy, and it was a business that Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs had had a lock on for 20 or 30 years,” one former client said. “He really put them on the map.”

On Wall Street, his vibe was decidedly pre–Great Financial Crisis. “With Omeed, it was back to the future,” said Scott Bessent, founder of the hedge fund Key Group, who is currently in the running to be the next Treasury secretary. “His companies are a modern model, but with an old-fashioned ethos.” He wore mirrored aviators, flaunted nice clothes, partied with beautiful women. He would eventually land a walk-on role on the Showtime series Billions. If you’d come across him at, say, Anthony Scaramucci’s SALT conference for hedge-fund managers, you’d find a man who had no second thoughts about enjoying his success.

Then, in 2018, he was fired. Allegations of “unwanted advances” toward a female banker were leaked to business reporters. Malik filed a defamation suit against Bank of America, denying that he had done anything wrong. He also filed a claim against the bank alleging that he was fired in retaliation after complaining that one of his bosses didn’t have the required securities licenses. (A markets watchdog later fined the bank over the issue.) Bank of America soon reportedly settled with him for eight figures, and he used some of that money to start his own investment bank, called Farvahar Partners. (He declined to comment on the settlement.) Other companies would follow: 1789 Capital, a venture-capital firm, would invest directly in companies. Colombier, a blank-check acquisition firm, would take them public through SPAC mergers.

Soon he was again connecting companies with money from investors, this time in private, as well as public, markets — a sign that his reputation wasn’t really affected by the news. “He does his work, and he understands the role that he’s meant to play. And if he presents that he can do something, he does it. I haven’t seen him fail when he says he’s going to do something,” one person familiar with his business around this time told me.

That night at the Core Club, Malik described to me how the pandemic had become a political breaking point for him. At the time, he was newly married and his wife was pregnant. Even though pregnant women were excluded from clinical COVID-vaccine trials, health officials still recommended they take the shots. He was against the prolonged lockdowns and vaccine mandates to re-enter public life. “That was when I said I’ve had it, and we moved to Florida,” he said.

Political-donation records show his break from Democrats started earlier, though. During the first half of 2019, almost all of Malik’s donations went to Democrats, including $2,800 each to Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg. By July, he had switched almost entirely to Republicans, including Donald Trump. By April 2020, he was contributing to Carlson’s conservative outlet the Daily Caller, and by August, he had invested in the site. It was around this time that Malik and Don Jr. first co-bylined an op-ed that was critical of China.

Malik and Don Jr. have been described as very close by three people familiar with their friendship — often traveling and hanging out together. But Malik, a Mar-a-Lago member, has also been quietly making inroads with some of MAGA world’s most important figures not named Trump. He has backing from Rebekah Mercer, the Republican mega-donor, while Blake Masters, the Peter Thiel protégé who has lost two bids for Congress in Arizona, sits on the board of 1789. He has donated to, and frequently interviewed, Tulsi Gabbard, the former Democrat. Malik was also described by one Trump adviser as part of J.D. Vance’s inner circle.

Malik was one of the biggest backers of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., raising millions of dollars for his third-party election campaign. But he remained close to the Trump family, according to two people directly familiar with his relationships. “He was day one,” one said. “There’s a group who just kept going after January 6, and he was part of that.” (Malik’s Instagram account on that day shows a video from the Capitol riots with the caption”I don’t care what side someone is on — violence is unacceptable in every situation,” but doesn’t mention Trump.) Two people told me he was involved in getting Kennedy and Gabbard to endorse Trump, and helped them get administration appointments: Gabbard as the director of national intelligence, and Kennedy to lead Health and Human Services.

But what good is a parallel economy when you’ve already won? 1789 has invested in companies like Substack, which has been a favorite of the conservative, non-elite media, as well as a pharmaceutical-delivery service that doesn’t seem obviously involved in any culture wars. Malik took the retail company Public Square, a kind of Amazon for conservatives, public last year through a SPAC, and he now sits on the board. Since its debut, however, the stock is down about 90 percent from its peak, and its last quarterly report showed it made $6.5 million in revenue — about what Amazon makes every ten minutes. (Malik holds a roughly 10 percent stake in the company and hasn’t sold any shares. He has been collecting a $60,000-a-month consulting fee from the company, two people familiar with the arrangement told me. One of them said that arrangement ended in November.) Meanwhile, Jeff Bezos has been trying to get in Trump’s good graces, and Amazon’s stock — the real thing, not the anti-woke version — is near all-time highs.

With wokeness on the retreat, it’s not clear whether Malik’s old playbook will be as relevant as it once was. But with his fortune and his deep connections to the incoming presidential administration, he probably isn’t too bothered by that. “When you’re the loyal opposition, maybe it’s okay to have ‘anti-’ in front of your name,” Malik said during a November 17 CNBC interview. “But I think we were validated in our thesis a couple of weeks ago.”